Abstract

The analysis of the utilization of mental healthcare services using routine data provided by statutory health insurance companies and pension funds is a way to assess the frequency of service use, the distribution of the service use among various healthcare settings (inpatients vs. outpatients, rehabilitation according mainly to the German Social Code Book IX vs. curative treatment according to the German Social Code Book V [note that some elements of rehabilitation are financed according to Social Code Book V as well]) and medical disciplines (psychiatry and psychosomatic medicine vs. somatic disciplines and general medicine). In addition, these data can provide information on the social consequences of mental disorders, as assessed by the number of cases and the duration of sick leave or case numbers of early retirement due to mental disorders. In this study, healthcare utilization data from 10 million Germans were analysed. Within a 3 year observation period (2005–2007), about one-third (approx. 3.3 million) persons had a contact with a healthcare service due to a diagnosis of the ICD-10 groups F0-F5. Given the large number of persons with depression in Germany, the initial results of an analysis of mental healthcare utilization due to depression are presented here. Among the study group of 3.3 million Germans with mental healthcare utilization within the observation period, 1.4 million had at least one contact to healthcare system due to the diagnosis of depression. In most cases, depression was diagnosed without specification of severity. It was found that non-psychiatric disciplines like general practitioners were the most frequently used providers in outpatient mental health care, whereas inpatient treatment predominantly occurred in psychiatric departments. For those persons with depression for which a severity-indicating ICD-10 code was used, it was found that utilization of psychiatric and psychosomatic disciplines increased in both in- and outpatient treatment compared to use of general medical facilities with more severe depression. Specialists for psychosomatic medicine and psychological psychotherapists predominantly treated cases of mild and moderate depression, whereas severe cases were mostly cared for by psychiatrists or psychiatric departments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The German mental healthcare system is characterized by a large variety of providers from different medical specialties divided between in- and outpatient services [3]. The utilization of healthcare services due to mental disorders in Germany has mainly been a subject for annual reports of health insurance companies. In general, these analyses showed an increased rate of mental disorders in healthcare utilization (e.g., [2]), although comprehensive reviews of this subject matter are still lacking. Federal governmental analyses also show increasing rates of hospital services utilization due to mental disorders. In spite of this high and increasing utilization rate, studies indicate considerable degrees of under treatment in European countries including Germany [1]. The main aim of this project was to analyze mental healthcare utilization in Germany in 2005–2007 by using secondary data from health insurance companies and the German Pension Funds (Deutsche Rentenversicherung-Bund, the major provider in Germany for rehabilitation and pension services, in our study for 70 % of the 3.3 million persons included in the analysis database) with a view to identify areas of potential optimization of mental health care by analyzing regional differences, utilization patterns considering different medical specialties and settings of care and by analyzing changes over time. To this end, for the first time, statutory health insurance data from three participating health insurance providers (DAK, hkk and KKH-Allianz) were combined in an anonymized analysis database with data provided by the German Pension Funds, which covers early retirement pensions due to health conditions and also rehabilitation services [4]. The population sample covered by these providers amounts to approximately ten million Germans, providing a unique opportunity to assess mental healthcare utilization over several years. So far, no study has assessed such a large number of persons across different service providers and on a nationwide basis. This is also the first analysis to combine health insurance and pension funds data, which provides an opportunity to analyze the pathways of care between all service providers involved in mental health care. Given the high number of persons with depression and other affective disorders in Germany [11], the first analyses presented here focus on affective disorders (group F3 of the International Classification of Disorders, 10th revision, ICD-10), especially depression (F32/F33). Analyzing depression also provides the only opportunity to assess the influence of disease severity on mental healthcare utilization, since only in the depressive disorders does the ICD-10 provide classification codes divided by degrees of disease severity. ICD-10 is the mandatory system for coding mental disorders in the German remuneration system used by service providers and health insurance companies.

