Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is associated with a substantial risk of thromboembolism and mortality, significantly reduced by oral anticoagulation. Adherence to guidelines may lower the risks for both all cause and cardiovascular (CV) deaths.

Methods

Our objective was to evaluate if antithrombotic prophylaxis according to the 2012 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines is associated to a lower rate of adverse outcomes. Data were obtained from REPOSI; a prospective observational study enrolling inpatients aged ≥65 years. Patients enrolled in 2012 and 2014 discharged with an AF diagnosis were analysed.

Results

Among 2535 patients, 558 (22.0 %) were discharged with a diagnosis of AF. Based on ESC guidelines, 40.9 % of patients were on guideline-adherent thromboprophylaxis, 6.8 % were overtreated, and 52.3 % were undertreated. Logistic analysis showed that increasing age (p = 0.01), heart failure (p = 0.04), coronary artery disease (p = 0.013), peripheral arterial disease (p = 0.03) and concomitant cancer (p = 0.003) were associated with non-adherence to guidelines. Specifically, undertreatment was significantly associated with increasing age (p = 0.001) and cancer (p < 0.001), and inversely associated with HF (p = 0.023). AF patients who were guideline adherent had a lower rate of both all-cause death (p = 0.007) and CV death (p = 0.024) compared to those non-adherent. Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that guideline-adherent patients had a lower cumulative risk for both all-cause (p = 0.002) and CV deaths (p = 0.011). On Cox regression analysis, guideline adherence was independently associated with a lower risk of all-cause and CV deaths (p = 0.019 and p = 0.006).

Conclusions

Non-adherence to guidelines is highly prevalent among elderly AF patients, despite guideline-adherent treatment being independently associated with lower risk of all-cause and CV deaths. Efforts to improve guideline adherence would lead to better outcomes for elderly AF patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AF) have progressively increased over the last 20 years, especially in the elderly [1, 2]. In patients aged ≥65 years, the prevalence of AF has more than doubled from 1993 to 2007 [1]. Because many patients are asymptomatic, guidelines now recommend screening for AF in all subjects age 65 and over [3].

AF is associated with an increased risk for both thromboembolic events and mortality, whether all-cause or from cardiovascular (CV) causes [1, 4]. Oral anticoagulant (OAC) therapy significantly reduces the risk of thromboembolism and mortality amongst AF patients [4]. Both OAC persistence and good quality anticoagulation control reduce major adverse events among AF patients [5–8].

Nonetheless, physician attitudes towards prescribing OAC and their adherence to guidelines vary [9]. Recent data from the EURObservational Research Programme AF (EORP-AF) Pilot Registry reported that up to 40 % of patients managed by European cardiologists are non-adherent to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines, and that both undertreatment and overtreatment were associated with worst outcomes [10]. Elderly patients seem to be less likely to be treated with OAC, due to their perceived frailty and higher risk of bleeding [11]. When properly prescribed, OAC thromboprophylaxis using a vitamin K antagonist (VKA, e.g., warfarin) with good anticoagulation control is associated with better outcomes, even amongst the elderly [11, 12].

The aims of this study were as follows: (1) to assess physician adherence to guidelines in a cohort of Italian AF elderly patients admitted acutely to internal medicine and geriatric wards; (2) to describe the main factors associated with guideline non-adherence; and (3) to evaluate the risk of all-cause and CV deaths according to adherence or non-adherence to guidelines.

Methods

We studied an elderly AF population from the REPOSI (REgistro POliterapie SIMI) study [13]. The latter is a multicentre collaborative observational registry jointly held by the Italian Society of Internal Medicine (SIMI), the Ca’ Granda Maggiore Policlinico Hospital Foundation, and the Mario Negri Institute of Pharmacological Research and based on a network of both internal medicine and geriatric wards in Italy and Spain. Full details on the study design and specific aims have been reported [13].

