Abstract

Objective

This study aimed at determining trends, risk factors and pregnancy outcome in women with uterine rupture.

Methods

A population-based study, comparing all singleton deliveries with and without uterine rupture between 1988 and 2009 was conducted. Statistical analysis was performed using a multiple logistic regression analysis.

Results

Uterine rupture occurred in 0.06% (n = 138) of all deliveries included in the study (n = 240,189); 59% in women with a previous cesarean delivery (CD). A gradual increase in the rate of uterine rupture from 1988 (0.01%) to 2009 (0.05%) was noted. Independent risk factors for uterine rupture in a multivariable analysis were: previous CD (OR = 7.4, 95% CI 5.2–10.6), preterm delivery (<37 weeks, OR = 2.5, 95% CI 1.5–4.1), malpresentation (OR = 3.0, 95% CI 1.9–4.5), parity (OR = 1.2, 95% CI 1.1–1.3 for each birth), and dystocia during the first and second stages of labor (OR = 4.1, 95% CI 2.3–7.4 and OR = 11.2, 95% CI 6.7–18.7, respectively). Uterine rupture led to significant maternal morbidity and perinatal mortality. In another multivariable analysis, with perinatal mortality as the outcome variable uterine rupture was noted as an independent risk factor for perinatal mortality (adjusted OR = 17.7; 95% CI 10.0–31.4, P < .01).

Conclusions

Uterine rupture, associated with previous cesarean delivery, malpresentation, and labor dystocia, is an independent risk factor for perinatal mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Uterine rupture is an obstetric emergency, which threatens the life of both the mother and the newborn [1–4]. It is associated with postpartum hemorrhage [1, 3], need for blood transfusion [3, 4] and hysterectomy [1, 3, 4]. Newborns to mothers suffering from uterine rupture are graded lower on their 1- and 5-min Apgar scores [2, 3] and are at higher risk for peripartum death [2–4]. It is a relatively rare condition whose incidence varies between 1 in 1,096 deliveries [2] and 1 in 2,900 deliveries [3]. Accordingly, most publications included a small number of cases from a single medical center. In the last couple of years, there were several studies with larger population of 210 cases [4] or 274 cases [2] although they were based on a multi-center database.

The major risk factor for uterine rupture is previous cesarean delivery (CD) [2–4]. Other risk factors identified as contributing to uterine rupture are malpresentations [3], second stage dystocia [3, 5], labor induction [2, 4, 6, 7], use of epidural for pain control [4, 8], preterm delivery [4] and delivery after the 42nd week of gestation [2, 4]. On the other hand, a successful vaginal birth after CD was found to reduce the risk for uterine rupture in subsequent deliveries [6, 9] as well as a vaginal labor before the primary CD [6, 10].

Recent publications show various trends in obstetric phenomena. The incidence of CD has been significantly increased [11, 12]. One study showed an increased incidence of peripartum hysterectomy [13], and another reported an increase in the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage [14]. The present study was aimed to assess risk factors for uterine rupture as well as trends in the incidence of this significant complication along the years in a single tertiary medical center.

Methods

Our study included all 240,189 singleton deliveries at the Soroka University Medical Center between January 1988 and December 2009. Data were obtained from a perinatal database consisting of information recorded immediately after each delivery by an obstetrician. Soroka University Medical Center is the only hospital in the Negev, the southern part of Israel, and therefore contains its entire obstetric population.

Information was recorded from all patients regarding demographic and clinical characteristics including: maternal age, gravidity, parity, gestational age, birth weight and neonatal gender. The following obstetric risk factors were recorded: previous CD, hypertensive disorders, diabetes mellitus, polyhydramnios [amniotic fluid index (AFI) >24 cm], oligohydramnios (AFI <5 cm), and premature rupture of membranes (PROM). The following pregnancy and labor complications were evaluated: labor induction by Foley catheter, early amniotomy, oxytocin or prostaglandin E2; oxytocin augmentation in general; epidural analgesia, malpresentation, dystocia during the first and second stages of labor, non-reassuring fetal heart rate (FHR) patterns, cephalopelvic disproportion, breech delivery, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and caesarean delivery. The following birth and neonatal outcomes were assessed: postpartum hemorrhage, blood transfusion, cervical tears, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min <5, and perinatal mortality.

