Abstract

Purpose

To compare laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LSH) with total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) with regard to relevant surgical parameters and risk factors of conversion to laparotomy and complications.

Methods

This prospective, open, single-center, interventional study included women with benign gynecologic disease who underwent standardized LSH or TLH. The techniques were compared for conversion rate and mean operating time, hemoglobin drop, hospital stay, and complication rates using descriptive statistics and standard non-parametric statistical tests. Risk factors of conversion and complications were identified by logistic regression analysis.

Results

During January 2003 to December 2010, 1,952 women [mean age (SD): 47.5 (7.2) years] underwent LSH [1,658 (84.9 %)] or TLH [294 (15.1 %)], mostly (>70 %) for uterine fibroids. Significant differences in surgical parameters were observed for conversion rate (LSH/TLH: 2.6/6.5 %), mean operating time [87 (34)/103 (36) min], hemoglobin drop [1.3 (0.8)/1.6 (1.0) g/dL], and hospital stay [4.3 (1.5)/4.9 (2.8) days]. Overall intraoperative (0.2/0.7 %) and long-term (>6 weeks) post-operative (0.8/1.7 %) complication rates did not differ significantly, but the short-term LSH complication rate was significantly lower (0.6 vs. 4.8 %). Spotting (LSH, 0.2 %) and vaginal cuff dehiscence (TLH, 0.7 %) were long-term method-specific complications. Logistic regression showed that uterine weight and extensive adhesiolysis were significant factors for conversion while previous surgery, age, and BMI were not. Major risk factors of short-term complications were age, procedure (LSH/TLH), and extensive adhesions.

Conclusions

Both procedures proved effective and were well tolerated. LSH performed better than TLH regarding most outcome measures. LSH is associated with very low rates of re-operation and spotting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Supracervical, or subtotal, hysterectomy has regained popularity with the advent of laparoscopy [1]. The reasons for performing laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LSH) where vaginal hysterectomy is not possible include faster recovery from surgery than with total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) as well as a lower risk of post-operative vaginal prolapse as the vaginal structures remain intact [2]. There are also several indicators showing that, compared with total hysterectomy, a patient’s sexuality is less affected if the cervix remains in place. However, the data published so far are sparse and often contradictory, and therefore, it remains unclear whether LSH or TLH should generally be preferred [3].

In regard to the potential advantages of retaining the cervix, a prospective trial of total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) versus supracervical abdominal hysterectomy (SAH) showed no significant differences in coital frequency or libido 1 year after surgery but found that dyspareunia was significantly less in the SAH group while TAH was associated with a significant reduction in orgasmic coituses [4]. A more recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) of TAH versus SAH in 279 women observed no changes in sexual function after surgery or differences between groups with regard to sexual function after TAH versus SAH [5].

Since the publication of these earlier studies there have been considerable technical advances, e.g., improvements in laparoscopic uterine morcellation and thermal coagulation, which warrant reassessment of the pros and cons of LSH versus TLH.

With the exception of one relevant report [6], most studies published so far have neglected the rate of technique-related specific repeat surgery such as cervical stump excision (CSE) after LSH, which may become necessary due to the preservation of the cervix, or vaginal cuff dehiscence (VCD) revision after TLH [7].

The purpose of this prospective, single-center, interventional study was to investigate and compare the intraoperative and post-operative outcomes in patients undergoing LSH or TLH in accordance with our institution’s guidelines. Our objective was to compare the two techniques and identify potential differences in the rates of conversion to laparotomy, intraoperative complication rates, short- and long-term post-operative complication rates, operating time, hemoglobin drop, and length of hospital stay. These measurements were obtained while implementing LSH and TLH at our institution.

Methods

Patients

Patients eligible for inclusion in the study were women aged over 18 years who underwent LSH or TLH for benign uterine disease consecutively at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the University of Tübingen, Germany, during the 8-year period from January 2003 to December 2010. Exclusion criteria included malignancy, planned laparotomy, deep infiltrating endometriosis, and urogenital prolapse. Intraoperative conversion from laparoscopy to laparotomy, which became necessary mostly for anatomical reasons such as bulky uterus or massive intraoperative adhesions, was not considered an exclusion criterion.

Study design

This was a prospective, open, single-center, comparative interventional study of two minimally invasive surgical techniques. The pre-operative workup included vaginal ultrasound, clinical examination, and detailed consultation with a member of the surgical team. The choice of surgical procedure, LSH or TLH, was determined in accordance with our institution’s indication-based guidelines. Thus, women with cervical pathology such as an abnormal Pap smear or a history of human papilloma virus (HPV) infection were advised to undergo TLH. Patients with a healthy cervix were advised to undergo LSH but were informed about TLH and offered this alternative if they preferred not to retain the healthy cervix. All patients undergoing TLH were strongly advised to refrain from sexual intercourse for at least 6–8 weeks after surgery.

