Abstract

The aims of this study were to analyze the presence of gender differences in the phenotypic expression of schizophrenia at the onset of illness and to explore whether these differences determine clinical and functional outcome 2 years after the initiation of treatment. Data from 231 first-episode-psychosis non-substance-dependent patients (156 men and 75 women) participating in a large-scale naturalistic open-label trial with risperidone were recorded at inclusion and months 1, 6, 12, and 24. Men presented a significant earlier age of onset (24.89 years vs. 29.01 years in women), poorer premorbid functioning, and a higher presence of prodromal and baseline negative symptoms. Women were more frequently married or lived with their partner and children and more frequently presented acute stress during the year previous to onset than men. No other significant clinical or functional differences were detected at baseline. The mean dose of antipsychotic treatment was similar for both genders during the study, and no significant differences in UKU scores were found. The number of hospitalizations was similar between groups, and adherence was more frequent among women. At the 2-year follow-up, both groups obtained significant improvements in outcome measures: PANSS, CGI severity, and GAF scores. Significant gender * time interactions were detected for negative and general PANSS subscales, with the improvement being more pronounced for men. However, no differences were detected for the mean scores obtained during the study in any outcome measure, and the final profile was similar for men and women. Our results suggest that although the initial presentation of schizophrenia can differ according to gender, these differences are not sufficient enough to determine differentiated outcome 2 years after the initiation of treatment in non-substance-dependent patients. The influence of gender on the early course of schizophrenia does not seem to be clinically or functionally decisive in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gender has been considered to be one of the factors that contribute to the heterogeneity of psychotic disorders. Murray et al. (1985) suggested the possibility of “female psychosis” versus “male psychosis”, pointing out not the existence of two clinical subtypes of the illness, but underlying differences in the expression of clinical variables depending on the gender of the patient [53]. Accordingly, many authors support the notion that gender modifies the phenotypic expression of schizophrenia and underline the subsequent prognostic and therapeutic implications of these differences [6, 15, 16, 28, 38, 39, 48, 51, 61, 63, 64, 66, 71].

Male gender has been associated with higher prevalence and incidence of schizophrenia [14, 30], earlier age of onset, worse social premorbid adjustment, poorer social networks (patients are frequently unemployed and live alone), and more severe negative symptoms at onset [21, 31, 39, 42]. In contrast, estrogens are believed to have a protective effect against the development of illness. Consequently, women become ill later in life than men, with the most noticeable symptoms observed during the menopause [31, 32, 38]. Women are reported to present more affective symptoms and a better course and outcome characterized with a shorter duration of the acute phase of the illness, a lower and shorter rehospitalization rate, and a longer time to relapse [16, 38, 39, 59].

Unfortunately, there is no real consensus on gender-related differences; some authors do not support a higher incidence of schizophrenia in men [27, 30, 33] or differences in the age of onset [39, 63], and others have failed to find significant differences in the clinical expression of symptoms or disease course [1, 6, 8, 29, 31, 37, 45, 52, 65].

As for medication, women have been reported to respond significantly better to treatment after diagnosis [62]. This faster and better response is probably due to a potentially protective antidopaminergic effect of estrogens in relation to antipsychotic drugs [67] and to an increased self-awareness apparently derived from a better adequacy of introspection in women [9, 40]. Additionally, general recommendations for antipsychotic drugs prescription stress that most females require lower doses to repair symptoms and well-being [60]. Some authors have tried to analyze gender differences in the antipsychotic dose necessary for stabilization; however, findings on pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics are inconsistent. Whereas some studies have found that women need a 20% lower dose to control symptoms [7, 54], others have reported no gender differences [56, 62] or even higher doses in women [39]. Reaction to medication also seems to vary with gender. Differences in the severity of extrapyramidal symptoms and adverse effects have not been consistently studied, but some adverse effects (e.g., weight gain, hyperprolactinemia, and cardiac effects) are reported to be particularly problematic for women [2].

Although relevant prognostic factors in patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) have been widely analyzed, few studies have acknowledged gender as a key factor in the early course and outcome of these patients [16, 39, 48, 62]. Furthermore, even though published data suggest the existence of gender-associated differences in the clinical presentation of schizophrenia, treatment response, and outcome, results are inconclusive and to some extent contradictory [43]. Our limited knowledge of gender differences in FEP may be the result of methodological inconsistencies across studies—due mainly to the definition of the sample assessed (some studies include patients with both affective and non-affective psychosis, whereas others include only patients with schizophrenia; some studies include substance dependence as a criteria for exclusion, whereas others do not) and of variability in the types of antipsychotics prescribed. The aims of this study were to determine gender differences in phenotypic expression in non-substance-dependent patients (except tobacco) with a first episode of schizophrenia/schizophreniform disorder (FEsz/szform) treated with risperidone and to analyze possible gender differences in early course.

