Abstract

Melanoma-screening examinations support early diagnosis, yet there is a national shortage of dermatologists and most at-risk patients lack access to dermatologic care. Primary care physicians (PCPs) in the United States often bridge these access gaps, and thus, play a critical role in the early detection of melanoma. However, most PCPs do not offer skin examinations. We conducted a systematic review and searched Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library from 1946 to July 2019 to identify barriers for skin screening by providers, patients, and health systems following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline. Of 650 abstracts initially identified, 111 publications were included for full-text review and 48 studies met the inclusion criteria. Lack of dermatologic training (89.4%), time constraints (70%), and competing comorbidities (51%) are the most common barriers reported by PCPs. Low perceived risk (69%), long delays in appointment (46%), and lack of knowledge about melanoma (34.8%) are most frequently reported patient barriers. Qualitative reported barriers for health system are lack of public awareness, social prejudice leading to tanning booth usage, public surveillance programs requiring intensive resources, and widespread ABCD evaluation causing delays in seeking medical attention for melanomas. Numerous barriers remain that prevent the implementation of skin screening practices in clinical practice. A multi-faceted combination of efforts is essential for the execution of acceptable and effective skin cancer-screening practices, thus, increasing early diagnosis and lowering mortality rates and burden of disease for melanoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Melanoma is the fifth most common cancer in the US [3], responsible for an estimated $3.5 billion annual productivity loss due to melanoma mortality [4]. Secondary prevention (i.e., early detection) offers particular opportunity for melanoma, as early diagnosis is associated with low melanoma mortality [5] and visual examination to detect melanoma is one of the most rapid, safe and cost-effective interventions in medicine [6]. While areas with higher dermatology density demonstrate lower melanoma mortality [7], dermatologist density is disproportionately concentrated in urban areas, resulting in low access to dermatology care in medically underserved areas [8]. In these under-resourced areas, primary care providers (PCPs) have an opportunity to perform skin examinations to support early melanoma diagnosis [9, 10].

Despite potential benefits to early melanoma detection, barriers to skin examinations exist at the patient, provider, and health system levels. Identifying barriers and potential approaches to surmounting those barriers is an important step in developing, implementing, and disseminating early melanoma detection programs. Defining current skin examination practices among PCPs is challenging: 8–20% of patients report receiving skin examinations from their PCP [11, 12], while PCPs report performing skin examinations in 31–60% of patient encounters [10, 13, 14]. The INternet curriculum FOR Melanoma Early Detection (INFORMED), developed by a multidisciplinary team specifically to support PCP performance of skin examinations, generated improved confidence and diagnostic accuracy among those completing the program [15]. However, qualitative post-session discussions highlighted the reluctance of PCPs to proceed with practice change and integrate skin examinations into patient care, citing the need for additional education and provision of assistance with challenging cases encountered in practice [16].

Designing feasible, acceptable and cost-effective implementation strategies to optimize access to diagnostic skin cancer encounters requires identifying barriers to performing skin cancer diagnostic examinations among PCPs, requesting and accepting examinations among patients [2], and supporting examinations from healthcare systems [17]. We present a systematic literature review of documented barriers to skin cancer examinations experienced by primary care providers, patients, and health systems.

Methods

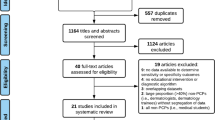

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines [18]. Eligibility criteria included: studies that addressed quantitative and qualitative data regarding barriers for skin cancer-screening or diagnostic examinations by providers (physicians and advanced practice providers [i.e., Nurse Practitioners (NPs) and Physician Assistants (PAs)], patients or health systems. Publications were not limited by geography. The following bibliographic databases were searched from 1946 through July 10, 2019: MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The inclusion criteria included publication dates between January 1, 1990, and July 10, 2019 to present the most current and relevant studies, availability of full text in the English language and mention of at least one skin cancer-screening barrier in the full-text article. A medical librarian (D.P.F) developed and tested search strategies with input from our lead authors (M.N. and K.C.N). The search strategies contained a combination of controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH or Emtree) and keyword terms to identify articles concerning skin cancer diagnostic examination barriers (Supplemental Table S1). The ability of the preliminary search strategies to achieve a pool of known, relevant citations tested search sensitivity. An EndNote library was created for managing the retrieved records and for de-duplication. Figure 1 demonstrates the study selection process for the final 48 publications selected for inclusion according to the PRISMA guidelines.