The study protocol received prior approval from the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Tübingen.

Patient demographic, clinical, and surgical data were prospectively collected and extracted from the hospital records and operative reports for statistical analysis.

Demographic data included age at surgery, body mass index (BMI), and a previously described surgery score [7], calculated as 1 point per laparoscopy plus 2 points per laparotomy (including cesarean sections).

Surgical parameters assessed included uterine weight; conversion to laparotomy; intraoperative complications and short-term (≤6 weeks after surgery) and long-term (>6 weeks) post-operative complications; drop in hemoglobin concentration after surgery; operating time; adhesiolysis; and length of hospital stay.

Intraoperative complications were defined as occurring during surgery and included hemorrhage requiring transfusion, uterine bleeding requiring transfusion, and iatrogenic injury to the bowel, ureter bladder, or epigastric artery. Short-term post-operative complications were defined as complications occurring up to 6 weeks after surgery and requiring surgical intervention, and included pelvic peritonitis, hematoma (vaginal vault, cervical stump, and other hematoma) requiring surgical intervention, bowel injury, re-operation due to adhesions, post-operative bleeding, and other complications (not specified). Long-term complications comprised post-operative events occurring >6 weeks after surgery and requiring surgical intervention, including pelvic peritonitis, spotting, cervical descensus, necessity of cervical stump excision (CSE; the latter three after LSH only), vaginal cuff dehiscence (VCD; after TLH only), and re-operation due to adhesions. Of particular interest were technique-specific re-operations, especially CSE after LSH and VCD revision after TLH.

The drop in hemoglobin concentration was calculated as the difference between the pre-operative concentration and the concentration on the first day after surgery. Operating time was measured from insertion of the Veress needle to skin closure. The length of hospital stay was calculated in days, including the day of admission and the day of discharge.

Main outcome measures were conversion rate, intraoperative (Veress needle insertion to skin closure) and short-term and long-term post-operative complications, operating time, hemoglobin drop, and length of hospital stay.

Surgical techniques

Both techniques were essentially performed as previously described [8] in the context of implementing standardized methods at our institution. This also involved the introduction of innovative instruments, such as a new morcellator [9] and a monopolar loop, the SupraLoop™ [10], which were further adapted to the specific requirements.

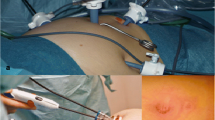

In brief, for LSH or TLH, the patient was placed in a supine position under general anesthesia. The abdomen and vagina were disinfected and a bladder catheter was inserted via the urethra. The patient was draped and placed in a Trendelenburg position before insertion of the Veress needle, insufflation of the abdomen with carbon dioxide and placement of the trocars.

LSH

The Tintara uterus manipulator (Karl Storz GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany) was introduced into the uterine cervix. First, the round ligaments and then the tubes and the proper ovarian ligaments were dissected using a bipolar forceps (RoBi®, Karl Storz GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany). Anterior and posterior layers of the parametrium were dissected, followed by thorough coagulation and dissection of the uterine artery. Using the tension of the Tintara manipulator, the vesical peritoneum was dissected, resulting in dislocation of the vaginal fornices from the bladder as well as lateralization of the bladder pillars. The anterior fornix of the vagina was dissected using the SupraLoop™ [10] and morcellated intra-abdominally with the Rotocut™ (both from Karl Storz GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany) [9]. Finally, the cervix was desiccated to prevent spotting.

TLH

The Hohl manipulator (Karl Storz GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany) was introduced into the uterine cervix. The subsequent surgical steps were performed in the same manner as for LSH, except that the anterior fornix of the vagina was dissected using a monopolar needle (Karl Storz GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany). The uterus was then removed vaginally using the Hohl manipulator. Suturing was performed using Monocryl CT2 sutures (Ethicon EndoSurgery Inc., Cincinnati OH, USA).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed as mean and standard deviation (SD), median and range, numbers and percentages, as appropriate. Differences between the LSH and the TLH group were tested using the Wilcoxon rank sum test and Fisher’s exact test. A significance level of 0.05 was chosen.

In order to identify important risk factors in laparoscopic hysterectomy for conversion to laparotomy, multiple logistic regression models were formulated. Major factors were identified by forward and backward stepwise selection (F-to-enter = 0.1, F-to-leave = 0.1) of the following factors: surgical procedure (LSH/TLH), age at surgery, BMI, previous surgeries, uterine weight, and minimal or extensive adhesiolysis. Goodness of fit was assessed by McFadden Pseudo R 2.

All statistical tests and modeling were performed with the software R, version 2.12.1 (http://www.r-project.org/).

