Abstract

This review presents a comprehensive and updated overview of bigerminal choristomas (hairy polyps) of naso-oropharynx/oral cavity, and discusses the controversies related to nosology and origin from a clinico-embryologic perspective. English-language texts of the last 25 years (January 1989–January 2014) were collected from the PubMed/MEDLINE database using the given keywords. Of the 330 records, 64 full-text articles (mostly case reports/series) were selected, incorporating clinical data from 78 patients, after screening through duplicates and the given exclusion criteria. With the available evidence, hairy polyps appear more common than generally believed, and are increasingly being recognized as an important, often-missed cause of respiratory distress and feeding difficulty in neonates and infants. Such a child without any apparent cause should be examined with flexible nasopharyngoscope to specifically look for hairy polyps which might be life-threatening, especially when small. The female preponderance as believed today has been found to be an overestimation in this review. These lesions are characteristically composed of mature ectodermal and mesodermal tissue derivatives presenting as heterotopic masses, hence termed choristoma. However, little is known about their origin, and whether they are developmental malformations or primitive teratomas is debatable. Involvement of Eustachian tube and tonsils as predominant subsites and the speculated molecular embryogenesis link hairy polyps to the development of the first and second pharyngeal arches. They are exceptionally rare in adults, but form a distinct entity in this age-group and could be explained as delayed pluripotent cell morphogenesis or focal neoplastic malformations, keeping with the present-day understandings of the expanded “teratoma family”.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mature bigerminal lesions, the so-called hairy polyps, have continued to generate interest as well as controversy among the clinicians and developmental biologists till date. Such lesions, a choristoma according to one school of authors, have been most commonly reported in the naso-oropharynx within the head-neck region. “Choristoma” by definition is the aggregation of mature polygerminal tissue at anatomic areas where they are not destined to be. The term is often discussed in conjunction with “hamartoma” where such tissue is present in its mother organ system. Choristomas are ubiquitous in the body, yet are poorly understood and seldom explored. A classic example in the otolaryngologic purview is the hairy polyp which presents at birth or early infancy as pedunculated polypoid mass mostly from the naso-oropharynx (Fig. 1), and histologically composed of derivatives of ectoderm (epithelium, hair follicles, sebaceous and sweat glands) and mesoderm (fibro-adipose tissue, cartilage and muscle fibers) (Fig. 2). However, current literature is not unanimous on the question whether they in essence are part of the spectrum of well-described congenital defects like developmental aberrations or teratomas, or belong to the family of neoplastic disorders. Their occurrence in adults, though extremely rare, has further complicated the issue. Clinically, they present with obstructive features owing to mass effect, but may remain hidden or undiagnosed resulting in more sinister consequences that warrant a high index of suspicion from the attending clinicians. Through this review of bigerminal choristomatous lesions in the naso-oropharynx, we have attempted to present a comprehensive clinical overview and also dealt with the controversies in nosology with discussions on the plausible theories of origin from a clinico-embryologic perspective.

A classic example of histopathology of a hairy polyp showing mature tissue elements of both ectodermal and mesodermal origin, including stratified squamous epithelium, skin adnexa (hair follicle, sebaceous glands), fibro-adipose tissue and muscle fibers [hematoxylin and eosin, ×100] (reproduced from reference 59; Hindawi Publishing Corporation; Open access)

Methodology

Data from English-language texts (including “online first”/ahead of print) of the last 25 years (January 1989–January 2014) were collected from the PubMed/MEDLINE database using the given keywords. Only the cases of bigerminal (ectodermal and mesodermal) choristomas resembling the classic description of “hairy polyp/dermoid” [Arnold’s classification [1] (Table 1)] were considered. Figure 3 provides a detailed overview on how the selection and screening were done. The keywords “hairy polyp”, “dermoid” and “choristoma” were paired up with the rest, and the results recorded in each case forming a collective list. Initial search revealed 307 records which were reviewed independently by two authors. During the process, it was noticed that the Eustachian tube formed a predominant area of involvement in the nasopharynx. As the nasopharynx is anatomically and embryologically linked with the Eustachian tube and middle ear system, cases where such lesions originated within the Eustachian tube with variable extensions were also included. The search was therefore refined using “Eustachian tube” as another keyword, and 23 more citations were retrieved. Of these 330 records, 168 were selected when the duplicates from the collective list were removed. Applying the exclusion criteria (Fig. 3), 65 articles were considered for evaluation of the full text, of which one was later excluded. Bibliography of the articles reviewed was further cross-checked so that no subject was missed within the time-period under consideration. Almost all articles were case reports/series; the 4 reviews obtained were designed primarily as extensive literature search, but no well-structured systematic reviews or meta-analyses were found. Overall, 60 case reports/series and 4 review articles, with a total of 78 patients, were considered for inclusion in the present analysis (Table 2). Information from the systematic review by Muzzi et al. [2] dealing with the nosology of “tumor and tumor-like” lesions of the Eustachian tube was used in “Discussion” section of the present review, but there was no scope of its inclusion in the clinical analysis. The results were tabulated and analyzed for distribution among age-groups, sex, anatomic subsites involved, laterality and symptoms, aiming to establish a comprehensive clinical overview. Recent trends in management were also noted. Clinically relevant theoretical and molecular embryology deducible from the outcomes of the present clinical analysis along with the classification system have been discussed at appropriate places with special emphasis on adults, obtaining information from the articles reviewed, and also from related textbooks chapters on embryology and other recent journal citations.