Study characteristics data were extracted and coded, including the including cohort from which barriers were identified, specific identified barriers, and the presence or absence of quantitative data. All identified barriers were assessed using thematic analysis to group barrier themes; quantitatively coded barriers were grouped based on identified themes with application of heatmap-based coding to identify relative barrier frequency across studies.

Results

We identified 650 records through database searches and 8 records through other sources. After removal of 90 duplicate records, two authors (M.N. and K.C.N.) analyzed the remaining 568 records independently and excluded 456 records on basis of title and abstract review. In the event of differences, consensus was reached through discussion. One hundred and twelve full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and of these 112 articles, 64 were excluded after a single reviewer evaluation (M.N.).

The 48 publications selected for inclusion were classified as: (1) 28 publications addressing patient barriers alone [1, 2, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]; (2) 10 publications addressing physician barriers alone [10, 13, 16, 17, 45,46,47,48,49,50]; (3) 3 publications addressing both physician and patient barriers [14, 51, 52]; (4) 1 publication addressing physician and public health barriers [53]; (5) 1 publication addressing barriers for patients, physicians, and public health [54]; and (6) 5 publications addressing barriers for advanced practice providers (4 NP [55,56,57,58] and 1 PA [59]).

Most of the included publications were structured as qualitative surveys conducted online, in person, or via telephone or mail. Our review includes responses from at least 8967 patients, 2775 PCPs, and 922 APPs. Fishbone diagrams of all qualitatively or quantitatively described barriers are provided for PCPs (Fig. 2a), APPs (Fig. 2b), patients (Fig. 2c), and health systems (Fig. 2d). Among quantitatively reported barriers the three most frequently cited provider PCP (Table 1a) and APP (Table 1b) barriers to skin cancer diagnostic examinations include: time constraints, competing patient comorbidities, and lack of training in skin cancer diagnostic examinations. The three most frequently cited patient barriers (Table 1c) include: lack of knowledge, low perceived risk, and long delays in obtaining an appointment. Only four public health barriers were identified: lack of public awareness, social prejudice leading to tanning booth usage, public surveillance programs requiring intensive resources, and widespread ABCD evaluation causing delays in seeking medical attention for melanomas that do not meet the ABCD criteria.

a Fishbone diagram of barriers to PCP performance of skin cancer-screening examinations. b Fishbone diagram of barriers to advanced practice provider (APP) performance of skin cancer-screening examinations. c Fishbone diagram of patient barriers to receiving skin cancer-screening examinations. d Fishbone diagram of public health-based barriers to skin cancer-screening examinations

Discussion

Based on data analysis from 48 publications, our systematic review enumerates myriad barriers to skin cancer diagnostic examinations for both patients and providers. Identifying and defining these barriers will inform the development of multilayered approaches to facilitate early melanoma-screening initiatives.

The existence of barriers to PCPs performing skin cancer screenings is not unexpected as PCPs provide front-line health care for millions of patients [60]. However, the front-line service simultaneously offers enormous opportunity for access to diagnostic skin cancer examinations [53]. Time constraints, competing patient comorbidities, and lack of training in performing skin cancer-screening examinations were the most frequently reported barriers for both PCPs and APPs. Time constraints can be alleviated by clinical operations-based implementations, including pre-emptive identification of patients eligible for skin examinations and a structured plan to introduce the examination concept and prepare the patient to minimize provider delays. An Integrated Skin Examination approach, with examination of the skin coordinated with other planned diagnostic physical actions, can minimize additional provider examination time, while facilitating structured examination of the skin [61]. Competing comorbidities is a significant barrier for PCPs as they manage patients with multiple active medical conditions; prioritizing diagnostic skin examinations for patients at the highest risk of melanoma mortality (Caucasian men older than 50 years) can focus examination efforts to the patient cohort likely to experience the greatest benefit and reduce provider burden [60].

