Abstract

In this article, we will introduce interpersonal psychotherapy as an effective short-term treatment strategy in major depression. In IPT, a reciprocal relationship between interpersonal problems and depressive symptoms is regarded as important in the onset and as a maintaining factor of depressive disorders. Therefore, interpersonal problems are the main therapeutic targets of this approach. Four interpersonal problem areas are defined, which include interpersonal role disputes, role transitions, complicated bereavement, and interpersonal deficits. Patients are helped to break the interactions between depressive symptoms and their individual interpersonal difficulties. The goals are to achieve a reduction in depressive symptoms and an improvement in interpersonal functioning through improved communication, expression of affect, and proactive engagement with the current interpersonal network. The efficacy of this focused and structured psychotherapy in the treatment of acute unipolar major depressive disorder is summarized. This article outlines the background of interpersonal psychotherapy, the process of therapy, efficacy, and the expansion of the evidence base to different subgroups of depressed patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) was initially developed as a time-limited and manualized psychotherapeutic approach for the treatment of major depression in outpatients by Gerald Klerman and Myrna Weissman [7]. The initial goal was to create a comparable study condition to pharmacotherapy for use in clinical trials. After having shown success with depressed patients in a series of controlled comparative treatment trials, IPT manuals have been distributed since 1984, improved, and translated into different languages including German [12, 16, 17].

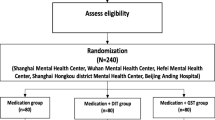

Concerning the theoretical background, IPT is based on Adolf Meyers’ “Psychobiological Approach” [9] as well as Harry Stack Sullivans’ “Interpersonal School” [15] and John Bowlbys’ “Attachment Theory” [1]. Thus, the main focus is the relationship between mood and interpersonal events. Results from various different research topics underline the importance of this relationship such as child development studies, animal studies, epidemiological studies, or research from the fields of “expressed emotion,” “social support,” or “life events.” For example, it has been shown that disturbing events and psychosocial stress may precipitate depression, whereas having confidants and other intimate relationships may function as protective factors against depression [8]. In IPT, the etiology of depressive disorder is assumed to be multifactorial (genetic and environmental), but to emerge always within the psychosocial and interpersonal context of the patient. A reciprocal relationship between interpersonal stress and depression in the onset as well as a maintaining factor is considered as the core issue to be targeted (compare Fig. 1). The IPT therapist should explicitly target the patient’s axis I mood disorder, as opposed to attempting character change targeting profound personality structures or childhood issues [8]. Thus, IPT is most efficiently used in acutely depressed patients experiencing psychosocial problems, communication problems, or partnership conflicts. Severe personality disorders are not contraindication, but could come along with a less favorable outcome. The IPT techniques are disorder specific, rather than strongly committing to one psychotherapeutic school.

Therapeutic relationship in IPT

To reach the goals defined above the therapist should follow a certain attitude. He should consider himself as the patient’s “advocate” that means he should not be a neutral therapist, but a friendly, helpful ally, who is actively acting in an encouraging, optimistic, and supportive manner. In contrast to other psychotherapeutic approaches, the therapist should avoid usage of transference interpretations or hypotheses as well as connecting too close in terms of a friendship. However, in specific situations, the therapist could use personal disclosure (e.g., telling the patient about one’s own divorce) to function as a role model. Overall, the therapist should stay in a complementary relationship formation, providing the opposite role to the patient’s behavior: If the patient appears passive and support seeking, this could imply acting active and supportive, providing orientation. If the patient’s attitude seems submissive and dependent, the therapist should grant autonomy and provide information. Meanwhile, the therapist will try to help the patient evaluate their current situation and master possible conflicts and problems, always staying focused and in a defined schedule.

Techniques and structure of IPT

Techniques used in IPT are, on the one hand, from different traditional schools including nondirective exploration and encouragement of expressing affects as well as direct elicitation and clarification of conflicts, communication analysis and decision analysis, role plays, and usage of the therapeutic relationship. On the other hand, the therapist uses IPT-specific strategies that are explained in the following sections.

