Abstract

Early-onset bipolar disorder is an impairing condition that is strongly associated with genetic inheritance. Neurocognitive deficits are core traits of this disorder which seem to be present in both young and adult forms. Deficits in verbal memory and attention are persistent within euthymic phases in bipolar adults, adolescents, and children. In younger samples, including type I or II and not otherwise specified patients, executive functions are not widely impaired and the existence of visual-spatial deficits remains unclear. The main aim of this study was to compare the neurocognitive performance in young stabilized type I or II bipolar patients and healthy controls. Fifteen medicated adolescents with bipolar disorder and 15 healthy adolescents, matched in age and gender, were compared on visual-spatial skills (reasoning, memory, visual–motor accuracy) and executive functioning (attention and working memory, set-shifting, inhibition) using t-tests and MANCOVA. Correcting for verbal competence, MANCOVA showed that patients performed significantly worse than controls in letters and numbers sequencing (P = 0.003), copy (P < 0.001) and immediate recall (P = 0.007) of the Rey Complex Figure Test, interference of the Stroop Color-Word Test (P = 0.007) and non-perseverative errors on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (P = 0.038). Impaired cognitive performance was found in young bipolar patients in working memory, visual-motor skills, and inhibitory control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The terms “Early-onset bipolar disorder” (EOBD) and “Pediatric bipolar disorder” (PBD) are used to define cases that begin during childhood and adolescence. The condition affects between 0.6 and 2% of the child and adolescent population and between 2 and 8% in clinical populations [29, 61]. The risk increases to 15% in children and adolescents with a parent with bipolar disorder (BD) [6]. EOBD causes significant impairment, accompanied by elated or irritable mood, rages, rapid cycling, conduct disorders, and substantial psychiatric and psychosocial morbidity [9].

In most cases, the neurocognitive function is clearly affected throughout the patient’s lifetime and, in consequence, neurocognitive deficits are believed to be the important markers of the biologic roots of the disorder [23]. A great deal of research, based mainly on adult onset forms, has tried to isolate the internal cognitive phenotype of BD. Deficits in verbal memory, attention, visual spatial processes, and executive functions have frequently been described within adults suffering from BD [34, 45, 50, 55]. Some of these neuropsychological deficits, such as verbal learning, verbal memory, or cognitive set-shifting, appear to be related to the presence of mild symptoms of the affective disorder [47]. Similarly, other studies have found that the deficits in declarative memory, verbal fluency, or psychomotor speed are related to the negative influence of recurrent manic episodes, the number of hospitalizations, the presence of psychotic symptoms or the duration, and doses of the pharmacological treatment [22, 30, 32, 33, 63].

However, the persistence of poor performance on these tasks in euthymic adult patients and in their unaffected relatives suggests that these specific deficits may be putative endophenotypes [7, 11, 23, 27, 48]. Moreover, a growing if not entirely consistent body of literature also defines executive dysfunctions [4, 8, 17] and deficits in visual-spatial skills as endophenotypic traits of bipolar disorder [20, 44].

The greater clinical severity of EOBD compared with adult bipolar disorder forms, and the possibility that this difference may have a biologic etiology, have stimulated the search for cognitive deficits [18, 42]. Efforts to determine, and limit, the effects of possible deficits at early ages should be a major focus of assessment and treatment planning.

To our knowledge, neurocognitive functioning in young bipolar patients has not been analyzed in depth. The works that have been published report a non-unitary variety of neurocognitive deficits [14, 36, 38]. The specificity of the attention deficits has been questioned: some studies have described similarities in performance on sustained attention tests in stabilized young bipolar patients, unipolar patients, and healthy controls or between controls, unaffected and affected remitted high-risk offspring of BD parents [16, 46], while others have shown that this neurocognitive deficits appear in BD in cases of co-morbidity with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [49]. However, as in adults, the majority of studies have reported major impairment in verbal fluency, verbal memory, and attention tasks in both manic and euthymic pediatric patients compared to controls [15, 21, 43]. These results point consistently toward a common deficit among adults, children, and adolescents.

