Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the study was to compare the effect of mefenamic acid and ginger on pain management in primary dysmenorrhea.

Methods

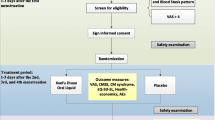

One hundred and twenty-two female students with moderate to severe primary dysmenorrhea were randomly allocated to the ginger and mefenamic groups in a randomized clinical trial. The mefenamic group received 250 mg capsules every 8 h, and the ginger group received 250 mg capsules (zintoma) every 6 h from the onset of menstruation until pain relief lasted 2 cycles. The intensity of pain was assessed by the visual analog scale. Data were analyzed by descriptive statistics, t test, Chi-square, Fisher exact test and repeated measurement.

Results

The pain intensity in the mefenamic and ginger group was 39.01 ± 17.77 and 43.49 ± 19.99, respectively, in the first month, and 33.75 ± 17.71 and 38.19 ± 20.47, respectively, in the second month (p > 0.05). The severity of dysmenorrhea, pain duration, cycle duration and bleeding volume was not significantly different between groups during the study. The menstrual days were more in the ginger group in the first (p = 0.01) and second cycle (p = 0.04). Repeated measurement showed a significant difference in pain intensity within the groups by time, but not between groups.

Conclusion

Ginger is as effective as mefenamic acid on pain relief in primary dysmenorrhea. Ginger does not have adverse effects and is an alternative treatment for primary dysmenorrhea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dysmenorrhea is the most common gynecological problem reported by women of reproductive age and a major cause of activity restriction [1–4]. Primary dysmenorrhea is defined as cramps in the suprapubic region during the menstrual phase without any pathology in the pelvis [4, 5]. It is believed that the cause of pain is excess production of prostaglandins in the endometrium during the ovulatory cycle, which results in uterine contraction and ischemia [3, 6]. Whenever organ pathology is the cause of pain, it is called secondary dysmenorrhea. In these patients, pain is mainly due to endometriosis and adenomyosis [7]. Deep infiltration of endometriosis is strongly associated with severe dysmenorrhea. It appears that the pain is due to the percentage of nerves located within endometriotic lesions and fibrotic nodules [8]. Dysmenorrhea results in absence from school or work and significant cost to the health care system [9, 10]. In addition, pain affects the quality of life in women [11]. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea in adolescents is reported to be 70–79 % [12].

Recent treatments for dysmenorrhea include prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors and herbal remedies [13]. According to some studies in women with dysmenorrhea, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are significantly effective for pain relief [5, 12, 14]. NSAIDs relieve primary dysmenorrhea through the inhibition of endometrial prostaglandin synthesis [5, 12, 14]. In contrast, adverse effects of NSAIDs include gastrointestinal and central nervous system symptoms, nephrotoxic and hepatotoxic effects, hematological abnormalities, bronco spasm and oedema [5, 12]. About 30 % of women with primary dysmenorrhea do not take these drugs due to the absence of therapeutic response or intolerance to gastrointestinal adverse events [15–17].

There is insufficient evidence to determine whether NSAIDs are the safest and the most effective treatment of dysmenorrhea [12]. Moreover, studies have indicated that the conventional treatment for primary dysmenorrhea has a failure rate of 20–25 % [18]. These treatments may be contradictory or not tolerated by some women with primary dysmenorrhea [19]. Thus, many women are seeking alternative medicines, of which herbal medicine is a common choice.

Ginger root is an old spice and has been used in traditional medicine for a long time and as an anti-inflammatory agent [20, 21]. Some studies have compared ginger with placebo and showed beneficial effects in primary dysmenorrhea [20, 22]. Only one study compared ginger with NSAIDs in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea, and reported it as effective as mefenamic acid [23].

However, there is insufficient evidence about the comparison of ginger and NSAIDs in primary dysmenorrhea, thus the effect of ginger and mefenamic acid on treatment of primary dysmenorrhea was assessed in this study.

