Abstract

Introduction

Patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) have a heightened risk of sustaining hip fractures due to disturbed balance and gait insecurity. This study aims to determine the impact of PD on the perioperative course and medium-term functional outcome of patients with hip fractures.

Materials and methods

A total of 402 hip fracture patients, aged ≥60 years, were prospectively enrolled. On admission, the American Society of Anesthesiologists score, Mini-Mental Status Examination, and Barthel Index (BI), among other scales, were documented. The Hoehn and Yahr scale was used to assess the severity of PD. The functional outcome was assessed by performance on the BI, Tinetti test (TT), and Timed Up and Go test (TUG) at discharge and at the 6-month follow-up. Additionally, the length of hospitalization, perioperative complications, and discharge management were documented. A multivariate regression analysis was performed to control for influencing factors.

Results

A total of 19 patients (4.7 %) had a concomitant diagnosis of PD. The functional outcome (BI, TT, and TUG) was comparable between groups (all p > 0.05). Grade II (52.6 vs. 26.1 %; OR = 4.304, p = 0.008) and IV complications (15.8 vs. 4.4 %; OR = 7.785, p = 0.012) occurred significantly more often among PD patients. While the diagnosis of PD was associated with a significantly longer mean length of hospital stay (β = 0.119, p = 0.024), the transfer from acute hospital care showed no significant difference (p = 0.246). Patients with an additional diagnosis of PD had inferior results in BI at the 6-month follow-up (p = 0.038).

Conclusion

PD on hospital admission is not an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality or an inferior functional outcome at hospital discharge. However, patients with PD are at risk for specific complications and longer hospitalization at the time of transfer from acute care so as for reduced abilities in activities of daily living in the medium term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Like no other osteoporotic fracture, a hip fracture affects the subsequent life of a patient. This is indicated by a high one-year mortality rate of approximately 25 % [1, 2], and approximately one-third of patients that lose their self-dependence within the same period [3, 4]. Thus, these mainly geriatric injuries remain a multidisciplinary challenge [5]. Circumstances that lead to hip fractures mostly involve simple falls, which are often associated with malnutrition, the loss of sensorial skills, and insecurity in motor coordination and walking [6].

An especially vulnerable group of patients are geriatric patients with a concomitant diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Previous studies have shown that patients with PD have a 2.6- to 4.0-fold increased risk of sustaining fractures of the proximal femur compared to sex- and age-matched members of the general population [7–9]. Other studies suggest that in PD patients, various parameters negatively impact bone mineral density, even in early stages of the disease. Such parameters include the following: (1) PD patients are less active than are healthy controls due to decreased muscle strength and low body weight, all of which contribute to bone mass loss; (2) vitamin D deficiency; and (3) hyperhomocysteinemia, an independent risk factor for osteoporosis due to levodopa therapy [10].

The prevalence and incidence rates of PD in Europeans in older age groups (>60 years) are 1280–1500/100,000 and 346/100,000, respectively [11]. PD is characterized by a loss of dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway, leading to symptoms that include resting tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability, resulting in disturbed balance and gait insecurity. Currently, drugs are the main treatment option used to manage the symptoms of PD and are mainly aimed at increasing the level of dopamine in the brain tissue. While this therapy offers an effective PD treatment, many anti-PD drugs must be taken within a tight schedule to achieve optimal symptom control. In this context, surgical admission presents a particular risk. In addition to undergoing surgical procedures and anesthesia, patients are usually treated by medical and nursing staff who are relatively inexperienced in PD management. This can lead to a discontinuity in the application of PD drugs and disturb the otherwise constant drug levels, thus possibly impairing the early functional outcome of patients with PD.

The results from a prospective fracture database confirm this assumption, as they revealed that patients with PD took significantly longer to be discharged from the hospital and were less mobile compared to patients without PD [12]. However, retrospective analysis and the results of prospective studies conducted at university teaching hospitals on patients with PD who underwent hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fractures concluded that there was no influence of PD on the outcome following a hip fracture [13, 14]. These conflicting results contribute to the ongoing discussion of whether PD influences the perioperative course and functional outcome of hip fracture patients [15].

