Abstract

Objective

The objective of the current study was to evaluate the effect of a quality management system on treatment and care delivery of proximal femoral fractures. Specifically, our hypothesis was that the “plan–do–check–act (PDCA)” philosophy of the ISO 9001 quality management system results in a continuous improvement process.

Methods

1015 proximal femoral fractures were prospectively included into a hip fracture database over a 5-year period, after a restructuring process with implementation of clinical pathways and standard operation procedures. A close and structured ortho-geriatric co-management (certified ortho-geriatric center) was the basis for treatment. ISO 9001 certification was granted for the first time in 2012. Procedural and patient outcome parameters were analyzed by year and evaluated statistically using SPSS 25.0.

Results

In both categories (procedural and outcome) significant changes could be detected during the 5-year period, e.g., significant reduction of time to surgery for the first 2 years, improvement in discharge management, and reduction of surgical complications. However, no significant changes could be demonstrated for mortality or internal complications such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections, or postoperative delirium. However, the incidence of the latter was already on a very low level at the onset of the quality improvement process.

Conclusion

We could show a relevant and continuous improvement of several quality indicators during a 5-year period after implementation of a quality management system based on the PDCA philosophy for the treatment of proximal femoral fractures in elderly patients. However, other parameters (internal complications, cost-effectiveness, etc.) need our close attention in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Hip fractures are among the most challenging injuries in elderly people. Even if epidemiological data vary between countries, it is estimated that hip fractures will affect around 18% of all women and 6% of all men globally. More than 400,000 women and 100,000 men will be affected within the European Union every year [1]. Although the age-standardized incidence has been gradually decreasing in many countries, the overall number of hip fractures is expected to increase from 1.26 million in 1990 to 4.5 million by the year 2050 [2].

A high excess mortality is well described after hip fracture [3], which persists even 10 years after the fracture has occurred [4]. Moreover, patients with a proximal femur fracture experience a clinically important decline in functional status with considerable loss in quality of life [5]. Within 1 year after proximal femoral fracture (PFF), more than 20% of the patients will have to be institutionalized because of the fracture [6].

Organizing and standardizing the care process for these patients, with a focus on quality and efficiency, is one of the priorities for the next decade for health-care providers, health-care managers, and policymakers [7, 8].

One option to (re)organize the care process is the implementation of a quality management system (e.g., ISO 9001, European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM), Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award) [9,10,11].

In a recent study, we showed that the implementation of clinical pathways as part of a quality management system leads to a relevant quality improvement [3]. In a prospective clinical trial using a pre-during-post design, we demonstrated that quality indicators improved significantly: processes improved [e.g., time to surgery, number of patients included in an early geriatric rehabilitation program (EGRP)], general complications decreased, and less patients had to be institutionalized. At the same time, the recorded number of postoperative delirium and acquired decubiti increased due to a better awareness and improved documentation [12].

These efforts were expanded to meet the criteria of the ISO 9001:2008 system. Table 1 summarizes the key elements leading to the certification of the geriatric trauma center in 2012. The ISO 9000 family of quality management standards is designed to help organizations ensure that they meet the needs of customers and other stakeholders while meeting statutory and regulatory requirements related to a product or service [13].

One core element is the PDCA (plan–do–check–act) or Deming cycle, an iterative four-step management method used for the control and continuous improvement of processes (CIP), service and care delivery [14]. These efforts can seek “incremental” improvement over time or “breakthrough” improvement all at once. Delivery (customer valued) processes are constantly evaluated and improved in the light of their efficiency, effectiveness and flexibility.

The quality management system ISO 9001 has been shown to improve care delivery in several studies [1, 2]. However, no clinical trials have been published to analyze the effect of this complex and costly intervention in hip fracture management. Therefore, the overall goal of this study was to evaluate the outcome of the implementation of a quality management system, namely the ISO 9001, with particular focus on the continuous improvement process in hip fracture management.

Patients and methods

The present study was designed as a single-center cohort study and conducted in a charitable 1031 bed, academic teaching hospital with approximately 44,000 admissions annually and roughly 250 proximal femoral fractures.

With the decision to implement a quality management system for the treatment of elderly patients with proximal femoral fractures, it was decided to evaluate its effects prospectively.

Routine data were collected along the clinical pathways and recorded in a clinical database.