Materials and methods

This randomized clinical trial was approved by the ethical committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki. Female students of this university who had primary dysmenorrhea were requested to report the most pain that was usually experienced during menstruation. One hundred and twenty-two students with moderate to severe dysmenorrhea participated in the study. The participants were randomly allocated to two interventional groups: the ginger and mefenamic groups. According to previous studies, the size effect of ginger 2.3 (SD = 2) and mefenamic acid 3.3 (SD = 1.2), α = 0/05 and β = 80 %, sample size was calculated 61 for each group [12, 23].

Students who were living in the residence, 18 and over years old, with primary dysmenorrhea at least in 50 % of menstrual cycles for 1 day and pain intensity over 40 mm based on a 100 mm visual analog scale (VAS), were included in the study [1, 2, 24]. Students who had irregular menstrual cycles, history of regular exercise, secondary dysmenorrhea and use of IUD or OCP were excluded [2]. As nutrition may influence dysmenorrhea, students were recruited from the dormitory because they had similar feeding [9]. MRI and laparoscopy were not performed for any of the participants.

After taking informed consent from participants, demographic information was recorded, including age, height, weight, menarche, menstrual days, regularity of menstrual cycle and amount of bleeding. Intensity of pain was measured with a 100 mm visual analog scale (VAS). Severity of pain was classified as: 40–60 mm as moderate, more than 60 mm as severe and less than 40 mm as mild.

Students in the mefenamic acid group received 250 mg capsules from the onset of the menstrual period, every 8 h until pain relief, for 2 cycles [23]. The ginger group received 250 mg capsules (zintoma) from the onset of menstruation, every 6 h until pain relief, for 2 cycles [23]. In the last day of menstruation, participants of both groups were asked to record the greatest intensity of pain that they experienced during menstruation. This was reported for the first and second menstruation. If participants needed to use more analgesics, they were asked to recorded pain intensity before taking extra drugs.

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequency), t test, Chi-square, Fisher exact test and repeated measurement were used for data analysis.

Results

Sixty-one students were assessed in each group. The mean age (21.62 ± 2.0 and 21.60 ± 2.14, respectively), BMI (21.84 ± 3.92 and 21.65 ± 3.08, respectively) and menarche (13.14 ± 1.15 and 13.29 ± 1.32, respectively) in the mefenamic and ginger groups were not different. The educational course of 45 (52.9 %) students in the mefenamic and 40 (47.1 %) in the ginger group was B.Sc. and the others educated in the upper courses, and the difference was not significant between the groups. Twenty-three (41.1 %) students in the mefenamic and 33 (58.9 %) in the ginger group were educated in the first and second years, and the others in upper years of university. This difference was significant between the groups (p = 0.05).

The pain intensity in the mefenamic and ginger group was 55.03 ± 14.95 and 58.01 ± 14.52, respectively, in the onset of the study. It was 39.01 ± 17.77 and 43.49 ± 19.99, respectively, in the first month and 33.75 ± 17.71 and 38.19 ± 20.47, respectively, in the second month. The intensity of pain was not significantly different between groups during the study. Furthermore, the severity of dysmenorrhea was not significantly different between the groups in the onset, and after the first and second months (Table 1). Repeated measurement showed a significant difference in pain intensity within the groups by time, but not between groups. Furthermore, there was not significant interaction between type of treatment and pain over time (Fig. 1).

Although the use of extra analgesic was higher in the ginger compared to the mefenamic group in the first month (31.1 and 18 %, respectively; p = 0.07), it was not significantly different. The same result was observed in the second month (16.4 and 14.8 % in the ginger and mefenamic group, respectively).

There were no significant differences between groups for characteristics of menstruation except for its duration in the first and second month, which was prolonged in the ginger group (Table 1). The changes in menstruation days were significant within groups (p = 0.001) and between groups (p = 0.03), but there were not significant interactions between groups and menstruation days over time.