A delivery was considered as complicated with uterine rupture according to the ICD9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification) for “uterine rupture” 665.11. The diagnosis was done by the attending physician. We regarded only cases of complete uterine rupture.

To test the statistical significance of categorical variables, chi square and fisher’s exact test were used as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA). In order to assess independent risk factors for uterine rupture and to control for potential confounders a multiple logistic regression model was used. Odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% CI were calculated from the model. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

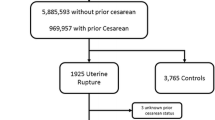

Uterine rupture occurred in 0.06% (n = 138) of all deliveries included in our study (n = 240,189). The incidence of uterine rupture gradually increased from 1988 (0.01%) to 2009 (0.05%; Fig. 1). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 1. There were statistically significant differences in the maternal age, gestational age (in weeks) and birth weight. No significant difference was found in neonatal gender. Women with high parity and gravidity had a significantly higher risk for uterine rupture.

The presence of obstetric risk factors in women with and without uterine rupture is compared in Table 2. Previous CD and hypertensive disorders occurred in significantly higher rates among women with uterine rupture. The probability of uterine rupture within the women who undergone CD (n = 28,657; 11.9%) was 0.28% compared with 0.03% in the group of women that did not have a history of CD (n = 211,532; 88.1%).

Pregnancy and labor complications are presented in Table 3. Malpresentation, cephalopelvic disproportion, dystocia during the first or second stages of labor and non-reassuring FHR patterns were seen in significantly higher rates in the group complicated with uterine rupture. In addition, breech deliveries and CD were significantly more frequent among this group.

Table 4 shows the birth and pregnancy outcome in pregnancies of women with and without uterine rupture. Women who suffered from uterine rupture had significantly higher rates of postpartum hemorrhage, cervical tears and needed more blood transfusions. In addition, neonates born following uterine rupture had higher rates of low Apgar scores (lower than 5) after 1 and 5 min and had higher rates of perinatal mortality.

Independent risk factors for uterine rupture in a multivariable analysis were previous CD, preterm delivery, malpresentation, parity and dystocia during the first and second stages of labor (Table 5). Another multivariable analysis with perinatal mortality as an outcome variable was constructed in order to control for confounders such as maternal age, gestational age, etc. Uterine rupture was found as an independent risk factor for perinatal mortality (adjusted OR = 17.73, 95% CI 9.99–31.41, P value < 0.001; data not shown in a Table).

Discussion

Uterine rupture is a significant complication. While the incidence of uterine rupture found in this study (0.06%) was similar to previous studies, a temporal increase in the incidence throughout the years was documented. Nevertheless, the relative peak in 2006 is not clear since no changes in guidelines occurred during this year. Undoubtedly, a major contribution to this trend could be related to the markedly increase in the rate of CD over these years [11, 12].

Uterine rupture was associated with significant maternal and neonatal morbidity. As was previously documented [2–4], uterine rupture was associated with Apgar scores lower than 5 at 1 and 5 min and perinatal mortality, and was actually noted as an independent risk factor for perinatal mortality. The relatively large sample size (to the best of our knowledge, one of the largest published from a single medical center), abled us to confirm several independent risk factors for uterine rupture. Such risk factors included: previous CD, dystocia during the first or second stage of labor, malpresentation, preterm delivery and high parity. Some of the characteristics that were not identified as independent risk factors could have been statistically significant due to the large sample size.

Several studies found labor induction as an important risk factor for uterine rupture [2, 4, 6, 7]. Interestingly, while investigating independent risk factors for uterine rupture, labor induction was not labeled as an independent risk factor for uterine rupture, supporting the findings of Ouzounian et al. [15], which evaluated the incidence of uterine rupture among women receiving labor induction for vaginal birth after CD.