Briefly, REPOSI was held for four non-consecutive years: 2008, 2010, 2012, and 2014. In each of those years over a period of 4 weeks, quarterly (i.e., February, June, September, and December), consecutive patients admitted to the participating wards aged more than 65 years were enrolled. For the present study, only patients enrolled in the 2012 and 2014 study cohorts were considered, as data recorded were more comprehensive than those initially collected in 2008 and 2010. The study protocol was first approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ca’ Granda Maggiore Policlinico Hospital Foundation, and then ratified for every enrolling site by local Ethics Committee. The study was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice recommendations and the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients were selected according to the International Classification of Diseases—9th Edition (ICD-9) system. For the purposes of this analysis, all patients discharged with the 427.31 ICD-9 code, corresponding to AF diagnosis, were considered.

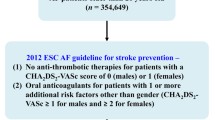

Thromboembolic risk was defined according to the CHA2DS2-VASc score [4] that defines ‘Low risk’ patients males with a CHA2DS2-VASc 0 or females with a CHA2DS2-VASc equal to 1; ‘moderate risk’, male patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score 1; and ‘high risk’, all patients with CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥2 [4]. Given the inclusion criteria (i.e., age ≥65), no patients with low risk were included in this analysis.

Guideline adherence was defined according to ESC 2012 Guidelines [3]. AF patients at moderate or high risk treated with OAC alone were considered as guideline adherent. Undertreatment was defined for patients at moderate or high risk not treated with any OAC or treated with antiplatelet drugs (AP); conversely, overtreatment was considered for all patients, both with moderate or high risk, treated with OAC plus AP [3]. Medication use was assessed according to the Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System. As reported in the Supplementary Materials, treatment with AP was defined according to ATC codes B01AC* and N02BA01, while treatment with OAC was defined according to ATC codes B01AA* and B01AE*.

Concomitant diagnoses were evaluated according to the ICD-9 codes, as reported in the Supplementary Materials. Interactions of comorbidities were evaluated by the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) severity index and comorbidity index [14, 15]. Polypharmacy was defined for the contemporary use of 5 or more drugs [13]. Cognitive status was evaluated with the short blessed test [16]; elderly depression was investigated with the Geriatric Depression Scale [17]. Functional status was assessed with the Barthel index [18].

Follow-up data were collected at 3 and 12 months after discharge through telephone interview or, if patients were not alive, data were collected from the next of kin. According to death causes reported into the electronic case report form, based on investigator judgement, a CV death was defined when it was related to any cardiac or vascular reason. Both all-cause and CV deaths were considered as study outcomes.

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables were tested for normality with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Variables with normal distribution were expressed as means and standard deviations (SD), and tested for differences with the Student t test. Non-normal variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) and differences tested with the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables, expressed as counts and percentages, were analysed by a Chi-square test.

A regression analysis was performed to establish clinical factors significantly associated with guideline non-adherence, undertreatment, or overtreatment. All variables with a p < 0.10 in the comparison between the two groups at the baseline were included in a univariate analysis, and those univariate predictors with a statistical significance of less than 10 % were included into a forward multivariate logistic model.

A logistic regression analysis was also performed (adjusted for CIRS severity index, CIRS comorbidity index, and thromboembolic risk) to establish the association between undertreatment and study outcomes. This analysis was not performed for the overtreatment group, given the very small number of events recorded in this group.

A survival analysis was performed both according to parametric and semi-parametric methods, comparing guideline adherence or non-adherence. A log-rank test was performed to establish whether or not there was a difference in survival between the two groups. Kaplan-Meier curves were also plotted. A Cox regression analysis adjusted for CIRS severity index, CIRS comorbidity index, and thromboembolic risk was also performed. A two-sided p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS v. 22.0 (IBM, NY, USA).