Methods

Study setting and recruitment

Data were collected as part of a large-scale 2-year multicenter naturalistic observational open-label trial with risperidone based on a flexible protocol of low doses up to a maximum tolerated dose within the range recommended in the summary of product characteristics. The aims of the original multicentre trail were as follows: (a) to assess the course of FEP and identify the presence of possible prognostic factors; and (b) to determine the efficacy and safety of oral risperidone in treating the disease. From the original sample (n = 436), only patients with a diagnosis of FEsz/szform confirmed at 6 months of follow-up according to DSM-IV criteria [5] were included in the present analysis (n = 231). The study was conducted from January 1998 to December 2001 at 7 spanish university hospitals with experience in the treatment of FEP. Patients recruited were either inpatients treated at these facilities or outpatients referred from their corresponding local mental health services. Participants did not obtain any payment for their participation. Consistent clinical care was provided—as normally delivered—to those patients who refused to participate in the study.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all the participating hospitals. The protocol was designed according to the guidelines of the Spanish Medications Agency.

Participants

Patients were included if they met the following criteria: (i) age between 15 and 65 years; (ii) presence of positive symptoms within FEP; (iii) no previous antipsychotic medication; (iv) suitability for treatment with oral risperidone. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) presence of a concomitant Axis I disorder; (ii) presence of a neurological or medically relevant condition; (iii) history of head trauma with loss of consciousness; (iv) current diagnosis of substance dependence (except tobacco); (v) treatment with antipsychotic medication for more than 2 weeks before the initiation of oral risperidone. All participants understood the nature of the study and gave their written informed consent before enrollment.

Data collection

Visits were at baseline and at months 1, 6, 12, and 24. Every interview lasted approximately 45 min, with the exception of the baseline and month 6 visits that lasted 120 min—divided in two separate sessions—mainly due to the diagnostic assessments. Clinical interviews and assessments were performed by experienced psychiatrists. The intra-class correlations (ICC) on clinical scales ranked from 0.87 to 0.96. Socio-demographic, family, and developmental data were collected from the patient’s medical records and interviews with patients and their relatives whenever possible. The presence of obstetric complications (OC) was assessed using the Lewis–Murray scale [44]. FEP, defined as the first time the patient came for treatment for a psychotic disorder, was diagnosed at baseline according to DSM-IV criteria using the Structured Clinical Interview-I (SCID I) [20]. This same interview was re-conducted at 6 months to determine and confirm specific psychotic diagnoses. The presence and severity of psychotic symptoms were evaluated using the Spanish version of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [55]. Other clinical scales used were the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) [34], the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) [72], the severity subscale of the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI) [25], the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) [19], and the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS) [10]. Data related to the presence of prodromal symptoms and date of onset of psychosis were collected by means of a semi-structured interview according to the models of Haffner et al. [31] and Larsen et al. [42] with the patient and a close relative familiar with the patient’s early course whenever possible. Prodromal symptoms were defined as follows: attenuated positive, negative, or disorganized with no significant clinical relevance for a psychiatric diagnosis; or sufficiently intense symptoms that were present for a period lower than or equal to 1 week. Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) was calculated as the number of months between the first psychotic symptom (DSM-IV criteria: delusions, hallucinations, formal thought disorder, and strange behavior with relevant severity and a duration of at least 1 week) and the date of initiation of appropriate antipsychotic treatment, which was implemented immediately after enrollment. Psychosocial stress was assessed using the DSM-III-R psychosocial stress axis. Premorbid IQ was estimated using the Information subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Revised (WAIS-R) [70]. This subtest was administered by clinical psychologists (ICC range = 0.97–0.99).

Treatment

All patients received oral risperidone after being diagnosed with an FEP. Treatment was based on a flexible protocol of low doses up to a maximum tolerated dose within the range recommended in the summary of product characteristics. Drugs other than risperidone were permitted according to the clinician’s judgment (e.g., benzodiazepines, mood stabilizers, and/or antiparkinsonian treatments). Tolerance was assessed using a self-reported questionnaire on adverse reactions to medication and the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale (UKU) [46]. In addition, patients were invited to participate in a variety of non-pharmacological therapies (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy, individual psychotherapy, and group therapy or family interventions).

