Abstract

Otogenic skull base osteomyelitis (SBO) of fungal etiology is a very rare but life-threatening complication of inflammatory processes of the ear. The authors present a case of otogenic SBO caused by Aspergillus flavus in a 65-year-old man with a fatal course. Because of the encountered difficulties with the proper diagnosis and treatment, the authors reviewed the literature on the subject.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Otogenic skull base osteomyelitis (SBO) is a rare but serious complication of inflammatory processes of the ear, posing great diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties. Otogenic SBO was first described in 1959 by Meltzer and Kelemen [25]. In 1968, Chandler introduced a term of malignant otitis externa referring to the aggressive, destructive inflammatory process caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, originating in the external auditory canal and having a tendency to spread to the skull base. The disease manifests itself in cranial nerves palsies and often leads to death [7]. The etiological factor is in 99.2% P. aeruginosa [2, 10], and in the remaining cases other microorganisms such as Staphylococcus aureus, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella oxytocyta and fungi [15, 21, 27, 29, 38]. Typical otogenic SBO of bacterial etiology is a result of the inflammatory process of the external ear and generally develops in people over 60 with uncontrolled diabetes. The points of entry of mycotic infections may be both the external ear and the middle ear (acute or chronic otitis media), and the predisposing factors are immunodeficiency (most often AIDS and blood proliferative diseases) [29, 38]. Petrak et al. were the first to describe a case of SBO in the course of invasive, mycotic (Aspergillus) otitis externa in 1985 [30]. Since then only 38 cases of invasive mycotic inflammation of the temporal bone with or without the involvement of the skull base have been described in the English-language literature. Having in mind the above described diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties the authors present their case of this severe disease together with the literature review.

Case report

A 65-year-old man was admitted to hospital having suffered from acute headaches of the left side accompanied by vertigo, disturbed balance, nausea, difficulty in swallowing and choking for 3 months. He had also been suffering from periodic otorrhea from the left ear and some loss of hearing for about 3 years. He had been hospitalized twice in the previous 2 months in other ENT department where recurrent acute otitis media had been diagnosed and conservative treatment had been ordered (intravenous antibiotics and paracentesis). The case history revealed chronic alcohol abuse, type 2 diabetes mellitus (treated with oral hypoglycemic drugs for several years) and arterial hypertension. On admission his general condition was medium severe, the patient was afebrile. On ORL examination left external auditory canal showed no signs of inflammation or granulation. Tympanic membrane was thickened, without visible anatomic structure, movable. Fistulous test was negative. His right ear was without any deviation. Tuning fork tests were consistent with a left conductive hearing loss, which was confirmed by 40- to 55-dB hearing loss on pure tone audiometry. Additionally, a sensorineural hearing loss up to 40 dB for 4 kHz in the right ear was revealed. The examination showed a peripheral nerve VII palsy (4/6 in House-Brackmann scale) and palsy of cranial nerves IX, X, XI, XII on the right side. Meningeal symptoms were negative. Laboratory tests showed increased values of C-reactive protein of 84 mg/l. The level of serum glucose was 187 mg%. Diagnostic paracentesis was performed and plethoric secretion was sucked out. However, pathogens were cultured neither from this secretion nor from the left auditory canal smears (examination repeated three times). The patient was tested for tuberculosis, Wegener’s granuloma and HIV, and the results were negative.

Scintigraphic examination of bones showed an increased marker uptake in the left temporal bone projection. MRI detected extensive infiltration within the pyramid of the temporal bone and middle skull base fossa, in the vicinity of the clivus, extrameningeally. It was spreading to the right side and got more intense with contrast medium. The image showed an inflammatory process (Fig. 1).

Both clinical and additional examination results led to the diagnosis of otogenic SBO. Taking into consideration bad condition of the patient, further invasive diagnostic procedures (mastoidectomy) were abandoned. Empiric therapy with intravenous antibiotics aimed at P. aeruginosa was employed: ceftazidime (Fortum®), dose 2 × 1.0 g; ciprofloxacin (Ciprinol®), dose 2 × 0.2 g. Hyperbaric oxygenation (HBO, altogether 16 exposures) in the National Center of Hyperbaric Medicine in Gdynia was ordered too. Antibiotic treatment was supplemented with intensive insulinotherapy and antifungal protection (ketoconazole 0.2 g/24 h).