Approval by the institutional review board (IRB) was obtained prior to the study and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Inclusion–exclusion criteria

All patients consecutively admitted for PFF were considered for inclusion based on the following criteria: (1) closed fracture of the proximal femur: femoral neck fracture, per-and intertrochanteric fractures (according to the AO-classification 31 A1–3 and B); (2) age above 80 years, or age above 65 years with relevant co-morbiditiesFootnote 1 (3) eligible for surgical intervention.

Exclusion criteria were: pathological fracture (except osteoporotic), peri-prosthetic fracture, isolated fractures of the greater trochanter and multiply injured patients.

Intervention

Implementation of a quality management system and certification according to the ISO 9001 system. Key elements of this complex intervention are summarized in Table 1.

One core element of the quality management system is the PDCA cycle:

P (Plan): clinical pathways were developed using a multidisciplinary approach during several workshops (quality circles) and consented by a steering committee.

The following sub-processes were defined and standardized: (1) emergency treatment, (2) surgical treatment, (3) intensive care, (4) postoperative care, (5) early geriatric rehabilitation [15].Footnote 2

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) were established for: activating care, bridging of anticoagulants, decubitus, delirium, nutrition management, osteoporosis, pain management.

D (Do): care pathways and SOPs were implemented during the first year (2012) and ISO 9001:2008 certification was granted.

C (Check): clinical care pathways were controlled using checklists, and quality indicators were collected (Table 2) and assessed by the steering committee.

A (Act): based on the results of the quality indicators/outcome parameters, quality circles were engaged with improving the care pathways, structural and staff issues.

Major interventions during the 5-year period included: implementation of an interdisciplinary ward, increase of geriatric nursing competence in the care team, and increase in the capacity for early geriatric rehabilitation (physical therapy, occupational therapy). Expansion of cooperation (endocrinology/osteology; nutrition specialists, dentist).

Patients were included after radiological confirmation of the diagnosis of a proximal femoral fracture. Data were collected during acute hospital treatment (17 ± 8 days), and a follow-up of 30 ± 9 days (mean ± SD). Quality indicators (Table 2) were recorded using checklists and documented in a hip fracture database.

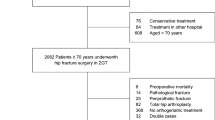

A total of 1015 patients were included in the study during the 5-year period. Analysis was performed by year. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the patients. Demographic data are displayed in Table 3.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0. The different groups (years) were tested for homogeneity with respect to age, age distribution and sex using Pearson’s Chi-squared test and Kruskal–Wallis test. Missing values were replaced using the SPSS algorithm.

Parametric and nonparametric statistical tests were used to analyze the test variables. First, they were tested for homoscedasticity using Levene’s statistics. If homoscedasticity could be assumed throughout the groups, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for significant differences between the groups. In case of heteroscedasticity, a robust test (Welch test) was used. Where necessary, Bonferroni or Games–Howell post hoc tests were used. Statistical significance was assumed with p < 0.05.

Results

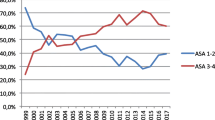

The mean age of the patients was 83.3 (± 7.7) years. As expected, more female (73%) than male (27%) patients were included. The five cohorts (2012–2016) were homogeneous in terms of age, age distribution (Kruskal–Wallis test, p = 0.462) and sex (Pearson’s Chi square test p = 0.23).

Outcome parameters were divided into procedural parameters and patient outcome parameters.

In both categories, significant changes could be detected during the 5-year period.

Concerning the procedural parameters, a significant decrease of the “time to surgery” could be achieved for the first 2 years, followed by a sudden significant increase in the year 2016 (Table 3). In this respect, it is important to mention that OR capacity was reduced by 10% in 2016 due to lack of staff. While time to the “first contact with a geriatrician” decreased continuously between 2012 and 2016 (Welch test, p < 0.001), time to the “first contact with a physiotherapist” was relatively stable (ANOVA, p = 0.186). However, it was possible to mobilize significantly more patients during the first 24 h (Welch test, p = 0.026). The number of patients included in an “early geriatric rehabilitation program (EGRP)” increased significantly from 52 to 75% (Welch test, p < 0.001). An increasing number of patients could be discharged home (Welch test, p < 0.001) or to a geriatric rehabilitation program (ANOVA, p = 0.014) over the 5-year period. No significant changes in length of stay were detected (p = 0.228). The results are summarized in Table 3.