Results

Of the 2535 patients enrolled in the 2012 and 2014 cohorts, 558 (22.0 %) were discharged with a diagnosis of AF [median (IQR) age 82 (76–90) years, 297 (53.2 %) females]. Amongst AF patients, hypertension was the most common risk factor (n = 471, 84.4 %) [Table 1]. Median (IQR) CHA2DS2-VASc score was 4 [3–5], with 554 patients (99.3 %) being at high thromboembolic risk.

Antithrombotic prophylaxis amongst patients at high thromboembolic risk is shown in Fig. 1. Among those, only 41.0 % were treated with OAC, while 6.7 % were treated with OAC plus AP. Of those treated with OAC, 222 out of 227 (97.8 %) patients were treated with a VKA and only 5 (2.2 %) with a non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant (NOAC); all patients treated with OAC plus AP used a VKA.

Based on the 2012 ESC guidelines, only 40.9 % (n = 228) of the patients were guideline adherent, while 52.3 % (n = 292) were undertreated and 38 (6.8 %) were overtreated. Baseline characteristics according to guideline-adherence or non-adherence status are in Table 1. Guidelines-adherent patients were younger (p = 0.005) and had a lower CIRS severity index (p = 0.046). Guideline-adherent patients also had more HF (p = 0.014) but less CAD (p = 0.005), PAD (p = 0.009), and cancer (p = 0.002). Functional status indexes were similar in both groups.

Associations with guideline adherence and non-adherence

Multivariable logistic analysis showed that age [odds ratio (OR) 1.03 per year, 95 % confidence interval 1.01–1.06, and p = 0.01], concomitant diagnoses of CAD (OR 1.71, 95 % CI 1.12–2.61, and p = 0.04), PAD (OR 5.25, 95 % CI 1.18–23.41, and p = 0.03), and cancer (OR 2.31, 95 % CI 0.47–0.98, and p = 0.03) were significantly associated with guideline non-adherence. Concomitant diagnosis of HF (OR 0.68, 95 % CI 0.47–0.98, and p = 0.04) was inversely associated with guideline non-adherence.

Undertreatment was significantly associated with increasing age (p = 0.001) and concomitant diagnosis of cancer (p < 0.001) and inversely associated with HF (p = 0.023) (Table 2). Increasing age (p = 0.036), female sex (p = 0.023), and COPD diagnosis (p = 0.007) were inversely associated with overtreatment (Table 2). A clinical history of CAD (p < 0.001), PAD (p = 0.015), and stroke/TIA (p = 0.004) was positively associated with overtreatment (Table 2).

Survival analysis

In the overall cohort, follow-up data for at least one follow-up time point were available in 74.6 % patients (n = 416). No major differences were found when compared with lost at follow-up patients, except for CIRS severity index and alcohol consumption that were lower in patients lost to follow-up (see Table S1 in Supplementary Materials).

Median (IQR) follow-up time was 115 (98–371) days. A total of 73 (13.1 %) all-cause deaths and 27 (4.8 %) CV deaths were recorded. Guideline non-adherent patients had higher rates for all-cause (8.9 vs. 3.4 %, p = 0.007 vs. guideline adherent) and CV death (21.9 vs. 11.7 %, p = 0.024 vs. guideline adherent). No significant difference was detected in rates of non-CV death (13.1 vs. 8.4 % for guideline non-adherent vs. adherent patients; p = 0.130). Undertreatment was significantly associated with all-cause deaths (OR 2.30, 95 % CI 1.32–4.02, and p = 0.003) and CV deaths (OR 2.88, 95 % CI 1.13–7.39, and p = 0.027). This association remained statistically significant even after adjustment for CIRS severity index, CIRS comorbidity index, and thromboembolic risk (OR 2.78, 95 % CI 1.07–7.23, and p = 0.036, and OR 2.12, 95 % CI 1.21–3.72, and p = 0.009, respectively).