We used a custom questionnaire to analyze specific long-term repeat operations such as CSE in the LSH group and VCD revision in the TLH group. The answers from each participant were then reviewed for inconsistencies. Data were considered inconsistent if participants entered incoherent information or if answers to questions repeated elsewhere in the questionnaire were contradictory. The questionnaire data were checked against patients’ hospital records.

Results

In total, 2,291 consecutive patients underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the University of Tübingen during the study period from 1 January, 2003 through 31 December, 2010 and were assessed for inclusion in the present analysis. Of these patients, 339 were excluded due to malignant tumor (283 patients), planned laparotomy (27), radical hysterectomy (1) or other reasons (28 patients, including 15 who had borderline malignancies). There were no patients with deep infiltrating endometriosis. The remaining 1,952 patients (mean age ± SD: 47.5 ± 7.2) were included in the analyses. LSH and TLH were performed in 1,658/1,952 (84.9 %) and 294/1,952 (15.1 %) patients, respectively.

For the questionnaire study, 62 of the 1,952 patients were excluded due to conversion to laparotomy and four for other reasons. A total of 1,886 questionnaires were sent out to patients between 2009 and 2012. After screening the 918 returns for inconsistencies, 915 completed questionnaires were included in the analysis [return rate of questionnaires sent out was 48.5 % (46.9 % of all patients)]. Mean follow-up time was 2.5 years, the minimum follow-up being 8 months. No cases of cervical cancer were reported in the study population during follow-up.

With regard to indications for surgery, the most frequent overall indications for surgery were menstrual disorders and uterine fibroids, which accounted for approximately 75 and 72 % of indications, respectively (a patient may have had one or several indications). Less frequent indications included adenomyosis (4 %).

Sample size calculations showed that a Wilcoxon rank test with n 1 = 1,658 (LSH group), n 2 = 294 (TLH group), and the usual 5 % significance level would detect an effect size of 0.18 with the usual power of 80 %, meaning it would detect a difference as small as one-fifth of a given SD. Thus, the large overall sample size enabled detection of both large differences and small effects despite the unequal sample sizes.

In total, 1,868/1,952 (95.7 %) operations were carried out by 14 surgeons, of whom four each performed >200 surgeries, three did >150 and three did >100 surgeries, together accounting for 1,763 (90 %) of all hysterectomies. The remaining four surgeons performed up to 30 hysterectomies as first surgeon and were always assisted by one of the four most experienced surgeons.

Table 1 summarizes the baseline and surgical characteristics of the 1,952 LSH and TLH patients analyzed.

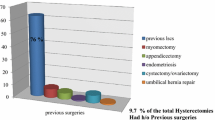

No statistically significant differences were found between the LSH and the TLH group with regard to age at surgery, BMI, and adhesiolysis. However, the groups differed significantly with respect to previous surgery score, with LSH patients having had fewer previous operations.

The two groups did not differ significantly in respect of uterine weight (p = 0.508). The rate of conversion to laparotomy was significantly lower in LSH patients than in TLH patients. Reasons for conversion occurring more than once included large fibroid uterus [21 (1.3 %) LSH and 9 (3.1 %) TLH patients], extensive adhesions [10 (0.6 %) LSH and 5 (1.7 %) TLH patients], and the combination of both [3 (0.2 %) LSH patients]. Mean operating times (±SD) for typical LSH and TLH procedures were 87 ± 34 min and 103 ± 36 min, respectively, with LSH taking significantly less time to complete (p < 0.001). Hemoglobin drop was significantly lower in LSH patients (p < 0.001). Furthermore, mean hospital stay was significantly shorter (p = 0.001).

Table 2 presents a detailed analysis of intraoperative and post-operative complications associated with LSH and TLH in the 1,952 patients analyzed. Intraoperative complications and short- and long-term post-operative complications never occurred in the same patient.

With LSH, intraoperative complications occurred in four patients (uterine bleeding requiring blood transfusion, ureteric injury, injury to the bladder, and bleeding from the epigastric artery, each occurred once in different patients).

With TLH, the only intraoperative complication was a major hemorrhage requiring surgical intervention (major hemorrhage requiring surgical intervention with blood transfusion occurred in one patient with an extremely large fibroid uterus, and accidental injury to the inferior vena cava requiring surgical repair and blood transfusion occurred in another patient).

Short-term post-operative complications after LSH and TLH primarily consisted in pelvic peritonitis and various types of hematoma requiring intervention. The overall rate of short-term post-operative complications after LSH was significantly (p < 0.001) lower than after TLH.

Long-term post-operative complications requiring surgical intervention primarily consisted in spotting after LSH (not requiring surgery; three patients) and VCD after TLH (two patients) in addition to adhesions. No LSH patient had cervical descensus or required CSE. The overall rate of long-term post-operative complications after LSH was not significantly (p = 0.173) lower than after TLH.