Patient outcome parameters showed a significant decrease of implant failure during the 5-year period (Welch test, p < 0.001) and a trend toward a lower revisions rate (mean 1.9%), ANOVA, p = 0.104.

Interestingly, a continuous increase of detected postoperative delirium was documented (Welch test, p < 0.001).

No significant differences were detected for mortality (during the observation period of 30 days), local complications (infection) and internal complications (e.g., renal failure, pneumonia or decubitus acquired during therapy).

Mean Barthel’s Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Index increased significantly during the first 14 days postoperatively (Fig. 2), However, no significant change of the levels achieved was detected over the 5-year period.

Table 3 shows the results of the outcome parameters, including statistical analysis.

Discussion

With implementation of a quality management system in 2012, quality indicators (Table 2) were recorded between 2012 and 2016. The data presented show that procedural parameters and outcome parameters improved over the 5-year period in small, but significant steps according to the ISO philosophy “continuous improvement process”. This was achieved by implementing the PDCA cycle [16].

“Time to surgery”, an important quality indicator [17, 18], improved during the first 2 years, but deteriorated during the following 3 years. A likely explanation might be the reduction of OR capacity in 2015/2016, and the overall increasing number of anticoagulated patients [19]. Especially the increasing prevalence of new oral anticoagulants (NOACs), where no clear recommendation on waiting time before surgery is available, is an important issue. Time to surgery has been shown to be an important predictor for 30 days postoperative mortality in several studies [17, 18]. Although the exact cutoff is still unknown, a recent large population-based study in Canada (retrospective cohort study with 72 hospitals and 42,230 patients) suggested that a wait time of 24 h may represent a threshold defining higher risk [18]. Another study showed that coordinated, region-wide efforts to improve timeliness of hip fracture surgery successfully reduced time to surgery and appeared to reduce the length of stay and adjusted mortality in hospital and at 1 year [20]. A reduction of time to surgery with a coordinated quality management system was described by Saez-Lopez et al. for the Spanish system [21, 22], Lau et al. in Hong-Kong [23], and Kalmet et al. for the Dutch system [24]. This negative development during the latter 3 years was addressed by several quality circles with OR-management to prioritize PFF treatment. Together with the Department of Anesthesiology, the SOP for the management of anticoagulated patients was revised. This led again to a significant decrease in time to surgery in 2017 (− 2 h, t test; p < 0.001Footnote 3).

In our cohort, “length of stay” was constant over the 5-year period (ANOVA, p = 228). This is in contrast to the results reported by Burgers et al. [25], Fliweert et al. [26] and Kalmet et al. (Dutch system), or Koval et al. [27, 28] (US system), as well as Soong et al. [29] (Canadian System), who documented a significant decrease of “length of stay” with the implementation of clinical pathways for hip fracture management. However, reduction of length of stay was not our primary intention. Moreover, these studies are difficult to compare, since the national health systems differ substantially.

Our result show that an increasing number of patients were included in an “early geriatric rehabilitation program” (52% in 2012 up to 75% in 2016, Welch test, p < 0.001), providing more access to physical and occupational therapy.

Other parameters that improved similarly were: start of EGRP (Welch test, p < 0.001), mobilization within 24 h of surgery (Welch test, p = 0.026), and time to geriatric consultation (< 0.001).

However, these quality indicators did not improve continuously, but showed “stepwise” improvement from 2012 to 2013 and again in 2016 (Table 3). Increase in the number of patients included in the EGRP, a personnel-intensive intervention, was only possible with an increase in the staff resources. This has to be taken into account, when considering the overall costs. In our setting, the following costs were incurred for the expansion of the EGRP in 2016 (mainly personnel costs): Par-time positions for: geriatric trainee, physical and occupational therapist, and case manager; comprising a total of approximately 110.000 €. These costs are refinanced by an additional receipt of approximately 4.600 € per case. Currently, the ProFinD2 study evaluates the cost-effectiveness of this program [30]. To date, this program is relatively inflexible and reimbursement is a major concern. Several criteria have to be fulfilled and a fixed number of treatments are required for reimbursement purposes (at least 20 sessions of (physical) therapy within 14 days). One consequence is an extended length of stay in comparison to hospitals/units not providing this program. In our own cohort, changes in length of stay increased from 16 to 18 days (p = 0.228) during the 5-year period.