Although a recent meta-analysis of EOBD/PBD confirmed this verbal memory impairment as the more robust deficit [26], the findings for executive functions are still inconclusive. Inhibition and working memory dysfunctions have not been consistently found to be low in young BD patients in most studies [13–15, 46], while difficulties in set-shifting or problem solving were detected in only a few of them [38, 43].

Another point of interest is visual-spatial ability in younger patients. Although some studies detected and analyzed visual-spatial memory deficits in bipolar adolescents [13, 37], others failed to find differences with regard to healthy subjects [14, 25, 43]. Despite these inconsistent initial findings, moderate effect sizes were associated with specific deficits in visual-spatial perception, visual memory, and motor skills in the meta-analysis conducted by Joseph et al. [26]. Nevertheless, only five of the included studies considered the measures of visual-motor skills, in spite of the fact that they appear to be an innovative area of study in other child and adolescent pathologies, like ADHD, obsessive compulsive disorder, or autism spectrum disorders [1, 10, 58]. Further research in this area should be conducted in patients with EOBD/PBD.

Also controversial are the characteristics of the studied samples classified in the categories of EOBD or PBD. Some of these samples, in principal those referred as PBD, included cases ranging from prepubertal onset to adolescent and included several subtypes, as type I or type II, or not otherwise specified form (NOS-BD). However, the clinical manifestation of BD is different from a child to an adult, and consensus has not been still achieved about their diagnostic criteria [5, 9, 31]. Because of the lack of conclusive scientific agreement, it is conceivable that the samples were heterogeneous and the etiopathogenesis of these cases may be different [29, 42]. In consequence, it would result difficult to find consistency within neurocognitive profiles across the samples of different studies in relation to executive functioning and visual-spatial performance. Recently, a committee of experts on child and adolescence bipolar disorder—supported by the American Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry—stated the term “Early-onset bipolar disorder (EOBD)” for patients younger than 18 years and the term “Very early-onset bipolar disorder (VEOBD)” for patients younger than 12 and proposed a corpus of unified criteria for their diagnostics [9].

As deficits on verbal memory and sustained attention have been clearly demonstrated in children and adolescent bipolar patients as well as in adults, the main aim of this study was to compare neurocognitive performance in a group of adolescents with EOBD and a group of healthy age- and gender-matched controls in the most controversial domains, such as working memory, visual–spatial–motor skills and executive functions of inhibition, and set-shifting. We hypothesized that EOBD patients would perform worse than matched controls on all these tasks, except in set-shifting.

We focused on the functioning of patients with an adolescent onset of type I or II BD, forms of the disorder that are quite similar to the adult manifestation of these subtypes. As a result, we refer to our case sample as “Early-onset bipolar disorder (EOBD)” and not as pediatric bipolar disorder (PBD).

Patients and methods

Design

This is a cross-sectional controlled study, with two matched samples.

Sample

Thirty subjects, from 15 to 17 years, were assessed during 2007 and 2008. Fifteen presented EOBD (12 of type I and 3 of type II), and 15 were healthy matched controls. In each subgroup, 53% were female and 47% were male. Patients were recruited from the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology of Hospital Clínic, in Barcelona, where they had been diagnosed and were receiving treatment. Controls were from the same city district; they were recruited as volunteers through public advertisements and received financial compensation. The semi-structured interview Kiddie-SADS-PL was administered to confirm the diagnosis of BD in cases, according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria, and to exclude psychopathology in controls. Patients were euthymic and had not had psychotic symptoms for at least 3 months before the neuropsychological evaluation. At the time of inclusion, all patients fulfilled the following criteria: (a) diagnosis of type I or II BD; (b) scores <20 on the Brief Psychosis Rating Scale (BPRS), <18 in the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and <14 in the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS). The exclusion criteria were the following: (a) acute symptomatology, (b) not otherwise specified-BD, and (c) neurological disease or mental retardation (Intellectual Quotient Full Scale < 70, weighted from the Vocabulary and Block Design of Wechsler scales of intelligence). All EOBD patients were receiving mood-stabilizing medication (11 lithium 800–1,200 mg, 3 valproate 400–1,000 mg, 1 oxcarbamacepine 1,200 mg), 11 of them a co-adjuvant antipsychotic (4 risperidone 2–8 mg, 4 olanzapine 5–20 mg, 3 quetiapine 100–800 mg), and three cases were receiving antidepressants (2 sertraline 50–100 mg, 1 fluvoxamine 150 mg). Sociodemographic and clinical data are shown in Table 1. The study was described to all participants and families, and written informed consent was obtained. These study procedures were approved by the local ethical committees.