Statistical analyses

Data are summarized using standard descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and frequency). All variables were checked for skewed distributions and outliers. For pre-onset and socio-demographic data, baseline clinical scores, and treatment measures, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare means for continuous variables. The chi-square test was used for the comparison of categorical measurements. Course of illness was assessed using a general linear model for repeated measures with time as the intra-group factor with 5 levels (baseline and months 1, 6, 12, and 24) and gender as the between-groups variable.

Results

Men accounted for two-thirds of the sample: 67.5% (n = 156) men versus 32.5% (n = 75) women. Participation rates were 77% at 1 year of follow-up and 60% at 2 years of follow-up. At the final visit, 61% (n = 95) of men and 60% (n = 44) of women were assessed. The men-to-women ratio (3:1) remained stable throughout the study. At year 2, data on age, gender, and baseline PANSS in the remaining group did not differ significantly from those of the dropout group. The main identified reasons for dropout were as follows: voluntary withdrawn of the trial 48%, restricted collaboration of the patient and/or poor compliance with the treatment 15%, intolerance 6.5%, lack of clinical response 6.5%, hospitalization 9%, and others (change of residence and different combinations of previous reasons) 15%. For this subsample, the psychiatrist’s judgement of the clinical state of the patient recorded at the last assessment completed was worse 2%, slightly worse 4.5%, equal 4.5%, slightly better 13%, better 35%, and much better 41%.

Socio-demographic and pre-onset clinical variables

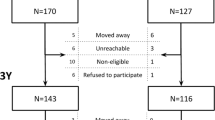

Socio-demographic and pre-onset clinical variables for each group are shown in Table 1. Age of onset according to family history of psychiatric disorders and of OC in men and women is represented graphically in Fig. 1.

Age of onset according to family history of psychiatric disorders and obstetric complications in men and women with a first episode of schizophrenia/schizophreniform disorder. Data are described as mean age (number of patients in the group). FH Family history of psychiatric disorders, positive (FH+) and negative (FH−); OC Obstetric complications, presence (OC+) and absence (OC−). a Significant differences F (1) = 6.437, P = 0.013; b Significant differences F (1) = 5.947, P = 0.016; c Significant differences F (1) = 8.932, P = 0.003; d Non-significant differences F (1) = 3.114, P = 0.082

Diagnostic distribution

Specific diagnoses confirmed at the 6-month follow-up are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences in the distribution by gender: χ² (6) = 10.039, P = 0.262.

Baseline symptoms

Baseline clinical data for the PANSS, CGI severity, and GAF scales are shown in Table 3. Men scored significantly higher than women on the PANSS negative subscale. No between-group differences were detected for depressive symptoms [HDRS men/women (mean ± SD) 15.52 ± 8.64/16.89 ± 9.79; F (1) = 0.969, P = 0.326] or mania [YMRS men/women (mean ± SD) 16.88 ± 7.83/15.20 ± 7.01; F (1) = 0.618, P = 0.435].

Disease course

Symptoms and functionality improved significantly over time (Table 3). The influence of gender on disease course was detected in relation to the PANSS negative and general subscales, in which the rate of change was significantly higher for men (Fig. 2). No significant differences were detected between groups for the mean score obtained during the study period for any clinical or functional variable assessed. The number of hospitalizations during the 2 years of the study was similar for men and women [men/women (mean ± SD, range) 0.82 ± 1.38, 0–10/0.68 ± 0.95, 0–4; Z = 0.522, P = 0.398]. No between-group differences were detected at the 2-year follow-up for depressive symptoms [HDRS men/women (mean ± SD) 5.79 ± 4.84/5.19 ± 5.50; F (1) = 0.188, P = 0.666] or mania [YMRS men/women (mean ± SD) 3.99 ± 5.66/3.06 ± 5.79; F (1) = 0.652, P = 0.421].

Treatment

At inclusion, 54% (n = 84) of men and 61% (n = 46) of women were enrolled in one of the different non-pharmacological treatments offered, with no significant differences in the distribution (χ² (1) = 1.154, P = 0.322). Antipsychotic treatment-related variables are presented in Table 4. No differences between groups were found concerning the percentage of patients that presented at least one extrapyramidal symptom during the study: 25% of men (n = 39) and 32% of women (n = 24), χ² (1) = 1.251, P = 0.273.