Discussion

The Arnold’s classification and choristoma

The complex germ-layer lesions of the naso-oropharynx—the so-called “dysontogenetic nasopharyngeal tumors”—have been traditionally classified by Arnold in 1870 into dermoid, teratoid, teratoma and epignathi [1] (Table 1). The concept is still in vogue; however, their categorical distinction by histogenesis, tissue composition and order of cellular maturity remains controversial. The primitive pharyngeal gut develops primarily from pharyngeal arches with orderly incorporation of migrating neural crest cells from rhombomeres in the hindbrain to the intrinsic arch mesenchyme [3]. In utero alterations in the process occasionally result in persistence of histologically normal heterotopic cell-rests of one or more germ-line lineage as raised non-neoplastic masses. These lesions, erroneously separated from the mother/target tissue, have led researchers refer them as choristoma (choristo = separated). Arnold’s classification was based on germ-layer composition and their maturity; these lesions when encountered in aberrant anatomic sites have often been addressed as choristoma as an alternative.

Hairy polyp as choristoma—incidence and origin in children and adults

Hairy polyps, the commonest congenital tumor of the naso-oropharynx [4, 5], was first reported in 1784 [6] and described by Brown-Kelly in 1918 [7]. With an incidence of 1 in 40,000 live births [8, 9], they mostly affect female neonates. Their occurrence beyond age 20 years is considered exceptional [10]; there have been only 5 reports in adults in the last 25 years [10–13], with 2 reports in 2013 itself (Table 2, Fig. 4). Neonates constitute almost 37 % of the cases, more than half presenting at birth or within day one (Table 3). Kelly et al. [4] in the pre-PubMed era stated that more than 50 % of such lesions presented in infancy, however, we found this to be about 36 %; with the neonates included, the figure stands at about 73 % (Table 3). This along with the fact that a fetus was once reported to harbor a hairy polyp necessitating termination of pregnancy [14] strongly suggests that they are primarily developmental aberrations. However, this does not satisfactorily explain their occurrence in adults. Though the origin of bigerminal choristomas in the naso-oropharynx is not known, theories have been put forward (Table 4). Central to the understanding is the concept that owing to an inciting factor (trauma, etc.), pluripotent cells during development get released from local governing influences that would have otherwise led them to the pre-destined tissue morphogenesis [9, 15, 16], or gets misdirected or trapped during migration so that they cannot reach the targeted organ (the “missed target hypothesis”) [9, 17, 18], forming heterotopic tissues. As choristomas are ubiquitous in the body, this would explain their occurrence both at the embryonal fusion points and also at sites with no plausible embryologic connection. Therefore, their occurrence in adults—Resta et al. reporting a hairy polyp in a 71-year-old man [19]—could be a delayed manifestation of pluripotent cell morphogenesis. This may further lead us to re-think whether bigerminal choristomas in the naso-oropharynx could be neoplastic—a proposition supported by earlier researchers [16] like Cadman and Kintzen [20], and by the ongoing controversy on nosology of the complex germ-layer lesions. Interestingly, in spite of increased reporting, the number of adult patients has still remained low (Fig. 4, 5), indicating that this age-group is affected quite exceptionally.

