Abstract

Introduction

The incidence and natural course of pseudotumors in metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasties is largely unknown. The objective of this study was to identify the true incidence and risk factors of pseudotumor formation in large head metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasties.

Materials and methods

Incidence, time course and risk factors for pseudotumor formation were analysed after large femoral head MoM-THA. We defined a pseudotumor as a (semi-)solid or cystic peri-prosthetic soft-tissue mass with a diameter ≥2 cm that could not be attributed to infection, malignancy, bursa or scar tissue. All patients treated in our clinic with MoM-THA’s were contacted. CT scan, metal ions and X-rays were obtained. Symptoms were recorded.

Results

After median follow-up of 3 years, 706 hips were screened in 626 patients. There were 228 pseudotumors (32.3 %) in 219 patients (35.0 %). Pseudotumor formation significantly increased after prolonged follow-up. Seventy-six hips (10.8 %) were revised in 73 patients (11.7 %), independent risk factors were identified. Best cutoff point for cobalt and chromium was 4 μg/l (68 and 77 nmol/l).

Conclusions

This study confirms a high incidence of pseudotumors, dramatically increasing after prolonged follow-up. Risk factors for pseudotumors are of limited importance. Pain was the strongest predictor for pseudotumor presence; cobalt chromium and swelling were considered poor predictors. Cross-sectional imaging is the main screening tool during follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Large head metal-on-metal (MoM) bearings for total hip arthroplasty (THA) have purported advantages over conventional articulations such as lower wear rates, increased range of motion and increased stability which have made them a popular solution in the young and active patient with osteoarthritis of the hip [1, 2]. Although good clinical results and survival have been reported at medium-term follow-up [3], serious adverse reactions to metal debris (ARMD) leading to early failure and the formation of pseudotumors as well as systemic toxicity of increased systemic levels of chromium (Cr) and cobalt (Co) have been described [4–6]. Since 2010, metal-on-metal hip articulations have been on increased scrutiny from governmental regulatory agencies and national and international societies leading to alerts, advices and post marketing surveillance up to outright discontinuation of metal-on-metal devices [7–9]. Metal debris is thought to be generated by the articulation and/or the taper adapter interface depending on the model of prosthesis used. The exact mechanism of local and systemic metal release is yet not fully understood. Pseudotumors can be granulomatous or cystic lesions, neither infective nor neoplastic, which develop in the vicinity of the total hip arthroplasty. They can be large or small in size with or without communication to the joint. The lesion is supposedly progressive. It can cause pain, swelling, pressure effects, subluxation, bone and soft-tissue destruction and can as well be asymptomatic. Revision arthroplasty is advised in case of symptoms and/or tissue destruction [10]. We previously reported on a smaller prospectively followed subset of our patients and found a very high incidence of pseudotumors [6]. In the present study, we applied a comprehensive screening protocol to all our patients to confirm the high incidence of pseudotumors and identify risk factors for pseudotumor formation. The time course of pseudotumor formation and revision rate due to ARMD was assessed. Finally, we aimed to establish an optimal cutoff point for metal ion blood levels as a predictor for presence of local tissue reactions in patients treated with large head metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty.

Materials and methods

From January 2005 to July 2010 a Bi-Metric porous-coated uncemented stem with a metal-on-metal M2a-Magnum femoral head and ReCap acetabular component (Biomet, Warsaw, Indiana) was used in our facility. It was applied in relatively young and active patients, accounting for about 15 % of all our THAs in that period.

We performed a retrospective study on a prospective cohort to identify the incidence and risk factors of pseudotumors in patients treated with large-diameter modular MoM total hip prostheses.