Insufficient diagnostic aptitude for skin cancer may be mitigated through provider educational interventions such as INFORMED [16], Visual Perception Training [62], and mastery level training [63]. While all interventions generate improved knowledge and diagnostic accuracy among participants, unless providers also achieve appropriate self-efficacy in their newly acquired skill, they are unlikely to incorporate skin cancer diagnostic examinations into practice, thus, limiting direct patient benefit.

The three most frequently cited patient barriers to skin examinations included lack of knowledge, low perceived risk, and long delays in obtaining appointments for evaluation. PCPs can mitigate patient-based lack of knowledge and low perceived risk through providing office-based information on melanoma risk factors and examination procedures; this information may also address patient embarrassment, another frequently reported patient barrier [23,24,25, 29]. In one study, family (spouse or children) and relatives identified 50% of self-detected melanomas and provided encouragement to seek medical attention, supporting a potential role for general population education to improve overall detection of melanoma [37]. Awareness and risk campaigns targeting adult patients and family members can be accomplished through radio, television, and newspaper interventions [32], and social media platforms such as Instagram can be used to target adolescents and young adults [64]. Excessive waiting times to receive skin cancer diagnostic examinations by dermatologists were another frequently reported barrier [30]; PCP educational interventions have the opportunity to increase access to skilled diagnostic examinations.

Public health efforts to enhance melanoma awareness may empower patients to correctly identify and seek medical attention for melanoma at more curable stages [44]. Public awareness and advocacy campaigns that highlight skin cancer risks, targeted to high-risk patients (and their families) [37, 39, 60], with a suggested action of requesting PCP examination of concerning skin lesions [10] may offer the greatest mortality benefit. Public melanoma surveillance programs, such as the SCREEN study in Germany, have demonstrated the feasibility of skin cancer screening to detect melanomas at treatable stages [65]. However, this benefit must be balanced by the resources required to fund intensive initiatives, potentially through efforts to target specific high-risk patient demographics [37, 43]. Reduced exposure of young adults to tanning beds can be accomplished both through health policy interventions to mitigate social expectations of beauty, similar to efforts of the tobacco health policy movement, and through public policy interventions [54]. Finally, public melanoma awareness campaigns have been fairly directed to the ABCD warning signs: Asymmetry, irregular Border, multiple Colors, and Diameter more than 6 mm, respectively. These criteria, however, may prompt false reassurance for nodular (frequently presents as a smooth-bordered, single-colored papule, with high metastatic potential even at diameters < 6 mm) and amelanotic (clinically subtle tumors with pink/light brown pigmentation) melanomas. Therefore, any new or changing skin growth should prompt patients to request physician evaluation regardless of whether the growth meets the ABCD criteria [53].

Limitations

As with most systematic reviews, the main limitation of this review is the quality of published data. Other limitations are choice and number of databases used and the proper use of all potential keywords. Therefore, high-quality publications addressing our topic may have been inadvertently excluded from the search strategy. Possible biases include language bias (we utilized full-text articles available in the English language) and the inclusion of studies with methodological bias (possibility of sampling and selection bias during original research study). As researcher influence inherently impacts the analysis of qualitative data, participant-reported data are subject to reviewer interpretation (original authors and ours), introducing potential risk for misinterpretation. There was somewhat limited reporting of quantitative data: many studies only qualitatively identified barriers and quantitative data did not always quantify the relative effects of barriers or the number of respondents citing specific barriers as being of concern. Finally, barriers were assessed in different health systems, including the US, Germany, France, and Australia; given the varied respective sociocultural and economic backgrounds, barriers may not translate across international health systems.