Graphical representation of the reporting of male patients (the blue rhomboids) and adult patients (the red squares) with bigerminal naso-oropharyngeal choristomas with time. The blue line shows the moving average reporting of the male patients, and the red line that of the adults. It is evident that with increasing documentation, the number of male patients is consistently on the rise, especially in the last 7 years. The impression is not so clear for the adult patients due to less number of cases, but there has been 2 cases reported in 2013, the highest in the last 25 years

The female preponderance

Bigerminal choristomas of the naso-oropharynx have a definite female preponderance that still remains unexplained. Most researchers have stated the female:male ratio as 6:1 [9, 21], though it was put at 8 in the review by Kalcioglu et al. [22]. However, we found it to be 3.5—a significant deviation from earlier reports [Table 2]. Interestingly, of the 16 male patients in the last 25 years, 10 were reported within the last 7 years itself (Fig. 4). Therefore, the female preponderance as believed presently is a definite overestimation, and this could be explained from the steady rise in documentation especially in the recent years (Fig. 5). Ahmadi et al. [23] had searched for parthenogenesis to explain the origin of teratomatous lesions, but human parthenogenesis is a poorly understood, inadequately studied topic and seems not a suitable explanation for the female preponderance.

Presentation and site of involvement—the role of endoscopy

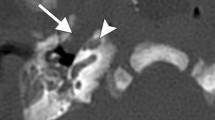

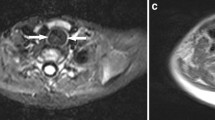

Within the naso-oropharynx and oral cavity, the lateral nasopharyngeal wall is the commonest subsite of bigerminal choristomas (29.49 %), followed by the tonsils/faucial pillars (~18 %) (Table 5). With the left side being 6.5 times more commonly involved than the right, they either present as visible masses, or produce symptoms due to mass effect causing respiratory obstruction (50 %), dysphagia (24.36 %), or both (~19 %) (Table 4). Most symptoms were relieved on excision of the mass, but proper diagnosis of hairy polyp in a child presenting with respiratory distress often becomes challenging. A recent study by Koike et al. [24] has shown that hairy polyps present with respiratory obstruction in 52.5 % cases and with dysphagia in 36 % cases, comparable to our findings. Interestingly, lesions ≤3 cm were more prone to produce symptoms because they were more liable to be missed by routine clinical examinations [24]. These lesions are not life-threatening per se, but, at least in two instances, delayed diagnosis has led to grave consequences like psychomotor retardation in older age due to cerebral hypoxia [24, 25]. Knowledge of the disease entity and a high index of suspicion would guide a clinician to search for a cause with endoscopy and imaging in a child with refractory and persistent respiratory insufficiency when other causes have been ruled out. Telescopes not only help in delineating the origin in anatomic details (Fig. 6a, b), they also ensure complete removal [26], and thereby prevent recurrences [27]. Endoscopy for excision of such masses was first described by Roh in 2004 [28], and the present consensus in published texts suggests that it is the gold standard procedure to diagnose as well as treat hairy polyps in the head-neck area. A combined naso-endoscopic and trans-oral approach has recently been emphasized by Agrawal et al. for surgical management of similar lesions [29], and it follows that careful flexible nasopharyngoscopy in a child in distress should be made considering the possibility of a nasopharyngeal mass, possibly a hairy polyp, causing upper airway obstruction.

Eustachian tube dermoids: developmental error in the pharyngeal arch apparatus as a feasible explanation of naso-oropharyngeal choristoma

Nicklaus et al. [30] in 1991 first reported a hairy polyp originating from Eustachian tube and growing outward into the nasopharynx that was removed by trans-oral route. It appears that with widespread use of telescopes, many of these bigerminal choristomas of the lateral nasopharyngeal wall could well be found originating from Eustachian tube. This review shows that Eustachian tube hairy polyps constitute almost two-thirds of those arising from the lateral nasopharyngeal wall (Table 5), yet it seems such incidences until recently went grossly underreported. Recent reviews by Muzzi et al. [2] and Nalavenkata et al. [26] establish Eustachian tube lesions, including teratomas and dermoid/hairy polyp complex, as a new group of “emerging disease entity”. The Eustachian tube presently forms a distinctive anatomic and embryologic landmark in the classification of head-neck dermoids [2, 31].

Hairy polyps do not represent any syndromic disorder [4], but are occasionally associated with cleft palate, uvular agenesis, ankyloglossia, facial hemihypertrophy, low-set ears, osteopetrosis, hypospadias, left carotid artery atresia, agenesis of external auricle, bifurcation of tongue and branchial arch sinuses [4–6, 13, 32, 33]. There have been no such reports in adults—but they are of interest for some possible explanation of their origin. Of particular importance are the branchial arch anomalies often associated with hairy polyps of the naso-oropharynx [5, 32]. They support the ontogenetic principles laid down by Brown-Kelly [7], New and Erich [34], Sexton [35] and Burns et al. [5] (Table 4) that bigerminal choristomas in the head-neck are related to the development of the first and second pharyngeal arches. The proposition of Eustachian tube as the putative origin of bigerminal choristomas is supported by the speculation of their embryologic origin in relation to the pharyngeal arches.