Implant details

A large-diameter modular MoM prosthesis of a single design was used in all cases. The M2a Magnum bearing articulation consists of a monoblock press-fit cobalt chrome molybdenum cup articulating against a cobalt chrome molybdenum head, which is mounted on the stem taper (12/14) via a taper adapter. The head and acetabular component is high-carbon, as-cast (single heated) components. The system is modular, with increasing head size and concomitant larger shell size and the option to adapt the neck length using different length taper adaptors. The stem, taper and taper adapter are made of a titanium, aluminium and vanadium alloy (Ti6Al4V). The radial clearance level of the M2a-Magnum articulation is maintained at 75–150 μm [11]. The acetabular component is 6 mm thick at the dome and approximately 3 mm at the rim.

Patients

After obtaining ethical approval (IRB Isala Clinics Zwolle, 2010), all patients treated with the implant were contacted and invited for in-hospital screening. This study population includes the prospective subset of 120 patients screened in 2010 of which we have reported in a previous publication [6]. All other patients were screened for the presence of a pseudotumor in 2011. The latest clinical (revision) follow-up extends to April 2013.

Methods

Patients were questioned about symptoms in the groin, buttock, thigh and leg, such as pain, swelling, discomfort, numbness, and sensations of subluxation and clicking. Pain was also recorded on a visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from no pain (0) to extreme pain [10]. Patients were questioned about their use of vitamin supplements and possible history of allergies. All patients underwent pelvic (pubis centred) and hip (both hip and axially centred) radiographs. The angle of inclination of the acetabular component and centre line–edge distance (wedge, covering distance) was assessed. In addition, each patient underwent CT evaluation of the pelvis and knee to detect periarticular masses. The pseudotumors were measured on a calibrated scale, and the maximum diameter was recorded. Anteversion of the femoral component relative to the retrocondylar axis of the knee and anteversion of the acetabular component was measured. Two radiologists (MFB, MM) independently evaluated all CT scans for the presence of pseudotumor, obtaining consensus when results did not match. We defined a pseudotumor as a (semi-)solid or cystic peri-prosthetic soft-tissue mass with a diameter ≥2 cm that could not be attributed to infection, malignancy, bursa or scar tissue [6]. Laboratory analysis with atomic mass absorption spectrometry of whole blood levels of cobalt and chromium ions was performed at the time of CT evaluation. Blood samples were collected according to recent guidelines [12]. Serum levels of leucocytes, ESR, CRP, creatinine and urea were also analysed to screen for infection and renal impairment.

Statistical analysis

Analyses of survival included the computation of hazard ratios and the estimation of survival functions. Kaplan–Meyer procedure was used to estimate survival curves. Based on a backward selection procedure, Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was conducted to identify significant risk factors for pseudotumor and revision (p in/out = 0.05).

Differences in follow-up time were tested using Mann–Whitney U test. Pearson correlation coefficients were used for collinearity analyses. Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curves were constructed to define the best cutoff point for blood levels with the highest cumulative sensitivity and specificity of cobalt and chromium. A two-sided p value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

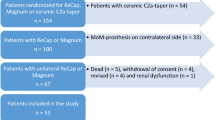

From January 2005 to July 2010, a total of 643 patients were treated with 723 MoM total hip arthroplasties. At the time of CT-follow-up, 5 patients had died and 12 patients refused further follow-up (3 were terminally ill, 9 for other reasons). A total of 626 patients with 706 hips were available for review. Of these patients, 15 were not eligible for follow-up because hip revision surgery had already been performed. Metal ion levels were not obtained in these and two additional patients. The trial profile is shown in Fig. 1.

Patient and implant characteristics with bivariate risk factor analyses for pseudotumor formation are shown in Table 1.

There were 228 pseudotumors (32.3 %) in 219 patients (35.0 %). The median follow-up of the entire cohort was 3.0 (0.3–6.1) years where CT scan indicated the end of follow-up. When a pseudotumor was present, follow-up was significantly longer (median 3.5 versus 2.8 years, p < 0.01).

The median of the largest diameter was 5.4 cm (2.0–12.9 cm). Pseudotumor size was 2–4 cm (n = 35, 15.5 %), 4–8 cm (n = 154, 68.1 %) or 8 cm and more (n = 37, 16.4 %). Distribution of size is further illustrated in Fig. 2.