Despite the above-mentioned improvements, postoperative 30-day-mortality did not change significantly. It remained stable at a low level (5.4%, Welch test, p = 0.632). This is in contrast to other works. Koval et al. [27, 28] (US system) and Forni et al. [31] (Italian system) showed significant changes in postoperative mortality with implementation of clinical pathways for hip fracture management. On the other hand, our result corresponds to the findings of Beaupre et al. [32] (Canadian system) and Kalmet et al. (Dutch system) [24]. They found a reduction of postoperative morbidity, but not in-hospital mortality.

During the observation period, we could not accomplish a decrease in the incidence of acquired pneumonia, urinary tract infection or kidney failure, despite more promising results in the early phase of our study (2011/2012) [12].

The increasing number of postoperatively detected delirium persisted throughout the observation period (Table 3). This was reported earlier by others in the early phase after implementation of the clinical pathways. Generally, this increase is followed by a decrease of postoperative delirium with the interventions later [33, 34]. This reduction was not jet detected in our cohort. More efforts (e.g., teaching, sufficiently well-trained staff) are necessary to improve the outcome in this respect. However, the number of delirium recorded is not only confounded by an increase in detection, but also by a possible decrease in incidence with the multidisciplinary approach. Overall, the rate of hip fracture patients that suffer a delirium is relatively low and comparable to those reported in other intervention studies [35, 36].

Other parameters improved significantly, e.g., failure of fixation (p < 0.001) or fixations with full weight-bearing postoperatively (p < 0.001). Possible explanations are: surgical SOPs, teaching efforts, morbidity and mortality conferences, etc.

Among the limitations of this study is the lack of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), e.g., quality of life. Griffin et al. criticized the lack of patient-reported outcomes in the British national database and conducted a cohort study showing that quality of life does not improve significantly during recovery from hip fracture (120 days) in patients over 80 years of age [5]. Since 2017, we have been reporting our data to a national geriatric hip fracture database. This includes patient-related outcome; however, results are not yet available.

The established quality management system is a learning system. We showed the improvement of several parameters over a 5-year period. However, others have not improved yet. According to the PDCA philosophy, we will have to work on interventions decreasing postoperative pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and prevention and treatment of postoperative delirium, among others. Moreover, we have to enhance the knowledge of the medical and nursing staff regarding the geriatric trauma patient (additional geriatric qualification is required), evaluate new concepts of nursing (e.g., primary care nursing) [37], and further optimize room concepts for disabled elderly patients.

Further studies must show whether the implementation of multifactorial interventions has an impact on mid- or long-term outcome in terms of: mortality, morbidity, mobility and independence. Due to limited funding, we had to restrict our follow-up to 30 days. With the implementation of a national geriatric hip fracture database, follow-up will be extended to 120 days.

Last but not least, the cost-effectiveness of the obviously time and resource-consuming implementation of quality management systems for hip fracture management has to be analyzed.

Conclusion

We showed significant and relevant improvements in hip fracture care in elderly patients with the implementation of a quality management system based on the PDCA philosophy (continuous improvement process). The basis for a successful treatment is a close ortho-geriatric co-management. However, many questions remain open. More long-term observational studies are needed to judge the effect of our current efforts toward a better management of this patient collective.

Notes

Diabetes mellitus with end-organ damage, liver disease, moderate to severe, malignancy, moderate to severe chronic kidney disease, chronic heart failure, myocardial infarction, COPD, dementia, hemiplegia. Corresponding to a Charleston Comorbidity Index of 4 and above and an estimated 10-year survival of less than 50%, the geriatrician responsible decided upon inclusion and exclusion.

Early geriatric rehabilitation program: geriatric and social assessment, weekly teem meeting, activating care of specially trained nursing staff, 20 units of physical and occupational therapy during a 14-day period.

Data not presented.

