Abstract

This case report of a 61-year-old woman suffering from Gorham–Stout syndrome shows osteolyses of the left pelvis, proximal femur and lumbar spine. The therapeutic regime has included two courses of percutaneous radiotherapy and also continuous application of bisphosphonates over 17 years. Despite this antiresorptive therapy, elevated urinary excretion of desoxypyridinoline has indicated the persistence of increased bone destruction. The radiological progression following bisphosphonate treatment was only moderate. However, physical disability is reduced, but without soaring handicaps suggesting that long-term bisphophonate therapy is a therapeutical option for this rare syndrome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gorham–Stout disease (GSD) is a rare disorder characterized by progressive osteolysis with invasion of the surrounding soft tissue. Until now, less than 200 cases were published. The first case reported by Jackson [1] in 1883 as “A boneless arm” described a 12-year-old boy with advanced osteolysis of the humerus. In 1955, Gorham and Stout developed histopathological criteria of the disease based on their own experience and the literature findings as follows: “Gorhams’s disease is usually associated with an angiomatosis of blood vessels and sometimes of lymphatic vessels, which seemingly are responsible for it [2]. Actually etiology and pathophysiology remain poorly understood. The disease may affect every bone, but shoulder and pelvis are the most common manifestations. Prognosis and complications widely vary depending on the site and extent of bone destruction. Treatment options include radiation therapy and surgical procedures and with respect to increased osteoclastic activity the systemic use of bisphosphonates.

Case report

A 61-year-old woman, who complained accentuated rest pain of the left pelvis and femur increasing in motion for approximately 10 months, was admitted in 1989. Radiographs revealed osteolytic lesions around a fracture involving os ischii and os ilii showing a delayed fracture healing after a sudden fall. Gorham–Stout syndrome was diagnosed based on synopsis of typical radiological and histological findings. Radiological characteristics verified a reduced progress of bone destruction under bisphosphonates combined with a gain of soft tissue involvement and formation of a cutaneous fistula.

Histological findings

Bone biopsy from os ilium taken in 1989 demonstrated increased bone turnover with numerous empty and osteoclast covered resorption cavities around the trabecular surface. Wide, thin-walled and blood-filled capillaries in the intertrabecular spaces could be described (Fig. 1).

Current physical examination

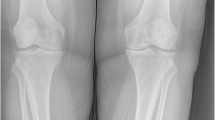

The patient is unable to stand straight without support, the gait is limping. The left leg is endorotated and is shortened when compared to the right site by approximately 5 cm (Fig. 2a, b). Trendelenburg’s sign is positive. A smooth tissue swelling above the greater trochanter massif offers a central orificium of a fistula (Fig. 2c). Clinical examination of heart and lung revealed no pathological findings; the blood pressure was normal (125/80 mmHg, puls 72/min), clinical investigation of the abdomen was normal, and no resistances and no enlargement of liver or spleen were detectable. Clinical spine examination was limited due to unstable standing ability caused by shortened left leg. Besides the gait problem, clinical neurological investigation showed no abnormalities. Furthermore, there were no concomitant diseases.

Laboratory parameters

Marked elevation of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (75/96 mm, normal <7/18 mm) and C-reactive protein (51 mg/ml, normal <5 mg/ml) were present. These values completely normalized after spontaneous draining of the fistula. The excreted fluid was lucent, yellow and of low viscosity. No bacteria were detectable by light microscopic analysis and culture.

The bone degradation marker desoxipyridinolin (first evaluated in 2003) was two to threefold elevated (Fig. 3) during the course of the disease despite antiresorptive treatment. Parathormone levels varied in a wide range, without correlation to the increased excretion of desoxypyridinolin (Fig. 3).

Normal levels of vitamin D (25 hydroxycholecalciferol), osteocalcin and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase were measured over the whole observation period. There were no abnormalities in laboratory parameters associated with connective tissue diseases (no antinuclear antibodies, no reduction of complement factors), vasculitis diseases (no antineutrophil cytoplasmatic antibodies) or blood coagulation disorders (normal platelet count and normal thromboplastin time). Tuberculosis was ruled out by a negative Tine test and negative ELISPOT. There was no evidence for other infections and the procalcitonine level was normal.

Radiological investigations

The patient underwent a close meshed examination during the course of disease using spiral computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Between 1989 (Fig. 4a Somatom CR; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany, 8-mm section thickness, reconstruction with a slice thickness of 8 mm) and 2000 (Fig. 4b General electric, VCT, Waukesha, Wisconsin; USA, 16 × 1.25 mm collimation, 27.5 mm increment, pitch 55), the CT-scans of the hip revealed accentuated bone destruction that was reduced in its progression under bisphosphonates therapy illustrated in the CT-images from 2008 (Fig. 4c General Electric VCT, Waukesha, Wisconsin; USA, 64 × 1.25 mm collimation, 27.5 mm increment, pitch 55, overlapping reconstruction with a slice thickness of 1.25 mm). A 3D reconstruction facilitated the evidence of bone loss (Fig. 5).