Discussion

Ginger is traditionally used for various medical purposes such as management of pain [21]. In traditional medicine, ginger has been introduced as an effective substance for treatment of dysmenorrhea [25, 26]. These research-based results also demonstrate that ginger resulted in reduced pain intensity in the first and second months following taking ginger in this respect; it was not different from mefenamic acid. In a clinical trial, by prescribing 250 mg ginger, four times daily for 3 days, Ozgoli et al. [23] compared the effect with ibuprofen and mefenamic acid. Authors reported that ginger works effectively like the two mentioned drugs in reducing dysmenorrhea. Moreover, prescribing 500 mg ginger capsules, 3 times daily, Rahnama et al. [20] reported initial dysmenorrhea intensity reduction. Comparing ginger with zinc sulfate, Kashefi et al. [27] reported that both showed the same effect on the young women recovering from initial dysmenorrhea. In the study by Jenabi [22], pain significantly decreased in those receiving 500 mg ginger, 3 times daily for 3 days, compared to placebo. Comparing the effect of 1 g ginger powder, twice a day for 3 days, Halder [28] declared ginger was more effective than progressive muscular relaxation in decreased pain in dysmenorrhea. The study by Chen et al. [29] also indicated that ginger induced relief of dysmenorrhea. In the present study compared to the above studies, although the lower dose of ginger was used, pain relief was observed. Some adverse side effects such as stomach epithelial cell desquamation, sensitivity reactions, dermatitis, depression of nervous system and cardiac arrhythmia have been reported by high doses of ginger [23]. Thus, it appears probable that adverse side effects can be reduced with lowering the ginger dose, with no decrease in its effect.

Ginger relieves dysmenorrhea via various ways. The effect of ginger on dysmenorrhea is dependent on the inhibition of thromboxane and prostaglandins activity [30]. One of the mechanisms behind creating dysmenorrhea is prostaglandins production in endometrium, which stimulates myometrium contractions [31]. Prostaglandins are produced by cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase from arachidonic acid [32, 33]. In the menstruation blood of women suffering from dysmenorrhea, the concentrations of prostaglandin F2ά and E2 are higher [34]. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as mefenamic acid inhibit prostaglandins synthesis through inhibition of cyclooxygenase activity [12]. Ginger compounds like any other plant are very complex and include various substances such as Gingerol, Gingerdio, Gingerdione, Beta carotene, Capsaicin, Caffeinic acid and Curcumin [35, 36]. It appears that ginger’s effect on dysmenorrhea is applied through its compounds Gingerol and Gingerdiones. By controlling cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase activity [37, 38], these compounds inhibit leukotriene and induce anti-inflammatory effects [20, 33], and as a result, suppress prostaglandin production [20, 23, 39]. Thus, it appears ginger leads to decreasing dysmenorrhea intensity similar to mefenamic acid with anti-prostaglandin effects. Another mechanism is ginger's effect on thromboxane synthesis inhibition, which results in activating endorphin receptors and inhibiting noradrenergic overactivity [30]. It is possible that using ginger is closely associated with decreased endothelin 1 and increased no [40]. Nitrous oxide improves pelvic circulation by expanding vessels, and may prevent prostaglandin aggregation. As another probable mechanism, the pungent components of ginger strongly and specifically inhibit interleukin-1beta in macrophages [41]. Furthermore, researchers point out that salicylate in fresh ginger root has relieving and anti-inflammatory effects, and can be used for treating smooth muscles disorders [25]. So it may be effective on pain relief in dysmenorrhea.

In the current research, the menstruation days in ginger users were more than those taking mefenamic acid, and the change in bleeding volume, menstrual and pain days showed no significant difference between the two groups. In a study by Rahnama et al. [20], pain duration was significantly lower through prescribing ginger 2 days before menstruation until 3 days after onset, than the time, when ginger was taken as menstruation started. Therefore, it is possible that the early start of taking ginger lowers pain duration and since in this study, ginger consumption started with menstruation, this effect has not been observed.

Although in a study by Rahnama, some participants reported heartburn as the side effect of the drug; no adverse side effect such as digestive problems was reported in the ginger users’ group in the present study. It may be due to higher doses of ginger that applied in a study by Rahnama. German Commission E Monographs also has reported no side effect or interference with other drugs used with ginger [42]. Ginger has therefore been introduced as a safe herbal medicine [37].