Measures

All subjects’ cognitive performance was assessed with the same battery of neuropsychological tests, detailed in Table 2. Scores were recorded in accordance with Spanish normative data, with mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10.

Statistical analysis

Despite the small sample size, almost all measures were distributed normally according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (P values ranged from 0.13 to 0.20), except for RCFT copy and Immediate recall (P = 0.026 and 0.03). Taking these results into account, nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-tests for RCFT measures and parametric t-tests for the rest of measures were carried out initially to compare patient and control groups. When nonparametric tests showed statistically significant differences, parametric tests were calculated in order to simplify data. In the second stage, the scores of both groups were compared using MANCOVA test (adjusted for the vocabulary test score). The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

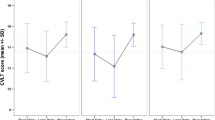

Samples were similar in age and gender, as expected from the matching procedure. EOBD patients scored lower than healthy controls on all measures (Table 3; Fig. 1). T-tests showed significant differences in vocabulary, digit span, letters and numbers sequencing, immediate recall of WMS-III visual memory, and the non-perseverative errors index of WCST. Nonparametric tests showed significant differences in RCFT variables between groups (Mann–Whitney U-test; RCFT copy: z = −3.49, P < 0.001; RCFT immediate recall: z = −2.38, P = 0.016) (in Table 3, t-test values are also described for these variables). The contrast in Block Design and Interference Index of the Stroop Test came close to statistical difference. No significant differences were found on Delayed recall of WMS-III Visual memory and perseverative errors of the WCST. In summary, EOBD subjects performed around one standard deviation worse than healthy controls on tasks of attention, working memory, visual-spatial immediate memory, visual-motor accuracy, and inhibitory control.

However, as differences on vocabulary test mean scores were observed between groups, a MANCOVA was conducted in order to retest the differences between cases and controls, controlling for their verbal competence. Therefore, the model reflected significant global differences (F = 4.24, P = 0.007) and test-specific differences between groups in letters and numbers, Stroop interference index, copy and immediate recall of RCFT, and non-perseverative errors of WCST (Table 3). The differences on digit span and Immediate recall of WMS-III Visual memory found previously disappeared when adjusted for verbal competence.

Discussion

Bipolar adolescents performed worse than healthy adolescents in all measures, with significant differences in various tasks of executive functions and visual-spatial skills, differences that raised and exceeded one standard deviation from unaffected controls (Fig. 1). Controlling for verbal IQ, the statistical differences between EOBD and healthy adolescents remained on attention, working memory, visual-motor accuracy, and inhibitory control. In accordance with our hypothesis, deficits in almost all the executive functions were observed, except for set-shifting tasks. However, we did not detect deficits in visual memory or visual-spatial reasoning, as expected.

Previous literature reports have described similar dysfunctions in similar degree. First, the impairment of attention and working memory has been observed in several studies, in both adults and adolescents [7, 11, 26, 34]. Our data suggest that the higher the demand on working memory (letter and number in front of digit span), the greater the difference in performance between patients and controls. Other studies with different procedures, such as CPT-Identical Pairs, found poorer performance with increased working memory in young bipolar patients [12]. However, Joseph et al. [26] reported that the attention deficit in pediatric bipolar patients did not differ from that observed in other psychiatric disorders and therefore suggested that it was an unspecified impairment. In our study, the difference in selective attention (digit span) disappeared when verbal competence was controlled.