Therefore, the present prospective study was undertaken to determine the impact of PD on the perioperative course and medium-term functional outcome of patients with hip fractures.

Patients and methods

A total of 402 patients (aged ≥60 years) who had sustained a hip fracture were included in this prospective, single-center, observational study. The criteria for exclusion included multiple trauma (ISS ≥16) and malignancy-associated fracture. All patients were surgically treated with either internal fixation or hip arthroplasty. The recruitment period was from April 1, 2009 to September 30, 2011. Approval by the local Ethics Committee was obtained for this study. Each patient or legal representative of the patient gave written informed consent.

On admission to our hospital, the patient’s age, gender, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score [16], pre-fracture Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [17], Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) [18], and fracture type were documented. The patients were asked to provide information on their functional and residential status before the injury. The functional status was measured by the pre-fracture Barthel Index (BI) [19]. The residential status was categorized as living alone or with family members or residing at a nursing home.

Assessment of PD and staging

The diagnosis of PD was based on the patient’s medical history on admission combined with the intake of anti-PD medication. Following a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP), patients with a diagnosis of PD were seen by a neurologist during their stay in the hospital for further investigation and therapy optimization, if necessary. The Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) scale was used by the neurological expert to assess the severity of PD [20]. The rating refers to the “on phase” of PD. The H&Y scale is a widely used clinical rating scale. It defines broad categories of motor function and distinguishes among five severity stages (H&Y I–V):

Stage I: Unilateral involvement only, usually with minimal or no functional impairment.

Stage II: Bilateral or midline involvement, without impairment of balance.

Stage III: First sign of impaired righting reflexes. This is evident by unsteadiness as the patient turns or is demonstrated when he is pushed from standing equilibrium with the feet together and eyes closed. Functionally the patient is somewhat restricted in his activities but may have some work potential depending upon the type of employment. Patients are physically capable of leading independent lives, and their disability is mild to moderate.

Stage IV: Fully developed, severely disabling disease; the patient is still able to walk and stand unassisted but is markedly incapacitated.

Stage V: Confinement to bed or wheelchair unless aided [20].

Outcome parameters

The patients’ functional results were monitored using the BI, Tinetti test (TT) (balance and gait) [21], and Timed Up and Go test (TUG) [22] at discharge. Furthermore, the patient’s overall length of hospital stay and destination after hospital discharge were documented. The in-hospital mortality and rate of perioperative complications (according to the Clavien–Dindo classification) were both documented to account for their differing clinical relevance [23]. Due to a lack of relevance, complications classified as grade I according to Clavien et al. were not reported [23]. Functional outcome and mortality rate were also assessed at a 6-month follow-up examination.

Data entry and statistics

Data were collected in a Filemaker database® (FileMaker Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Double entry with a plausibility check was performed to ensure data quality. IBM SPSS statistics 22 (Statistical Package for the Social Science, IBM Cooperation, Armonk, N.Y., USA) was used for statistical analysis.

The normality of distribution was evaluated by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. For the metric variables, such as age, ASA score, CCI, BI, length of hospital stay, and TUG, an unpaired Student’s t test was used to compare patients with PD to patients without PD. For the categorical variables, such as gender distribution, type of surgery, mortality rate and the occurrence of complications between the patient groups, differences were evaluated using Fisher’s exact test. To determine the distributions of the various fracture types, a Chi-square test was conducted. For all tests, significance was assumed at p < 0.05. To further assess the influence of PD, a multivariate linear regression analysis with backward selection was performed for variables that were significant in the bivariate analysis (grade II and IV complications, the length of hospital stay, BI and TT gait). This analysis included the following co-variables that are known to influence patient outcome after hip fracture: pre-fracture BI, pre-fracture CCI, MMSE score, pre-fracture residence in a nursing home, ASA score, fracture type, time between admission and surgery, type of surgical treatment (internal fixation vs. prosthesis), gender and age.