a CT-scan of the pelvis (September 1989) demonstrates initial osteolysis of acetabulum as well as os ischii and still intact femoral head. b CT-scan of the pelvis (October 2000) shows progressive osteolysis of the proximal femur, acetabulum and iliac bone combined with an accumulation of soft tissue near the hip joint. c CT-scan of the pelvis (January 2008) visualizes a reduced progression of bone destruction, in particular regarding the acetabulum, but also offers an advanced soft tissue invasion compared to 2000

MRI (Siemens Sonata; 1.5 Tesla MRI scanner, Erlangen, Germany) visualized the progression of soft tissue involvement resulting in the advanced occurrence of a cutaneous fistula (Fig. 6a, b). Also the edematous involvement of the surrounding soft tissue near the left hip was increased following the gain of extraosseous tumor tissue (Fig. 7a, b).

a MRI-scan (coronal acquired T2-weighted sequence, November 2003) reveals the consecutive atrophy of the gluteal muscles on the left side caused by limited mobility and the first existence of a cutaneous fistula. b MRI-scan (coronal acquired T2-weighted sequence, March 2006) reveals the consecutive atrophy of the gluteal muscles on the left side and the accentuated persistence of a cutaneous fistula

a MRI-scan (axial acquired fluid sensitive sequence, November 2003) demonstrates the beginning of soft tissue involvement and tumor invasion of the soft tissue with mild edema. b MRI-scan (axial acquired fluid sequence, March 2006) shows the progression of soft tissue involvement and tumor invasion of the soft tissue with severe edema

Furthermore, the cranial subluxation of the proximal femur is accentuated between 2003 and 2006, combined with further bone destruction of the greater trochanter massif and femoral neck (Fig. 8a, b).

a MRI-scan (coronal acquired T2-weighted sequence, November 2003) reveals the consecutive atrophy of the ileopsoas and adductor muscles on the left side caused by limited mobility and the cranial subluxation of the proximal femur. Tumor tissue fills the acetabulum. b MRI-scan (coronal acquired T2-weighted sequence, March 2006) shows the increased atrophy of the ileopsoas and adductor muscles on the left side and the advanced cranial subluxation of the proximal femur. Tumor tissue fills the acetabulum in a progressive extent combined with a further destruction of the femoral neck as well as of the greater trochanter massif

Therapeutic procedures

Radiotherapy of left pelvis (40 Gray in 2 Gray fractions) was performed first in the year 1990. Bisphosphonate therapy was started on May 1992 with etidronate (400 mg/day). Due to increasing pain, localized in the pelvis and femur, therapy was switched to intermittent Clodronate per infusionem from December 1993 up to March 1995 (5 × 300 mg/day, monthly). Each of them resulted in a reduction of the complaints. Because of the decreasing analgesic capacity, oral clodronate medication (2 × 520 mg/d) was continued until December 2000 and subsequently until now with risedronate (35 mg once weekly). In 2006, a second radiotherapy (32 Gray in 2 Gray fractions) was initiated to stop the radiologically confirmed progress including the inflammatory involvement of soft tissue.

Concomitant therapies included temporary administration of NSAID’s (indometacine 150 mg/day or diclofenac/misoprostol 150/0.4 mg/day) and analgesics (flupirtinmaleat until 400 mg/day) as well as manual lymphatic drainage of the swollen femoral region.

The option of surgical treatment with reconstruction using a bone graft and/or prosthesis implantation was taken into consideration several times but the patient declined any surgical treatment.

Discussion

Gorham–Stout disease is a rare disorder characterized by an autonomous proliferation of vascular and lymphatic capillaries within bone and surrounding soft tissue with consecutive destruction [2]. The etiology of the disease is still unknown. Axial, as well as appendicular skeleton can be affected and lymphangiomatous extension from thoracic vertebrae, ribs or scapula may result in the development of chylothorax, a complication with high mortality [3–5]. Clinical manifestations vary and depend on the manifestation pattern. It often takes several months between first complaints and diagnostic confirmation. Typical histological findings include destruction of cortical and trabecular bone and replacement by widened, confluencing thin-walled vessels, infiltrating and destroying adjacent soft tissue without evidence of malignancy. Increased osteoclastic resorption is an inconstant finding [6, 7].

Similar to previously described cases [8, 9], GSD in our patient was diagnosed after a pathological fracture of the os ischii and os ilii. According to a metaanalysis, pelvis and proximal femur were involved in 12.9% of all published cases until 1989 [10–12]. As a consequence of the rarity of the disease, therapeutic recommendations do not exist.