Discussion

The principal finding of this study was that, although there were gender differences in the phenotypic expression of schizophrenia in non-substance-dependent patients, the clinical and functional outcome 2 years after the first contact with the psychiatric service was similar for men and women. Therefore, our results do not support gender as a determinant prognostic factor during the early course of the disease in this population.

Gender differences at the onset of illness

Differences in phenotypic expression were detected in: (a) the incidence of cases among groups, (b) pre-onset clinical variables and socio-demographic characteristics at onset, and (c) initial psychopathological presentation.

Incidence of schizophrenia and gender

In our sample (231 patients with FEsz/szform, age 15–65 years), males were over-represented (67.5% vs. 32.5%). This predominance (3:1) is consistent with the ratios reported in previous studies including patients with a similar age of onset [39: Willhite 2008 #6203, 58, 71]. This result might support the hypothesis that incidence is higher in males [11, 35, 37]. However, Hafner et al. [31] suggested that the lifetime risk for schizophrenia is equal for males and females. This proposal is based on the antipsychotic effect of estrogens on dopamine D2 receptors, and therefore, in a proportion of women, the disorder only would become apparent after menopause [61].

Considering that the present study has an artificial age cutoff at 65 years with the result that very late onset (VLO) schizophrenia has not been included and women would be over-represented in a VLO group [38], we cannot conclude a real higher incidence of schizophrenia in males.

Pre-onset clinical variables and socio-demographic characteristics at onset

Women were more frequently married and living with their partner and children than men. This result may be associated—among other socio-cultural factors—with their better premorbid adjustment [57], lower number of prodromal symptoms than men, and later age of onset. Onset of illness occurred approximately 4 years later in women. This result is consistent with one of the most replicated findings in this area, namely, 2- to 5-year earlier age of onset of schizophrenia in males [13, 30, 32, 50]. Both a positive family history of psychiatric disorders and presence of OC have been related to earlier age of onset [3, 36, 68]. Accordingly, Fig. 1 shows a tendency for younger ages of onset in both males and females when considering these two variables. Differences in age of onset between genders disappeared only when comparing patients with a past history of OC. For females, this was the group with an earlier age of onset, and as suggested by Gureje et al. [24], the presence of OC accompanied with an earlier age of onset probably does of this subgroup of women the one with a poorer course and outcome. However, this result may be interpreted cautiously as the small sample size for women with OC (n = 18) could explain the lack of significant gender differences.

Initial psychopathological presentation

Consistent with the results of previous studies, men with FEsz/szform presented higher levels of negative symptoms than women at baseline [16, 38, 39, 63, 71]. This is not surprising if we consider that men more frequently presented prodromal symptoms classified in the negative dimension (social isolation, deterioration in personal hygiene, and lack of initiative) and poorer premorbid adjustment. Indeed, the association between poorer premorbid adjustment and higher levels of negative symptoms has been outlined [26, 52, 57, 63]. In the case of women, previous studies have reported that this group exhibit more affective symptoms than men [4, 16, 22, 23, 39, 49, 62]. Although women more frequently presented acute stress during the previous year than men, no differences were detected at baseline in mania or depressive symptoms. In our opinion, this discrepancy with previous results could be related to differences in the definition of the samples included across studies. Whereas our sample had homogeneous symptoms of schizophrenia, some previous studies have included affective psychosis or schizoaffective disorders that may have led to the differences reported [39, 47, 69]. This effect of heterogeneity in diagnosis was observed in the study by Cotton et al. [16], in which depressive symptoms are more frequent in women with an FEP. However, when only non-affective psychoses (schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder) in the total sample were taken into consideration, gender differences in depressive symptoms were no longer detected. In our sample, males and females did not differ in disease severity and social functioning at entry. Once again, this finding agrees with the results of Cotton et al., in which differences disappeared when only FEsz/szform patients were compared, despite the fact that gender differences in CGI severity or GAF scores were detected for the total sample of FEP patients.