Results

During the recruitment period, 402 patients were enrolled in this study. Among the included patients, 19 patients (4.7 %) also had a diagnosis of PD on admission (Table 1). While approximately one quarter of the PD patients presented with only mild symptoms of PD (H&Y I and II; 26.3 %), the majority of PD patients presented with moderate to severe symptoms (H&Y III and IV; 57.9 %). Additionally, 15.8 % of the PD patients had already reached an advanced stage and were classified as H&Y stage V. Compared with female patients, significantly more male patients were affected by PD (3.4 vs. 8.3 %; p = 0.042). In addition, patients diagnosed with PD had significantly higher ASA scores on admission (3.2 ± 0.6 vs. 2.9 ± 0.6, p = 0.009). No significant differences were found in the pre-fracture BI (p = 0.052), pre-fracture CCI (p = 0.573), cognitive ability according to the MMSE (p = 0.078), age on admission to hospital (p = 0.421) and pre-fracture residential status (p = 0.577).

In terms of the perioperative clinical course, no differences were observed based on the period of time from hospital admission to surgery (p = 0.883) or the distribution of surgical treatment (prosthesis vs. internal fixation, p = 0.566). Regarding the functional outcome, as indicated by the results at discharge, of the BI (p = 0.103), TT balance (p = 0.062), TT gait (p = 0.147), and TUG (p = 0.978), no significant differences were observed between the groups (Table 2). The mean length of hospital stay for patients with PD was 17 ± 10 days, which was significantly longer than that of patients without PD (14 ± 6 days, p = 0.034) (Table 2).

In terms of the perioperative complication rate according to the Clavien–Dindo classification, a mixed picture was revealed. There were significant differences in the occurrence of grade II (52.6 vs. 26.1 %; p = 0.011) and grade IV complications (15.8 vs. 4.4 %; p = 0.026), with urinary tract infections accounting for 90 % of all grade II complications in PD patients (p = 0.025). No statistically significant differences were detected among grade III (p = 0.871) and grade V complications (p = 0.240) (Fig. 1). The in-hospital mortality rate (grade V complication) for all patients was 6.2 %, and the overall length of hospital stay was 14 ± 6 days (Table 2). In the multivariate analysis of variables recorded at discharge, significant differences were observed in the grade II complications (R 2 = 0.059, OR = 4.304, p = 0.008), grade IV complications (R 2 = 0.128, OR = 7.785, p = 0.012) and mean length of hospital stay (R 2 = 0.151, β = 0.119, p = 0.024) between the two groups (Table 3).

The complication grades correspond to those described by Clavien et al. and are adapted to our study population, except grade I due to a lack of relevance [23]. The complications are shown as the percentage of all patients (multiple responses possible). *Patient requiring pharmacological treatment (urinary tract infection, pneumonia, hypohydration, atrial fibrillation, pulmonary edema, electrolyte imbalance, infection of central venous catheter, infectious diarrhea, and respiratory obstruction). **Patient requiring surgical treatment (hematoma, pleural effusion, seroma, deep wound infection, cholecystitis, failure of osteosynthesis, ileus, diverticular hemorrhage, luxation of prosthesis, periprosthetic fracture, and postoperative hemorrhage). ***Patient suffering from life-threatening complications (myocardial infarction, acute renal failure, ischemic stroke, respiratory failure, acute heart failure, epileptic seizure, and perforated sigma diverticulitis). ****Patient death

With respect to transfer from acute hospital care, no significant differences were observed. Patients both with and without a diagnosis of PD were discharged to rehabilitation facilities at approximately the same rate (63.3 vs. 66.2 %; p = 0.246). While also the rate of transferral home was approximately equal in the two groups, all patients with PD coming from nursing homes where returned to nursing facilities without further rehabilitation. Overall, patients with PD had an insignificantly higher discharge rate to nursing homes (26.2 vs. 13.1 %; p = 0.246) (Table 4).

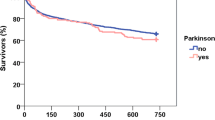

Whereas TT gait (p = 0.160) and TUG (p = 104) where comparable between both groups, functional outcome was reduced according to BI (p = 0.001) and TT balance (p = 0.002) at the 6-month follow-up (Table 2). According to a multivariate analysis, adjusted for known influencing factors, these differences could only be seen for the BI (R 2 = 0.596, β = −0.094, p = 0.038) (Table 3). Concerning the mortality rate half year after the surgical treatment, no differences could be seen between patients with (10.5 %) and without (20.6 %) the diagnosis of PD (p = 0.388).