Conclusion

Melanoma diagnosed at advanced stages demonstrates a strong propensity for metastatic spread; while immunotherapy and targeted therapies have reduced global melanoma mortality, these interventions are not without significant financial burden and risk of therapeutic adverse events. Conversely, melanoma diagnosed at early stages carries the potential for cure with a straight-forward therapeutic excision, yet access to skilled diagnostic examinations can be challenging in areas of low dermatology density. PCPs have the potential to serve as critical melanoma detection resources in regions without dermatology access, yet the 2016 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Updated Systematic Evidence Review for Screening for Skin Cancer in Adults [66] states “the current evidence is insufficient to assess the benefits and harms of using a whole-body skin examination by a primary care clinician”. The USPSTF recognizes evidence to be adequate that skin screening examinations have modest sensitivity and specificity for detection of melanoma, and early detection by a clinician reduces morbidity and mortality. However, the potential for harm, such as misdiagnosis, overdiagnosis, and cosmetic adverse effects from biopsy and potential overtreatment, warrants further research.

Future early melanoma detection initiatives can address the evidence gaps as highlighted by the USPSTF’s assessment but must be structured based on a firm understanding of the barriers to skilled diagnostic examinations encountered by providers, patients, and public health systems. Supporting providers in developing and sustaining skilled diagnostic examination skills will mitigate potential patient harm by reducing benign biopsies performed to identify one melanoma (quantified as the number needed to biopsy, or NNB [67]). More clearly defining the enhanced risk cohort for targeted screening will help focus patient and family awareness messaging, while reducing the screening burden for PCPs, and enhancing the incidence rate for the screened population, also resulting in fewer benign biopsies and fewer patients screened to identify one melanoma [60]. A multi-faceted combination of efforts is essential for the implementation of acceptable and effective skin cancer-screening practices thus increasing early diagnosis and lowering mortality rates and burden of disease for melanoma.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Mendely data at URL: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/x3bdz66w7s/draft?a=40da4e93-a33b-452b-925e-45896d674456.

References

Gorig T et al (2018) Barriers to using a nationwide skin cancer screening program: findings from Germany. Oncol Res Treat 41(12):774–779

McWhirter JE, Hoffman-Goetz L (2016) Application of the health belief model to us magazine text and image coverage of skin cancer and recreational tanning (2000–2012). J Health Commun 21(4):424–438

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2018) Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 68(1):7–30

Ekwueme DU et al (2011) The health burden and economic costs of cutaneous melanoma mortality by race/ethnicity-United States, 2000 to 2006. J Am Acad Dermatol 65(5 Suppl 1):S133–S143

Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA (2018) Melanoma staging: American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition and beyond. Ann Surg Oncol 25(8):2105–2110

Riker AI, Zea N, Trinh T (2010) The epidemiology, prevention, and detection of melanoma. Ochsner J 10(2):56–65

Aneja S, Aneja S, Bordeaux JS (2012) Association of increased dermatologist density with lower melanoma mortality. Arch Dermatol 148(2):174–178

Glazer AM, Rigel DS (2017) Analysis of trends in geographic distribution of US dermatology workforce density. JAMA Dermatol 153(5):472–473

Friedman KP et al (2004) Melanoma screening behavior among primary care physicians. Cutis 74(5):305–311

Geller AC et al (2004) Overcoming obstacles to skin cancer examinations and prevention counseling for high-risk patients: results of a national survey of primary care physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract 17(6):416–423

Geller AC et al (1992) Use of health services before the diagnosis of melanoma: implications for early detection and screening. J Gen Intern Med 7(2):154–157

LeBlanc WG et al (2008) Reported skin cancer screening of US adult workers. J Am Acad Dermatol 59(1):55–63

Kirsner RS, Muhkerjee S, Federman DG (1999) Skin cancer screening in primary care: prevalence and barriers. J Am Acad Dermatol 41(4):564–566

Oliveria SA et al (2011) Skin cancer screening by dermatologists, family practitioners, and internists: barriers and facilitating factors. Arch Dermatol 147(1):39–44

Eide MJ et al (2013) Effects on skills and practice from a web-based skin cancer course for primary care providers. J Am Board Fam Med 26(6):648–657

Jiang AJ et al (2017) Providers’ experiences with a melanoma web-based course: a discussion on barriers and intentions. J Cancer Educ 32(2):272–279