Course and outcome of illness

Initiation of appropriate treatment helped both genders after 2 years. As expected, clinical symptoms and social functioning improved significantly in all patients, although there were no significant differences in the mean scores obtained during the study for PANSS subscales, CGI severity, or GAF. Progress was also similar between men and women, with the exception of the PANSS negative and general subscales, for which men displayed a more pronounced improvement during the first year. The more marked improvement in negative symptoms for men, who presented higher scores at baseline, meant that their final score was similar to that of women. Therefore, a higher score on negative symptoms at onset does not necessarily imply a worse outcome in non-substance-dependent male patients. We did not detect gender differences in the number of hospitalizations. Although the literature indicates than men have more hospitalizations and longer stays than women [66], not all studies have replicated this finding [6]. We consider that the clinical profile of the patients assessed as non-substance dependents may result in a lower number of inpatient admissions in men than that in studies including substance-dependent FEP patients [41]. The wider range in the number of hospitalizations observed in men may be probably due to gender-associated differences in social behaviors between men and women, for which men usually present more aggressive behaviors that might require hospitalization [66].

Antipsychotic treatment

No significant gender differences were detected in the dose of antipsychotic prescribed, either at baseline or at the 2-year follow-up visit. Although some authors report that women need a lower dose [7, 54], other authors have found similar doses for men and women [56, 62]. This discrepancy may be related to the differences in body mass index between groups and/or type of antipsychotic prescribed. For example, cigarette smoking is significantly higher in men and has been reported to increase the metabolism of some antipsychotic drugs [12, 18]. In the present study, the relevant factors mediating variability in the doses prescribed are dissipated, as there were no differences in BMI between the groups and all participants were receiving an antipsychotic whose metabolism is not altered by smoking [17].

There were no significant gender differences between the scores obtained for the UKU scale at the different assessment points. This result is consistent with the conclusion of a meta-analysis rebutting gender differences for any of the second-generation antipsychotics with respect to a higher rate of extrapyramidal symptoms, acute dystonia, or other movement disturbance [2]. A later study on gender differences in response to antipsychotic treatment confirms no differences in response to risperidone [67]. Adherence to treatment was significantly better in women throughout the study. This is an unexpected finding, as both genders presented similar symptoms and functioning at the follow-up visit. Nevertheless, this finding has been previously reported [16].

Strengths and limitations of the study design

This paper should be interpreted in light of its methodology. The study has significant strengths, including the offer of participation to all consecutively detected FEP cases (both in/outpatients) in a wide and representative geographical catchment area, covering the principal rural, urban, and metropolitan regions of Spain. Additionally, the homogeneity of diagnosis and antipsychotic treatment in the present study is an important methodological strength that avoids confounders arising from the inclusion of different diagnoses (e.g., affective psychoses) and treatments (e.g., differential protective influence of estrogens to specific antipsychotics and clinical response). However, relevant limitations should be also considered. Firstly, we acknowledge that constituting a clinical trial, the principal aim of the study might interfere in the representativeness of the sample recruited, for example including patients willing to start the antipsychotic treatment. Therefore, it might be impute that it constitutes a selected sample in which an epidemiological variable like gender cannot be thoroughly analyzed. However, the recruitment of patients was carried out in a naturalistic way, and the ratio 3:1 obtained in our sample is similar to the one reported in other epidemiological studies [16, 39, 63]. Secondly, it should be considered the clinical profile of the patients included, non-substance-dependent FEP patients. Persistent substance use, being more prevalent in males with a FEP, results in a reduction in illness insight, increases medication and treatment non-adherence and service disengagements, and results in a greater number of inpatient admissions and poorer longer-term outcome in FEP [16, 39]. Under our judgement, this factor may be probably—among others—at the basis of our results indicating a lack of differences among men and women in the early course and outcome of the illness and indirectly stress the clinical consequences of substance dependence for men. Finally, another limitation is the lack of data on history of substance use, a factor that has been shown to be relevant when considering gender differences [16, 39].

Conclusion

The results of the present study indicate that, although significant gender differences may be observed in the phenotypic expression of schizophrenia at the first episode, clinical differences are attenuated during the early course. This may be a result, among other factors, to the exclusion of substance-dependent patients, more frequently being men with a poorer prognosis than non-dependent patients. Our results indicate that gender alone may not constitute a specific prognostic factor during the early course of schizophrenia and indirectly stress the clinical consequences of substance dependence for men and the relevance of appropriated therapeutic interventions. Further research should consider the possibility of identifying specific prognostic factors associated with men and women independently to detect patients at risk of an unfavorable outcome.