Discussion

Aim of the current study was to analyze the impact of PD on the clinical and medium-term course of geriatric patients with hip fractures. The principle findings of the present study revealed no differences in functional outcome between patients with and without PD at the time of discharge. Nevertheless, patients with a diagnosis of PD exhibited higher rates of complications and longer hospital stays.

Almost three-quarters of the included PD patients presented with H&Y stage III–V. Nevertheless, these advanced H&Y stages did not affect the functional baseline abilities in general, as indicated by comparable values for pre-fracture BI and residential status. Additionally, in terms of the postoperative functional outcome at discharge, the results for patients were comparable to those for non-affected patients, as indicated by insignificantly lower values for the BI, TT, and TUG. These findings are in agreement with a report by Yuasa et al. [13] on the postoperative functional outcome in hip fracture patients with PD. Although functional assessments (BI, CCI, TT and TUG) were performed neither on admission nor at discharge in that study, the authors conclude that the postoperative walking ability, as the only measure of functional outcome referenced, was comparable to that of the controls. In contrast to the results of the present study and those of Yuasa et al., Walker et al. found that patients with PD were significantly more likely to be confined to a bed or wheelchair at the time of discharge from acute hospital care [12]. These conflicting results can be explained by comparing the length of hospital stay. While Walker et al. found no difference in the length of stay in hospital between the two groups, patients with PD were discharged significantly later in the present study [12]. Therefore, it can be presumed that patients with and without PD can achieve comparable postoperative functional results; however, patients with PD need more time for mobilization under physiotherapeutic therapy and postoperative medical treatment. Additionally our observation, of inferior results in BI at the 6-month follow-up, might be related to a lack of outpatient physiotherapeutic therapy in the time following the hospital stay, leading to a reduced performance in activities of daily living at this time.

Grade II complications occurred significantly more often among patients with PD. A closer examination of this grade of complication revealed that urinary tract infections accounted for 90 % of all outcomes classified as grade II complications. Even though urinary tract infections are generally common among geriatric hip fracture patients [24], these results confirm the findings of Weber et al., which report elevated rates of urinary tract infection following total hip arthroplasty in PD patients [25]. These increased rates of urinary tract infection following hip fracture might be explained by PD-related bladder dysfunction due to postmicturitional residual urine [26]. Delayed mobilization of these patients also has additional negative effects on independent urine control and toilet use, potentially prolonging the use of urinary catheters. Therefore, close meshed urinalysis might be useful for inpatient treatment of hip fracture patients with PD. Furthermore, grade IV complications were found to be significantly increased among patients with PD (one renal failure and two myocardial infarctions). These findings coincide with those of cross-sectional observational studies of comorbidities in PD patients conducted in the United States [27]. Therein, PD patients were shown to be at a significantly increased risk of suffering from ischemic cardiac disease compared to controls. In the present study population, this predisposition toward life-threatening complications (grade IV) was preoperatively assumed among PD patients, as indicated by significantly higher estimates for the ASA score. PD patients suffering from hip fractures must, therefore, be regarded as a particularly vulnerable patient population. Such elevated rates of severe complications might have also contributed to prolonged hospital stays among patients with diagnosis of PD (17 ± 10 vs. 14 ± 6 days). Due to the fact that the German DRG system provides a maximum length of stay for the diagnosis of “hip fracture” which is between 10, 9 und 19, 6 days, only severe complications (like complications grade IV) are able to lead to an outlier in-hospital length of stay.

The increased fragility of patients with PD is also mirrored in their discharge management. In the present study population, all patients with a diagnosis of PD coming from nursing homes where sent back to nursing facilities without giving them a further opportunity for recovery at a rehabilitation facility. Therefore, on the whole, patients with a diagnosis of PD were discharged to nursing homes almost twice as often as were non-affected hip fracture patients. This difference was most likely due to the small number of patients included and was not statistically significant (p = 0.246). Nevertheless, these findings are in accordance with the observations of Idjadi et al., who also examined geriatric hip fracture patients with PD [14]. Also in that patient sample, PD patients were more likely to be discharged to a skilled nursing facility than were controls.