During the fourth week of development, the dorsal part of the first and second arch endoderm (the pharyngeal pouch) join to form the tubotympanic recess, and with mesodermal interposition, form the middle ear cavity and Eustachian tube [36, 37]. Middle ear and mastoid account for about 15.38 % of the hairy polyps (Table 5), including one recurrence in the lateral nasopharyngeal wall [26]. Prior to Nicklaus et al., there were few reports of hairy polyps limited within the Eustachian tube that were removed by simple or modified radical mastoidectomy [31]. Overall, the middle ear cleft constitutes about 23 % of cases [Tables 2, 5]. Thus, with growing evidence of Eustachian tube as the predominant subsite for bigerminal choristomas in the nasopharynx [Fig. 6a, b], the probability of such lesions being developmental errors during pharyngeal arch morphogenesis is strengthened. This is further supported by the fact that the tonsils and faucial pillars, the commonest subsite in the oropharynx (~18 %) [Table 5], also develop from the ventral aspect of the second pharyngeal pouch.

Laterality and molecular control of pharyngeal arch morphogenesis

For reasons unknown, the left side has been found to be 6.5 times more commonly involved irrespective of the site of origin. Study on the molecular control of the development of head and neck shows that the first and second pharyngeal arches are populated by migrating NCCs from segmented regions of rhombencephalon (the rhombomeres; R1–8) in a pre-destined, programmed and regulated manner [3, 36], carrying genetic signals through the Hox and Otx2 [36] genes that convey positional information to the respective pharyngeal arches and the ultimate organogenesis of face. Expression of the Hox genes is further regulated by the sonic hedgehog (shh) genes which determine the left–right asymmetry during morphogenesis. The complex interplay between the shh gene products (coding for preferential left-sided expression [38]) and Hox in regulating the epithelial–mesenchymal interaction at the pharyngeal arches that could account for the lateral nasopharyngeal wall as the predominantly involved site, needs further exploration in determining the left-predominance of such lesions.

Expanding domain of the “teratoma family”—is naso-oropharyngeal choristoma a neoplasia or a developmental error?

Hairy polyps are diagnosed by history, clinical examination and histopathology. With the use of diagnostic endoscopy, imaging often becomes non-contributory, limited to identifying the extent and bony breach (ultrasonography, CT scan), and tissue composition (“fat within the mass”) and intracranial extension (MRI) [4, 30, 39, 40]. Histopathology typically reveals ectodermal and mesodermal derivatives [Fig. 2], and grossly the surface might not always be hair-covered [41, 42]. Though characteristically bigerminal, there are reports where authors have referred them as teratoma, teratoid, or more specifically, bigerminal “teratomas” [13, 43, 44]. In contrast, they might actually originate from single germ-cell lineage, the neuroectoderm, having major contribution to the head-neck mesenchyme (the ectomesenchyme) [35]. It therefore appears that the rigidity of the classification system of complex germ-cell lesions has been acceptably approached with leniency. Thus, though hairy polyps more closely resemble dermoids (Arnold’s classification [1]), they have often been referred to as “tumors”, suggesting their association with teratoma, a true neoplasia [4, 10, 13, 22, 45]. With few such reports in previously asymptomatic adults, the theory of neoplasia might be pertinent.

However, unlike teratoma, hairy polyps are slow-growing [46, 47] with no malignant transformation [27], leading authors like Vaughan et al. [32] and Seng et al. [48] comment that they should not be considered a primitive teratoma but strictly as developmental malformations. Similar views were shared by Heffner et al. who proposed that cartilaginous tissue plates in such lesions morphologically resembled fetal pinna, but were unlike the orientation seen in teratomas [46]. Yet in adults, they arise in areas so long unaffected in their life, and the theory of developmental malformation is probably inadequate to implement. Possibilities of focal neoplasm thus cannot be ruled out; Green and Pearl, while describing one of the five adult cases of hairy polyp mentioned in this review, have stated them as “neoplastic” [10], while Ferlito and Devaney [49] have placed them under the family of “benign teratoma”.