Following the claim to be focused and structured, IPT is divided into three phases: The initial phase, the middle phase, and the termination phase. Klerman and Weissman proposed that one to three initial sessions are followed by nine intermediate contacts and completed by three final sessions. Sessions are generally scheduled weekly (or twice a week at the start of therapy) and will take 50–60 min each [8].

Initial sessions

The initial phase permits anamnesis and diagnosis. The patient should be relieved through diagnosis and psycho education following a medical model. Hope should be instilled. Also, the IPT therapist should explicitly inducts patients into the sick role, which means that patients are excused from usual social roles and obligations that their illness renders impossible, but substitutes the requirement that the patients work to recover their health [8]. Another important goal is to elicit the interpersonal inventory. Here, the therapist explores the important present and past relationships in the patient’s life. A useful worksheet to get an overview about the social network and to optimize this network (during the middle phase) is shown in Fig. 2. At the end of the interpersonal inventory, the question has to be answered what changes have occurred in key relationships preceding and during the depressive interval? This leads to the next goal of the initial phase, to establish the interpersonal problem area. The therapist decides together with the patient which of the four interpersonal problem areas best fits the patient’s situation. The initial phase ends with a written treatment contract containing the patient’s most relevant one or two IPT foci and 2–3 well-defined interpersonal goals within each IPT focus, which are realistically achievable during the treatment period. Also, general goals (concerning depressive symptoms) can be phrased. Finally, additional organizational aspects like the frequency of sessions and the duration of the treatment should be added.

Middle sessions

The main work on interpersonal and psychosocial stressors associated with depression takes place during the middle sessions. The therapist and patient focus on one or more of the four IPT problem areas; Klerman and Weissmann call this the heart of the treatment process [8]. The four IPT problem areas are: Interpersonal role dispute, role transition, complicated bereavement, and interpersonal deficits. Each one will be discussed separately below. The general approach in the middle phase is firstly, to explore the area of interest, secondly, to focus on the patient’s perceptions and expectations, and thirdly, to train new ways of coping and behavior.

Final sessions

Successful detaching and preparation for the time post-therapy is the focus of the termination phase. It appears to be important to discuss termination explicitly and in time. Therefore, it could be useful to acknowledge that termination could be a time of sadness—a role transition on its own. The therapist is demanded to strengthen the patient’s recognition of independent competence, assess the need for maintenance treatment, and deal with possible nonresponse. Here, one can try to minimize, for example, the patient’s self-blame by decreasing the level of importance of the actual treatment and emphasizing alternative treatment options.

Main foci

Interpersonal role dispute

One of the interpersonal problems patients with major depression frequently present with results from interpersonal role disputes (e.g., a struggle with a sexual partner, family member, roommate, or coworker). In IPT, disputes are defined by a situation in which the patient and an important person in the patient’s life have different expectations about their relationship. If this is the case, the therapist and the patient prove whether the dispute is open or tacit. After the conflict is identified, the therapist helps the patient to understand his or her role in the dispute, and the link between the conflict and the patient’s depressive symptoms. Then, the therapist encourages the patient to explore potential behavioral options in changing the relationship and the likely consequences of each option, followed by a plan of action which could include modifying expectations or misleading communication. Central issues in this process are establishing the patient’s wants and how he/she can best achieve it. Regarding IPT, even dissolution of the relationship can be a satisfactory solution if the interpersonal situation proves truly impassable and impossible.

IPT defines three states of dispute which require different approaches. If the two parties are in negotiation, the therapist will try to assuage the participants to facilitate a resolution. If there is an impasse, one can try to increase disharmony in order to reopen negotiation. In case a final dissolution of the relationship had already been reached, the therapeutic challenge would be to assist the mourning process.

At this level, role plays represent a useful tool to determine the stage of dispute and to help the patient’s understanding of how nonreciprocal role expectations relate to the dispute.