Limitations

Although the present study was carefully designed, the results must be interpreted within the context of several limitations. First, the results are from an observational study; thus, conclusions cannot be drawn in terms of causality, and the relationships described can only be interpreted as associations. The present study examined and followed 402 prospectively enrolled patients with hip fractures, which makes it a large study as compared to other single-center studies investigating this topic [13, 28, 29]. This study was planned and designed as a long-term follow-up of patients with hip fractures, and only 19 patients with a concomitant diagnosis of PD were included. Nevertheless, a rate of approximately 5 % of PD patients, as observed in the present study, is within the range of other observational studies examining hip fracture patients [13, 14, 30, 31].

Second, the use of the H&Y scale as the only tool for PD staging might not have captured the full complexity of the disease. By focusing on the issues of unilateral vs. bilateral disease and the presence or absence of postural reflex impairment, other aspects of PD were left unassessed [32]. Additionally, according to the German guidelines for the diagnosis and therapy of PD, in addition to the H&Y scale, other staging tools (e.g., the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS)) are recommended [33]. Nevertheless, the H&Y scale was selected because it is simple and easy to apply. Furthermore, it is the most widely accepted and used clinical standard, allowing excellent comparability with previously published studies.

Conclusion

PD on hospital admission was not an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality or an inferior functional outcome in patients on discharge from acute hospital care. However, patients with PD are at a higher risk for specific complications and longer hospital stays following hip fracture also favoring reduced medium-term results in BI. Awareness of these complications may help caregivers reduce postoperative morbidity and decrease the length of hospitalization.

References

Hu F, Jiang C, Shen J, Tang P, Wang Y (2012) Preoperative predictors for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury 43(6):676–685. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2011.05.017

Kates SL, Behrend C, Mendelson DA, Cram P, Friedman SM (2015) Hospital readmission after hip fracture. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 135(3):329–337. doi:10.1007/s00402-014-2141-2

Becker C, Gebhard F, Fleischer S, Hack A, Kinzl L, Nikolaus T et al (2003) Prediction of mortality, mobility and admission to long-term care after hip fractures. Unfallchirurg 106(1):32–38. doi:10.1007/s00113-002-0475-7

Vochteloo AJ, van Vliet-Koppert ST, Maier AB, Tuinebreijer WE, Röling ML, de Vries MR et al (2012) Risk factors for failure to return to the pre-fracture place of residence after hip fracture: a prospective longitudinal study of 444 patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 132(6):823–830. doi:10.1007/s00402-012-1469-8

O’Malley NT, Blauth M, Suhm N, Kates SL (2011) Hip fracture management, before and beyond surgery and medication: a synthesis of the evidence. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 131(11):1519–1527. doi:10.1007/s00402-011-1341-2

Eschbach DA, Oberkircher L, Bliemel C, Mohr J, Ruchholtz S, Buecking B (2013) Increased age is not associated with higher incidence of complications, longer stay in acute care hospital and in hospital mortality in geriatric hip fracture patients. Maturitas 74(2):185–189. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.11.003

Chen YY, Cheng PY, Wu SL, Lai CH (2012) Parkinson’s disease and risk of hip fracture: an 8-year follow-up study in Taiwan. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 18(5):506–509. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.01.014

Schneider JL, Fink HA, Ewing SK, Ensrud KE, S. R., & Group, S. o. O. F. S. R (2008) The association of Parkinson’s disease with bone mineral density and fracture in older women. Osteoporos Int 19(7):1093–1097. doi:10.1007/s00198-008-0583-5

Bhattacharya RK, Dubinsky RM, Lai SM, Dubinsky H (2012) Is there an increased risk of hip fracture in Parkinson’s disease? A nationwide inpatient sample. Mov Disord 27(11):1440–1443. doi:10.1002/mds.25073

van den Bos F, Speelman AD, Samson M, Munneke M, Bloem BR, Verhaar HJ (2013) Parkinson’s disease and osteoporosis. Age Ageing 42(2):156–162. doi:10.1093/ageing/afs161

von Campenhausen S, Bornschein B, Wick R, Bötzel K, Sampaio C, Poewe W et al (2005) Prevalence and incidence of Parkinson’s disease in Europe. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 15(4):473–490. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.007