References

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Jonsson B, De Laet C, Dawson A (2000) Risk of hip fracture according to the World Health Organization criteria for osteopenia and osteoporosis. Bone 27(5):585–590

Veronese N, Maggi S (2018) Epidemiology and social costs of hip fracture. Injury. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2018.04.015

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, De Laet C, Jonsson B, Oglesby AK (2003) The components of excess mortality after hip fracture. Bone 32(5):468–473

Haentjens P, Magaziner J, Colon-Emeric CS, Vanderschueren D, Milisen K, Velkeniers B, Boonen S (2010) Meta-analysis: excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Med 152(6):380–390. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-152-6-201003160-00008

Griffin XL, Parsons N, Achten J, Fernandez M, Costa ML (2015) Recovery of health-related quality of life in a United Kingdom hip fracture population. The Warwick Hip Trauma Evaluation—a prospective cohort study. Bone Joint J 97-B(3):372–382. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.97B3.35738

Cumming RG, Klineberg R, Katelaris A (1996) Cohort study of risk of institutionalisation after hip fracture. Aust N Z J Public Health 20(6):579–582

Leigheb F, Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W, Lodewijckx C, Deneckere S, Boonen S, Boto PA, Mendes RV, Panella M (2012) The effect of care pathways for hip fractures: a systematic review. Calcif Tissue Int 91(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-012-9589-2

Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W, Peers J, Lodewijckx C, Deneckere S, Leigheb F, Boonen S, Sermon A, Boto P, Mendes RV, Panella M, EQCP Study Group (2012) The impact of care pathways for patients with proximal femur fracture: rationale and design of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res 12:124. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-124

Yousefinezhadi T, Mohamadi E, Safari Palangi H, Akbari Sari A (2015) The effect of ISO 9001 and the EFQM model on improving hospital performance: a systematic review. Iran Red Crescent Med J 17(12):e23010. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.23010

Moeller J, Breinlinger-O’Reilly J, Elser J (2000) Quality management in German health care—the EFQM Excellence Model. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv 13(6–7):254–258

Duarte NT, Goodson JR, Arnold EW (2013) Performance management excellence among the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award Winners in Health Care. Health Care Manag (Frederick) 32(4):346–358. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCM.0b013e3182a9d704

Tittel S, Burkhardt J, Roll C, Kinner B (2018) Clinical pathways for geriatric patients with proximal femoral fracture improve quality of care delivery and outcome. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res (submitted)

Poksinska B, Dahlgaard JJ, Antoni M (2002) The state of ISO 9000 certification: a study of Swedish organizations. TQM Mag 14(5):297. https://doi.org/10.1108/09544780210439734

Tague NR (2005) “Plan–Do–Study–Act cycle”. The quality toolbox, 2nd edn. ASQ Quality Press, Milwaukee

Logters T, Hakimi M, Linhart W, Kaiser T, Briem D, Rueger J, Windolf J (2008) Early interdisciplinary geriatric rehabilitation after hip fracture: effective concept or just transfer of costs?. Unfallchirurg 111(9):719–726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00113-008-1469-x

Vogel P, Vassilev G, Kruse B, Cankaya Y (2011) Morbidity and mortality conference as part of PDCA cycle to decrease anastomotic failure in colorectal surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg 396(7):1009–1015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-011-0820-9

Casaletto JA, Gatt R (2004) Post-operative mortality related to waiting time for hip fracture surgery. Injury 35(2):114–120

Pincus D, Ravi B, Wasserstein D, Huang A, Paterson JM, Nathens AB, Kreder HJ, Jenkinson RJ, Wodchis WP (2017) Association between wait time and 30-day mortality in adults undergoing hip fracture surgery. JAMA 318(20):1994–2003. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.17606

Gulati V, Newman S, Porter KJ, Franco LCS, Wainwright T, Ugoigwe C, Middleton R (2018) Implications of anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy in patients presenting with hip fractures: a current concepts review. Hip Int 28(3):227–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1120700018759300

Bohm E, Loucks L, Wittmeier K, Lix LM, Oppenheimer L (2015) Reduced time to surgery improves mortality and length of stay following hip fracture: results from an intervention study in a Canadian health authority. Can J Surg 58(4):257–263

Saez Lopez P, Sanchez Hernandez N, Paniagua Tejo S, Valverde Garcia JA, Montero Diaz M, Alonso Garcia N, Freites Esteve A (2015) Clinical pathway for hip fracture patients. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 50(4):161–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regg.2014.11.003