Role transition

The second most common focus is found in challenging or failed role transitions. Any major life event or a change in relationship structure can alter one of the patient’s roles. Examples for role transitions are the beginning or ending of any life situation like marriage or divorce, matriculation or graduation, hiring or firing, the diagnoses of a medical disease or the prescription of its cure [8]. These role transitions can lead to a depressive reaction, especially when accompanied by a loss of family support or close attachments, inadequate coping of associated emotions like anger, grief, and fear, or a decrease in self-esteem. Depressed patients in such role transitions do often harp on the disadvantages of the change rather than the opportunities it presents. The therapist’s first goals are to help the patient understand the role transition and the positive and negative ramifications. Therapists should facilitate mourning and acceptance of the loss of the former role as well as to help the patient regard the new role in a more positive light and to restore self-esteem. One useful tool is the compilation of a four-field scheme illustrating positive and negative aspects of both roles. Fields to explore are the patient’s feelings about the loss, about the change itself, and about opportunities of the new role. Realistic evaluation of the loss, appropriate release of affect, and the development of a (new) social support system and skills called for in the new role are encouraged. When confronted with role transitions, patients can often be observed to exaggerate assets and diminish drawbacks of the former role while diminishing assets and exaggerating drawbacks of the new one.

Complicated bereavement

Another challenging topic is coping with severe grief or complicated bereavement. For the purpose of IPT, grief is narrowly defined as the reaction to the death of a significant other. Other losses (like jobs or divorces) are categorized as role transitions in IPT. It is important to distinguish between the uncomplicated, “normal” bereavement which is not a psychiatric disorder and the complicated pathological bereavement. In the “normal” grieving process involving depression-like symptoms as immediate reaction to the loss, the severity of these symptoms gradually decreases over time dependent on the availability of social support. In depressed patients suffering from complicated bereavement, the grieving process sometimes does not become apparent until long after the actual loss and can manifest itself in various ways. Instead of a depression-like reaction, patients can develop physical symptoms or, in case someone close to the patient died of an illness, become convinced that they are affected by the same illness. Severe complicated grief is referred to as a long lasting period with severe symptoms, for example, excessive guilt or suicidal ideation. Therapeutic strategies can implement facilitating the mourning process (catharsis) and helping the patient reestablish interests and relationships that can substitute for the loss. Further helpful approaches, for example, cover the reconstruction of the patient’s relationship with the deceased, describing the sequence and consequences of events just prior to, during, and after the death or exploring associated feelings (negative as well as positive ones). Emotional release should, as a crucial component of the grieving process, be encouraged by the therapist.

After recognizing a reduced effectiveness in fighting grief symptoms compared with depressive ones, modifications have been made to adjust IPT to specific severe grief treatment (complicated grief treatment) [14].

Interpersonal deficits

If none of the other three interpersonal problem areas fits, the last interpersonal problem area is called interpersonal deficits. In this rubric, patients have not experienced any acute major life event but rather suffer from loneliness, social isolation, and boredom. They have a paucity of intimate or supportive interpersonal relationships. Therapeutic goals are here to reduce the patient’s social isolation and to encourage the formation of new relationships. The strategies include reviewing past significant relationships with their negative and positive aspects and exploring repetitive patterns in relationships. Also, the discussion of the patient’s positive and negative feelings about the therapist, and encouraging the patient to identify parallels in other relationships may be helpful. An extensive use of role plays and communication analysis can help to develop and train social skills. This IPT problem area has been less used, least studied, and least conceptually developed. It seems to be a residual category for patients whose interpersonal difficulties may indicate a chronic course of depression and comorbid personality disorders. Prognosis is worse. In this context, IPT seeks to initiate an improvement process rather than reach a perfect solution. The cognitive analysis system of psychotherapy (CBASP) specifically developed for such chronic cases seems to be the more effective treatment for this patient group [13].

Efficacy

Over the past three decades, the efficacy of the IPT approach has been confirmed. The response rates have been compared with other psychotherapies, placebo, and medication [4, 6], and follow-up relapse rates have been examined [11]. A recent meta-analysis [2] concluded that IPT efficaciously treats depression, both as an independent treatment and in combination with pharmacotherapy. The authors summarized that IPT deserves its place in treatment guidelines [3, 10] as one of the most empirically validated treatments for depression [2].

In addition to outpatient usage, IPT was incorporated into an intensive multidisciplinary inpatient concept. Adaptations include additional support from nursing staff, access to IPT-group therapies, and more frequent contact with the therapist. IPT in this inpatient modification has proven short- and long-term efficacy [11].