Secondly, a principal deficit in general executive function was observed in our sample. Significant worse scores were recorded in bipolar patients on inhibitory control (Stroop interference index, non-perseverative errors WCST) than in healthy subjects. As reported in adult studies [39, 59], patients had a stronger tendency to miss the predominant criteria that guide toward the right answer, reflecting deficits in the inhibition of distracters and in the maintenance of the target response. These deficits have been attributed to dysfunctions in the ventral prefrontal cortex [7, 19, 23, 24] and have been suggested to be a core cognitive trait in BD, probably linked to the etiological pathway of the disorder. Nevertheless, we did not detect decreased performance in our sample on the set-shifting executive task (perseverative errors of WCST). By contrast, some studies with pediatric and adult samples have found moderate effect sizes related to a worse performance on overall WCST and Trail Making Test (TMT) measures [43, 59], which suggested deficit in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex functioning.

Third, Frantom et al. [20] observed that deficits in visual-spatial-constructional abilities, executive functions, visual learning, visual memory, and motor speed were present in type I adult bipolar patients as well as in their unaffected relatives. As a result, they proposed visual-motor deficits as a candidate endophenotype. We observed deficits in visual-motor skills within bipolar patients, based on significant differences on copy accuracy and immediate recall accuracy of RCFT, but not in other tasks such as visual-spatial reasoning or visual memory, as Torres et al. [56] observed in bipolar young adults. Probably, the accuracy on immediate recall of RCFT was lower because of the difficulties in the process of copy encoding and visual learning, processes that are considered as impaired by the International Society for Bipolar Disorders- Battery for Assessment of Neurocognition (ISBD-BANC) Committee [59]. Studies with MRI have related the gray matter thinning of the frontal lobe or the decrease in its volume with performance on the RCFT, both in healthy children and adolescents and in children with organic pathologies, suggesting that differences in this task performance could be due to the level of maturation of these cortical areas [2, 52]. Other functional neuroimaging studies have reported relations between arousal and visual-spatial attention in healthy adults, suggesting that there may be overlapping neuronal anatomical networks in the right hemisphere and that functional deficits in attention and visual skills may also be related [24, 38].

Lastly, and unexpectedly, we found verbal competence deficiencies in our sample of bipolar adolescents. To our knowledge, these differences have been reported only by two previous studies in young bipolar patients [14, 41]. Some studies of affected children and adolescents did not consider this measure of verbal ability, while others matched their samples according to IQ. We estimated verbal competence from the Wechsler Vocabulary scale, separated from the performance intellectual functioning (Block Design) and from the Full Score IQ (FSIQ). Although the lower Vocabulary score could be seen as a reflection of a lower intellectual quotient among our bipolar adolescents than in healthy controls, evidence from adult bipolar patients suggests that this consideration is not valid when symptoms are stabilized [8]. Interestingly, our case and control groups did not differ on estimated performance-IQ. This lower verbal competence identified by some reports points to the differences in the ability of cases and healthy subjects to process and react to life events. Furthermore, these verbal deficits may underlie the verbal memory and verbal fluency deficits observed in all BD patients, regardless of their age at onset [21, 28, 43, 54]. In fact, the high correlations between the Auditory Memory Indexes of WMS-III with the Verbal Comprehension Index of WAIS-III (r = 0.54–0.57) reflect this relation between verbal IQ and verbal memory [57].

Our intention in this work was to study a sample of adolescent BD as homogeneous as possible, which comprised only types I and II and excluded NOS forms. Adolescent forms of types I and II BD are similar to the same adult subtypes and neuropsychological profiles between them are quite similar. Only the degree of impairment has been found higher in type I in relation to II in adult BD on some tasks, as inhibitory control and verbal memory, but not in other [55]. However, the category “Pediatric bipolar disorder” is still not considered as a validated and approved by consensus diagnostic category and there are not equivalent diagnostic criteria from one research to another, mainly for NOS type. This lack of consensus probably has influenced the characteristics of the case samples in different studies [5, 9, 31, 60].

The International Society for Bipolar Disorders has recently recommended a neuropsychological battery to use in bipolar disorders according to the deficits found by previous research, the Battery for Assessment of Neurocognition (ISBD-BANC) [59]. Three of the tests used in our study are included in the ISBD-BANC, and other instruments are measures of similar domains recommended. We join to this proposition of battery for future studies.