In total, seven long-term complications only became known when they were reported via the questionnaire sent out to patients 6 months or more after surgery. Based on the yield questionnaire rate of 46.9 %, an estimated approximately eight additional complications would have been reported if all patients had responded, thus increasing the overall complication rate from the observed 2.4 % to an estimated 2.8 % (to 1.6 % for LSH and 7.9 % for TLH).

Logistic regression analyses performed to identify predictive factors of intraoperative conversion to laparotomy and intraoperative and post-operative complications yielded the following results. Table 3 shows the final logistic regression model obtained for rate of conversion to laparotomy. Factors were selected from surgical procedure (LSH or TLH), age at surgery, BMI, previous surgeries, uterine weight, and extent of adhesiolysis.

For conversions, backward and forward stepwise selection led to the same regression models (F-to-enter = 0.1; F-to-leave = 0.1). This was also the case for short-term post-operative complications. The respective McFadden Pseudo R 2 values were 0.23 and 0.20, i.e., within acceptable ranges.

For prediction of conversions to laparotomy (Table 3), the final model included age at surgery, surgical procedure, uterine weight, and adhesiolysis, with the latter three being significant factors. Here, BMI and previous surgeries appear to lack importance for the prediction of post-operative complications.

The likelihood of conversion to laparotomy increased with uterine weight. A 100-g increase in uterine weight was associated with an OR of 1.59, i.e., with a 60 % increase in odds of conversion. The statistically significant OR of 0.386 for LSH versus TLH clearly indicates that in our study LSH patients were considerably less likely to undergo conversion than were the TLH patients. Patients who required extensive adhesiolysis had a significantly increased OR of 2.22 for conversion relative to patients without adhesiolysis. For patients with minor adhesiolysis, the observed OR was 0.42, i.e., the odds of conversion was decreased by more than one-half by minor adhesiolysis—the opposite of what one might expect.

Age at surgery was included in the final model, but was not a statistically significant factor.

Intraoperative complications did not yield a reliable logistic regression model for predictive factors due to the very small number of 4 patients with such complications in our study.

For prediction of short-term post-operative complications (Table 4; n = 24), two of four factors included in the final model—age at surgery and surgical procedure—were statistically significant. BMI and previous surgeries were discarded or not chosen by the stepwise selections and therefore, appear to lack importance for the prediction of post-operative complications, while uterine weight just failed to attain statistical significance. For adhesiolysis, the comparison of extensive versus none yielded a significant difference whereas minor versus none did not.

The odds ratio (OR) for a short-term post-operative complication after LSH versus TLH was only about 10 %. Patients with minor adhesiolysis had a statistically nonsignificant OR of approximately 1.7 relative to patients without adhesiolysis. In contrast, extensive adhesiolysis versus no adhesiolysis was associated with a significantly increased OR of 3.5. The OR for age at surgery was significantly smaller than 1, indicating that a patient of a given age carried a lower risk of short-term post-operative complications than a younger patient, the opposite of what one would expect. By comparison, a 10-year-old patient had an OR of 0.41, i.e., she carried less than half the odds of experiencing short-term post-operative complications.

Predictive factors of long-term post-operative complications were not reliably identifiable by logistic regression analysis in our study due to the relatively small number of 18 patients with such complications. Nevertheless, the analysis suggested that BMI might be a predictor of long-term post-operative complications (data not shown).

Finally, logistic regression analysis of the LSH data alone yielded results (data not shown) that were very similar to those for the combined LSH and TLH data.

Discussion

This was the first prospective single-center interventional study to be conducted at a major university hospital in Germany with the aim of comparing LSH and TLH in patients undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign uterine disease.

Our objective was to compare the two complex laparoscopic procedures as described elsewhere in detail [8] in a university, multi-surgeon setting with regard to the rate of conversion from laparoscopy to laparotomy, intraoperative and short- and long-term post-operative complications, operating time, post-operative hemoglobin drop, and length of hospital stay after introducing innovative instruments and equipment [9, 10] and standardized surgical techniques [8] to implement quality assurance and provide appropriate advanced surgical training at our academic center. In addition, we used logistic regression analysis to identify potential predictive factors of conversion and complications.

Study cohort characteristics

Included in the analysis were 1,952 out of 2,291 consecutive patients who underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy at our institution during 2003–2010. LSH and TLH were performed in 1,658/1,952 (84.9 %) and 294/1952 (15.1 %) patients, respectively. No cervical carcinoma was seen in the study population during follow-up.

There were no statistically significant differences between LSH and TLH patients with regard to age at surgery, BMI, uterine weight, and adhesiolysis. However, LSH patients had a slightly, but statistically significantly lower mean previous surgery score, i.e., fewer laparoscopies, laparotomies, and cesarean sections.