Despite the applied therapy, the patient’s condition did not improve and after 18 days there was a violent progression of the disease—nerves III, IV and VI palsies on the left side together with quantitative disorder of consciousness and worsening of patient’s general condition. Repeated MRI examination disclosed significant progression of the disease with infiltration caused by the inflammatory process in the left cavernous sinus, bulb of the interior jugular vein, parapharyngeal space and penetration to the nasopharynx as well as contraction and loss of flow in the internal carotid artery. The infiltration got more intense with contrast medium, with visible dura enhancement in the area of the temporal lobe and ponto-cerebellar angle. There were no signs of increased intracranial pressure (Fig. 2).

Lumbar puncture disclosed reactive cerebrospinal fluid with no pleocytosis. First, in repeated bacteriological tests (smears from the left auditory canal) isolated colonies of Aspergillus spp. were cultured. Next examination revealed presence of Aspergillus flavus. Suspected systemic mycosis was confirmed serologically (titer of antibodies against A. flavus 1:320, Aspergillus antigen negative). Because of patient’s severe condition (very high risk of surgery) and the isolation of the etiological factor confirmed by serological examination, the previously planned diagnostic mastoidectomy was abandoned again.

Liposomal Amphotericine B (Ambisome®) was administered intravenously, in increasing dose from 1 to 3 mg/kg/24 h and orally—itraconazole (Orungal®) 2 × 0.2 g. Despite the applied therapy lasting 30 days, further worsening of patient’s general condition was observed—respiratory failure demanding mechanical ventilation, rises of systolic blood pressure to 250 mmHg, arrhythmia, heavy electrolytic disturbances and changes in neurologic status—deep coma, right-sided hemiparesis and right nerve VI palsy. The patient died on the 53rd day of hospitalization.

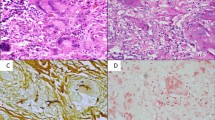

Post-mortem examination confirmed the clinical diagnosis of fungal (Aspergillus), invasive, otogenic SBO of the left side. The left temporal bone and lateral skull base were completely destructed by infiltration containing large amounts of yellowish, thick pus, which on histological examination revealed numerous septate branching fungal hyphae, consistent with Aspergillus. It disclosed fungal meningitis in the region of the left temporal lobe with some infiltration of cavernous sinus and the spread of the inflammatory process to the cerebral tissue. The autopsy also showed some features of endosepsis with the presence of fungal pulmonary embolism as well as changes characteristic of alcoholic liver disease.

Discussion

There are four potential routs of infection for invasive temporal bone and lateral SBO: from the external ear or, in the course of acute or chronic otitis media, via tympanic cavity (tympanogenic), meningogenic (in fungal meningitis, via internal auditory canal), from the Eustachian tube and hematogenic [17, 34, 39]. Extremely rare lateral SBO follows paranasal sinus infections [24]. Fungal infection usually develops primarily within the middle ear (tympanic cavity or mastoid process of the temporal bone) [37–39, 42]. In our patient the rout of entry of aspergillosis was most probably this area (recurrent acute otitis media treated with wide-spectral antibiotics) [31–33].

Table 1 presents a comparison of 40 cases of invasive mycoses of the temporal bone and lateral skull base. The dominant pathogen was Aspergillus fumigatus—19 pts, then A. flavus—10 pts, and significantly less frequent other fungi (Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus without determination of species, Pseudallescheria boydii, Scedosporium apiospermum, Malassezia sympodialis, Lecythophora hoffmannii, Candida ciferri). We found it odd that no Mucor infection was found in this group.

The predisposing factors in invasive fungal mycoses are found to be primary and acquired immunodeficiency (AIDS, neutropenia, leukemias), malignant neoplasms and their treatment (irradiation, chemotherapy), the use of steroids and wide-spectral antibiotics, “graft versus host” disease, systemic diseases and microflora disorders in the ear [26, 27, 35, 38, 42]. The comparison of invasive mycoses of the temporal bone and skull base presented in Table 1 shows that by far the most frequent risk factor was AIDS—15 patients, then—the disorder of leukocyte system (acute or chronic leukemia, neutropenia). Diabetes occurred in nine patients (in seven of them as the only risk factor). Chronic otitis media was found in four patients, secretory otitis media in one and recurrent acute otitis media in the described case. In one case, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and immunosuppressive treatment led to fungal invasive infection. No risk factor was found in five patients. In our case, apart from uncompensated diabetes, the major factor affecting the course of the disease seems to be alcoholism, since the suppressive influence of ethanol on the immunological system is generally known [19]. The age of the patient, unlike in the bacterial SBO, seems to be of secondary importance. In the 40 described cases, the age fluctuated from 6 to 85 years.