Sanchez-Hernandez N, Saez-Lopez P, Paniagua-Tejo S, Valverde-Garcia JA (2016) Results following the implementation of a clinical pathway in the process of care to elderly patients with osteoporotic hip fracture in a second level hospital. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol 60(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recot.2015.08.001

Lau TW, Leung F, Siu D, Wong G, Luk KD (2010) Geriatric hip fracture clinical pathway: the Hong Kong experience. Osteoporos Int 21(Suppl 4):S627–S636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1387-y

Kalmet PH, Koc BB, Hemmes B, Ten Broeke RH, Dekkers G, Hustinx P, Schotanus MG, Tilman P, Janzing HM, Verkeyn JM, Brink PR, Poeze M (2016) Effectiveness of a multidisciplinary clinical pathway for elderly patients with hip fracture: a multicenter comparative cohort study. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 7(2):81–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/2151458516645633

Burgers PT, Van Lieshout EM, Verhelst J, Dawson I, de Rijcke PA (2014) Implementing a clinical pathway for hip fractures; effects on hospital length of stay and complication rates in five hundred and twenty six patients. Int Orthop 38(5):1045–1050. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-013-2218-5

Flikweert ER, Izaks GJ, Knobben BA, Stevens M, Wendt K (2014) The development of a comprehensive multidisciplinary care pathway for patients with a hip fracture: design and results of a clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 15:188. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-188

Koval KJ, Chen AL, Aharonoff GB, Egol KA, Zuckerman JD (2004) Clinical pathway for hip fractures in the elderly: the Hospital for Joint Diseases experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res (425):72–81

Koval KJ, Cooley MR (2005) Clinical pathway after hip fracture. Disabil Rehabil 27(18–19):1053–1060. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280500056618

Soong C, Cram P, Chezar K, Tajammal F, Exconde K, Matelski J, Sinha SK, Abrams HB, Fan-Lun C, Fabbruzzo-Cota C, Backstein D, Bell CM (2016) Impact of an integrated hip fracture inpatient program on length of stay and costs. J Orthop Trauma 30(12):647–652. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000000691

Becker C (2017) https://www.gesundheitsforschung-bmbf.de/de/PROFinD-2-Osteoporotische-Frakturen-Praevention-und-Rehabilitation.php

Forni S, Pieralli F, Sergi A, Lorini C, Bonaccorsi G, Vannucci A (2016) Mortality after hip fracture in the elderly: the role of a multidisciplinary approach and time to surgery in a retrospective observational study on 23,973 patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 66:13–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2016.04.014

Beaupre LA, Cinats JG, Senthilselvan A, Lier D, Jones CA, Scharfenberger A, Johnston DW, Saunders LD (2006) Reduced morbidity for elderly patients with a hip fracture after implementation of a perioperative evidence-based clinical pathway. Qual Saf Health Care 15(5):375–379. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2005.017095

Frolich F, Chmielnicki M, Prokop A (2015) Geriatric complex treatment of proximal femoral fractures? Who profits the most?. Unfallchirurg 118(10):858–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00113-013-2554-3

Prokop A, Reinauer KM, Chmielnicki M (2015) Is there sense in having a certified centre for geriatric trauma surgery?. Z Orthop Unfall 153(3):306–311. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1545710

Marcantonio AJ, Pace M, Brabeck D, Nault KM, Trzaskos A, Anderson R (2017) Team approach: management of postoperative delirium in the elderly patient with femoral-neck fracture. JBJS Rev 5(10):e8. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.RVW.17.00026

Todd KS, Barry J, Hoppough S, McConnell E (2015) Delirium detection and improved delirium management in older patients hospitalized for hip fracture. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs 19(4):214–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijotn.2015.03.005

Jost SG, Bonnell M, Chacko SJ, Parkinson DL (2010) Integrated primary nursing: a care delivery model for the 21st-century knowledge worker. Nurs Admin Q 34(3):208–216. https://doi.org/10.1097/NAQ.0b013e3181e7032c

Funding

There is no funding source.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Approval by the internal review board (IRB) was obtained.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Roll, C., Tittel, S., Schäfer, M. et al. Continuous improvement process: ortho-geriatric co-management of proximal femoral fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 139, 347–354 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-018-3086-7

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-018-3086-7