With the current evidence, the definition of teratoma is seemingly experiencing a paradigm shift: a “histologically divergent differentiation” from the conventional “trigerminal” lesion [1] to a mass composed of any two germ layers [13, 50, 51]. The complex germ-cell lesions hence belong to a larger “teratoma family”. Hairy polyp has therefore been denoted as a “primitive form of teratoma” by Karabekmez et al. [52], or as a subgroup of benign teratomas [53]. Weaver et al. [54] have even defined teratoma as a tumor of multiple tissues non-indigenous to their site of origin, emphasizing on the aberrant location rather than on composition. A growing group of researchers consequently are of the opinion that these bigerminal lesions of the naso-oropharynx should better be called choristomas—the heterotopic cell-rests [5, 16, 35, 42, 45, 48, 55, 56]. Though the choristoma/hamartoma group is essentially non-neoplastic, and not much is known about their origin as well, this alternative approach of classification might address the existing controversies related to the genesis of the complex germ-layer lesions.

Strengths and limitations of the review

The present review, the largest and the most comprehensive till date, deals elaborately with the clinics and present-day management of hairy polyps. It provides an up-to-date knowledge regarding the nosology and embryogenesis by analyzing the theories of origin, re-establishing the relationship between hairy polyps, the Eustachian tube system, and the development of the first two pharyngeal arches. Furthermore, the importance of a high index of suspicion of the possibility of a choristomatous mass obstructing the airway of a child in distress has been underlined. However, the review has its limitations. Non-English articles have been excluded, and being restricted to a given anatomic site, rare areas of involvement like the nose [57] could not be considered. Accordingly, time-trend of the reported cases would have been more accurate had all the cases of hairy polyps in the head-neck region be included. However, the non-English texts did not contribute significantly to the case bulk. Also, the naso-oropharynx, oral cavity and the middle ear system as an embryologically linked unit formed the most representative area for hairy polyps in the head-neck region. Therefore, the time-trend estimated should provide an unbiased view of the reporting of cases.

Conclusions and implications for practice

Naso-oropharyngeal hairy polyps mostly present in female neonates predominantly with respiratory obstruction and feeding difficulties, and with a left-sided predilection. They can be life-threatening if diagnosed late, especially when smaller. A child with refractory respiratory distress and difficulty in feeding where all possible causes have been excluded should be specifically looked for a hairy polyp in the naso-oropharynx. With increasing reports in recent years in the head-neck region, it appears that it is not as uncommon as generally believed. Flexible nasopharyngoscopy would be the best modality for estimating the size and localizing the mass. Fortunately, they have no malignant potential and symptoms are cured on surgical removal. Proper understanding of their biologic behavior requires in-depth study of embryology and molecular genetics, but an elementary idea is essential for the clinicians-in-practice, especially about their relationship with the development of the pharyngeal arches. This is because children with hairy polyps often present with pharyngeal arch anomalies, apart from other congenital stigmata. Their occurrence in adults is extremely rare and perplexing, thus might be confused with the commoner entities. The concept of focal neoplasia might be relevant, apart from the conventional theories of developmental malformations, to explain the occurrence of hairy polyps. In this review, we have highlighted the clinical characteristics of bigerminal choristomas of the naso-oropharynx and discussed about their origin and morphogenesis, as understanding their clinico-embryologic profile would help clinicians in timely diagnosis and management of similar lesions.

References

Arnold J (1870) A case of congenital composite lipoma of the tongue and pharynx with perforation of the skullbase [in German]. Virchows Archiv fur Pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und fur Klinische Medizin 50:482–516

Muzzi E, Cama E, Boscolo-Rizzo P et al (2012) Primary tumors and tumor-like lesions of the eustachian tube: a systematic review of an emerging entity. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 269(7):1723–1732

Minoux M, Antonarakis GS, Kmita M et al (2009) Rostral and caudal pharyngeal arches share a common neural crest ground pattern. Development 136:637–645

Kelly A, Bough D Jr, Luft JD et al (1996) Hairy polyp of the oropharynx: case report and literature review. J Pediatr Surg 31:704–706

Burns BV, Axon PR, Pahade A (2001) ‘hairy polyp’ of the pharynx in association with an ipsilateral branchial sinus: evidence that the ‘hairy polyp’ is a second branchial arch malformation. J Laryngol Otol 115:145–148

Haddad J Jr, Senders CW, Leach CS et al (1990) Congenital hairy polyp of the nasopharynx associated with cleft palate: report of two cases. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 20:127–135

Brown-Kelly A (1918) Hairy or dermoid polyp of the pharynx and nasopharynx. J Laryngol Otol 33:65–70

Budenz CL, Lesperance MM, Gebarski S (2005) Hairy polyp of the pharynx obscured on physical examination by endotracheal tube, but diagnosed on brain imaging. Pediatr Radiol 35:1107–1109

April MM, Ward RF, Garelick JM (1998) Diagnosis, management and follow-up of congenital head and neck teratomas. Laryngoscope 108:1398–1401