Kaplan–Meier curves showed that guideline-adherent patients had a lower cumulative risk for both all-cause deaths (Log-Rank 9.631 and p = 0.002) and CV deaths (Log-Rank 6.497 and p = 0.011) compared to guideline non-adherent patients (Fig. 2). Cox regression analysis showed that guideline-adherent patients had a lower risk for all-cause death (HR 0.47, 95 % CI 0.29–0.81, and p = 0.006) and CV death [hazard ratio (HR) 0.33, 95 % CI 0.13–0.83, and p = 0.019), after adjustment for CIRS severity index, CIRS comorbidity index, and thromboembolic risk.

Discussion

The principal findings of this study are that first, almost 60 % of Italian elderly patients with AF were managed with a guideline non-adherent approach for OAC, with most being undertreated (52.3 %). Second, the main clinical factors associated with guideline non-adherence were older age and a clinical history of HF, CAD, and PAD, as well as the concomitant diagnosis of cancer. In particular, increasing age was associated with undertreatment, along with the diagnosis of cancer, while HF was inversely associated with undertreatment. Conversely, a younger age, female sex, and a previous history of CAD, PAD, and stroke/TIA were associated with overtreatment with concomitant OAC and AP. Third, undertreatment was associated with a significant risk for both all-cause and CV deaths, moreover guideline-adherent AF patients had a lower risk for both endpoints.

In this study, the percentage of AF patients treated with a guideline-adherent approach was lower than in the previous reports [10, 19]. More recently, the EURObservational Research Programme AF (EORP-AF) Pilot Phase reported that, based on the 2012 ESC guidelines, AF patients were guideline-adherent in 60.6 %. The EORP-AF reflected patient management by European cardiologists from both in- and outpatient settings, while in the REPOSI study, all the in-patients enrolled were elderly and from internal medicine or geriatric wards.

In the EORP-AF ancillary analysis on guidelines adherence, the South European region (which included Italy) was associated with undertreatment, confirming several previous reports of a significantly lower rate of patients treated with OAC among Italian AF patients [20–24]. This seems to occur despite several reports on effectiveness and safety, showing that elderly patients treated with a VKA had a significant benefit in reducing both thromboembolic events and mortality, irrespective of age [12]. A recent position paper from the ESC Working Group on Thrombosis also stated that while elderly patients were under-represented in various clinical trials investigating antithrombotic drugs; OAC treatment with VKA or NOACs was effective and safe in elderly patients [25]. The BALKAN-AF survey also reported that age was inversely associated with OAC prescription, but it was positively associated with undertreatment with AP [26].

Age and the concomitant diagnosis of cancer were clinical factors associated with guideline non-adherence in this study, while clinical history of HF was inversely associated with guideline non-adherence, at variance with the previous reports, such as the EORP-AF registry [10]. Specifically, both age and malignancy were significantly associated with undertreatment in REPOSI, while only malignancy was associated with undertreatment in the EORP-AF cohort [10]. This perhaps suggests that frailty in elderly patient influences physician decision for non-treatment with OAC. Similar observations were made in the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF), where frailty was reported in a large proportion of patients as the main contraindication for OAC prescription [27]. Furthermore, similar findings were reported in a recent observational Canadian study in the setting of octogenarian AF patients [28]. In the REPOSI cohort, we found no significant difference in functional status indexes (i.e., Barthel index) between patients treated with a guideline-adherent approach and those who were non-guideline adherent.

When investigating factors significantly associated with overtreatment, most AF patients with CAD, PAD, and Stroke/TIA were overtreated with OAC and AP. Similar findings were also reported in the EORP-AF [10] and the BALKAN-AF surveys [26]. This approach seems to be maintained widely by physicians despite explicit guideline recommendations to only prescribe OAC for stroke prevention in AF patients with stable vascular disease [3, 29].