Mean uterine weight in our study population was 206 ± 184 g for LSH patients and 220 ± 205 g for TLH patients as compared with respective values of 316.4 ± 245.1 and 242.7 ± 197.8 g for LSH and TLH as reported by Boosz et al. [7] and 212.5 ± 177.0 g for LSH as reported by Bojahr et al. [11]. Notably, the latter study reported data generated by a single surgeon. Hence, in our opinion, these results are not directly comparable with ours, which reflect the experience of a high-volume center with many surgeons and a training and mentorship program.

Conversion rate, operating time, hemoglobin drop, and hospital stay

Compared with TLH, LSH was associated with significantly less frequent conversion to laparotomy (2.6 vs. 6.5 %); shorter mean (±SD) operating time (87 ± 34 vs. 103 ± 36 min) for hysterectomies without additional procedures such as unplanned laparotomy, myomectomy or other additional procedures; decreased mean hemoglobin drop (1.3 ± 0.8 vs. 1.6 ± 1.0 g/dL); and shorter mean hospital stay (4.3 ± 1.5 vs. 4.9 ± 2.8 days). The differences in hemoglobin drop and hospital stay, though statistically significant, were not of clinical significance. They are nevertheless reported for scientific completeness.

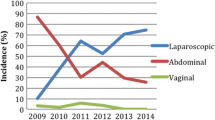

Conversion rates in our study thus were somewhat higher than in other studies [0.82 % (LSH only) [12], 0 (LSH) and 0.2 % (TLH) [7] and 0.88 % (LSH only) [13]]. This is possibly explained by the fact that most conversions occurred during the first 2 years. Conversions in the TLH group during this period were mainly due to larger uteri or intraoperative complications.

Mean operating times for typical LSH and TLH procedures in our study were comparable with those from other university and teaching hospital studies (103 ± 41 and 104 ± 44 min [7], 141 ± 60 and 181 ± 67 min [14], 77 ± 33 min (LSH only [13]) and from a three-surgeon experience of LSH at a private hospital (91 ± 33 min [12]).

In the context of implementation and learning processes, the following very recent studies are of relevance. A recent study concluded that surgical volume is one of the most important surgeon and system characteristics, with a 25 % risk reduction for patients operated on by high-volume surgeons [15]. The learning curve of the surgeons is of fundamental importance to the standardization process at the center level as evidenced by a recent report [16]. Others found that experience of 30 or more procedures was associated with a decrease in operating time [17]. A very recent study showed that significant improvement in surgical outcome of laparoscopic hysterectomy in terms of blood loss <200 mL tends to continue up to 125 procedures [18].

Length of hospital stay in our study (whole days, including the admission and discharge days) was considerably longer than the US average for laparoscopic hysterectomies [19–21]. This is attributable to the tradition in Germany and other European countries to provide maximum care and safety by keeping abdominal surgery patients hospitalized until complete recovery, although same-day discharge after laparoscopic hysterectomy has very recently been reported from Denmark [22]. However, the traditional attitude is gradually changing in Germany under the pressure of cost-effectiveness considerations and reimbursement by diagnosis-related group (DRG). Nonetheless, even the latest DRG reimbursement catalog is based on an average hospital stay of 5.4–7.6 days for hysterectomies [23]. From this perspective, hospital stay as in our study [4.3 (1.5) and 4.9 (2.8) days for LSH and TLH] is shorter today than it was even a decade or two ago.

Complications

Intraoperative complication rates in our study were 0.2 % for LSH and 0.7 % for TLH and thus lower than in other recent studies, which reported respective rates of 1.0 and 1.2 % [7] and 1.35 and 1.59 % [6]. Another study reported an intraoperative complication rate of 1.42 % for LSH [24]. The variability in these findings may be attributable to differences in instrumentation and surgical technique, but also in the clinical characteristics of the patient populations, e.g., uterine weight or number of previous surgeries.

Total post-operative complication rates in our study were 1.4 % for LSH and 6.4 % for TLH. Other studies have reported respective LSH and TLH complication rates of 0.3 and 1.9 % [6] and of 0.3 and 1.9 % [7]. These studies thus also found a higher complication rate in the TLH group. LSH-only studies reported post-operative complication rates of 1.2 % for a three-surgeon center [12] and 1.07 % for a teaching hospital of standard care [13]. In a large retrospective single-center study of laparoscopic hysterectomies, the overall complication rate in 1,613 LSH patients was 1.36 % [25].

A possible explanation for the slightly higher complication rate observed in our study is the fact that patients in the TLH group had a significantly higher previous surgery score (2.2 vs. 1.9 for LSH). The difference may, however, also be attributable to other factors such as surgical volume or subpopulation sizes.

The low spotting rate of 0.18 % we observed after LSH is possibly explained in that our technique leaves only a minimal portion of the cervix in place and ensures that the remaining functional endometrium is extensively coagulated.