Concerning outpatients, the additional use of booster sessions on a regular basis has been shown to significantly decrease the frequency of depressive episodes [5].

Conclusion and future prospects

Interpersonal psychotherapy has proven its efficacy both as a form of acute treatment and also as a maintenance treatment in major depressive in and out patients. Thus, IPT earned its place as a psychotherapeutic method and is approved for the use and teaching of psychiatric residents as well as psychological therapist trainees. Meanwhile, there are well-organized pathways of becoming a certificated interpersonal therapist, a schedule which includes theoretical and supervised practical training. Further research may specify indications for the use of IPT in contrast to other antidepressant psychotherapies and should focus on process research to optimize the strategies.

References

Ainsworth MDS, Bowlby J (1991) An ethological approach to personality development. Am Psychol 46:331–341

Cuijpers P, Geraedts AS, van Oppen P, Markowitz JC, van Straten A (2011) Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 168(6):581–592

DGPPN, BÄK, KBV, AWMF, AkdÄ, BPtK, BApK, DAGSHG, DEGAM, DGPM, DGPs, DGRW (Hrsg) für die Leitliniengruppe Unipolare Depression (2009) S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression—Langfassung, 1. Auflage. DGPPN, ÄZQ, AWMF, Berlin, Düsseldorf

Elkin I, Shea T, Watkins JT, Imber ST, Sotsky SM, Collins JF, Glass DR, Pilkonis PA, Leber WR, Docherty JP, Fiester SJ, Parloff MB (1989) National institute of mental health treatment of depression collaborative research program general effectiveness of treatments. Arch Gen Psychiatry 46:971–982

Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Wagner EF, McEachran AB, Cornes C (1991) Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy as a maintenance treatment of recurrent depression contributing factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48:1053–1059

Hollon SD, Jarrett RB, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Trivedi M, Rush AJ (2005) Psychotherapy and medication in the treatment of adult and geriatric depression: which monotherapy or combined treatment? J Clin Psychiatry 66:455–468

Klerman GL, Weissman M, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES (1984) Interpersonal psychotherapy of depression. Basic Books, New York

Markowitz JC, Weissman MM (1995) Interpersonal psychotherapy. In: Beckham EE, Leber WR (eds) Handbook of depression 2nd ed. The Guildford Press, New York, pp 376-390

Meyer A (1957) Psychobiology. Springfield, Illinois, Charles C Thomas

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance (2010) Depression: the treatment and management of depression in adults (updated edition). British Psychological Society, Leicester (UK)

Schramm E, van Calker D, Dykierek P, Lieb K, Kech S, Zobel I, Leonhart R, Berger M (2007) An intensive treatment program of interpersonal psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy for depressed inpatients: acute and long-term results. Am J Psychiatry 164:768–777

Schramm E (2010) Interpersonelle Psychotherapie. Mit dem Original-Therapiemanual von Klerman, Weissman, Rounsaville und Chevron. 3. Auflage. Schattauer GmbH, Stuttgart

Schramm E, Zobel I, Dykierek P, Kech S, Brakemeier EL, Külz A, Berger M (2011) Cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy versus interpersonal psychotherapy for early-onset chronic depression: a randomized pilot study. J Affect Disord 129:109–116

Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, Reynolds CF 3rd (2005) Treatment of complicated grief: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 293:2601–2608

Sullivan HS (1953) The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. Norton, New York

Weissman MM, Markowitz JC, Klerman GL (2007) Clinician’s quick guide to interpersonal psychotherapy. Oxford University Press, New York

Weissman M, Markowitz J, Klerman G (deutsche Einleitung und Herausgabe von A. Maercker) (2009) Interpersonelle Psychotherapie. Ein Behandlungsleitfaden. Hogrefe, Göttingen

Acknowledgments

This article is part of the supplement “Personalized Psychiatry and Psychotherapy.” This supplement was not sponsored by outside commercial interests. It was funded by the German Association for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (DGPPN).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brakemeier, EL., Frase, L. Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) in major depressive disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 262 (Suppl 2), 117–121 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-012-0357-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-012-0357-0