Our results emphasise the importance of OAC for AF patients in reducing all-cause mortality and CV, even in the elderly. Physician adherence to guidelines in terms of OAC use represents an important clinical step. In the Euro Heart Survey, undertreatment was significantly associated with thrombosis-related events, with a twofold higher risk compared to a guideline-adherent approach [19]. Conversely, undertreatment was associated with an increase in the composite outcome of any thromboembolic event, major bleeding, and CV death [19]. The analysis from 1-year follow-up of the EORP-AF study also confirmed that both undertreatment and overtreatment are associated with higher risk for the composite endpoint of all-cause death plus any thromboembolic event, with a more than 60 % higher risk for both undertreatment and overtreatment [10]. Indeed, undertreatment per se was associated with a higher risk for any thromboembolic event (OR 1.72) [10]. Of note, our results provide a “real world” validation for the degree of implementation of the ESC guidelines in a large unselected population of elderly AF patients. Given that many elderly (or very elderly) patients are excluded or under-represented in randomized clinical trials specifically evaluating OAC therapy (as discussed above), our data strengthen and underscore the necessity for large prospective studies in the elderly AF population.

Limitations

The main limitation of the study is its observational nature, with relatively limited power to detect differences in survival. Lack of follow-up data for some of our patients represents another important limitation, and no precise details about the cause(s) of death were obtained. We could not evaluate how effective anticoagulation could impact on outcomes occurrence given the absence in the registry dataset of any index of anticoagulation control (e.g., time in therapeutic range, TTR). Furthermore, the evaluation of OAC therapy adequacy based solely on the thromboembolic risk assessment may not be comprehensive enough. Possible contraindications to OAC therapy, as well as possible comorbidities interacting with OAC (i.e., chronic kidney disease), must be taken into account during the prescription process. Finally, given the low number of the subgroups considered, our results should be interpreted cautiously.

Conclusions

Guideline non-adherence was evident for a large proportion of elderly patients with AF. Guideline-adherent treatment was independently associated with a significantly lower risk of all-cause and CV deaths. Efforts to improve guideline adherence would lead to better outcomes for elderly AF patients.

References

Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS et al (2015) Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 133:e38–e360. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350

Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA et al (2001) Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA 285:2370–2375. doi:10.1001/jama.285.18.2370

Camm AJ, Lip GYH, De Caterina R et al (2012) 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J 33:2719–2747. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253

Lip GYH, Lane DA (2015) Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. JAMA 313:1950–1962. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.4369

Kirchhof P, Breithardt G, Bax J et al. (2015) A roadmap to improve the quality of atrial fibrillation management: proceedings from the fifth Atrial Fibrillation Network/European Heart Rhythm Association consensus conference. Europace 18:37–50. doi:10.1093/europace/euv304

Wan Y, Heneghan C, Perera R et al (2008) Anticoagulation control and prediction of adverse events in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 1:84–91. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.796185

Gallagher AM, Setakis E, Plumb JM et al (2011) Risks of stroke and mortality associated with suboptimal anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation patients. Thromb Haemost 106:968–977. doi:10.1160/TH11-05-0353

De Caterina R, Husted S, Wallentin L et al (2013) Vitamin K antagonists in heart disease: current status and perspectives (Section III). Thromb Haemost 110:1087–1107. doi:10.1160/TH13-06-0443

Pugh D, Pugh J, Mead GE (2011) Attitudes of physicians regarding anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Age Ageing 40:675–683. doi:10.1093/ageing/afr097

Lip GYH, Laroche C, Popescu MI et al (2015) Improved outcomes with European Society of Cardiology guideline-adherent antithrombotic treatment in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the EORP-AF General Pilot Registry. Europace. doi:10.1093/europace/euv269

Marinigh R, Lip GYH, Fiotti N et al (2010) Age as a risk factor for stroke in atrial fibrillation patients: implications for thromboprophylaxis. J Am Coll Cardiol 56:827–837. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.028

Lip GYH, Clementy N, Pericart L et al (2014) Stroke and major bleeding risk in elderly patients aged ≥75 years with atrial fibrillation: the Loire Valley atrial fibrillation project. Stroke 46:143–150. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007199