Tumour location correlated significantly to surgical approach (p < 0.01, Table 2).

Seventy-six hips (10.8 %) have been revised in 73 patients (11.7 %) after a median period of 5.3 (1.0–8.3) years.

Kaplan–Meyer plots for estimating survival are shown in Fig. 3a (pseudotumor-free survival) and 3b (revision-free survival).

Multivariate risk factor analyses identified the following independent risk factors for the presence of a pseudotumor: pain, cobalt ≥4 µg/l (68 nmol/l), and swelling (Table 3).

No clear relation between acetabular component orientation and pseudotumor formation could be observed (Fig. 4) or between pseudotumor formation and component size. Collinearity analysis revealed that cobalt and chromium levels were highly associated (Pearson’s r = 0.932, p < 0.01). We found 4 µg/l (68 and 77 nmol/l) to be the “best” cutoff point for cobalt and chromium (sensitivity 57.1 and 54.6 %, specificity 70.6 and 65.8 %, Table 4).

Discussion

This study shows a dramatic increase of pseudotumors in patients treated with large head metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasties after prolonged follow-up. Pain was the strongest independent predictor for pseudotumor presence, followed by clinical swelling and cobalt ≥4 µg/l (68 nmol/l). Associated risk factors for pseudotumor formation, however, seem of limited importance leaving cross-sectional imaging as the main screening tool during follow-up.

Study population

The high incidence of pseudotumors in our study might be explained by the study population. Patients examined were both symptomatic and asymptomatic. The generally lower incidence reported in literature is mostly based on symptomatic patients only [13–15]. A more comparable incidence (25–61 %) is found in similar studies investigating both asymptomatic and symptomatic patients [16–18].

Implant design

Implant design potentially influences pseudotumor incidence. Various models of metal-on-metal THAs generate different amounts of wear probably influencing the occurrence of metal debris-associated problems. A large modular femoral head (≥36 mm), as used in our patients is considered to be a risk factor for developing ARMD [2].

Pseudotumor

The definition of a pseudotumor, as stated in our study, might contribute to the high incidence. We believe that a lesion as small as 2 cm in diameter that cannot be explained by other causes, can be accurately diagnosed on CT as a pseudotumor [6]. Most pseudotumors in our study were considerably larger, measured by their maximum diameter and not in volume. Although associated with implant failure, the clinical relevance of the asymptomatic lesions, especially the smaller ones, is still subject to discussion. Longer follow-up of these smaller lesions is needed [17].

Imaging techniques

CT was used as a screening instrument. We believe that CT, despite scattering artifacts caused by the large metal implant, provides adequate diagnostic images with the added benefit that it allows measurement of component orientation [19]. A CT scan is less expensive and more readily available than metal artifact reduction scanning (MARS) MRI. CT scanning was preferred over ultrasound (US) because of the more limited interobserver bias.

In accordance to our study, several authors found that patients with pseudotumors often present with pain or discomfort [10, 20]. One study found that the first clinical sign of a pseudotumor was usually pain, which led to radiographic examination and detection of lesions around the prosthetic stem [21]. Other studies have identified osteolytic areas as a precursor to pseudotumors [22]. Osteolysis was much more frequently found on CT scans than on X-rays in our study, adding a possible additional benefit to CT as a screening device.

Risk factors

Associations of cup malposition with increased release of metal wear debris [23–25] and with increased component wear rates and pseudotumor formation have been reported [26, 27]. Cup position in our study, however, could not be pointed out as an independent risk factor. This is in line with several other publications suggesting that pseudotumors are also common in patients with asymptomatic MoM-THA [28] and in patients with low metal ion levels and a well-positioned cup [29, 30]. A substantial fraction of our acetabular components was placed outside Lewinnek’s safe zone. This is in line with literature on free hand cup positioning [31]. Furthermore, in different ranges for combined anteversion (cup plus stem) a risk factor could not be identified. This and the comparable results of similar studies [29, 30] might indicate that orientation of components plays a less important role in pseudotumor formation than previously suggested.