Methods

Pseudonymized healthcare utilization data were obtained for those persons who were members of the before mentioned statutory health insurance companies in 2005–2007 and who had at least one contact with the healthcare system due to a diagnosis of the ICD-10 code groups F0-F5. The German Pension Funds data for these persons were obtained and combined in an analysis database, which was then completely anonymized. Provided here are the results of descriptive analyses of healthcare utilization frequencies in different settings and over the observation period of 3 years for persons with at least one diagnosis of depression during the observation period. Considered was the first depression diagnosis of each person during this time period (“index diagnosis”).

Results

Approximately 3.3 million persons covered by the three participating statutory health insurance companies had at least one contact with the healthcare system during 2005–2007. In the course of these 3 years, approximately 50 % of these had more than one mental disorder as assessed by ICD-10 F-codes [4].

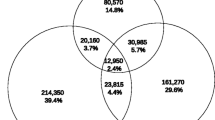

Among these 3.3 million persons with contact to the healthcare system due to a mental disorder, 1.4 million persons had at least one diagnosis of a depression (F32/F33) between 2005 and 2007 (n = 1,435,133; 43.8 % of all persons with contact to the healthcare system due to a mental disorder of the ICD-10 groups F0-F5). Figure 1 shows that the majority (approximately 73 %) of depression diagnoses ware classified as “unspecified” (F32.8/F32.9/F33.8/F33.9). In diagnoses with more specific depression coding, moderate and severe degrees of depression severity (F32.0-F32.3/F33.0-F33.3) prevailed. In 6 % of all persons with depression, the first depression diagnosis in the observation period (“index diagnosis”) was classified as a mild type (F32.0/F33.0); 13.5 % of all index diagnoses were of a moderate depression (F32.1/F33.1) and 7.7 % were diagnosed as severe (F32.2/F32.3./F33.2/F33.3).

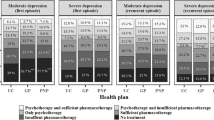

Figure 2 shows the relative utilization of different mental healthcare outpatient disciplines by persons with depression. The majority of persons with depression only utilizes general medical services (71.3 %). Thus, there is a clear predominance of general practitioners or providers of other somatic disciplines compared to the outpatient services provided by psychiatrists or specialists in psychosomatic medicine (note that psychosomatic medicine is a separate medical specialty in Germany and is not part of the medical specialty of psychiatry as in most other countries). General practitioners and specialists or other somatic specialties were the most frequently used service providers followed by psychiatrists (Fig. 3). The relative share of psychiatric services compared to other specialties increased with depression severity. Specialists for psychosomatic medicine and psychological psychotherapists only provided a minority of all contacts with the healthcare system for persons with depression (Fig. 3).

Outpatient treatment specified by disciplines. Database for analysis: all patients with outpatient treatment due to depression (ICD.-10 F32/F33) during the observation period (2005–2007) (N = 1,335,555 = 93 % of all patients with an index diagnosis of depression in 2005–2007). Light gray sector treatment only by general practitioners or other somatic medical specialists; medium gray sector treatment by general practitioners or other somatic medical specialists and psychiatrists, specialists in psychosomatic medicine or psychological psychotherapists (note that in Germany, psychosomatic medicine is a medical specialty separate from psychiatry). Black sector treatment only by psychiatrists, specialists in psychosomatic medicine or psychological psychotherapists

Outpatient treatment specified by disease severity and disciplines. Database for analysis: all patients with outpatient treatment due to mild, moderate and severe depression in the observation period 2005–2007 (contacts to different disciplines were possible). Left group mild depression (ICD-10 F32.0 and F33.0; n = 131.980). Middle group moderate depression (ICD-10 F32.1 and F33.1; n = 297.370). Right group severe depression (ICD-10 F32.2., F32.3, F33.2. and F33.3; n = 181.424). Black bars treatment by psychiatrist or child and adolescent psychiatrist. Light gray bars treatment by specialist for psychosomatic medicine. Dark gray bars treatment by psychological psychotherapist. White bars treatment by general practitioner or other somatic discipline

Regardless of depression severity, the analysis of inpatient treatment shows a dominant role of psychiatric departments in providing inpatient treatment of all degrees of severity in depression (Fig. 4). Similar to the situation in outpatient treatment, the relative share of specialized psychiatric departments among all inpatient healthcare service use increased with the degree of depression severity. Figure 4 shows that some treatment cases with a main diagnosis of a depression occur in somatic departments (5 % of cases of severe depression, 15 % of cases of mild depression).