References

Addington D, Addington J, Patten S (1996) Gender and affect in schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 41(5):265–268

Aichhorn W, Whitworth AB, Weiss EM, Marksteiner J (2006) Second-generation antipsychotics: is there evidence for sex differences in pharmacokinetic and adverse effect profiles? Drug Saf 29(7):587–598

Alda M, Ahrens B, Lit W, Dvorakova M, Labelle A, Zvolsky P, Jones B (1996) Age of onset in familial and sporadic schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 93(6):447–450

Altamura AC, Bassetti R, Bignotti S, Pioli R, Mundo E (2003) Clinical variables related to suicide attempts in schizophrenic patients: a retrospective study. Schizophr Res 60(1):47–55

American Psychiatric Association (1994) A diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4 edn. APA, Washington DC

Angermeyer MC, Kuhn L, Goldstein JM (1990) Gender and the course of schizophrenia: differences in treated outcomes. Schizophr Bull 16(2):293–307

Baldessarini RJ, Viguera AC (1995) Neuroleptic withdrawal in schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52(3):189–192

Biehl H, Maurer K, Schubart C, Krumm B, Jung E (1986) Prediction of outcome and utilization of medical services in a prospective study of first onset schizophrenics. Results of a prospective 5-year follow-up study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci 236(3):139–147

Brabban A, Tai S, Turkington D (2009) Predictors of outcome in brief cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 35(5):859–864

Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Wyatt RJ (1982) Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 8(3):470–484

Cannon TD, Kaprio J, Lonnqvist J, Huttunen M, Koskenvuo M (1998) The genetic epidemiology of schizophrenia in a Finnish twin cohort. A population-based modeling study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55(1):67–74

Carrillo JA, Herraiz AG, Ramos SI, Gervasini G, Vizcaino S, Benitez J (2003) Role of the smoking-induced cytochrome P450 (CYP)1A2 and polymorphic CYP2D6 in steady-state concentration of olanzapine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 23(2):119–127

Castle D, Sham P, Murray R (1998) Differences in distribution of ages of onset in males and females with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 33(3):179–183

Castle DJ, McGrath JA, Kulkarni J (2000) Women and schizophrenia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Castle DJ, Sham PC, Wessely S, Murray RM (1994) The subtyping of schizophrenia in men and women: a latent class analysis. Psychol Med 24(1):41–51

Cotton SM, Lambert M, Schimmelmann BG, Foley DL, Morley KI, McGorry PD, Conus P (2009) Gender differences in premorbid, entry, treatment, and outcome characteristics in a treated epidemiological sample of 661 patients with first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 114(1–3):17–24

de Leon J, Diaz FJ, Aguilar MC, Jurado D, Gurpegui M (2006) Does smoking reduce akathisia? Testing a narrow version of the self-medication hypothesis. Schizophr Res 86(1–3):256–268

Dervaux A, Laqueille X (2007) Tobacco and schizophrenia: therapeutic aspects. Encephale 33(4 Pt 1):629–632

Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J (1976) The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 33(6):766–771

First M, Spittzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J (1995) Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders, patient ediction (SCID-P, Version 2). N. Y. S. P. Institute, Biometrics Research, New York

Goldstein JM (1988) Gender differences in the course of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 145(6):684–689

Goldstein JM, Link BG (1988) Gender and the expression of schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res 22(2):141–155

Goldstein JM, Santangelo SL, Simpson JC, Tsuang MT (1990) The role of gender in identifying subtypes of schizophrenia: a latent class analytic approach. Schizophr Bull 16(2):263–275

Gureje O, Bamidele RW (1998) Gender and schizophrenia: association of age at onset with antecedent, clinical and outcome features. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 32(3):415–423

Guy W (1976) Assessment manual for psychopharmacology, Revised edition, ECDEU. US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Rockville

Hafner H (1998) Onset and course of the first schizophrenic episode. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 14(7):413–431

Hafner H (2003) Gender differences in schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 28(Suppl 2):17–54

Hafner H, an der Heiden W, Behrens S, Gattaz WF, Hambrecht M, Loffler W, Maurer K, Munk-Jorgensen P, Nowotny B, Riecher-Rossler A, Stein A (1998) Causes and consequences of the gender difference in age at onset of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 24(1):99–113

Hafner H, Maurer K, Loffler W, Fatkenheuer B, van der Heiden W, Riecher-Rossler A, Behrens S, Gattaz WF (1994) The epidemiology of early schizophrenia. Influence of age and gender on onset and early course. Br J Psychiatry 164(Suppl 23):29–38