Several other risk factors for pseudotumors, as described in literature (female gender, swelling, clicking sensations and femoral head size), [27, 32] could not be confirmed as an independent risk factor for developing a pseudotumor in our multivariate analysis.

To the best of our knowledge, a relation between pseudotumor location and surgical approach has not previously been reported in literature. The pseudotumors seem to follow the route of the chosen surgical approach, possibly due to decreased tissue resistance caused by the former dissection. The Kaplan–Meyer plot for pseudotumor formation demonstrates that most of our patients will develop a pseudotumor. Obviously, since the Kaplan–Meyer plot is an estimation based on patients with a broad range of follow-up, the actual increase in the incidence of detectable pseudotumors has to be confirmed in a future follow-up of our cohort of patients.

Revisions

The revision rate in our series was 10.8 % at a median follow-up of 5.3 years, increasing over time. Pain combined with the presence of a pseudotumor on CT was the main indication.

Early detection of pseudotumors is important because it is generally agreed that if revision surgery is performed in patients before substantial soft-tissue damage has occurred, the outcome is likely to be better [33]. If substantial tissue damage has already occurred, then revision surgery is associated with poor function and more complications [34].

Metal ions

Whole blood cobalt and chromium levels were mutually related. Although metal ions were on average higher when a pseudotumor was present, they are poor predictors (sensitivity 57.1 and 54.6 %, specificity 70.6 and 65.8 %).

We tried to identify if there was a value of blood metal ions below which the presence of a pseudotumor was unlikely. A very high sensitivity would be required. For cobalt, an appropriate threshold value would be 1 µg/l (17 nmol/l) (sensitivity 97.7, specificity 11.0 %). Using this threshold, cobalt would have saved the need for 47 of 609 CTs (8 %) and we would still have missed 3 pseudotumors.

Although its use for predicting the presence of a pseudotumor is limited, a (sudden) increase of blood metal ions is reported to be associated with implant failure [35]. Furthermore, several studies report about toxic effects of prolonged elevated systemic metal ion exposure and, therefore whole blood metal ion testing should have a place in follow-up. Health risks that are related to chronically elevated blood cobalt concentrations are: hypothyroidism, polyneuropathy, impairment of cranial nerves II and VIII and cardiomyopathy [36]. Others report concerns about carcinogenicity, hypersensitivity and foetal exposure in pregnant women [37–39]. Chronic exposure to low-elevated metal concentrations in patients with MoM hip resurfacings may have systemic effects and long-term epidemiological studies in large populations, such as those available through joint registries are needed [40].

Conclusion and recommendations

This study shows a very high incidence of pseudotumors in patients treated with large head metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty at short-term follow-up. Time course analysis estimates that the fair share of our patients is likely to develop a pseudotumor in the near future. Several risk factors for developing a pseudotumor were identified, but their clinical relevance is limited. Cobalt and chromium are poor predictors for pseudotumor presence, importantly pain seems to be the most important predictor and hence further investigations are warranted. Even in the presence of normal ion levels, imaging is considered mandatory.

We recommend an annual follow-up of all patients subjected to a large diameter femoral head metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty for as long as the prosthesis is in situ. Routine X-rays and imaging techniques like MARS MRI or CT should be performed and probably repeated to assess pseudotumor formation in all patients. Further research is needed to show if and when the intensified follow-up can be returned to a more routine schedule.