Nobili A, Licata G, Salerno F et al (2011) Polypharmacy, length of hospital stay, and in-hospital mortality among elderly patients in internal medicine wards. The REPOSI study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 67:507–519. doi:10.1007/s00228-010-0977-0

Miller MD, Towers A (1991) A manual of guidelines for scoring the cumulative illness rating scale for geriatrics (CIRS-G). University of Pittsburg, Pittsburg, PA

Salvi F, Miller MD, Grilli A et al (2008) A manual of guidelines to score the modified cumulative illness rating scale and its validation in acute hospitalized elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 56:1926–1931. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01935.x

Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P et al (1983) Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry 140:734–739. doi:10.1176/ajp.140.6.734

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL et al (1982) Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 17:37–49

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW (1965) Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Md State Med J 14:61–65

Nieuwlaat R, Olsson SB, Lip GYH et al (2007) Guideline-adherent antithrombotic treatment is associated with improved outcomes compared with undertreatment in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation. The Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Am Heart J 153:1006–1012. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.008

Raparelli V, Proietti M, Buttà C et al (2014) Medication prescription and adherence disparities in non valvular atrial fibrillation patients: an Italian portrait from the ARAPACIS study. Intern Emerg Med 9:861–870. doi:10.1007/s11739-014-1096-1

Di Pasquale G, Mathieu G, Pietro Maggioni A et al (2013) Current presentation and management of 7148 patients with atrial fibrillation in cardiology and internal medicine hospital centers: the ATA AF study. Int J Cardiol 167:2895–2903. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.07.019

Marcucci M, Iorio A, Nobili A et al (2010) Factors affecting adherence to guidelines for antithrombotic therapy in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation admitted to internal medicine wards. Eur J Intern Med 21:516–523. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2010.07.014

Gussoni G, Di Pasquale G, Vescovo G et al (2013) Decision making for oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: the ATA-AF study. Eur J Intern Med 24:324–332. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2013.04.008

Campanini M, Frediani R, Artom A et al (2013) Real-world management of atrial fibrillation in Internal Medicine units: the FADOI “FALP” observational study. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 14:26–34. doi:10.2459/JCM.0b013e328348e5ce

Andreotti F, Rocca B, Husted S et al (2015) Antithrombotic therapy in the elderly: expert position paper of the European society of cardiology working group on thrombosis. Eur Heart J 36:3238–3249. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv304

Potpara TS, Dan G-A, Trendafilova E et al (2016) Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation and “real world” adherence to guidelines in the Balkan Region: the BALKAN-AF Survey. Sci Rep 6:20432. doi:10.1038/srep20432

O’Brien EC, Holmes DN, Ansell JE et al (2014) Physician practices regarding contraindications to oral anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation: findings from the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF) registry. Am Heart J 167(601–609):e1. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.12.014

Lefebvre MCD, St-Onge M, Glazer-Cavanagh M et al (2015) The effect of bleeding risk and frailty status on anticoagulation patterns in octogenarians with atrial fibrillation: the FRAIL-AF study. Can J Cardiol 32:169–176. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2015.05.012

Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GYH et al (2010) Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 31:2369–2429. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278

Acknowledgments

REPOSI study was Supported by the Italian Society of Internal Medicine (SIMI), the Ca’ Granda Maggiore Policlinico Hospital Foundation and the Mario Negri Institute of Pharmacological Research. This study was Supported by an unrestricted grant from Pfizer to the Scientific Direction of Ca’ Granda Maggiore Policlinico Hospital Foundation.