The preliminary sample size has to be mentioned as a limitation of the present study, which conditioned the ability to analyze differences between subgroups of EOBD. Comparisons between our small subgroups would be invalid. Due to previous discrepant findings, the comparison between EOBD with or without an associated ADHD is of high interest. Whereas some studies found that adolescents with both disorders showed higher deficits on attention, working memory, and executive functions in front of BD alone, others failed in finding differences [13, 25, 43, 46, 49]. Nevertheless, the study of comorbidity with ADHD needs to consider the clinical characteristics of PBD from one study to another, due to the different ratios reported among both diagnostics, ranging from 21 to 60% [3, 35, 51]. In our sample, four of the fifteen bipolar patients had co-morbid ADHD (27%), coincident with the ratios of adult bipolar patients that have presented associated ADHD in lifetime [40, 53].

Other recent studies have put their interest in the degree of neurocognitive impairment depending on the presence of psychotic symptoms or not. In adults, Martínez-Aran et al. [33] found that BD adults with history of psychotic symptoms show slightly more impairment in some executive functions than patients without these symptoms, and worse clinical outcome and significant poorer performance in overall executive functions and working memory tasks than healthy controls. To our knowledge, scientific production about the influence of psychotic symptoms on neurocognitive performance of child and adolescent population is limited. In that sense, Zabala et al. [62] observed that children and adolescents with a first psychotic episode showed worse performance than healthy controls in all neuropsychological domains, but differences were not found between diagnostic groups (schizophrenia, BD, and other psychoses). Therefore, further research is necessary to study the effect of psychosis over the clinical outcome and the cognitive impairment of EOBD.

On the other hand, it has also been investigated the nature of mood episodes over the cognitive functioning. Torres et al. [56] found significant lower scores on both visual-spatial reasoning and set-shifting executive functions in young BD adults recovered from their first manic episode than in unaffected controls; verbal IQ and inhibitory control executive task were similar. These results are completely opposite to ours; in consequence, more research should to be conducted differentiating cognitive impact according to the nature of episodes.

Clinical implications

These findings contribute to the knowledge of EOBD, in order to identify its specific deficits and help to design longitudinal studies that isolate the impairment due to the symptoms emergence from that due to the course of the disorder or the use of treatments. Moreover, this growing corpus of data allows developing programs of neurocognitive training with the aim to reduce the negative impact of the illness over functioning.

Conclusions

Deficits in a wide range of neurocognitive functions were found in relation to euthymic Early-onset bipolar disorder, affecting working memory, visual-motor accuracy, and executive functions of inhibitory control. Further research should be conducted to replicate the presence of these deficits in larger samples of adolescents with BD. It would be interesting to differentiate subgroups according to the type of BD, nature of first mood episode, presence of psychotic symptoms, comorbidity with ADHD, and drug therapies used.

References

Andres S, Boget T, Lazaro L, Penades R, Morer A, Salamero M, Castro-Fornieles J (2007) Neuropsychological performance in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder and influence of clinical variables. Biol Psychiatry 61:946–951

Antshel KM, Peebles J, AbdulSabur N, Higgins AM, Roizen N, Shprintzen R, Fremont WP, Nastasi R, Kates WR (2008) Associations between performance on the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure and regional brain volumes in children with and without velocardiofacial syndrome. Dev Neuropsychol 33:601–622

Axelson D, Birmaher B, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Bridge J, Keller M (2006) Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63:1139–1148

Bearden CE, Freimer NB (2006) Endophenotypes for psychiatric disorders: ready for primetime? Trends Genet 22:306–313

Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV, Spencer T, Wilens TE, Wozniak J (2000) Pediatric mania: a developmental subtype of bipolar disorder? Biol Psychiatry 48:458–466

Birmaher B, Axelson D, Monk K, Kalas C, Goldstein B, Hickey MB, Obreja M, Ehmann M, Iyengar S, Shamseddeen W, Kupfer D, Brent D (2009) Lifetime psychiatric disorders in school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66:287–296

Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C (2009) Cognitive endophenotypes of bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of neuropsychological deficits in euthymic patients and their first-degree relatives. J Affect Disord 113:1–20