References

Girard J, Bocquet D, Autissier G et al (2010) Metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty in patients thirty years of age or younger. J Bone Joint Surg Am 92(14):2419–2426

Hannemann F, Hartmann A, Schmitt J et al (2013) European multidisciplinary consensus statement on the use and monitoring of metal-on-metal bearings for total hip replacement and hip resurfacing. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 99(3):263–271

Haddad FS, Thakrar RR, Hart AJ et al (2011) Metal-on-metal bearings: the evidence so far. J Bone Joint Surg Br 93(5):572–579

Ollivere B, Darrah C, Barker T, Nolan J, Porteous MJ (2009) Early clinical failure of the Birmingham metal-on-metal hip resurfacing is associated with metallosis and soft-tissue necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 91(8):1025–1030

Smith AJ, Dieppe P, Vernon K, Porter M, Blom AW (2012) Failure rates of stemmed metal-on-metal hip replacements: analysis of data from the National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Lancet 379(9822):1199–1204

Bosker BH, Ettema HB, Boomsma MF, Kollen BJ, Maas M, Verheyen CC (2012) High incidence of pseudotumour formation after large-diameter metal-on-metal total hip replacement: a prospective cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 94(6):755–761

No authors listed 1. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Medical device alert: all metal-on-metal (MoM) hip replacements. http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Publications/Safetywarnings/MedicalDeviceAlerts/CON155761. Accessed 02 Sep 2013

No authors listed 2. U.S. Food and drug administration: Metal-on-metal hip implants. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/MetalonMetalHipImplants/default.htm. Accessed 02 Sep 2013

Verheyen CC, Verhaar JA (2012) Failure rates of stemmed metal-on-metal hip replacements. Lancet 380(9837):105 (author reply 106)

Daniel J, Holland J, Quigley L, Sprague S, Bhandari M (2012) Pseudotumors associated with total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 94(1):86–93

No authors listed 3. Biomet: M2a-Magnum large metal articulation: design rationale 2009. http://www.biomet.com/campaign/trueAlternativeBearings/BOI03400MagnumDesignRationale.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2012

MacDonald SJ, Brodner W, Jacobs JJ (2004) A consensus paper on metal ions in metal-on-metal hip arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty 19:12–16

Canadian Hip Resurfacing Study Group (2011) A survey on the prevalence of pseudotumors with metal-on-metal hip resurfacing in Canadian academic centers. J Bone Joint Surg Am 93(Suppl 2):118–121

Campbell P, Shimmin A, Walter L, Solomon M (2008) Metal sensitivity as a cause of groin pain in metal- on-metal hip resurfacing. J Arthroplasty 23:1080–1085

Malviya A, Holland JP (2009) Pseudotumours associated with metal-on-metal hip resurfacing: 10-year Newcastle experience. Acta Orthop Belg 75(4):477–483

Williams DH, Greidanus NV, Masri BA, Duncan CP, Garbuz DS (2011) Prevalence of pseudotumor in asymptomatic patients after metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 93(23):2164–2171

Hart AJ, Satchithananda K, Liddle AD et al (2012) Pseudotumors in association with well-functioning metal-on-metal hip prostheses: a case-control study using three-dimensional computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Bone Joint Surg Am 94(4):317–325

van der Weegen W, Smolders JM, Sijbesma T, Hoekstra HJ, Brakel K, van Susante JL (2013) High incidence of pseudotumours after hip resurfacing even in low risk patients; results from an intensified MRI screening protocol. Hip Int 23(3):243–249

Ghelman B, Kepler CK, Lyman S, González Della Valle AG (2009) CT outperforms radiography for determination of acetabular cup version after THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res 467:2362–2370

Counsell A, Heasley R, Arumilli B, Paul A (2008) A groin mass caused by metal particle debris after hip resurfacing. Acta Orthop Belg 74:870–874

Tallroth K, Eskola A, Santavirta S, Konttinen YT, Lindholm TS (1989) Aggressive granulomatous lesions after hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 71:571–575

Wirta J, Eskola A, Santavirta S, Tallroth K, Konttinen YT, Lindholm S (1990) Revision of aggressive granulomatous lesions in hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 5(Suppl):S47–S52

De Haan R, Pattyn C, Gill HS, Murray DW, Campbell PA, De Smet K (2008) Correlation between inclination of the acetabular component and metal ion levels in metal-on-metal hip resurfacing replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 90(10):1291–1297