Utilization of inpatient treatment due to mild, moderate or severe depression (defined by the main diagnosis of inpatient treatment) in inpatient departments of different disciplines. Database for analysis: all patients in inpatient treatment with a main diagnosis of mild depression (left group n = 1.078; ICD-10 F32.0 and F33.0), moderate (middle group n = 22.132; ICD-10 F32.1 and F33.1) or severe depression (right group n = 30.878; ICD-10 F32.2., F32.3., F33.2 and F33.3) in 2005–2007. Multiple cases per person were counted where appropriate (for persons with multiple admissions in different specialty departments). Bar 1 Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. Bar 2 Department of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy. Bar 3 Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Bar 4 Department of Addiction Medicine. Bar 5 Department of Neurology. Bar 6 Other somatic department

Discussion

These analyses show that depression is a very frequent disorder leading to mental healthcare utilization, in that 1.4 million of all 3.3 million persons utilizing mental healthcare services in 2005–2007 (from a total sample population of 10 million Germans) had a diagnosis of depression. These results support the findings from previous epidemiological and healthcare utilization studies [6–8, 11]. Further analyses showed that the pattern of service providers was different in the outpatient compared to the inpatient sector: While there was a predominance of general practitioners and specialists from other non-psychiatric specialties in the outpatient sector, inpatient treatment occured predominantly in specialized departments for psychiatry. This indicates that general practitioners and specialists from other non-psychiatric medical specialties play an important role in detecting and diagnosing depression in Germany. Both in the study presented here and in a report by the Federal Joint Committee on depression healthcare in Germany [5], the majority of affective disorders were shown to be classified as “unspecified,” and further studies are needed to clarify the reasons for this. The study by the Federal Joint Committee indicates that general practitioners mainly use the “unspecified” code. Medical school curricula and postgraduate teaching courses need to ascertain that general practitioners are competent in diagnosing and treating depression. A specialized curriculum for training general practitioners is currently being developed by the Departments of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (W. Gaebel) and the Department of General Medicine (S. Wilm, H.H. Abholz) of the medical faculty of the Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf.

Another aspect evident from the analysis is that the majority of cases of inpatient care of depression occured in specialized psychiatric departments. This was expected, but it was surprising to see that a considerable share of persons with a main diagnosis of depression were treated in inpatient departments of other medical specialties. Since the analysis was based on the main diagnosis for inpatient treatment, this may indicate a certain need of consultation services. However, further analyses are needed to reveal the pathways of care of those persons treated in somatic departments, in order to analyse in how far these persons were treated in psychiatric departments or by psychiatrists in private practices following the inpatient stay in a somatic department.

A final pattern of healthcare utilization became evident when disease severity was considered. The share of specialized inpatient or outpatient psychiatric services among all healthcare service utilization increased with increasing depression severity. While this reached nearly 90 % of all cases in the inpatient departments, the rate only reached 45 % in outpatient settings. This indicates that general practitioners and medical specialists of other somatic specialties provide services to approximately half of all severely depressed persons in Germany. Further analyses are currently underway to determine whether sick leave rates, rates of early retirement and mortality rates are different depending on the service types used. These figures also suggest that general practitioners not only need to be competent in detecting and treating depression in general, but also in cases of high severity. Therefore, detection and appropriate management of complex clinical situations like therapy refractoriness and suicidality clearly need to be included in the relevant education programs in medical schools or in continuing medical education.

A final point is the comparatively small share of specialists in psychosomatic medicine and of psychological psychotherapists, especially considering that the numbers of psychological psychotherapists in Germany by far exceeds the number of psychiatrists in private practices. Similar findings have been reported before [8, 10], and further analyses are needed to clarify the reasons for such a discrepancy between the numbers of service providers and their share of healthcare utilization.