Green VS, Pearl GS (2006) A 24-year-old woman with a nasopharyngeal mass. Arch Pathol Lab Med 130:e33–e34

Cerezal L, Morales C, Abascal F et al (1998) Magnetic resonance features of nasopharyngeal teratoma (hairy polyp) in adult. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 107:987–990

Franco V, Florena AM, Lombardo F et al (1996) Bilateral hairy polyp of the oropharynx. J Laryngol Otol 110:288–290

Tariq MU, Din NU, Bashir MR (2013) Hairy polyp, a clinicopathological study of four cases. Head Neck Pathol. doi:10.1007/s12105-013-0433-4 (Epub ahead of print)

Planas S, Ferreres JC, Ortega A et al (2009) Association of congenital hypothalamic hamartoma and hairy polyp. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 33:609–610

Unal T, Erturk S (1994) Cartilaginous choristoma of the gingiva. Report of two cases; review of the literature of both gingival choristomas and intraoral chondromas. Ann Dent 53:19–27

Cone BM, Taweevisit M, Shenoda S et al (2012) Pharynhgeal hairy polyps: five new cases and review of the literature. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 31:184–189

Calcaterra T (1969) Teratomas of the nasopharynx. Ann Otol rhinol laryngol 78:165–171

Nguyen LT, Laberge JM (2000) Teratomas, dermoids and other soft tissue tumors. In: Ashcraft KW (ed) Pediatric Surgery. Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 972–974

Resta L, Santangelo A, Lastilla G (1984) THe S. C. ‘hairy polyp’ or ‘dermoid’ of the nasopharynx (An unusual observation in older age). J Laryngol Otol 98:1043–1046

Cadman TA, Kintzen W (1963) Nasopharyngeal teratoma. Can Med Assoc J 88:666–667

Luna MA, Cardesa A, Barnes L et al (2005) Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumors. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D (eds) World Health Organization classification of tumors. IARC Press, Lyon, p 99

Kalcioglu MT, Can S, Aydin NE (2010) Unusual case of soft palate hairy polyp causing airway obstruction and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg 45:E5–E8

Ahmadi MS, Dalband M, Shariatpanahi E (2010) Oral teratoma (epignathus) in a newborn: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol 24:59–62. doi:10.1016/j.ajoms.2011.06.006

Koike Y, Uchida K, Inoue M (2013) Hairy polyp can be lethal even when small in size. Pediatr Int 55(3):373–376

van Haesendonck J, van de Heyning PH, Claes J et al (1990) A pharyngeal hairy polyp causing neonatal airway obstruction: a case study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 19:175–180

Nalavenkata S, Meller C, Forer M (2013) Dermoid cysts of the Eustachian tube: A transnasal excision. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 77:588–593 review

Chang SS, Halushka M, Meer JV et al (2008) Nasopharyngeal hairy polyp with recurrence in the middle ear. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 72:261–264

Roh JL (2004) Transoral endoscopic resection of a nasopharyngeal hairy polyp. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 68:1087–1090

Agrawal N, Kanabar D, Morrison GA (2009) Combined transoral and nasendoscopic resection of an eustachian tube hairy polyp causing neonatal respiratory distress. Am J Otolaryngol 30:343–346

Nicklaus PJ, Forte V, Thorner PS (1991) Hairy polyp of the eustachian tube. J Otolaryngol 20(4):254–257

Arcand P, Abela A (1985) Dermoid cyst of the eustachian tube. J Otolaryngol 14:187–191

Vaughan C, Prowse SJ, Knight LC (2012) Hairy polyp of the oropharynx in association with a first branchial arch sinus. J Laryngol Otol 126(12):1302–1304

Desai A, Kumar N, Wajpayee M et al (2012) Cleft palate associated with hairy polyp: a case report. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. doi:10.1597/11-231 (Epub ahead of print)

New GB, Erich JB (1937) Dermoid cysts of the head and neck. Surg Gynecol Obstet 65:48–55

Sexton M (1990) Hairy polyp of the oropharynx: a case report with speculation on nosology. Am J Dermatopathol 12(3):294–298

Sadler TW (2012) Head and Neck. Langman’s Medical Embryology 12th edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Philadelphia. pp 264–85

Gourin CG, Sofferman RA (1999) Dermoid of the eustachian tube. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 120:772–775

Tabin CJ (2006) The key to left-right asymmetry. Cell 127:27–32

Kochanski SC, Burton EM, Seidel FG et al (1990) Neonatal nasopharyngeal hairy polyp: CT and MR appearance. J Comput Assist Tomogr 14(6):1000–1001