Cahill CM, Green MJ, Jairam R, Malhi GS (2007) Do cognitive deficits in juvenile bipolar disorder persist into adulthood? J Nerv Ment Dis 195:891–896

Carlson GA, Findling RL, Post RM, Birmaher B, Blumberg HP, Correll C, DelBello MP, Fristad M, Frazier J, Hammen C, Hinshaw SP, Kowatch R, Leibenluft E, Meyer SE, Pavuluri MN, Wagner KD, Tohen M (2009) AACAP 2006 research forum–advancing research in early-onset bipolar disorder: barriers and suggestions. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 19:3–12

Caron MJ, Mottron L, Berthiaume C, Dawson M (2006) Cognitive mechanisms, specificity and neural underpinnings of visuospatial peaks in autism. Brain 129:1789–1802

Clark L, Goodwin GM (2004) State- and trait-related deficits in sustained attention in bipolar disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 254:61–68

DelBello MP, Adler CM, Amicone J, Mills NP, Shear PK, Warner J, Strakowski SM (2004) Parametric neurocognitive task design: a pilot study of sustained attention in adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 82(Suppl 1):S79–S88

Dickstein DP, Treland JE, Snow J, McClure EB, Mehta MS, Towbin KE, Pine DS, Leibenluft E (2004) Neuropsychological performance in pediatric bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 55:32–39

Doyle AE, Wilens TE, Kwon A, Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Fried R, Swezey A, Snyder L, Biederman J (2005) Neuropsychological functioning in youth with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 58:540–548

Doyle AE, Wozniak J, Wilens TE, Henin A, Seidman LJ, Petty C, Fried R, Gross LM, Faraone SV, Biederman J (2009) Neurocognitive impairment in unaffected siblings of youth with bipolar disorder. Psychol Med 39:1253–1263

Duffy A, Hajek T, Alda M, Grof P, Milin R, MacQueen G (2009) Neurocognitive functioning in the early stages of bipolar disorder: visual backward masking performance in high risk subjects. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 259:263–269

Ferrier IN, Chowdhury R, Thompson JM, Watson S, Young AH (2004) Neurocognitive function in unaffected first-degree relatives of patients with bipolar disorder: a preliminary report. Bipolar Disord 6:319–322

Findling RL, Gracious BL, McNamara NK, Youngstrom EA, Demeter CA, Branicky LA, Calabrese JR (2001) Rapid, continuous cycling and psychiatric co-morbidity in pediatric bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord 3:202–210

Frangou S, Haldane M, Roddy D, Kumari V (2005) Evidence for deficit in tasks of ventral, but not dorsal, prefrontal executive function as an endophenotypic marker for bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 58:838–839

Frantom LV, Allen DN, Cross CL (2008) Neurocognitive endophenotypes for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 10:387–399

Glahn DC, Bearden CE, Caetano S, Fonseca M, Najt P, Hunter K, Pliszka SR, Olvera RL, Soares JC (2005) Declarative memory impairment in pediatric bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 7:546–554

Gruber SA, Rosso IM, Yurgelun-Todd D (2008) Neuropsychological performance predicts clinical recovery in bipolar patients. J Affect Disord 105:253–260

Hasler G, Drevets WC, Gould TD, Gottesman II, Manji HK (2006) Toward constructing an endophenotype strategy for bipolar disorders. Biol Psychiatry 60:93–105

Heber IA, Valvoda JT, Kuhlen T, Fimm B (2008) Low arousal modulates visuospatial attention in three-dimensional virtual space. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 14:309–317

Henin A, Mick E, Biederman J, Fried R, Wozniak J, Faraone SV, Harrington K, Davis S, Doyle AE (2007) Can bipolar disorder-specific neuropsychological impairments in children be identified? J Consult Clin Psychol 75:210–220

Joseph MF, Frazier TW, Youngstrom EA, Soares JC (2008) A quantitative and qualitative review of neurocognitive performance in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 18:595–605

Keri S, Kelemen O, Benedek G, Janka Z (2001) Different trait markers for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a neurocognitive approach. Psychol Med 31:915–922