Langton DJ, Sprowson AP, Joyce TJ et al (2009) Blood metal ion concentrations after hip resurfacing arthroplasty: a comparative study articular surface replacement and Birmingham hip resurfacing arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Br 91:1287–1295

Matthies A, Underwood R, Cann P et al (2011) Retrieval analysis of 240 metal-on-metal hip components, comparing modular total hip replacement with hip resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg Br 93:307–314

Kwon YM, Glyn-Jones S, Simpson DJ et al (2010) Analysis of wear of retrieved metal-on-metal hip resurfacing implants revised due to pseudotumours. J Bone Joint Surg Br 92(3):356–361

Langton DJ, Jameson SS, Joyce TJ, Hallab NJ, Natu S, Nargol AV (2010) Early failure of metal-on-metal bearings in hip resurfacing and large-diameter total hip replacement: a consequence of excess wear. J Bone Joint Surg Br 92(1):38–46

Kwon YM, Ostlere SJ, McLardy-Smith P et al (2011) “Asymptomatic” pseudotumors after metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty: prevalence and metal ion study. J Arthroplasty 26:511–518

Donell ST, Darrah C, Nolan JF, Metal-on-Metal Study Group, Norwich Metal-on-Metal Study Group et al (2010) Early failure of the Ultima metal-on-metal total hip replacement in the presence of normal plain radiographs. J Bone Joint Surg Br 92:1501–1508

Matthies AK, Skinner JA, Osmani H, Henckel J, Hart AJ (2012) Pseudotumors are common in well-positioned low-wearing metal-on-metal hips. Clin Orthop Relat Res 470(7):1895–1906

Saxler G, Marx A, Vandevelde D et al (2004) The accuracy of free-hand cup positioning-a CT based measurement of cup placement in 105 total hip arthroplasties. Int Orthop 28(4):198–201

Glyn-Jones S, Pandit H, Kwon YM, Doll H, Gill HS, Murray DW (2009) Risk factors for inflammatory pseudotumour formation following hip resurfacing. J Bone Joint Surg Br 91(12):1566–1574

Sandiford NA, Muirhead-Allwood SK, Skinner JA (2010) Revision of failed hip resurfacing to total hip arthroplasty rapidly relieves pain and improves function in the early post-operative period. J Orthop Surg Res 5:88

Grammatopolous G, Pandit H, Kwon YM et al (2009) Hip resurfacings revised for inflammatory pseudotumour have a poor outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br 91:1019–1024

Langton DJ, Sidaginamale RP, Joyce TJ et al (2013) The clinical implications of elevated blood metal ion concentrations in asymptomatic patients with MoM hip resurfacings: a cohort study. BMJ Open 3(3):e001541

Campbell JR, Estey MP (2013) Metal release from hip prostheses: cobalt and chromium toxicity and the role of the clinical laboratory. Clin Chem Lab Med 51(1):213–220

Hasegawa M, Yoshida K, Wakabayashi H, Sudo A (2012) Cobalt and chromium ion release after large-diameter metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 27(6):990–996

Visuri T, Pukkala E, Paavolainen P, Pulkkinen P, Riska EB (1996) Cancer risk after metal on metal and polyethylene on metal total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res (329 Suppl):S280–9

Ziaee H, Daniel J, Datta AK, Blunt S, McMinn DJ (2007) Transplacental transfer of cobalt and chromium in patients with metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty: a controlled study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 89(3):301–305

Prentice JR, Clark MJ, Hoggard N et al (2013) Metal-on-metal hip prostheses and systemic health: a cross-sectional association study 8 years after implantation. PLoS One 8(6):e66186

Conflict of interest

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bosker, B.H., Ettema, H.B., van Rossum, M. et al. Pseudotumor formation and serum ions after large head metal-on-metal stemmed total hip replacement. Risk factors, time course and revisions in 706 hips. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 135, 417–425 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-015-2165-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-015-2165-2