Kraft JK, Knight LC, Cullinane C (2011) US and MRI of a pharyngeal hairy polyp with pathological correlation. Pediatr Radiol 41:1208–1211

Kollias SS, Ball WS Jr, Prenger EC et al (1995) Dermoids of the Eustachian tube: CT and MR findings with histologic correlation. AJNR Am L Neuroradiol 16(4):663–668

Erdogan S, Tunali N, Canpolat T et al (2004) Hairy polyp of the tongue: a case report. Pediatr Surg Int 20:881–882

Yilmaz M, Ibrahimov M, Ozturk O (2012) Congenital hairy polyp of the soft palate. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 76:5–8 review

Delides A, Sharifi F, Karagianni E et al (2006) Multifocal bigerminal mature teratomas of the head and neck. J Laryngol Otol 120(11):967–969

Mirshemirani A, Khaleghnejad A, Mohajerzadeh L et al (2011) Congenital nasopharyngeal teratoma in a neonate. Iran J Pediatr 21(2):249–252

Heffner DK, Thompson LD, Schall DG et al (1996) Pharyngeal dermoids (“hairy polyps”) as accessory auricles. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 105:819–824

Mitchell TE, Girling AC (1996) Hairy polyp of the tonsil. J Laryngol Otol 110:101–103

Seng S, Kieran SM, Vargas SO et al (2013) Caught on camera: hairy polyp of the posterior tonsillar pillar. J Laryngol Otol 127(5):528–530

Ferlito A, Devaney KO (1995) Developmental lesions of the head and neck: terminology and biologic behavior. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 104:913–918

Steinbach TJ, Reischauer A, Kunkemöller I et al (2004) An oral choristoma in a foal resembling hairy polyp in humans. Vet Pathol 41:698–700

Smirniotopoulos JG, Chiechi MV (1995) Teratomas, dermoids, and epidermoids of the head and neck. Radiographics 15:1437–1455

Karabekmez FE, Duymaz A, Keskin M et al (2009) Reconstruction of a “double pathology” on a soft palate”: hairy polyp and cleft palate. Ann Plast Surg 63(4):393–395

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD et al (2007) The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 114:97–109

Weaver RG, Meyerhoff WI, Gates GA (1976) Teratomas of the head and neck. Surg Forum 27:539–544

Jarvis SJ, Bull PD (2002) Hairy polyps of the nasopharynx. J Laryngol Otol 116:467–469

Simoni P, Wiatrak BJ, Kelly DR (2003) Choristomatous polyps of the aural and pharyngeal regions: first simultaneous case. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 67:195–199

White LJ, Shehata BM, Rajan R (2013) Hairy polyp of the anterior nasal cavity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. doi:10.1177/0194599813506527 September 25 (E-pub ahead of print)

Lignitz S, Haug V, Siegmund B et al (2013) Intermittent dyspnea and cyanosis in a newborn caused by a hairy polyp. Pediatr Neonatol. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2013.07.009 November 4 (E-pub ahead of print)

Christianson B, Ulualp SO, Koral K et al (2013) Congenital hairy polyp of the palatopharyngeus muscle. Case Rep Otolaryngol. doi:10.1155/2013/374681

Puricelli E, Barra MB, Hochhegger B et al (2012) Hairy polyp on the dorsum of the tongue–detection and comprehension of its possible dynamics. Head Face Med 8: 19 (http://www.head-face-med.com/content/8/1/19; accessed on 10th May, 2013)

Zakaria R, Drinnan NRT, Natt RS et al (2011) Hairy polyp of the nasopharynx causing chronic middle ear effusion. BMJ Case Rep doi:10.1136/bcr.08.2010.3244 (http://casereports.bmj.com/content/2011/bcr.08.2010.3244.full; accessed on 23rd September, 2012)

Wang JL, Hou ZH, Chen L et al (2011) Combined application of oto-endoscopes and nasal endoscopes for resection of dermoid tumor in eustachian tube. Acta Otolaryngol 131:221–224

Russo E, Vaknine H, Roth Y (2010) Dermoid of the nasopharynx: an unusual finding in an older child. Ear Nose Throat J 89(4):162–163

Saliba I, El Khatib N, Quintal MC et al (2010) Tonsillar hairy polyp. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 39:E67–E69

Fawziyah A, Linder T (2010) Oropharyngeal hairy polyps: an uncommon cause of infantile dyspnea and dysphagia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 143:706–707

Walker P (2008) Dilated Eustachian tube orifice after endoscopic removal of hairy polyp. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 139:162–163