Kravariti E, Reichenberg A, Morgan K, Dazzan P, Morgan C, Zanelli JW, Lappin JM, Doody GA, Harrison G, Jones PB, Murray RM, Fearon P (2009) Selective deficits in semantic verbal fluency in patients with a first affective episode with psychotic symptoms and a positive history of mania. Bipolar Disord 11:323–329

Lazaro L, Castro-Fornieles J, de la Fuente JE, Baeza I, Morer A, Pamias M (2007) Differences between prepubertal- versus adolescent- onset bipolar disorder in a Spanish clinical sample. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 16:510–516

Lebowitz BK, Shear PK, Steed MA, Strakowski SM (2001) Verbal fluency in mania: relationship to number of manic episodes. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 14:177–182

Leibenluft E, Cohen P, Gorrindo T, Brook JS, Pine DS (2006) Chronic versus episodic irritability in youth: a community-based, longitudinal study of clinical and diagnostic associations. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 16:456–466

Marneros A, Rottig S, Rottig D, Tscharntke A, Brieger P (2009) Bipolar I disorder with mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms: a comparative longitudinal study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 259:131–136

Martinez-Aran A, Torrent C, Tabares-Seisdedos R, Salamero M, Daban C, Balanza-Martinez V, Sanchez-Moreno J, Manuel GJ, Benabarre A, Colom F, Vieta E (2008) Neurocognitive impairment in bipolar patients with and without history of psychosis. J Clin Psychiatry 69:233–239

Martinez-Aran A, Vieta E, Reinares M, Colom F, Torrent C, Sanchez-Moreno J, Benabarre A, Goikolea JM, Comes M, Salamero M (2004) Cognitive function across manic or hypomanic, depressed, and euthymic states in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 161:262–270

Masi G, Perugi G, Toni C, Millepiedi S, Mucci M, Bertini N, Pfanner C (2006) Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder–bipolar comorbidity in children and adolescents. Bipolar Disord 8:373–381

McCarthy J, Arrese D, McGlashan A, Rappaport B, Kraseski K, Conway F, Mule C, Tucker J (2004) Sustained attention and visual processing speed in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder and other psychiatric disorders. Psychol Rep 95:39–47

McClure EB, Treland JE, Snow J, Dickstein DP, Towbin KE, Charney DS, Pine DS, Leibenluft E (2005) Memory and learning in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44:461–469

McClure EB, Treland JE, Snow J, Schmajuk M, Dickstein DP, Towbin KE, Charney DS, Pine DS, Leibenluft E (2005) Deficits in social cognition and response flexibility in pediatric bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 162:1644–1651

Mur M, Portella MJ, Martinez-Aran A, Pifarre J, Vieta E (2008) Neuropsychological profile in bipolar disorder: a preliminary study of monotherapy lithium-treated euthymic bipolar patients evaluated at a 2-year interval. Acta Psychiatr Scand 118:373–381

Nierenberg AA, Miyahara S, Spencer T, Wisniewski SR, Otto MW, Simon N, Pollack MH, Ostacher MJ, Yan L, Siegel R, Sachs GS (2005) Clinical and diagnostic implications of lifetime attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder comorbidity in adults with bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 STEP-BD participants. Biol Psychiatry 57:1467–1473

Olvera RL, Semrud-Clikeman M, Pliszka SR, O’Donnell L (2005) Neuropsychological deficits in adolescents with conduct disorder and comorbid bipolar disorder: a pilot study. Bipolar Disord 7:57–67

Pavuluri MN, Birmaher B, Naylor MW (2005) Pediatric bipolar disorder: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44:846–871

Pavuluri MN, Schenkel LS, Aryal S, Harral EM, Hill SK, Herbener ES, Sweeney JA (2006) Neurocognitive function in unmedicated manic and medicated euthymic pediatric bipolar patients. Am J Psychiatry 163:286–293

Pirkola T, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Glahn D, Kieseppa T, Haukka J, Kaprio J, Lonnqvist J, Cannon TD (2005) Spatial working memory function in twins with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 58:930–936

Quraishi S, Frangou S (2002) Neuropsychology of bipolar disorder: a review. J Affect Disord 72:209–226