REPOSI ( RE gistro PO literapie SI MI, Società Italiana di Medicina Interna) Investigators Steering Committee Pier Mannuccio Mannucci (Chair, Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano), Alessandro Nobili (co-chair, IRCCS-Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche “Mario Negri”, Milano), Mauro Tettamanti, Luca Pasina, Carlotta Franchi (IRCCS-Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche “Mario Negri”, Milano), Francesco Perticone (Presidente SIMI), Francesco Salerno (IRCCS Policlinico San Donato Milanese, Milano), Salvatore Corrao (ARNAS Civico, Di Cristina, Benfratelli, DiBiMIS, Università di Palermo, Palermo), Alessandra Marengoni (Spedali Civili di Brescia, Brescia), Giuseppe Licata (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico P. Giaccone di Palermo, Palermo, Medicina Interna e Cardioangiologia), Francesco Violi (Policlinico Umberto I, Roma, Prima Clinica Medica), Gino Roberto Corazza, (Reparto 11, IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo di Pavia, Pavia, Clinica Medica I), Maura Marcucci (Unità di Geriatria, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico & Dipartimento di Scienze Cliniche e di Comunità, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milano, Italia).

Clinical Data Monitoring and Revision Tarek Kamal Eldin, Maria Pia Donatella Di Blanca (IRCCS-Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche “Mario Negri”, Milano).

Database Management and Statistics Mauro Tettamanti, Codjo Djignefa Djade, Ilaria Ardoino, Laura Cortesi (IRCCS-Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche “Mario Negri”, Milano).