Use of epidural analgesia during the labor did not seem to increase the rate of uterine rupture, unlike previous reports [4]. Cahill et al. [8] did not find significant difference regarding the entire study population although in cox regression analysis they found a dose–response ratio between the number of epidural doses and the risk for uterine rupture.

In conclusion, uterine rupture, associated with previous CD, dystocia during the first and second stages of labor, malpresentation, preterm delivery and parity, is an independent risk factor for perinatal mortality. It is a rare obstetric complication without a specific factor that can efficiently predict it [6]. As the rate of CD is rising, more women would arrive at birth with a scarred uterus, exposing them to a higher risk for uterine rupture. In order to avoid its grave consequences, the diagnosis of uterine rupture should be taken into account, specifically when additional risk factors exist.

References

Al-Zirqi I, Stray-Pedersen B, Forsén L, Vangen S (2010) Uterine rupture after previous caesarean section. BJOG 117(7):809–820

Kaczmarczyk M, Sparén P, Terry P, Cnattingius S (2007) Risk factors for uterine rupture and neonatal consequences of uterine rupture: a population-based study of successive pregnancies in Sweden. BJOG 114(10):1208–1214

Ofir K, Sheiner E, Levy A, Katz M, Mazor M (2003) Uterine rupture: risk factors and pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189(4):1042–1046

Zwart JJ, Richters JM, Ory F, De Vries JI, Bloemenkamp KW, Van Roosmalen J (2009) Uterine rupture in the Netherlands: a nationwide population-based cohort study. BJOG 116(8):1069–1078

Hamilton EF, Bujold E, McNamara H, Gauthier R, Platt RW (2001) Dystocia among women with symptomatic uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol 184(4):620–624

Grobman WA, Lai Y, Landon MB et al (2008) Prediction of uterine rupture associated with attempted vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 199(1):30.e31–30.e35

Dekker G, Chan A, Luke C, Priest K, Riley M, Halliday J, King J, Gee V, O’Neill M, Snell M, Cull V, Cornes S (2010) Risk of uterine rupture in Australian women attempting vaginal birth after one prior caesarean section: a retrospective population-based cohort study. BJOG 117(11):1358–1365

Cahill AG, Odibo AO, Allsworth JE, Macones GA (2010) Frequent epidural dosing as a marker for impending uterine rupture in patients who attempt vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 202(4):355.e351–355.e355

Zelop CM, Shipp TD, Repke JT, Cohen A, Lieberman E (2000) Effect of previous vaginal delivery on the risk of uterine rupture during a subsequent trial of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183(5):1184–1186

Algert CS, Morris JM, Simpson JM, Ford JB, Roberts CL (2008) Labor before a primary cesarean delivery: reduced risk of uterine rupture in a subsequent trial of labor for vaginal birth after cesarean. Obstet Gynecol 112(5):1061–1066

Menacker F, Hamilton BE (2010) Recent trends in cesarean delivery in the United States. NCHS data brief, no 35. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD

Guise JM, Denman MA, Emeis C, Marshall N, Walker M, Fu R, Janik R, Nygren P, Eden KB, McDonagh M (2010) Vaginal birth after cesarean: new insights on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol 115(6):1267–1278

Orbach A, Levy A, Wiznitzer A, Mazor M, Holcberg G, Sheiner E (2010) Peripartum cesarean hysterectomy: critical analysis of risk factors and trends over the years. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 24(3):480–484

Callaghan WM, Kuklina EV, Berg CJ (2010) Trends in postpartum hemorrhage: United states, 1994–2006. Am J Obstet Gynecol 202(353):e1–e6

Ouzounian JG, Miller DA, Hiebert CJ, Battista LR, Lee RH (2011) Vaginal birth after cesarean section: risk of uterine rupture with labor induction. Am J Perinatol (epub ahead of print)

Acknowledgment

Performed in part of Dror Ronel MD requirements.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no declaration of interest, and no conflict of interest exists.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ronel, D., Wiznitzer, A., Sergienko, R. et al. Trends, risk factors and pregnancy outcome in women with uterine rupture. Arch Gynecol Obstet 285, 317–321 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-011-1977-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-011-1977-8