In summary, these initial analyses show that depression is a major reason for mental healthcare utilization in Germany and that besides psychiatrists, general practitioners and other somatic medical specialists provide the majority of outpatient services, while the majority of inpatient services are provided by departments of psychiatry. Using secondary data is a powerful tool in healthcare utilization analyses to detect such patterns of utilization on a nationwide basis [9]. Although limitations as to the availability of such data for research projects are still considerable, the results presented here show that by combining data from several health insurance providers, large numbers of cases can be analyzed. Further studies are underway to analyze mental healthcare utilization caused by other mental disorders including data on rehabilitation treatment.

References

Alonso J, Codony M, Kovess V, Angermeyer MC, Katz SJ, Haro JM, De Girolamo G, De Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Vilagut G, Almansa J, Lépine JP, Brugha TS (2007) Population level of unmet need for mental healthcare in Europe. Br J Psychiatry 190:299–306

DAK-Unternehmen Leben (2010) DAK Gesundheitsreport 2010. Deutsche Angestelltenkrankenkasse, Hamburg. http://www.presse.dak.de/ps.nsf/Show/03AF73C39B7227B0C12576BF004C8490/$File/DAK_Gesundheitsreport_2010_2402.pdf. Last Access 19 August 2012

Gaebel W, Janssen B, Zielasek J (2009) Mental health quality, outcome measurement, and improvement in Germany. Curr Opin Psychiatry 22:636–642

Gaebel W, Zielasek J, Kowitz S, Fritze J (2011) Patienten mit Psychischen Störungen: Oft am Spezialisten vorbei. Dtsch Ärztebl 108(26):A-1476/B-1245/C-1241

Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss (2011) Modellprojekt Verfahren zur verbesserten Versorgungsorientierung am Beispielthema Depression. Federal Joint Committee. http://www.g-ba.de/downloads/17-98-3016/2011-02-17_Versorgungsorientierung_Bericht.pdf. Last Access 19 August 2012

Jacobi F, Klose M, Wittchen HU (2004) Psychische Störungen in der deutschen Allgemeinbevölkerung: Inanspruchnahme von Gesundheitsleistungen und Ausfalltage. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz 47:736–744

Kovess-Masfety V, Alonso J, Brugha TS, Angermeyer MC, Haro JM, Sevilla-Dedieu C, the ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Investigators (2000) Differences in lifetime use of services for mental health problems in six European countries. Psychiat Serv 58:213–220

Kruse J, Herzog W (2012) Zwischenbericht zum Gutachten “Zur ambulanten psychosomatischen/psychotherapeutischen Versorgung in der kassenärztlichen Versorgung in Deutschland—Formen der Versorgung und ihre Effizienz“. Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung. http://daris.kbv.de/daris/doccontent.dll?LibraryName=EXTDARIS^DMSSLAVE&SystemType=2&LogonId=01ba3fa667cc06c884ca1c6d0dadb3ac&DocId=003764910&Page=1. Last Access 19 August 2012

Mansky T, Robra BP, Schubert I (2012) Vorhandene Daten besser nutzen. Dtsch Arztebl 109:A1082–A1085

Melchinger H (2008) Ambulante psychiatrische Versorgung. Umsteuerung dringend geboten. Dtsch Arztebl 105:A2457–A2460

Wittchen HU, Jacobi F (2001) Die Versorgungssituation psychischer Störungen in Deutschland. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz 44:993–1000

Acknowledgments

This article is part of the supplement “Personalized Psychiatry and Psychotherapy”. This supplement was not sponsored by outside commercial interests. The study was supported by funds of the German Medical Association (Project 08-97) and the German Association of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (DGPPN). In addition, institutional funds provided by the LVR-Klinikum Düsseldorf were used to support this study. The authors thank the participating health insurance companies (KKH-Allianz, DAK and hkk), the association of health insurance companies (Verband der Ersatzkassen) and the German Pension Fund (Deutsche Rentenversicherung-Bund) for supporting this study and providing data for this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gaebel, W., Kowitz, S. & Zielasek, J. The DGPPN research project on mental healthcare utilization in Germany: inpatient and outpatient treatment of persons with depression by different disciplines. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 262 (Suppl 2), 51–55 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-012-0363-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-012-0363-2