Abstract

A 5-week-old girl with inspiratory stridor is presented. No immediate cause of the stridor was found, but eventually a diagnosis of infantile hemangiopericytoma located in the rhinopharynx was made. After surgery all respiratory symptoms disappeared. Conclusion: Infantile hemangiopericytoma is a rare tumour of infancy and a very rare cause of inspiratory stridor in this age group. The mainstay of treatment is surgery. The overall prognosis is favourable but because of the unpredictable nature of the tumour, long-term follow-up is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hemangiopericytoma (HPC) is a rare soft tissue neoplasm. Only 5–10% of all cases occur in childhood. Almost half of these occur during the first year of life, and is defined as infantile HPC [2–3, 5, 8–9]. Location of infantile HPC in the rhinopharynx appears to be rare. Only one case of infantile HPC located in the rhinopharynx is reported earlier [10]. Below, another case of infantile HPC is presented as an unusual cause of early inspiratory stridor.

Case report

A 5-week-old girl was taken to hospital because of inspiratory stridor which began suddenly 2 days earlier in connection with regurgitation. Her previous history was unremarkable. At admission she was in good general condition apart from the respiratory distress. Temperature was a little above 38°C. Oxygen saturation was constantly above 95%. Blood tests showed total WBC count 15.6×109 cells/l, neutrophiles being 7.42×109 cells/l. Platelet count was 637×109 per litre. CRP was 22 mg/ml. PH was normal and pCO2 at the upper limit.

No infectious focus was found and suspicion of aspiration pneumonia was rejected. She preferred to lie with her head backwards. The degree of respiratory distress was fluctuating during the following days with short episodes of obstructive apnoea. The cause of the stridor was not found at the first examinations. The day after admission, however, a careful inspection of the oral cavity revealed a swollen mucous membrane around the uvula.

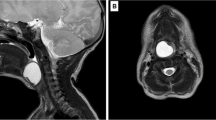

After her transfer to the regional university hospital, MRI showed a solid tumour in the rhinopharynx originating from the topside of the soft palate in close relation to the uvula. It measured 2×1.4×1.7 cm3 (Fig. 1). There were no signs of multicentricity.

Six days after admission the tumour was removed in toto. It was soft and mobile with a broad base on the superior side of the soft palate and a largest diameter of 1.8 cm.

Microscopic examination revealed a solid neoplasm with fascicular and focal nodular growth and a distinct staghorn-like vascular pattern (Fig. 2a). Some tendency to endovascular, nodular proliferation was seen (Fig. 2b). Small areas with necrosis interstitial haemorrhage and inflammatory cell infiltration were noted. The tumour cell population was composed of round to fusiform cells, often showing increased cellularity around the ectatic vascular channels. The tumour cell nuclei showed no pleomorphism, and were surrounded by cytoplasm with indistinct boundaries. The individual cell was, however, surrounded by reticulin (Fig. 2c). The number of mitoses varied, but focally more than 20 mitosis were counted per ten HPF, and the proliferation rate was estimated to 20–25% (Fig. 2d). Immunohistochemistry disclosed universal reaction for vimentin and focal staining for smooth muscle action (Fig. 2e) and CD34 (Fig. 2f). A large panel of other immunostains was employed, and among others negative stains for cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen, desmin, CD31, CD99, S-100, and bcl-2 were encountered. The microscopic findings were consistent with a consensus diagnosis of infantile hemangiopericytoma.

a Hematoxylin-eosin (original magnification 40×); b hematoxylin-eosin (original magnification 200×); c reticulin stain (original magnification 200×); d immunohistochemical stain for proliferation rate (MIB-1, original magnification 100×); e immunohistochemical stain for smooth muscle action (original magnification 100×); f immunohistochemical stain for CD34 (original magnification 100×)

Following the operation the respiratory problems disappeared completely. No adjuvant therapy was offered. Control MRI 3 months later disclosed no signs of recurrence. During the following 2 years the girl remained healthy with no respiratory symptoms.

Discussion

The causes of inspiratory stridor in infancy are numerous, the most common ones being infections in the upper respiratory tract and laryngomalacia. More rarely a nasal mass is the cause. Nasal midline masses in infancy include dermoids, gliomas, and encephaloceles. Other nasal masses include hemangiomas and tumours such as rhabdomyosarcoma, and as in the present case, the rare infantile HPC [3].

The first child with infantile HPC located in the rhinopharynx suffered from respiratory distress with inspiratory stridor, too [10]. Respiratory problems have also been described in a child with infantile HPC located elsewhere in the pharynx [1]. Even if location of infantile HPC in the rhinopharynx appears to be rare, this tumour should be suspected in an infant with inspiratory stridor and a mass in the pharynx.

HPC is a neoplasm originating from the pericytes, which are contractile cells surrounding vascular channels. Infantile HPC usually has a superficial location, the soft tissues of the head and neck and lower extremities being the most common locations [2, 4–5, 7–10]. From the histological point of view, HPC is difficult to separate, and a number of differential diagnoses have to be considered before diagnosing HPC merely by exclusion. Extrapleural, solitary fibrous tumour mostly shows universal, intense staining for CD34. The morphology and immunohistochemical profile are not consistent with synovial sarcoma or mesenchymal chondrosarcoma, and the clinical presentation and high proliferative rate seem to exclude the distinct entity of sinonasal HPC.