The main reason for TLH-related complications associated with hemorrhage in our study was post-operative bleeding from the uterine artery and vaginal blood vessels, most likely resulting from laparoscopic closure of the vagina. As a preventive measure, closure of the vagina was switched to the vaginal route in the course of time after the first 2 years. This decreased hemorrhage-related complications. Moreover, to minimize the risk of VCD, patients were strongly advised to refrain from sexual intercourse for at least 8 weeks after surgery.

Comparison of complication rates across studies is difficult due to the different definitions used. Whereas several studies limited their scope to intraoperative complications [11], some distinguishing between major and minor perioperative complications [14, 25], others differentiated between intraoperative and post-operative complications [12]. We analyzed complications requiring surgical intervention, i.e., complications other authors would have classified as major. The distinction between intraoperative and short-term and long-term post-operative complications was chosen because we were interested in comparing LSH and TLH with regard to not only the immediately surgical aspects but also their intermediate and long-term clinical outcomes and success rates.

In recent years, there have been efforts to optimize TLH and reduce complication rates through more intensive and regular training [26, 27].

Re-operations

To further optimize both surgical procedures, we asked patients via questionnaire (return rate 48.5 %) to report specific long-term complications such as secondary CSE due to continuing spotting or bleeding and cervical dehiscence in the LSH group and VCD in the TLH group. In addition, data on long-term complications were extracted from patient records and also included in the analysis.

Whereas none of the LSH patients in our study reported cervical descensus or had to undergo CSE, 2 (0.7 %) TLH patients had to undergo repair surgery for VCD. By comparison, dehiscence rates have recently been reported as 0.28–1.2 %, independently of vaginal cuff closure and suture technique [28, 29].

Boosz and colleagues [7] reported a trend towards a higher overall re-operation rate after LSH procedures, with 2.7 % of patients undergoing CSE compared with 0.7 % of patients undergoing VCD after TLH. Van Evert et al. [6] reported a CSE rate of 2 % in 192 patients undergoing LSH.

No secondary CSEs due to unexpected histologic findings were necessary during the follow-up period in our study. In total, 3 (0.2 %) LSH patients reported spotting. By comparison, persistent vaginal bleeding was reported by 24 % of LSH patients after surgery [30].

VCD occurred in 2 (0.7 %) TLH patients, which is the same percentage as reported by Boosz et al. [7]. The two-layer suture technique is also advocated by other institutions. However, Jeung et al. [29] found no advantage of the two-layer running suture technique over the widely used figure-of-eight suture.

Contributing factors to lower the specific re-operation rate in LSH included extensive, almost complete removal of the cervix and the fact that TLH patients were strongly advised to refrain from sexual intercourse for at least 6–8 weeks.

Re-operation to perform laparoscopic adhesiolysis was necessary in 12 (0.6 %) patients [9 (0.5 %) LSH and 3 (1 %) TLH patients] in our study.

Predictive factors

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to generate models for predictive factors of conversion to laparotomy and complications based on logistic regression analysis of comparative data for LSH and TLH. Our data yielded reliable models for conversion and short-term complications. The final model for conversion showed that type of procedure (conversions being less likely with LSH than with TLH), uterine weight, and the necessity of minor or extensive adhesiolysis were statistically significant factors for conversion, whereas age at surgery was not. Interestingly, extensive adhesiolysis increased the odds of conversion whilst minor adhesiolysis reduced it.

The final model for predictive factors of short-term post-operative complications included age at surgery, type of procedure, and extensive adhesiolysis as statistically significant factors for short-term complications, whereas uterine weight and minor adhesiolysis were not statistically significant.

Predictive factors of intraoperative and long-term post-operative complications, unfortunately, were not reliably identifiable by logistic regression analysis due to small subgroup sizes in our study. Nevertheless, our calculations suggested that BMI might be a predictor of long-term post-operative complications.

Limitations of the study

A potential limitation of the study was its open, non-randomized design. Studies of this type are inevitably subject to potential patient and investigator biases (selection biases). The present study was not controlled for known or unknown confounders in study subjects. However, given that the decision whether to retain or remove the cervix was primarily indication- and guideline-based, randomization within a prospective design would have been a challenging and delicate endeavor if not ethically questionable. Another limitation is that despite the high return rate of 46.9 % of valid questionnaires, the actual number of long-term complications remained unknown, and an unknown percentage of patients may have undergone re-operation at other institutions.

Outlook: surgical and quality-of-life aspects

Further improvements in laparoscopic hysterectomy outcomes could be achieved in respect of surgical technique, quality of life, and patient satisfaction.

Surgically, patients at risk may benefit from concomitant preventive measures such as modified McCall culdoplasty sutures to mechanically support the vaginal vault and thus, prevent vaginal descensus and prolapse, and peritonealization to prevent the formation of adhesions.