Robertson HA, Kutcher SP, Lagace DC (2003) No evidence of attentional deficits in stabilized bipolar youth relative to unipolar and control comparators. Bipolar Disord 5:330–339

Robinson LJ, Ferrier IN (2006) Evolution of cognitive impairment in bipolar disorder: a systematic review of cross-sectional evidence. Bipolar Disord 8:103–116

Robinson LJ, Thompson JM, Gallagher P, Goswami U, Young AH, Ferrier IN, Moore PB (2006) A meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 93:105–115

Rucklidge JJ (2006) Impact of ADHD on the neurocognitive functioning of adolescents with bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 60:921–928

Seidman LJ, Kremen WS, Koren D, Faraone SV, Goldstein JM, Tsuang MT (2002) A comparative profile analysis of neuropsychological functioning in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar psychoses. Schizophr Res 53:31–44

Soutullo CA, Escamilla-Canales I, Wozniak J, Gamazo-Garran P, Figueroa-Quintana A, Biederman J (2009) Pediatric bipolar disorder in a Spanish sample: features before and at the time of diagnosis. J Affect Disord 118:39–47

Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Tessner KD, Toga AW (2001) Mapping continued brain growth and gray matter density reduction in dorsal frontal cortex: Inverse relationships during postadolescent brain maturation. J Neurosci 21:8819–8829

Tamam L, Karakus G, Ozpoyraz N (2008) Comorbidity of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder: prevalence and clinical correlates. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 258:385–393

Thompson JM, Gray JM, Crawford JR, Hughes JH, Young AH, Ferrier IN (2009) Differential deficit in executive control in euthymic bipolar disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 118:146–160

Torrent C, Martinez-Aran A, Daban C, Sanchez-Moreno J, Comes M, Goikolea JM, Salamero M, Vieta E (2006) Cognitive impairment in bipolar II disorder. Br J Psychiatry 189:254–259

Torres IJ, Defreitas VG, Defreitas CM, Kauer-Sant’anna M, Bond DJ, Honer WG, Lam RW, Yatham LN (2010) Neurocognitive functioning in patients with bipolar I disorder recently recovered from a first manic episode. J Clin Psychiatry

Wechsler D (2004) Escala de Memoria de Wechsler-III. Madrid, TEA Ediciones

Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Nigg JT, Faraone SV, Pennington BF (2005) Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Biol Psychiatry 57:1336–1346

Yatham LN, Torres IJ, Malhi GS, Frangou S, Glahn DC, Bearden CE, Burdick KE, Martinez-Aran A, Dittmann S, Goldberg JF, Ozerdem A, Aydemir O, Chengappa KN (2010) The International Society for Bipolar Disorders-Battery for Assessment of Neurocognition (ISBD-BANC). Bipolar Disord 12:351–363

Youngstrom EA, Birmaher B, Findling RL (2008) Pediatric bipolar disorder: validity, phenomenology, and recommendations for diagnosis. Bipolar Disord 10:194–214

Youngstrom EA, Findling RL, Youngstrom JK, Calabrese JR (2005) Toward an evidence-based assessment of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 34:433–448

Zabala A, Rapado M, Arango C, Robles O, de la SE, Gonzalez C, Rodriguez-Sanchez JM, Andres P, Mayoral M, Bombin I (2010) Neuropsychological functioning in early-onset first-episode psychosis: comparison of diagnostic subgroups. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 260:225–233

Zubieta JK, Huguelet P, O’Neil RL, Giordani BJ (2001) Cognitive function in euthymic bipolar I disorder. Psychiatry Res 102:9–20

Acknowledgments

We thank ‘Fundación Alicia Koplowitz’ (2006-2008) and ‘Grup de Recerca Consolidat de l’Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR) de la Generalitat’ (2009 SGR1119) for the financial funding for this work. We thank Montse Pàmias Massana and Samuel López Alcalde their help in the implementation of this project and Olga Puig their contribution with the recruitment of the control sample.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00406-010-0180-4

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lera-Miguel, S., Andrés-Perpiñá, S., Calvo, R. et al. Early-onset bipolar disorder: how about visual-spatial skills and executive functions?. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 261, 195–203 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-010-0169-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-010-0169-z