Walker RW, Chaplin A, Hancock RL, Rutherford R, Gray WK (2013) Hip fractures in people with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: incidence and outcomes. Mov Disord 28(3):334–340. doi:10.1002/mds.25297

Yuasa T, Maezawa K, Nozawa M, Kaneko K (2013) Surgical outcome for hip fractures in patients with and without Parkinson’s disease. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 21(2):151–153

Idjadi JA, Aharonoff GB, Su H, Richmond J, Egol KA, Zuckerman JD et al (2005) Hip fracture outcomes in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 34(7):341–346

Clubb VJ, Clubb SE, Buckley S (2006) Parkinson’s disease patients who fracture their neck of femur: a review of outcome data. Injury 37(10):929–934. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2005.11.013

http://www.asahq.org/clinical/physicalstatus.html, A. A. A. p. s. c. s. Accessed June 10 2014

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12(3):189–198

Lübke N, Meinck M, Von Renteln-Kruse W (2004) The Barthel Index in geriatrics. A context analysis for the Hamburg Classification Manual. Z Gerontol Geriatr 37(4):316–326. doi:10.1007/s00391-004-0233-2

Hoehn MM, Yahr MD (1967) Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 17(5):427–442

Tinetti ME (1986) Performance-oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 34(2):119–126

Podsiadlo D, Richardson S (1991) The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 39(2):142–148

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD et al (2009) The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 250(2):187–196. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2

Gosch M, Talasz H, Nicholas JA, Kammerlander C, Lechleitner M (2015) Urinary incontinence and poor functional status in fragility fracture patients: an underrecognized and underappreciated association. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 135(1):59–67. doi:10.1007/s00402-014-2113-6

Weber M, Cabanela ME, Sim FH, Frassica FJ, Harmsen WS (2002) Total hip replacement in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Int Orthop 26(2):66–68

Winge K, Nielsen KK (2012) Bladder dysfunction in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Neurourol Urodyn 31(8):1279–1283. doi:10.1002/nau.22237

King LA, Priest KC, Nutt J, Chen Y, Chen Z, Melnick M et al (2014) Comorbidity and Functional Mobility in Persons with Parkinson Disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2014.07.396

Derry CP, Shah KJ, Caie L, Counsell CE (2010) Medication management in people with Parkinson’s disease during surgical admissions. Postgrad Med J 86(1016):334–337. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2009.080432

Donegan DJ, Gay AN, Baldwin K, Morales EE, Esterhai JL, Mehta S (2010) Use of medical comorbidities to predict complications after hip fracture surgery in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am 92(4):807–813. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00571

Muhm M, Hillenbrand H, Danko T, Weiss C, Ruffing T, Winkler H (2013) Early complication rate of fractures close to the hip joint : dependence on treatment in on-call services and comorbidities. Unfallchirurg. doi:10.1007/s00113-013-2502-2

Roche JJ, Wenn RT, Sahota O, Moran CG (2005) Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ 331(7529):1374. doi:10.1136/bmj.38643.663843.55

Goetz CG, Poewe W, Rascol O, Sampaio C, Stebbins GT, Counsell C et al (2004) Movement Disorder Society Task Force report on the Hoehn and Yahr staging scale: status and recommendations. Mov Disord 19(9):1020–1028. doi:10.1002/mds.20213

(AWMF), A. W. M. F. (2012). S2 k Guideline Parkinson syndrome—diagnostics and therapy. Accessed 27 November 2014

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Lutz Waschnick, Natalie Schubert, Anna Waldermann, Kristin Horstmann, and Anne Hemesath, all of whom contributed to data acquisition. Richard Dodel is acknowledged for contributions to the conception and design of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

No particular funding was received for this work.

Conflict of interest

The corresponding author declares on behalf of all authors that there are no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bliemel, C., Oberkircher, L., Eschbach, DA. et al. Impact of Parkinson’s disease on the acute care treatment and medium-term functional outcome in geriatric hip fracture patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 135, 1519–1526 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-015-2298-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-015-2298-3