Surgical strategies with resection of the Gorham lesions and reconstruction using bone grafts or prosthesis are reported [13–15]. Radiation therapy has been used with different success [3, 16, 17]. In a review by Dunbar et al. [18], 14 of 22 patients (64%) succeeded after administration of doses of 40–45 Gy at 1.8–2 Gy per each fraction. Especially in cases with pelvis and shoulder manifestations, radiation was suggested as first line therapy [19]. Our patient was treated twice with radiation therapy, with an interjacent period of 16 years. The cumulative dosages of 40 resp. 32 Gray were similar to the previously reported dosages [18]. Finally, the impact of the administered therapeutic procedures radiation and bisphosphonate therapy to slowdown the accelerated bone resorption cannot be differentiated. The ability of bisphosphonates to stabilize bony destruction has been reported by several authors [6, 20, 21]. Furthermore, spontaneous resolution in GSD has been described also [22, 23]. Our rationale for the long-standing continuous bisphosphonate application resulted from the sustained analgesic effect of the several admitted agents and the permanently increased excretion of desoxypyrodinolin in the course of the disease. In summary, this case report shows that a long-term bisphosphonate therapy over 17 years is feasible and can contribute to the clinical stabilization in Gorham’s disease.

References

Jackson JBS (1883) A boneless arm. Boston Med Surg J 18:368–369

Gorham WL, Stout AP (1955) Massive osteolysis (acute spontaneous absorption of bone, phantom bone, disappearing bone): its relation to hemangiomatosis. J Bone Joint Surg 37A:985–10004

Mc Neil KD, Fong KM, Walker QJ, Jessup P, Zimmerman PV (1996) Gorham’s syndrome: a usually fatal course of pleural effusion treated successfully with radiotherapy. Thorax 51:1275–1276

Feigl D, Seidel L, Marmor A (1981) Gorham’s disease of the clavicle with bilateral pleural effusions. Chest 79:242–244

Yoo SY, Goo JM, Im JG (2002) Mediastinal lymphangioma and chylothorax. Thoracic involvement of Gorham’s disease. Korean J Radiol 3:130–132

Hammer F, Kenn W, Wesselmann U, Hofbauer LC, Delling G, Allolio B, Arlt W (2005) Gorham Stout disease—stabilization of the disease during bisphosphonate treatment. J Bone Miner Res 20:350–353

Moller G, Priemel M, Amling M, Werner M, Kuhlmey AS, Delling G (1999) The Gorham–Stout Syndrome (Gorham’s massive osteolysis). A report of six cases with histopathological findings. J Bone Joint Surg Br 81:501–506

Cannon SR (1986) Massive Osteolysis—a review of seven cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 68:24–28

Schmitt O, Schmitt E, Biehl G (1982) Die essentielle Osteolyse Klinik und Verlauf eines seltenen Krankheitsbildes. Z Orthop 120:160–164

Kulenkampff HA, Richter GM, Haase WE, Adler CP (1990) Massive pelvic osteolysis in the Gorham Stout syndrome. Int Orthop (SICOT) 14:361–366

Kulenkampff HA, Richter GM, Adler C, P Haase WE (1989) Massive Osteolyse (Gorham Stout Syndrom) - Klinik, Diagnostik, Therapie und Prognose. Neuere Ergebnisse in der Osteologie. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 387–397

Hardegger F, Simpson LA, Segmueller G (1985) The syndrome of idiopathic osteolysis. Classification, review, and case report. J Bone Joint Surg Br 67:214–219

Paley MD, Lioyd CJ, Penfold CN (2004) Total mandibular reconstruction for massive osteolysis of the mandible (Gorham–Stout syndrome). Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 3(2):166–168

Poirer H (1968) Massive osteolysis of the humerus treated by resection and prosthetic replacement. J Bone Joint Surg 50 B:158–160

Woodward HR, Chan DPK, Lee J (1981) Massive osteolysis of the cervical spine. A case report of bone graft failure. Spine 6:545–549

Lee S, Finn L, Sze RW, Perkins JA, Sie KC (2003) Gorham Stout syndrome (disappearing bone disease): two additional case reports and review of the literature. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 129:1340–1343

Handl-Zeller L, Hohenberg G (1990) Radiotherapy of Morbus Gorham–Stout: the biological value of low irradiation dose. Br J Radiol 63:206–208

Dunbar SF, Rosenberg A, Mankin H, Rosenthal D, Siut HD (1993) Gorham`s massive osteolysis: the role of radiation therapy and a review of the literature. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 26:491–497

Hambach R, Pujman J, Mally V (1958) Massive osteolysis due to haemangiomatosis: report of a case of Gorham’s disease with autopsy. Radiology 71:43–47

Hagberg H, Lamberg K, Astrom G (1997) Alpha 2b-interferon and oral clodronate for Gorham’s disease. Lancet 350:1822–1823

Mignogna MD, Fedele S, Russo l Lo, Ciccarelli R (2005) Treatment of Gorham`s disease with zoledronic acid. Oral Oncol 41:747–750

Campbell J, Almond HG, Johnson R (1975) Massive osteolysis of the humerus with spontaneous recovery. J Bone Joint Surg Br 57:238–240

Boyer P, Bourgoeis P, Boyer O, Catonne Y, Saillant G (2005) Massive Gorham–Stout syndrome of the pelvis. Clin Rheumatol 24:551–555

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lehmann, G., Pfeil, A., Böttcher, J. et al. Benefit of a 17-year long-term bisphosphonate therapy in a patient with Gorham–Stout syndrome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 129, 967–972 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-008-0742-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-008-0742-3