Hafner H, Maurer K, Loffler W, Riecher-Rossler A (1993) The influence of age and sex on the onset and early course of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 162:80–86

Hafner H, Riecher-Rossler A, van der Heiden W, Maurer K, Fatkenheuer B, Loffler W (1993) Generating and testing a causal explanation of the gender difference in age at first onset of schizophrenia. Psychol Med 23(4):925–940

Hafner H, Riecher A, Maurer K, Loffler W, Munk-Jorgensen P, Stromgren E (1989) How does gender influence age at first hospitalization for schizophrenia? A transnational case register study. Psychol Med 19(4):903–918

Hales R, Yudoofsky S, Talbot J (1999) The american psychiatric press textbook of psychiatry. American Psychiatric Press, Washington DC

Hamilton M (1967) Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 6(4):278–296

Iacono WG, Beiser M (1992) Where are the women in first-episode studies of schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull 18(3):471–480

Kelly BD, Feeney L, O’Callaghan E, Browne R, Byrne M, Mulryan N, Scully A, Morris M, Kinsella A, Takei N, McNeil T, Walsh D, Larkin C (2004) Obstetric adversity and age at first presentation with schizophrenia: evidence of a dose-response relationship. Am J Psychiatry 161(5):920–922

Kendler KS, Walsh D (1995) Gender and schizophrenia. Results of an epidemiologically-based family study. Br J Psychiatry 167(2):184–192

Kohler S, van der Werf M, Hart B, Morrison G, McCreadie R, Kirkpatrick B, Verkaaik M, Krabbendam L, Verhey F, van Os J, Allardyce J (2009) Evidence that better outcome of psychosis in women is reversed with increasing age of onset: a population-based 5-year follow-up study. Schizophr Res 113:226–232

Koster A, Lajer M, Lindhardt A, Rosenbaum B (2008) Gender differences in first episode psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 43(12):940–946

Kring AM, Moran EK (2008) Emotional response deficits in schizophrenia: insights from affective science. Schizophr Bull 34(5):819–834

Lambert M, Conus P, Lubman DI, Wade D, Yuen H, Moritz S, Naber D, McGorry PD, Schimmelmann BG (2005) The impact of substance use disorders on clinical outcome in 643 patients with first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 112(2):141–148

Larsen TK, Moe LC, Vibe-Hansen L, Johannessen JO (2000) Premorbid functioning versus duration of untreated psychosis in 1 year outcome in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 45(1–2):1–9

Leung A, Chue P (2000) Sex differences in schizophrenia, a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 401:3–38

Lewis SW, Owen MJ, Murray RM (1989) Obstetric complications and schizophrenia: methodology and mechanisms. In: Schulz SC, Tamminga CA (eds) Schizophrenia. A scientific focus. Oxford University Press, New York

Lindstrom E, von Knorring L (1994) Symptoms in schizophrenic syndromes in relation to age, sex, duration of illness and number of previous hospitalizations. Acta Psychiatr Scand 89(4):274–278

Lingjaerde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, Dencker SJ, Elgen K (1987) The UKU side effect rating scale. A new comprehensive rating scale for psychotropic drugs and a cross-sectional study of side effects in neuroleptic-treated patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 334:1–100

Maric N, Krabbendam L, Vollebergh W, de Graaf R, van Os J (2003) Sex differences in symptoms of psychosis in a non-selected, general population sample. Schizophr Res 63(1–2):89–95

Mattsson M, Flyckt L, Edman G, Nyman H, Cullberg J, Forsell Y (2007) Gender differences in the prediction of 5-year outcome in first episode psychosis. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 16(4):208–218

McGlashan TH, Bardenstein KK (1990) Gender differences in affective, schizoaffective, and schizophrenic disorders. Schizophr Bull 16(2):319–329

McGrath JJ (2006) Variations in the incidence of schizophrenia: data versus dogma. Schizophr Bull 32(1):195–197

Moller HJ, Jager M, Riedel M, Obermeier M, Strauss A, Bottlender R (2010) The Munich 15-year follow-up study (MUFUSSAD) on first-hospitalized patients with schizophrenic or affective disorders: comparison of psychopathological and psychosocial course and outcome and prediction of chronicity. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 260(5):367–384

Morgan VA, Castle DJ, Jablensky AV (2008) Do women express and experience psychosis differently from men? Epidemiological evidence from the Australian National Study of Low Prevalence (Psychotic) Disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 42(1):74–82