Gambino M, Cozzi DA, Aceti MG et al (2008) Two unusual cases of pharyngeal hairy polyp causing intermittent neonatal airway obstruction. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 37(761–2):35

Jang SH, Min KW, Na W et al (2008) An unusual meningothelial element in a hairy polyp of the hard palate. Korean J Pathol 42:311–313

Hemant M, Ashok BS, Shantilal PS et al (2007) Hairy polyp of the oropharynx. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 5:602–603

Shvidler J, Cable BB, Sheridan M (2007) Hairy polyp in the oropharynx of a 5-week-old infant with sudden-onset respiratory distress. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 136:491–492

Yossuck P, Williams HJ, Polak MJ et al (2007) Oropharyngeal tumor in the newborn: a case report. Neonatology 91:69–72

Baek SJ, Kim SC, Kim DI et al (2005) Hairy (dermoid) cyst originating from the eustachian tube. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 131(823):826–827

Kiroglu AF, Kutluhan A, Bayram I et al (2004) Reconstruction of congenital midpalatal hairy polyp. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 42:72–74

Karagama YG, Williams RS, Barclay G et al (2003) Hairy polyp of the oropharynx in a newborn: a case report. Rhinology 41:56–57

De Caluwe´ D, Kealey SM, Hayes R (2002) Autoamputation of a congenital oropharyngeal hairy polyp. Pediatr Surg Int 18:548–549

Phansalkar M, Sulhyan K, Muley P et al (2000) Hairy polyp of nasopharynx —a case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 43:355–356

Downs BW, Shores CG, Drake AF (2000) Choristoma of the nasopharynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 123:523

Ruah CB, Cohen D (1999) Sade´ J. Eustachian tube teratoma and its terminological correctness. J Laryngol Otol 113:271–274

Chakravarti A, Vishwakarma SK, Arora VK et al (1998) Dermoid (hairy polyp) of the nasopharynx. Indian J Pediatr 65:473–476

Kieff DA, Curtin HD, Limb CJ et al (1998) A hairy polyp presenting as a middle ear mass in a pediatric patient. Am J Otolaryngol 19:228–231

Walsh RM, Philip G, Salama NY (1996) Hairy polyp of the oropharynx: an unusual cause of intermittent neonatal airway obstruction. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 34:129–134

Olivares-Pakzad BA, Tazelaar HD, Dehner LP et al (1995) Oropharyngeal hairy polyp with meningothelial elements. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 79:462–468

Boedts D, Moerman M, Marquet J (1992) A hairy polyp of the middle ear and mastoid cavity. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg 46:397–400

Vrabec JT, Schwaber MK (1992) Dermoid tumor of the middle ear. Case report and literature review. Am J Otol 13:580–581

Aughton DJ, Sloan CT, Milad MP et al (1990) Nasopharyngeal teratoma (‘hairy polyp’), Dandy-Walker malformation, diaphragmatic hernia, and other anomalies in a female infant. J Med Genet 27:788–790

Kainz J, Kobierski S, Jakse R et al (1990) Choristoma of the soft palate. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 247(4):264–266

McShane D, el Sherif I, Doyle-Kelly W et al (1989) Dermoids (‘hairy polyps’) of the oro-nasopharynx. J Laryngol Otol 103(6):612–615

Eggston AA, Wolff D (1947) Histopathology of ear, nose and throat. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore

Schuring AG (1964) Accessory auricle in the nasopharynx. Laryngoscope 74:111–114

Badrawy R, Fahmy SA, Taha AM (1973) Teratoid tumours of the nasopharynx. J Laryngol Otol 87:795–799

Holt GR, Holt JE, Weaver RG (1979) Dermoids and teratomas of the head and neck. Ear Nose Throat J 58:520–531

Acknowledgments

We thank Mahmut T Kalcioglu, MD, Professor, Istanbul Medeniyet University, Turkey; Bahig M Shehata, MD, Professor of Pathology and Pediatrics, Emory University School of Medicine, Georgia, USA; and Alexander Delides, MD, PhD, Lecturer, Athens Medical Center, Greece, for their kind advices and helping us with literature review, and also to Sunny Nalavenkata, MBBS, Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, Australia, and Enrico Muzzi, MD, Audiology and ENT Unit, Department of Pediatrics, Institute for Maternal and Child Health, IRCCS “Burlo Garofalo”, Trieste, Italy, for supporting us with literature search and moral inspiration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dutta, M., Roy, S. & Ghatak, S. Naso-oropharyngeal choristoma (hairy polyps): an overview and current update on presentation, management, origin and related controversies. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 272, 1047–1059 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-014-3050-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-014-3050-2