Many authors stress the need for prompt identification of the microorganisms involved in otogenic SBO [2, 3, 22, 24, 26, 37]. Cunningham et al. [10] are of the opinion that empiric treatment (directed against P. aeruginosa) of malignant otitis externa is unfounded, and prolonged antibiotic therapy should always be preceded by bacteriological examination. In case of mycoses, there are two problems: first, positive cultures are obtained only in 40% of aspergilloses (histopathologically confirmed) [3], and additionally, the value may be decreased by the prolonged use of antibiotic ear drops [15, 26]. Second, due to the frequent occurrence of saprophytic fungi in the external auditory canal, cultivation of Aspergillus does not justify the diagnosis of invasive mycosis. However, such examination result should not be disregarded and repeated smears and histopathological examination should be carried out [2, 17, 22]. Serological diagnostics of systemic mycoses is of limited value in immunocompromised patients since seroconversion occurs only in 35% of such patients [3].

To correctly diagnose and establish the proper anti-fungal treatment in case of non-diagnostic cultures and lack of improvement or progression of the disease, it is necessary to obtain material for histopathological and microbiological examination that may be acquired by mastoidectomy [10, 26]. Histopathological material obtained by mastoidectomy allows not only to confirm invasive mycosis but also to rule out the neoplastic growth or granuloma [15, 22, 29, 38, 41]. On the other hand, Kountakis et al. recommend performing a diagnostic mastoidectomy after 4 weeks, if the applied treatment does not bring any improvement [22]. Considering the described case and difficulties to discover the etiology of lateral skull base osteomyelitis, the authors state, that diagnostic mastoidectomy should not be postponed longer than 2 weeks, if empiric therapy is not effective. In case of very extensive osteomyelitis and bad general condition of a patient, thus with high risk of rapid progression of the disease, initial “aggressive” diagnostics could be considered.

Classic invasive (caused by P. aeruginosa) otitis externa was divided into three stages (I—the process limited to the soft tissues and cartilage of the external auditory canal, II—limited SBO, III—diffuse infiltration of the skull base) [29]. However, this division has no practical use in case of mycoses because of frequently occurring involvement of the middle ear area. Chen et al. [9] proposed an interesting classification of fungal infections of the ear and temporal bone infections on the base of classification of paranasal sinuses mycoses. They divided mycotic infections into four types depending on the extension of the inflammation process and the presence of facial nerve palsy including their proper treatment (Table 2).

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, treatment of invasive fungal infections of the temporal bone and skull base consists of three parts: compensation of immunological deficiency and/or predisposing disease (AIDS, diabetes), administration of anti-fungal agents and aggressive surgical debridement [1, 2, 39, 42]. Grandis et al. [15] recommend prolonged (above 12 weeks) administration of Amfotericin B, best in a liposomal form, since it is less nephrotoxic (which is important for a diabetic patient). According to the data from Table 1 most of the cases were treated with Amfotericin B intravenously with a positive response in 21 of 40 patients and with a failure in 8 and itraconazole was administered as an additional agent or in a prolonged therapy. In three cases, itraconazole was used as the only antifungal drug (in one case together with HBO) and the result in two patients was full recovery (the follow up in the third patient was unavailable) [13, 16, 39]. One case of Aspergillus mastoiditis was successfully treated with new broad spectrum antifungal agent—voriconazole [1]. Therapeutic mastoidectomy is recommended, according to Finer et al. [13], when persistent mycosis (despite intravenous and/or oral treatment) is suspected. Other authors reported, that only a wide cortical mastoidectomy with opening and clearing of the mastoid antrum allows for local control of the disease [9, 28]. HBO against invasive mycosis of the temporal bone and skull base is not a generally accepted method of treatment, unlike in malignant otitis externa of P. aeruginosa etiology. Apart from our patient, this method was applied only in one case [16]. It was proved (mainly by in vitro tests) that hyperbaric oxygen had at least an inhibiting effect on fungi [16]. HBO, as an adjuvant method, is generally accepted in cases of osteomyelitis and the indication for its use are stages II and III of malignant otitis externa [11, 36]. According to the classification proposed by Chen et al. [9], in case of invasive mycoses of temporal bone and skull base, HBO should be used in stages III and IV and its use should be considered in stage II.