Moreover, a diagnosis of infantile HPC as a distinct entity is in itself debatable. There are a number of reasons to consider infantile HPC as part of a spectrum of infantile myofibroblastic lesions [5, 7–8], also including solitary myofibroma, myofibromatosis, and myopericytoma [6]. The morphology and immunohistochemical profile of the present rhinopharyngeal neoplasm seem best classified as belonging to the HPC like end of this spectrum of myofibromatous tumours.

Whenever possible, surgery is the preferable treatment [4–5, 8–9]. Spontaneous regression and regression after partial resection have been observed [2, 4–5, 7–9]. Because there are no definite histological criteria to predict which tumours will regress, complete or non-mutilating surgical excision is recommended in cases of small and localised tumours when non-mutilating surgery is possible [4–5, 9].

There is, however, excellent response to chemotherapy, and primary chemotherapy should be preferred to mutilating surgery [4–5, 8]. A primary course of chemotherapy is recommended in cases of unresectable tumours. A good clinical response and reduction in tumour size and cellularity making subsequent resection possible is well documented [4–5, 8–9]. Chemotherapy is also recommended in cases of aggressive, life threatening lesions and in cases of metastases or recurrence [5, 8–9]. An ideal chemotherapeutic regimen is unknown [4]. Chemotherapeutic regimens have included the use of vincristin, doxorubicin cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, adriamycin, and actinomycin-D [4–5, 8–9].

The role of radiotherapy has to be clarified [4–5, 9]. Cure by radiotherapy alone has been described [4].

In spite of histological features of high mitotic index, increased cellularity, necrosis, and haemorrhage, infantile HPC most often carries a favourable prognosis [2, 4–5, 7–10], but local recurrence and distant metastases occur [2, 4–5, 7–9]. Due to the rarity of the tumour the exact frequency of metastases or recurrence is not known. However, one review of 50 cases of infantile HPC (in 46 patients), reported from 1942 to 1992, showed three cases of recurrence and one case of metastases or possibly multiple primary tumours [2]. A case of pulmonary metastasis at the time of diagnosis has also been described [9]. In any case, a clinico-radiologic diagnostic screening for multicentricity is recommended at initial presentation.

Because of the unpredictable nature of the tumour, close and long-term follow-up is recommended [2, 4–5, 9]. For how long and at what intervals this follow up must be carried out is not clarified. It should, however, be emphasised that recurrence has occurred after 12 years [7].

References

Baden M, Papageorgiou A, Joshi VV, Stern L (1972) Upper airway obstruction in a newborn secondary to Hemangiopericytoma. Can Med Assoc J 107 (12):1202–1204

Baker DL, Oda D, Myall RW (1992) Intraoral infantile hemangiopericytoma: literature review and addition of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 73 (5):596–602

Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB (2004) Nelson textbook of pediatrics, 17th edn. Saunders, Philadelphia

Borg MF, Forstner DF, Benjamin CS (2003) Childhood hemangiopericytoma. Med Pediatr Oncol 40(5):331–334

Ferrari A, Casanova M, Bisogno G, Mattke A, Meazza C, Gronchi A, Cecchetto G, Fidani P, Kunz D, Treuner J, Carli M (2001) Hemangiopericytoma in pediatric ages: a report from the Italian and German soft tissue sarcoma cooperative group. Cancer 92(10):2692–2698

Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F (2002) WHO classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissues and bone. IARC-Press, Lyon, France

Mentzel T, Calonje E, Nascimento AG, Fletcher CDM (1994) Infantile hemangiopericytoma versus infantile myofibromatosis. Study of a series suggesting a continuous spectrum of infantile myofibroblastic lesions. Am J Surg Pathol 18:922–930

Rodriguez-Galindo C, Ramsey K, Jenkins JJ, Poquette CA, Kaste SC, Merchant TE, Rao BN, Pratt CB, Pappo AS (2000) Hemangiopericytoma in children and infants. Cancer 88(1):198–204

del Rosario ML, Saleh A (1997) Preoperative chemotherapy for congenital hemangiopericytoma and a review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 19(3):247–250

Seibert JJ, Seibert RW, Weisenburger DS, Allsbrook W (1978) Multiple congenital Hemangiopericytomas of the head and neck. Laryngoscope 88(6):1006–1012

Jonas K. Hansen, Mogens Fjord Christensen, and Flemming Brandt Soerensen are all responsible for the idea and planning of the article and have taken part in writing the manuscript. J.K. Hansen and M.F. Christensen have especially had emphasis on the clinical part and F.B. Soerensen on the histological part. All three authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hansen, J.K., Soerensen, F.B. & Christensen, M.F. A five-week-old girl with inspiratory stridor due to infantile hemangiopericytoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 263, 524–527 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-005-0003-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-005-0003-9