The limitations of the present research were lack of studying the various doses of ginger, the starting time effect on dysmenorrhea, not measuring bleeding volume, small sample size and involvement of only one site for recruitment. Comparing the effect of ginger with other NSAIDs, and to assess the effect of ginger in association with other herbal compounds on primary dysmenorrhea, is suggested for future studies.

References

Abbaspour Z, Rostami M, Najjar S (2006) The effect of exercise on primary dysmenorrhea. J Res Health Sci 6(1):26–31

Brown J, Brown S (2010) Exercise for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004142

Cakir M, Mungan I, Karakas T, Girisken I, Okten A (2007) Menstrual pattern and common menstrual disorders among university students in Turkey. Pediatr Int 49(6):938–942

Lefebvre G, Pinsonneault O, Antao V, Black A, Burnett M, Feldman K et al (2005) Primary dysmenorrhea consensus guideline. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 27(12):1117–1146

Dawood MY (2006) Primary dysmenorrhea: advances in pathogenesis and management. Obstet Gynecol 108(2):428–441

French L (2005) Dysmenorrhea. Am Fam physician 71(2):285–291

Pistofidis G, Koukoura DG, Bardis NS, Filippidis M (2010) Laparoscopic treatment of a case of cystic adenomyosis of the lower uterine wall. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 17(6):S97

Anaf V, Simon P, Nakadi EI, Fayt I, Buxant F, Simonart T et al (2000) Relationship between endometriotic foci and nerves in rectovaginal endometriotic nodules. Hum Reprod 15(8):1744–1750

Abdul-Razzak KK, Ayoub NM, Abu-Taleb AA, Obeidat BA (2010) Influence of dietary intake of dairy products on dysmenorrhea. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 36(2):377–383

Reddish S (2006) Dysmenorrhoea. Aust Fam Physician 35(11):842–844, 846–849

Cheng HF, Lin YH (2011) Selection and efficacy of self-management strategies for dysmenorrhea in young Taiwanese women. J Clin Nurs 20(7–8):1018–1025

Marjoribanks J, Proctor ML, Farquhar C, Derks RS (2010) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 20(1):CD001751. doi: 10.1002/14651858

Bolton PJ, Del Mar C, O’Connor V, Dean LM, Jarrett MS (2012) Exercise for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Libr. doi:10.1002/14651858

Proctor M, Farquhar C (2006) Diagnosis and management of dysmenorrhea. BMJ 332(7550):1134–1138

Campbell MA, McGrath PG (1997) Use of medication by adolescents for the management of menstrual discomfort. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 151(9):905–913

Higuchi K, Umegaki E, Watanabe T, Yoda Y, Morita E, Murano M et al (2009) Present status and strategy of NSAIDs-induced small bowel injury. J Gastroenterol 44(9):879–888

Traversa G, Walker AM, Ippolito FM, Caffari B, Capurso L, Dezi A et al (1995) Gastroduodenal toxicity of different nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Epidemiology 6(1):49–54

Zhu, X, Proctor M, Bensoussan A, Wu E, Smith CA (2008) Chinese herbal medicine for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 16(2):CD005288. doi:10.1002/14651858

Proctor M, Murphy PA (2001) Herbal and dietary therapies for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD002124. doi: 10.1002/14651858

Rahnama P, Montazeri A, Huseini HF, Kianbakht S, Naseri M (2012) Effect of Zingiber officinale R. rhizomes (ginger) on pain relief in primary dysmenorrhea: a placebo randomized trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 12(1):92. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-12-92

Terry R, Posadzki P, Watson LK, Ernst E (2011) The use of ginger (Zingiber officinale) for the treatment of pain: a systematic review of clinical trials. Pain Med 12(12):1808–1818

Jenabi E (2013) The effect of ginger for relieving of primary dysmenorrhoea. J Pak Med Assoc 63(1):8–10

Ozgoli G, Goli M, Moattar F (2009) Comparison of effects of ginger, mefenamic acid, and ibuprofen on pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med 15(2):129–132