Wender RC (1995) Barriers to effective skin cancer detection. Cancer 75(2 Suppl):691–698

Moher D et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097

Bergenmar M, Tornberg S, Brandberg Y (1997) Factors related to non-attendance in a population based melanoma screening program. Psychooncology 6(3):218–226

Claudio C et al (2007) Cancer screening participation: comparative willingness of San Juan Puerto Ricans versus New York city Puerto Ricans. J Natl Med Assoc 99(5):542–549

Douglass HM, McGee R, Williams S (1998) Are young adults checking their skin for melanoma? Aust N Z J Public Health 22(5):562–567

Eiser JR et al (2000) Is targeted early detection for melanoma feasible? Self assessments of risk and attitudes to screening. J Med Screen 7(4):199–202

Federman DG et al (2006) Full-body skin examinations and the female veteran: prevalence and perspective. Arch Dermatol 142(3):312–316

Federman DG et al (2008) Patient gender affects skin cancer screening practices and attitudes among veterans. South Med J 101(5):513–518

Federman DG et al (2004) Full body skin examinations: the patient’s perspective. Arch Dermatol 140(5):530–534

Fitzpatrick L, Hay JL (2014) Barriers to risk-understanding and risk-reduction behaviors among individuals with a family history of melanoma. Melanoma Manag 1(2):185–191

Heckman CJ et al (2013) Correspondence and correlates of couples’ skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol 149(7):825–830

Hennrikus D et al (1991) A community study of delay in presenting with signs of melanoma to medical practitioners. Arch Dermatol 127(3):356–361

Janda M et al (2004) Prevalence of skin screening by general practitioners in regional Queensland. Med J Aust 180(1):10–15

Lam K et al (2019) Skin cancer screening after solid organ transplantation: survey of practices in Canada. Am J Transplant 19(6):1792–1797

Lee G et al (1991) Yield from total skin examination and effectiveness of skin cancer awareness program. Findings in 874 new dermatology patients. Cancer 67(1):202–205

McMichael AJ, Jackson S (1998) Who comes to a skin cancer screening–and why? N C Med J 59(5):294–297

Oliveria SA et al (1999) Patient knowledge, awareness, and delay in seeking medical attention for malignant melanoma. J Clin Epidemiol 52(11):1111–1116

Rat C et al (2017) Anxiety, locus of control and sociodemographic factors associated with adherence to an annual clinical skin monitoring: a cross-sectional survey among 1000 high-risk French patients involved in a pilot-targeted screening programme for melanoma. BMJ Open 7(10):e016071

Rat C et al (2015) Melanoma incidence and patient compliance in a targeted melanoma screening intervention. One-year follow-up in a large French cohort of high-risk patients. Eur J Gen Pract 21(2):124–130

Rat C et al (2014) Patients at elevated risk of melanoma: individual predictors of non-compliance to GP referral for a dermatologist consultation. Prev Med 64:48–53

Richard MA et al (2000) Delays in diagnosis and melanoma prognosis (I): the role of patients. Int J Cancer 89(3):271–279

Ridolfi DR, Crowther JH (2013) The link between women’s body image disturbances and body-focused cancer screening behaviors: a critical review of the literature and a new integrated model for women. Body Image 10(2):149–162

Schmid-Wendtner MH et al (2002) Delay in the diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma: an analysis of 233 patients. Melanoma Res 12(4):389–394

Walter FM et al (2010) Patient understanding of moles and skin cancer, and factors influencing presentation in primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 11:62

Youl PH et al (2006) Who attends skin cancer clinics within a randomized melanoma screening program? Cancer Detect Prev 30(1):44–51

Zink A et al (2018) Primary and secondary prevention of skin cancer in mountain guides: attitude and motivation for or against participation. JEADV 32(12):2153–2161

Zink A et al (2017) Do outdoor workers know their risk of NMSC? Perceptions, beliefs and preventive behaviour among farmers, roofers and gardeners. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 31(10):1649–1654

Zhang, S., et al. (2019) Thick melanoma is associated with low melanoma knowledge and low perceived health competence, but not delays in care. J Am Acad Dermatol

