Abstract

Introduction

Weight lifting is commonly associated with an increase in knee injury risk. Local steroid injection is thought to be associated with increased risk of spontaneous tendon rupture. The purpose of this report is to describe incidence of rupture of the patellar tendon after receiving multiple local steroid injections in weight lifters.

Materials and methods

Seven weight lifters presented at the hospital with ruptured patellar tendon. All the patients had a history of multiple local steroid injections into the patellar tendon. Each patient received surgical treatment within 72 h after injury.

Results

After an average follow-up time of 26 months, the mean postoperative Lysholm knee score was 94 and the mean Insall-Salvati measurement was 0.96. All seven athletes returned to weight lifting training at 1 year after the operation. They returned to full competition at 18 months after the surgery.

Conclusion

For physicians who treat patellar tendonitis, especially in weight lifters, it is important to recognize the contributing factors for tendon rupture especially in those who have had multiple steroid injections. The functional prognosis of the knee improves if the normal length and strength of the injured tendon have been properly restored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Patellar tendon rupture is a rare injury and occurs most commonly in younger population [25]. The clinical signs of patellar tendon rupture include weakness of knee joint extension, inability to walk, palpable infrapatellar defect and radiographic “patella alta” [5].The mechanism of patellar tendon rupture can be divided into direct injury, or high-velocity and low-velocity indirect injury [12]. Most patellar tendon ruptures occur as a low-velocity indirect injury after minor trauma with degenerative patellar tendon [25]. The possible risk factors causing patellar tendon degeneration include the systemic disorders (e.g., lupus erythematous, diabetes mellitus, rheumathoid arthritis, chronic renal failure) [30], jumper’s knee [9, 23], previous knee surgery (e.g., central one-third patellar tendon graft) [4] and local steroid injection [29].

Tendinopathies are mostly associated with the Achilles and patellar tendons [1, 6, 10, 13, 15, 16]. Local injection of steroid is a common method to treat such tendinopathies. The link of corticosteroids and tendinopathies with associated tendon ruptures was first reported 40 years ago [27]. To our knowledge, there was no literature regarding the relationship and treatment outcome of patellar tendon rupture in weight lifters. It is our belief that the spontaneous rupture of the tendon may be related to steroid injections used to treat a previous injury of that area. In this report, seven cases of rupture of the patellar tendon with a previous history of local steroid injections will be presented.

Materials and methods

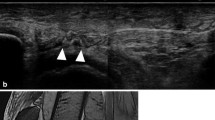

Between October 2002 and October 2004, seven weight lifters presented at the hospital with ruptured patellar tendons. The population included five men and two women, with a mean age of 22 years, ranging from 16 to 28 years. The average follow-up time was 26 months (range from 18 to 38 months). All the patients had a history of receiving local steroid injections into the knee. The average number of injections for each patient was nine with a range of 5–20 injections. Except for the use of steroids, none had systemic predisposing factors for tendon rupture. Physical examination reveals a defect in the patellar tendon (Fig. 1a) and it may rest more proximally than normal (Fig. 1b). Their original injuries were all due to athletic competition or training.

Each patient was brought to our facility with their latest injuries and each received surgical treatment within 72 h. After approached to the injured site, noted steroid deposits (Fig. 2a) and necrotic substances (Fig. 2b) were removed prior to suture repair. Surgical repair consists of a heavy nonabsorbable material, Ticron no. 5, woven through drill holes underneath the tibia tuberosity. Reattachment was completed to the patella through drill holes (Fig. 2c), and then reinforced using absorbable mixed nonabsorbable sutures around the area of rupture (Fig. 2d). The knee is then braced in an immobilizer or other brace and locked in extension. After approximately 6 weeks, supervised intensive rehabilitation protocol is initiated along with active flexion and extension exercises.

a Debridement of the steroid deposits and necrotic substances were the routine procedures before the sutures were performed. b Rupture end of patellar tendon contained the corticosteroids injection deposits. c Heavy nonabsorbable materials (Ticron no. 5) woven through the drill holes underneath tibia tuberosity, reattachment to the patella through drill holes. d Reinforcement using absorbable mixed nonabsorbable sutures around the torn area

Evaluation consisted of the Lysholm score, roentgenographic examination and physical examination of the injured knee. The Lysholm knee score [14] is a condition-specific outcome measure that contains eight domains: limp, locking, pain, stair-climbing, use of supports, instability, swelling and squatting. An overall score of 0–100 points is calculated, with 95–100 points indicating an excellent outcome; 84–94 points, a good outcome; 65–83 points, a fair outcome; and <65 points, a poor outcome. The lateral view of knee radiography with 20°–30° of flexion was taken to determine the height of patella using the Insall-Salvati measurement (length patella/length tendon (LP/LT); normal range 0.8–1.2) [8]. The physical examination consisted of range of motion, residual deformity and muscle power. A Biodex 3® isokinetic dynamometer (Biodex Medical Systems Inc., Shirley, NY, USA) was used for the measurement of muscle power. For each subject, the knee extension and flexion patterns were tested at 60, 180 and 240°/s angular velocities. Dominant side was first measured followed by the contra lateral side. Peak torque, peak torque/body weight, maximal repetition total work, work/body weight and agonist/antagonist ratio isokinetic scores were recorded for each velocity. The reference position (90°flexion) was recorded. The amplitude of the range of motion (ROM) varied from 80° to 100°. Between each condition, the subject was allowed to rest for 1 min, and gravitational corrections were performed.