Female sexual function is an important quality-of-life aspect, which was discussed with our patients during the pre-operative consent phase. Whilst according to a recent Cochrane review LSH does not offer improved sexual function outcomes compared with TAH [31], it remains to be investigated whether LSH compares favorably with TLH in respect of post-operative sexual function. Patient satisfaction with surgical treatment and the long-term outcome of surgery is essential to the success of any technique. We are currently conducting a long-term follow-up study in our cohort to address these specific aspects.

Lastly, the importance of a training and learning curve is illustrated by the observations of van Evert et al. regarding the association between surgeon experience and cervical problems. They found that vaginal bleeding was more likely to occur in patients operated on by less experienced surgeons (n < 50 procedures) [6]. A learning curve analysis of our data is currently underway.

Conclusions

Advantages of LSH over TLH include a significantly lower rate of conversion to laparotomy, shorter operating time, lower hemoglobin drop, and shorter hospital stay. This is indicative of faster recovery after LSH. Compared with TLH, LSH is the less invasive procedure and carries a significantly lower risk of short-term post-operative, total post-operative, and overall complications. LSH is associated with very low rates of re-operation and spotting.

We conclude that both methods proved safe and feasible in our experience. In the absence of an abnormal Pap smear or a history of HPV infection, patients eligible for LSH may be offered TLH as an alternative if they do not wish to retain the cervix after thorough pre-operative counseling about the possibility of cervical stump symptoms, which however were very rare in our experience. Importantly, we observed no cases of cervical cancer in our LSH patients.

After TLH, it is clinically essential that patients refrain from sexual intercourse for 6–8 weeks after surgery to avoid VCD.

The aspects of patient satisfaction and quality of life still await investigation. A study is currently underway aiming to correlate our surgical results with patient satisfaction and quality of life.

References

Sutton C (2010) Past, present, and future of hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 17(4):421–435. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2010.03.005

Jenkins TR (2004) Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 191(6):1875–1884. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.096

Mueller A, Renner SP, Haeberle L, Lermann J, Oppelt P, Beckmann MW, Thiel F (2009) Comparison of total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) and laparoscopy-assisted supracervical hysterectomy (LASH) in women with uterine leiomyoma. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 144(1):76–79. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.02.004

Kilkku P, Grönroos M, Hirvonen T, Rauramo L (1983) Supravaginal uterine amputation vs. hysterectomy. Effects on libido and orgasm. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 62(2):147–152

Thakar R, Ayers S, Clarkson P, Stanton S, Manyonda I (2002) Outcomes after total versus subtotal abdominal hysterectomy. N Engl J Med 347(17):1318–1325. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa013336

van Evert JS, Smeenk JMJ, Dijkhuizen FPHLJ, de Kruif JH, Kluivers KB (2010) Laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy versus laparoscopic total hysterectomy: a decade of experience. Gynecol Surg 7(1):9–12. doi:10.1007/s10397-009-0529-8

Boosz A, Lermann J, Mehlhorn G, Loehberg C, Renner SP, Thiel FC, Schrauder M, Beckmann MW, Mueller A (2011) Comparison of re-operation rates and complication rates after total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) and laparoscopy-assisted supracervical hysterectomy (LASH). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 158(2):269–273. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.04.021

Wallwiener D, Jonat W, Kreienberg R, Friese K, Diedrich K, Beckmann MW, Hirsch HA, Käser O, Ikle FA (2008) Atlas der gynäkologischen Operationen. Thieme, Stuttgart

Brucker S, Solomayer E, Zubke W, Sawalhe S, Wattiez A, Wallwiener D (2007) A newly developed morcellator creates a new dimension in minimally invasive surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 14(2):233–239. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2006.10.004

Greenberg JA (2010) Brucker/Messroghli Supraloop™ Unipolar Loop. Rev Obstet Gynecol 3(2):76–77

Bojahr B, Tchartchian G, Ohlinger R (2009) Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy: a retrospective analysis of 1,000 cases. JSLS 13(2):129–134

Bojahr B, Raatz D, Schonleber G, Abri C, Ohlinger R (2006) Perioperative complication rate in 1,706 patients after a standardized laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy technique. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 13(3):183–189. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2006.01.010

Grosse-Drieling D, Schlutius JC, Altgassen C, Kelling K, Theben J (2012) Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LASH), a retrospective study of 1,584 cases regarding intra- and perioperative complications. Arch Gynecol Obstet 285(5):1391–1396. doi:10.1007/s00404-011-2170-9

Hobson DT, Imudia AN, Al-Safi ZA, Shade G, Kruger M, Diamond MP, Awonuga AO (2012) Comparative analysis of different laparoscopic hysterectomy procedures. Arch Gynecol Obstet 285(5):1353–1361. doi:10.1007/s00404-011-2140-2