Curiel-Lewandrowski C, Swetter SM (2016) Lack of harms from community-based melanoma screening by primary care providers. Cancer 122(20):3102–3105

Divito SJ, Ferris LK (2010) Advances and short comings in the early diagnosis of melanoma. Melanoma Res 20(6):450–458

Herath H et al (2018) Knowledge, attitudes and skills in melanoma diagnosis among doctors: a cross sectional study from Sri Lanka. BMC Res Notes 11(1):389

Kirsner RS, Federman DG (1998) The rationale for skin cancer screening and prevention. Am J Manag Care 4(9):1279–1284

Tucunduva LT et al (2004) Evaluation of non-oncologist physician’s knowledge and attitude towards cancer screening and preventive actions. Rev Assoc Med Bras 50(3):257–262

Wise E et al (2009) Rates of skin cancer screening and prevention counseling by US medical residents. Arch Dermatol 145(10):1131–1136

Chung GY, Brown G, Gibson D (2015) Increasing melanoma screening among hispanic/latino Americans: a community-based educational intervention. Health Educ Behav 42(5):627–632

Federman DG, Kirsner RS, Viola KV (2013) Skin cancer screening and primary prevention: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol 31(6):666–670

Weinstock MA (2006) Cutaneous melanoma: public health approach to early detection. Dermatol Ther 19(1):26–31

Torrens R, Swan BA (2009) Promoting prevention and early recognition of malignant melanoma. Dermatol Nurs 21(3):115–123

Furfaro T et al (2008) Nurse practitioners’ knowledge and practice regarding malignant melanoma assessment and counseling. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 20(7):367–375

Maguire-Eisen M, Frost C (1994) Knowledge of malignant melanoma and how it relates to clinical practice among nurse practitioners and dermatology and oncology nurses. Cancer Nurs 17(6):457–463

Roebuck H (2015) Assessing skin cancer prevention and detection educational needs. J Nurse Pract 11(4):409–416

Shelby DM (2014) Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of primary care nurse practitioners regarding skin cancer assessmnets validity and reliability of a new instrument. University of South Florida

Haley AC et al (2012) Melanoma opportunistic surveillance by physician assistant and medical students: analysis of a novel educational trainer. J Physician Assist Educ 23(4):6–15

Garg A, Geller A (2011) Need to improve skin cancer screening of high-risk patients: comment on “skin cancer screening by dermatologists, family practitioners, and internists.” Arch Dermatol 147(1):44–45

Garg A et al (2014) The integrated skin exam film: an educational intervention to promote early detection of melanoma by medical students. J Am Acad Dermatol 70(1):115–119

Choi AW et al (2019) Visual perception training: a prospective cohort trial of a novel, technology-based method to teach melanoma recognition. Postgrad Med J 95(1124):350–352

Robinson JK et al (2018) A randomized trial on the efficacy of mastery learning for primary care provider melanoma opportunistic screening skills and practice. J Gen Intern Med 33(6):855–862

Basch, C.H. and G.C. Hillyer (2020) Skin cancer on Instagram: implications for adolescents and young adults. Int J Adolesc Med Health

Waldmann A et al (2012) Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany–an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer 106(5):970–974

Force USPST et al (2016) Screening for skin cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 316(4):429–435

Nelson, K.C., et al. (2019) Evaluation of the number-needed-to-biopsy metric for the diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol

Acknowledgements

Laura Cortina, Research Data Coordinator, University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center assisted with formatting of fishbone diagram figures.

Funding

This project is supported by the generous philanthropic contributions of the Lyda Hill Foundation to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Moon Shots Program™, and NCI R25E grant, MD Anderson.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MN: data collection and writing the manuscript. AEB: editing. SRH: data collection. DF: literature search. SS: reviewing. KCN: principal investigator, data collection, writing, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Najmi, M., Brown, A.E., Harrington, S.R. et al. A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative and quantitative studies evaluating provider, patient, and health care system-related barriers to diagnostic skin cancer examinations. Arch Dermatol Res 314, 329–340 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-021-02224-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-021-02224-z