Results

All seven patients were included in the follow-up examination. The average follow-up time was 26 months. The mean Lysholm knee score at the time of follow-up was 94 (range 91–99). Five cases were graded as excellent outcome, and two cases were graded as good outcome. The mean Insall-Salvati measurement was 0.96 (range 0.92–1.02). All patients regained full range of motion as the contra lateral one at the time of follow-up. The difference of muscle power between the operated and control knee at the time of follow-up was as follows: a mean loss of 8% in extension (quadriceps) strength (range 4–15) when measuring concentric extension and a mean loss of 3% in flexion (Hamstring) strength (range 2–6) in concentric flexion. All seven athletes returned to weight lifting training at 1 year after the operation. They returned to full competition at 18 months after the surgery.

Discussion

The actual mechanism of indirect patellar tendon rupture is a strong contraction of the quadriceps with sudden flexion of the knee [26] or hyperflexion of knee with excessive loading in sports activities such as soccer and basketball [11]. However, weight lifting is known to be commonly associated with an increase in knee injury risk [21, 22]. In weight lifting, the act consists of two lifts. One is the snatch and the other is to clean and jerk. The injuries that occur to the knees are usually the result of many factors, which include the biomechanical impact of the lifts themselves. The condition of the patella tendon can be impacted by the excessive and repetitive contraction of the quadriceps causing microscopic tears. This repeated stress and loading also suppress the healing process leading to inflammation, pain and dysfunction. One of the palliative measures preferred by Taiwanese weight lifters is local injections of steroids. The result of this therapy quickly enables the athletes to continue their training schedule as well as finish their competitions. They are often unaware of the deleterious effects of the accumulation of steroid injections.

Although the role of steroid injection in tendon rupture is still controversial, local injections of corticosteroids have been implicated as one of the etiologic factors for tendon rupture [2, 3, 6, 16, 19, 27, 31]. In animal studies, steroid injections leading to pathologic tendon degeneration had been identified in endurance-trained mice [17, 18]. In in vitro studies, the glucosteroid suppresses the proteoglycan production [31], proliferation [24] and migration [28] of human tendon cell, which may impair tendon-healing and lead to spontaneous tendon rupture. The majority of tendon ruptures occurs just a few days to 6 weeks after the injections [20, 29]. The location of the rupture occurs at the point of origin on the patellar tendon and its insertion on the tibia tuberosity, when the quadriceps muscle suddenly contracts. This type of patellar tendon rupture is reported to be associated with athletic activity such as “jumper’s knee” [7, 11].

In this investigation, all the seven weight lifters had history of knee pain and were treated as having patellar tendinopathy. They all had previous corticosteroid injections at the region of the patella tendon on at least five different occasions within 1 year prior to their recent injury and rupture. Except for the use of steroids, none had systemic predisposing factors for tendon rupture. Physical examination reveals a defect in the patellar tendon (Fig. 1a) and it may rest more proximally than normal (Fig. 1b). The presence of a “patella alta” on lateral radiographs suggests the rupture of the tendon. As noted before, a simple physical examination can determine the diagnosis. Prompt surgical repair is necessary to help the patients to regain their normal activities especially in active athletes. At the time of follow-up, five athletes who were graded with excellent outcome could reach the level better than the level before injury without any discomfort. Two athletes who were graded with good outcome could reach the level before injury, and they complained mild discomfort of the injured knee after finishing the competition. A mean loss of 8% in knee extension strength may remain as long as 2 years after the incidence. The limitations of the case series included its retrospective nature and the small number of patella tendon ruptures caused by local steroid injections in weight lifters who required surgical repair. Additionally, the limited follow-up time is another weakness in this study. A larger sample size and longer follow-up duration study would help to understand the further competition ability and the incidence of patellar tendon rerupture in the weight lifters who continue the competition activities after repairing the ruptured patellar tendon caused by local steroid injections.

Conclusion

For physicians who treat patellar tendonitis, especially in weight lifters, it is important to recognize the contributing factors for tendon rupture, especially in those who have had steroid injections. It is advisable to minimize the dosage and frequency of steroid injections to avoid the possibility of further complications. In addition, it is imperative to protect the sound site after injection. Lastly, it is important that surgical repair of a torn patellar tendon should be performed as soon as possible along with intensive supervised rehabilitation. If normal length and strength of the tendon can be maintained, functional restoration will be excellent.