Involvement of cranial nerves in malignant, bacterial external otitis testifies to the extension of the process and is an unfavorable prognostic factor [24, 29, 34, 38]. Similar to P. aeruginosa, one of the endotoxins produced by Aspergillus shows neurotoxic activity [26]. Additionally, in mycoses of the temporal bone there is a great risk of sensorinervous deafness [28]. Among 40 cases of invasive mycoses of the temporal bone and skull base, isolated paresis/palsy of the facial nerve was dominant (about 70%). In four patients, other cranial nerves (IX–XII) were also involved. However, because of too small group of patients it is impossible to determine if the cranial nerves involvement is a significant prognostic factor [1–6, 8–10, 12–14, 16–18, 20, 22, 23, 26–28, 30–33, 35, 37, 39, 40, 42, 43].

According to Table 1 mortality due to invasive mycosis of the temporal bone and lateral skull base was about 27%. It should be mentioned that prognosis seems to depend more on the state of the immunity system than on the treatment applied [2, 27, 37, 42].

To summarize, invasive, fungal temporal bone and SBO occurs usually in immunocompromised patients (AIDS, blood diseases). Diabetes and age are of significantly less importance. The route of entry may be both the middle ear (tympanic cavity and mastoid process) and the external auditory canal. Prognosis depends not only on early, sometimes “aggressive” diagnosis (with obligatory microbiological and histopathological confirmation) and the therapy applied, but also (and perhaps mainly) on the condition of the immunological system of a patient. Fungal infection should be always considered part of the differential diagnosis of patients with lateral SBO, who are relatively immunocompromised and who do not respond to antibiotic treatment (in our opinion not longer than 2 weeks) regardless of cranial nerves involvement.

References

Amonoo-Kuofi K, Tostevin P, Knight JR (2005) Aspergillus mastoiditis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report. Skull Base 15(2):109–112

Bellini C, Antonini P, Ermanni S, Dolina M, Passega E, Bernasconi E (2003) Malignant otitis externa due to Aspergillus niger. Scand J Infect Dis 35:284–288

Bickley LS, Betts RF, Parkins CW (1988) Atypical invasive external otitis from Aspergillus. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 114:1024–1028

Bryce GE, Phillips P, Lepawsky M, Grible MJ (1997) Invasive Aspergillus tympanomastoiditis in an immunocompetent patient. J Otolaryngol 26:266–269

Busaba NY, Poulin M (1997) Invasive Pseudallescheria boydii fungal infection of the temporal bone. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 17:S91–S94

Chai FC, Auret K, Christiansen K, Yuen PW, Gardam D (2000) Malignant otitis externa caused by Malassezia sympodialis. Head Neck 22:87–89

Chandler JR (1968) Malignant external otitis. Laryngoscope 78(8):1257–1294

Chang CY, Schell WA, Perfect JR, Hulka GF (2005) Novel use of a swimming pool biocide in the treatment of a rare fungal mastoiditis. Laryngoscope 115(6):1065–1069

Chen D, Lalwani AK, House JW, Choo D (1999) Aspergillus mastoiditis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Otol 20:561–567

Cunningham M, Yu VL, Turner J, Curtin H (1988) Necrotizing otitis externa due to Apsergillus in a immunocompetent patient. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 114:554–556

Davis JC, Gates GA, Lerner C, Davis MG Jr, Mader JT, Dinesman A (1992) Adjuvant hyperbaric oxygen in malignant external otitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 118:89–93

Diop EM, Schachern PA, Paparella MM (1998) Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome with massive Aspergillus fumigatus infection. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 118:283–285

Finer G, Greenberg D, Leibovitz E, Leiberman A, Shelef I, Kapelushnik J (2002) Conservative treatment of malignant (invasive) external otitis caused by Aspergillus flavus with oral itraconazole solution in neutropenic patient. Scan J Infect Dis 34:227–229

Gordon G, Giddings NA (1994) Invasive otitis externa due to Aspergillus species: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 19:866–870

Grandis JR, Branstetter BF IV, Yu VL (2004) The changing face of malignant (necrotising) external otitis: clinical, radiological, and anatomic correlations. Lancet Infect Dis 4:34–39

Granstroem G, Hanner P, Edebo L, Fornander J (1990) Malignant external otitis caused by Pseudoalerscheria boydii. Treatment with hyperbaric oxygenation. In: Proceedings from the XVIth EUBS-meeting, Amsterdam, pp 41–49

Hall PJ, Farrior JB (1993) Aspergillus mastoiditis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 108:167–170