Wallenstein MR, Ananth CV, Kim JH, Burke WM, Hershman DL, Lewin SN, Neugut AI, Lu YS, Herzog TJ, Wright JD (2012) Effect of surgical volume on outcomes for laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign indications. Obstet Gynecol 119(4):709–716. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318248f7a8

Wattiez A, Soriano D, Cohen SB, Nervo P, Canis M, Botchorishvili R, Mage G, Pouly JL, Mille P, Bruhat MA (2002) The learning curve of total laparoscopic hysterectomy: comparative analysis of 1,647 cases. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 9(3):339–345

Tunitsky E, Citil A, Ayaz R, Esin S, Knee A, Harmanli O (2010) Does surgical volume influence short-term outcomes of laparoscopic hysterectomy? Am J Obstet Gynecol 203(1):24 e21–24 e26. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.070

Twijnstra AR, Blikkendaal MD, van Zwet EW, van Kesteren PJ, de Kroon CD, Jansen FW (2012) Predictors of successful surgical outcome in laparoscopic hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 119(4):700–708. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824b1966

Payne TN, Dauterive FR (2008) A comparison of total laparoscopic hysterectomy to robotically assisted hysterectomy: surgical outcomes in a community practice. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 15(3):286–291. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2008.01.008

Ghomi A, Cohen SL, Chavan N, Gunderson C, Einarsson J (2011) Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy vs laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy for treatment of non prolapsed uterus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 18(2):205–210. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2010.12.005

Warren L, Ladapo JA, Borah BJ, Gunnarsson CL (2009) Open abdominal versus laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy: analysis of a large United States payer measuring quality and cost of care. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 16(5):581–588. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2009.06.018

Lassen PD, Moeller-Larsen H, DEN P (2012) Same-day discharge after laparoscopic hysterectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 91(11):1339–1341. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01535.x

InEK GmbH (2012) Fallpauschalen-Katalog 2012. InEK GmbH. http://www.g-drg.de/cms/G-DRG-System_2012/Fallpauschalen-Katalog/Fallpauschalen-Katalog_2012. Accessed 18 Sept 2012

Mueller A, Boosz A, Koch M, Jud S, Faschingbauer F, Schrauder M, Löhberg C, Mehlhorn G, Renner SP, Lux MP, Beckmann MW, Thiel FC (2011) The Hohl instrument for optimizing total laparoscopic hysterectomy: results of more than 500 procedures in a university training center. Arch Gynecol Obstet 285(1):123–127. doi:10.1007/s00404-011-1905-y

Donnez O, Jadoul P, Squifflet J, Donnez J (2009) A series of 3,90 laparoscopic hysterectomies for benign disease from 1990 to 2006: evaluation of complications compared with vaginal and abdominal procedures. BJOG 116(4):492–500. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01966.x

Malzoni M, Perniola G, Perniola F, Imperato F (2004) Optimizing the total laparoscopic hysterectomy procedure for benign uterine pathology. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 11(2):211–218

McCartney AJ, Obermair A (2004) Total laparoscopic hysterectomy with a transvaginal tube. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 11(1):79–82

Iaco PD, Ceccaroni M, Alboni C, Roset B, Sansovini M, D’Alessandro L, Pignotti E, Aloysio DD (2006) Transvaginal evisceration after hysterectomy: is vaginal cuff closure associated with a reduced risk? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 125(1):134–138. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.08.009

Jeung IC, Baek JM, Park EK, Lee HN, Kim CJ, Park TC, Lee YS (2010) A prospective comparison of vaginal stump suturing techniques during total laparoscopic hysterectomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 282(6):631–638. doi:10.1007/s00404-009-1300-0

Lieng M, Lomo AB, Qvigstad E (2010) Long-term outcomes following laparoscopic and abdominal supracervical hysterectomies. Obstet Gynecol Int 2010:989127. doi:10.1155/2010/989127

Lethaby A, Ivanova V, Johnson NP (2006) Total versus subtotal hysterectomy for benign gynaecological conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD004993. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004993.pub2

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sandra Ebersoll, Christian W. Wallwiener, and Adam Kasperkowiak for excellent technical assistance. No financial support or funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interest

All authors were employees of their respective university hospital. SYB was actively involved in the development of the SupraLoop™ unipolar loop for LSH. None of the authors have any financial relationships with instrument or equipment manufacturers or other commercial interests that might represent potential conflicts of interest regarding this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wallwiener, M., Taran, FA., Rothmund, R. et al. Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LSH) versus total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH): an implementation study in 1,952 patients with an analysis of risk factors for conversion to laparotomy and complications, and of procedure-specific re-operations. Arch Gynecol Obstet 288, 1329–1339 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-013-2921-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-013-2921-x