Murray RM, Lewis SW, Reveley AM (1985) Towards an aetiological classification of schizophrenia. Lancet 1(8436):1023–1026

Nicole L, Shiriqui CH (1995) Gender differences in schizophrenia. In: Shiriqui CH, Nasrallah HA (eds) Contemporary issues in the treatment of schizophrenia. American Psychiatric Press, Washington, pp 225–243

Peralta V, Cuesta M (1994) Validación de la escala de los síndromes positivo y negativo (PANSS) en una muestra de esquizofrénicos españoles. Actas Luso- Esp Neurol Psiquiatr 22(4):171–177

Pinals DA, Malhotra AK, Missar CD, Pickar D, Breier A (1996) Lack of gender differences in neuroleptic response in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 22(3):215–222

Preston NJ, Orr KG, Date R, Nolan L, Castle DJ (2002) Gender differences in premorbid adjustment of patients with first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 55(3):285–290

Scully PJ, Quinn JF, Morgan MG, Kinsella A, O’Callaghan E, Owens JM, Waddington JL (2002) First-episode schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other psychoses in a rural Irish catchment area: incidence and gender in the Cavan-Monaghan study at 5 years. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 43:s3–s9

Seeman MV (2000) Women and schizophrenia. Medscape Womens Health 5(2):2

Seeman MV (2004) Gender differences in the prescribing of antipsychotic drugs. Am J Psychiatry 161(8):1324–1333

Seeman MV, Lang M (1990) The role of estrogens in schizophrenia gender differences. Schizophr Bull 16(2):185–194

Szymanski S, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Mayerhoff D, Loebel A, Geisler S, Chakos M, Koreen A, Jody D, Kane J et al (1995) Gender differences in onset of illness, treatment response, course, and biologic indexes in first-episode schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 152(5):698–703

Thorup A, Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Ohlenschlaeger J, Christensen T, Krarup G, Jorgensen P, Nordentoft M (2007) Gender differences in young adults with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders at baseline in the Danish OPUS study. J Nerv Ment Dis 195(5):396–405

Usall J, Haro JM, Ochoa S, Marquez M, Araya S (2002) Influence of gender on social outcome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 106(5):337–342

Usall J, Ochoa S, Araya S, Gost A, Busquets E (2000) Symptomatology and gender in schizophrenia. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 28(4):219–223

Usall J, Ochoa S, Araya S, Marquez M (2003) Gender differences and outcome in schizophrenia: a 2-year follow-up study in a large community sample. Eur Psychiatry 18(6):282–284

Usall J, Suarez D, Haro JM (2007) Gender differences in response to antipsychotic treatment in outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 153(3):225–231

Verdoux H, Geddes JR, Takei N, Lawrie SM, Bovet P, Eagles JM, Heun R, McCreadie RG, McNeil TF, O’Callaghan E, Stober G, Willinger MU, Wright P, Murray RM (1997) Obstetric complications and age at onset in schizophrenia: an international collaborative meta-analysis of individual patient data. Am J Psychiatry 154(9):1220–1227

Verdoux H, Liraud F, Bergey C, Assens F, Abalan F, van Os J (2001) Is the association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome confounded? A two year follow-up study of first-admitted patients. Schizophr Res 49(3):231–241

Wechsler D (1974) Wechsler intelligence scale for children-revised manual. Psychological Corporation, New York

Willhite RK, Niendam TA, Bearden CE, Zinberg J, O’Brien MP, Cannon TD (2008) Gender differences in symptoms, functioning and social support in patients at ultra-high risk for developing a psychotic disorder. Schizophr Res 104(1–3):237–245

Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA (1978) A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 133:429–435

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Janssen-Cilag. The sponsor played no role in the study design, data collection/analysis/interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The authors had unlimited access to data. Arantzazu Zabala was supported by the University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU GIU 09/37.

Conflict of interest

Dr Gutierrez has acted as consultant, advisor, or speaker for the following companies: Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, and Servier. Dr Eguiluz has acted as consultant, advisor, or speaker for the following companies: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Elli Lilly, and Janssen-Cilag. Dr Segarra has acted as consultant, advisor, or speaker for the following companies: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Elli Lilly, and Janssen-Cilag. The other authors have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Segarra, R., Ojeda, N., Zabala, A. et al. Similarities in early course among men and women with a first episode of schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 262, 95–105 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-011-0218-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-011-0218-2