Hanna E, Hughes G, Eliachar I, Wanamaker J, Tomford W (1993) Fungal osteomyelitis of the temporal bone: a review of reported cases. Ear Nose Throat J 72:537–541

Happel KI, Nelson S (2005) Alcohol, immunosuppression, and the lung. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2(5):428–432

Harley WB, Dummer JS, Anderson TL, Goodman S (1995) Malignant external otitis due to Aspergillus flavus with fulminant dissemination to the lungs. Clin Infect Dis 20:1052–1054

Hern JD, Almeyda J, Thomas DM, Main J, Patel KS (1996) Malignant otitis externa in HIV and AIDS. J Laryngol Otol 110:770–775

Kountakis SE, Kemper JV Jr, Chang J, DiMaio DJM, Stiernberg CM (1997) Osteomyelitis of base of the skull secondary to Aspergillus. Am J Otolaryngol 18:19–22

Kuruvilla G, Job A, Mathew J, Ayyappan AP, Jacob M (2006) Septate fungal invasion in masked mastoiditis: a diagnostic dilemma. J Laryngol Otol 7:1–3

Malone DG, O’Boynick PL, Ziegler DK, Batnitzky S, Hubble JP, Holladay FP (1992) Osteomyelitis of the skull base. Neurosurgery 30:426–431

Meltzer PE, Kelemen G (1959) Pyocyaneous osteomyelitis of the temporal bone, mandible and zygoma. Laryngoscope 169:1300–1316

Menachof MR, Jackler RJ (1990) Otogenic skull base osteomyelitis caused by invasive fungal infection. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 102:285–289

Munoz A, Martinez-Chamorro E (1998) Necrotizing external otitis caused by Aspergillus fumigatus: computed tomagraphy and high resolution magnetic resonance imaging in an AIDS patient. J Laryngol Otol 112:98–102

Ohki M, Ito K, Ishimoto S (2001) Fungal mastoiditis in an immunocompetent adult. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 258:106–108

Patel SK, McPartlin DW, Philpoti JM, Abramovich MS (1999) A case of malignant otitis externa following mastoidectomy. J Laryngol Otol 113:1095–1097

Petrak RM, Pottage JC Jr, Levin S (1985) Invasive external otitis caused by Aspergillus fumigatus in an immunocompromised host (Letter). J Infect Dis 151:196

Phillips P, Bryce G, Shepherd J, Mintz D (1990) Invasive external otitis caused by Aspergillus. Rev Infect Dis 12:277–281

Reiss P, Hadderingh R, Schot LJ, Danner SA (1991) Invasive external otitis caused by Aspergillus fumigatus in two patients with AIDS. AIDS 5:605–606

Ress BD, Luntz M, Telischi FF, Balkany TJ, Whiteman ML (1997) Necrotizing external otitis in patients with AIDS. Laryngoscope 107:456–460

Rowlands RG, Lekakis GK, Hinton AE (2002) Masked psudomonal skull base osteomyelitis presenting with a bilateral Xth cranial nerve palsy. J Laryngol Otol 116:556–558

Shelton JC, Antonelli PJ, Hackett R (2002) Skull base fungal osteomyelitis in an immunocompetent host. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 126:76–78

Shupak A, Greenberg E, Hardoff R, Gordon C, Melamed Y, Meyer WS (1989) Hyperbaric oxygenation for necrotizing (malignant) otitis externa. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 115:1470–1475

Slack CL, Watson DW, Abzug MJ, Shaw C, Chan KH (1999) Fungal mastoiditis in immunocompromised children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 125:73–75

Sreepada GS, Kwartler JA (2003) Skull base osteomyelitis secondary to malignant otitis externa. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 11:316–323

Stanley RJ, McCaffrey TV, Weiland LH (1988) Fungal mastoiditis in the immunocompromised host. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 114:198–199

Strauss M, Fine E (1991) Aspergillus otomastoiditis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Otol 12:49–53

Subburaman N, Chaurasia MK (1999) Skull base osteomyelitis interpreted as malignancy. J Laryngol Otol 1113:775–778

Yao M, Messner AH (2001) Fungal malignant otitis externa due to Scedosporium apiospermum. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 110:377–380

Yates PD, Upile T, Axon PR, de Carpentier J (1997) Aspergillus mastoiditis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Laryngol Otol 111:560–561

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stodulski, D., Kowalska, B. & Stankiewicz, C. Otogenic skull base osteomyelitis caused by invasive fungal infection. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 263, 1070–1076 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-006-0118-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-006-0118-7