References

Balasubramaniam P, Prathap K (1972) The effect of injection of hydrocortisone into rabbit calcaneal tendons. J Bone Joint Surg Br 54:729–734

Bickel KD (1996) Flexor pollicis longus tendon rupture after corticosteroid injection. J Hand Surg Am 21:152–153

Bjorkman A, Jorgsholm P (2004) Rupture of the extensor pollicis longus tendon: a study of aetiological factors. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 38:32–35

Bonamo JJ, Krinick RM, Sporn AA (1984) Rupture of the patellar ligament after use of its central third for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 66:1294–1297

Carson WG Jr (1985) Diagnosis of extensor mechanism disorders. Clin Sports Med 4:231–246

Fredberg U (1997) Local corticosteroid injection in sport: review of literature and guidelines for treatment. Scand J Med Sci Sports 7:131–139

Giblin P, Small A, Nichol R (1982) Bilateral rupture of the ligamentum patellae: two case reports and a review of the literature. Aust N Z J Surg 52:145–148

Insall J, Salvati E (1971) Patella position in the normal knee joint. Radiology 101:101–104

Karlsson J, Lundin O, Lossing IW, Peterson L (1991) Partial rupture of the patellar ligament—results after operative treatment. Am J Sports Med 19:403–408

Karpman RR, McComb JE, Volz RG (1980) Tendon rupture following local steroid injection: report of four cases. Postgrad Med 68:169–174

Kelly DW, Carter VW, Jobe FW, Kerlan RK (1984) Patellar and quadriceps tendon ruptures—jumper’s knee. Am J Sports Med 12:375–374

Lindy PB, Boynton MB, Fadale PD (1994) Repair of patellar tendon disruptions without hardware. J Orthop Trauma 9:238–243

Linke E (1975) Achilles tendon ruptures following direct cortisone injection. Hefte Unfallheilkd 121:302–303

Lysholm J, Gillquist J (1982) Evaluation of knee ligament surgery results with special emphasis on use of a scoring scale. Am J Sports Med 10:150–154

Mackie JW, Goldin B, Foss ML, Cockrell JL (1974) Mechanical properties of rabbit tendons after repeated anti-inflammatory steroid injections. Med Sci Sports 6:198–202

Meier JO (1990) Rupture of biceps tendon after injection of steroid. Ugeskr Laeger 152:3258

Michna H (1988) Appearance and ultrastructure of intranuclear crystalloids in tendon fibroblasts induced by an anabolic steroid hormone in the mouse. Acta Anat 133:247–250

Michna H (1987) Tendon injuries induced by exercise and anabolic steroids in experimental mice. Int Orthop 11:157–162

Paavola M, Kannus P, Jarvinen TA, Jarvinen TL, Jozsa L, Jarvinen M (2002) Treatment of tendon disorders. Is there a role for corticosteroid injection? Foot Ankle Clin 7:501–513

Phelps D, Sonstegard DA, Matthews LS (1974) Corticosteroid injection effects on the biomechanical properties of rabbit patellar tendons. Clin Orthop Relat Res 100:345–348

Risser WL (1990) Musculoskeletal injuries caused by weight training. Guidelines for prevention. Clin Pediatr 29:305–310

Risser WL, Risser JM, Preston D (1990) Weight-training injuries in adolescents. Am J Dis Child 144:1015–1017

Rosenberg JM, Whitaker JH (1991) Bilateral infrapatellar tendon rupture in a patient with jumpers knee. Am J Sports Med 19:94–95

Scutt N, Rolf CG, Scutt A (2006) Glucocorticoids inhibit tenocyte proliferation and Tendon progenitor cell recruitment. J Orthop Res 24:173–182

Siwek CW, Rao JU (1981) Ruptures of the extensor mechanism of the knee joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 64:932–937

Sochart DH, Shravat BP (1994) Bilateral patellar tendon disruption—a professional predisposition? J Accid Emerg Med 11:255–256

Sweetnam R (1969) Corticosteroid arthropathy and tendon rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Br 51:397–398

Tsai WC, Tang FT, Wong MK, Pang JH (2003) Inhibition of tendon cell migration by dexamethasone is correlated with reduced alpha-smooth muscle actin gene expression: a potential mechanism of delayed tendon healing. J Orthop Res 21:265–271

Unverferth LJ, Olix ML (1973) The effect of local steroid injections on tendon. J Sports Med 1:31–37

Webb LX, Toby EB (1986) Bilateral rupture of the patellar tendon in an otherwise healthy male patient following minor trauma. J Trauma 26:1045–1048

Wong MW, Tang YN, Fu SC, Lee KM, Chan KM (2004) Triamcinolone suppresses human tenocyte cellular activity and collagen synthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 421:277–281

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, SK., Lu, CC., Chou, PH. et al. Patellar tendon ruptures in weight lifters after local steroid injections. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 129, 369–372 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-008-0655-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-008-0655-1