Shahr-jerdy S, Hosseini RS, Gh ME (2012) Effects of stretching exercises on primary dysmenorrhea in adolescent girls. Biomed Human Kinet 4:127–132

Altman R, Marcussen K (2001) Effects of a ginger extract on knee pain in patients with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 44(11):2531–2538

Mills S, Bone K (2000) Principles and practice of phytotherapy: modern herbal medicine. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh

Kashefi F, Khajehei M, Cher MT, Alavian M, Asili J (2014) Comparison of the effect of ginger and zinc sulfate on primary dysmenorrhea: a placebo-controlled randomized trial. Pain Manag Nurs. doi:10.1016/j.pmn.2013.09.001

Halder A (2011) Effect of progressive muscle relaxation versus intake of ginger powder on dysmenorrhoea amongst the nursing students in Pune. Nurs J India 103(4):152–156

Chen CK, Huang YP, Fang HL, Huang YY (2013) Dysmenorrhea: a study of affected factors and approaches to relief among female students at a college in southern Taiwan. Hu li Za Zhi 60(3):40–50

Backon J (1991) Mechanism of analgesic effect of clonidine in the treatment of dysmenorrhea. Med Hypotheses 36(3):223–224

Kim JK, Kim Y, Na KM, Surh YJ, Kim TY (2007) Gingerol prevents UVB-induced ROS production and COX-2 expression in vitro and in vivo. Free Radic Res 41(5):603–614

Bieglmayer C, Hofer G, Kainz C, Reinthaller A, Kopp B, Janisch H (1995) Concentrations of various arachidonic acid metabolites in menstrual fluid are associated with menstrual pain and are influenced by hormonal contraceptives. Gynecol Endocrinol 9(4):307–312

Grzanna R, Lindmark L, Frondoza CG (2005) Ginger-an herbal medicinal product with broad anti-inflammatory actions. J Med Food 8(2):125–132

Ife J, Magowan B (2004) Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. WB Saunders, Edinburgh

Kikuzaki H, Nakatani N (1996) Cyclic diarylheptanoids from rhizomes of Zingiber officinale. Phytochemistry 43(1):273–277

Schulick P (1996) Ginger: common spice and wonder drug. Herb Free Press, Brattleboro

Ali BH, Blunden G, Tanira MO, Nemmar A (2008) Some phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe): a review of recent research. Food Chem Toxicol 46(2):409–420

Kim SO, Kundu JK, Shin YK, Park JH, Cho MH, Kim TY et al (2005) Gingerol inhibits COX-2 expression by blocking the activation of p38 MAP kinase and NF-κB in phorbol ester-stimulated mouse skin. Oncogene 24(15):2558–2567

Kiuchi F, Iwakami S, Shibuya M, Hanaoka F, Sandawa U (1992) Inhibition of prostaglandin and leukotriene biosynthesis by gingerols and diarylheptanoids. Chem Pharm Bull 40:187–191

Yang JJ, Sun LH, She YF, Ge JJ, Li XH, Zhang RJ (2008) Influence of ginger-partitioned moxibustion on serum no and plasma endothelin-1 contents in patients with primary dysmenorrhea of cold-damp stagnation type. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu 33(6):409–412

Nievergelt A, Marazzi J, Schoop R, Altman KH, Gertsch J (2011) Ginger phenylpropanoids inhibit IL-1β and prostanoid secretion and disrupt arachidonate-phospholipid remodeling by targeting phospholipases A2. J Immunol 187(8):4140–4150

Blumenthal M, Busse WR, Goldberg A (1998) The complete german commission e monographs: therapeutic guide to herbal medicines. Integrative Medicine, Boston

Acknowledgments

We thank the vice-chancellor for research of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences for support this study. Our special thanks to students who participated in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical standard

This research has been approved by Ethics Committee of this deputy, conformity with Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

All persons gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shirvani, M.A., Motahari-Tabari, N. & Alipour, A. The effect of mefenamic acid and ginger on pain relief in primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet 291, 1277–1281 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-014-3548-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-014-3548-2