Investigators

Italian Hospitals Domenico Prisco, Elena Silvestri, Caterina Cenci, Giacomo Emmi (Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Careggi Firenze, Medicina Interna Interdisciplinare); Gianni Biolo, Gianfranco Guarnieri, Michela Zanetti, Giovanni Fernandes (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Ospedali Riuniti di Trieste, Trieste, Clinica Medica Generale e Terapia Medica); Massimo Vanoli, Giulia Grignani, Gianluca Casella, (Azienda Ospedaliera della Provincia di Lecco, Ospedale di Merate, Lecco, Medicina Interna); Mauro Bernardi, Silvia Li Bassi, Luca Santi, Giacomo Zaccherini (Azienda Ospedaliera Policlinico Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Semeiotica Medica Bernardi); Elmo Mannarino, Graziana Lupattelli, Vanessa Bianconi, Francesco Paciullo (Azienda Ospedaliera Santa Maria della Misericordia, Perugia, Medicina Interna, Angiologia, Malattie da Arteriosclerosi); Ranuccio Nuti, Roberto Valenti, Martina Ruvio, Silvia Cappelli, Alberto Palazzuoli (Azienda Ospedaliera Università Senese, Siena, Medicina Interna I); Teresa Salvatore, Ferdinando Carlo Sasso (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria della Seconda Università degli Studi di Napoli, Napoli, Medicina Interna e Malattie Epato-Bilio Metaboliche Avanzate); Domenico Girelli, Oliviero Olivieri, Thomas Matteazzi (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata di Verona, Verona, Medicina Generale a indirizzo Immuno-Ematologico e Emocoagulativo); Mario Barbagallo, Lidia Plances, Roberta Alcamo (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico Giaccone Policlinico di Palermo, Palermo, Unità Operativa di Geriatria e Lungodegenza); Giuseppe Licata, Luigi Calvo, Maria Valenti (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico P. Giaccone di Palermo, Palermo, Medicina Interna e Cardioangiologia); Marco Zoli, Raffaella Arnò (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico S. Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Unità Operativa di Medicina Interna Zoli); Franco Laghi Pasini, Pier Leopoldo Capecchi, Maurizio Bicchi (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese, Siena, Unità Operativa Complessa Medicina 2); Giuseppe Palasciano, Maria Ester Modeo, Maria Peragine, Fabrizio Pappagallo, Stefania Pugliese, Carla Di Gennaro (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Consorziale Policlinico di Bari, Bari, Medicina Interna Ospedaliera “L. D’Agostino”, Medicina Interna Universitaria “A. Murri”); Alfredo Postiglione, Maria Rosaria Barbella, Francesco De Stefano (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico Federico II di Napoli, Medicina Geriatrica Dipartimento di Clinica Medica); Maria Domenica Cappellini, Giovanna Fabio, Sonia Seghezzi, Margherita Migone De Amicis (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Unità Operativa Medicina Interna IA); Daniela Mari, Paolo Dionigi Rossi, Sarah Damanti, Barbara Brignolo Ottolini, Sarah Damanti (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Geriatria); Gino Roberto Corazza, Emanuela Miceli, Marco Vincenzo Lenti, Donatella Padula (Reparto 11, IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo di Pavia, Pavia, Clinica Medica I); Giovanni Murialdo, Alessio Marra, Federico Cattaneo (IRCS Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria San Martino-IST di Genova, Genova, Clinica di Medicina Interna 2); Maria Beatrice Secchi, Davide Ghelfi (Ospedale Bassini di Cinisello Balsamo, Milano, Divisione Medicina); Luigi Anastasio, Lucia Sofia, Maria Carbone (Ospedale Civile Jazzolino di Vibo Valentia, Vibo Valentia, Medicina interna); Giovanni Davì, Maria Teresa Guagnano, Simona Sestili (Ospedale Clinicizzato SS. Annunziata, Chieti, Clinica Medica); Gerardo Mancuso, Daniela Calipari, Mosè Bartone (Ospedale Giovanni Paolo II Lamezia Terme, Catanzaro, Unità Operativa Complessa Medicina Interna); Maria Rachele Meroni (Ospedale Luigi Sacco, Milano, Medicina 3); Paolo Cavallo Perin, Bartolomeo Lorenzati, Gabriella Gruden, Graziella Bruno, Cristina Amione, Paolo Fornengo (Dipartimento di Scienze Mediche, Università di Torino, Città della Scienza e della Salute, Torino, Medicina 3); Rodolfo Tassara, Deborah Melis, Lara Rebella (Ospedale San Paolo, Savona, Medicina I); Giuseppe Delitala, Vincenzo Pretti, Maristella Salvatora Masala (Ospedale Universitario Policlinico di Sassari, Sassari, Clinica Medica); Luigi Bolondi, Leonardo Rasciti, Ilaria Serio (Policlinico Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Unità Operativa Complessa Medicina Interna); Filippo Rossi Fanelli, Antonio Amoroso, Alessio Molfino, Enrico Petrillo (Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza Università di Roma, Roma, Medicina Interna H); Giuseppe Zuccalà, Francesco Franceschi, Guido De Marco, Cordischi Chiara, Sabbatini Marta (Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, Roma, Roma, Unità Operativa Complessa Medicina d’Urgenza e Pronto Soccorso)Giuseppe Romanelli, Claudia Amolini, Deborah Chiesa, Alessandra Marengoni (Spedali Civili di Brescia, Brescia, Geriatria); Antonio Picardi, Umberto Vespasiani Gentilucci, Paolo Gallo (Università Campus Bio-Medico, Roma, Medicina Clinica-Epatologia); Giorgio Annoni, Maurizio Corsi, Sara Zazzetta, Giuseppe Bellelli (Università degli studi di Milano-Bicocca Ospedale S. Gerardo, Monza, Unità Operativa di Geriatria); Franco Arturi, Elena Succurro, Mariangela Rubino, Giorgio Sesti (Università degli Studi Magna Grecia, Policlinico Mater Domini, Catanzaro, Unità Operativa Complessa di Medicina Interna); Paola Loria, Maria Angela Becchi, Gianfranco Martucci, Alessandra Fantuzzi, Mauro Maurantonio (Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Medicina Metabolica-NOCSAE, Baggiovara, Modena); Giuseppe Delitala, Stefano Carta, Sebastiana Atzori (Azienda Mista Ospedaliera Universitaria, Sassari, Clinica Medica); Maria Grazia Serra, Maria Antonietta Bleve (Azienda Ospedaliera “Cardinale Panico” Tricase, Lecce, Unità Operativa Complessa Medicina); Laura Gasbarrone, Maria Rosaria Sajeva (Azienda Ospedaliera Ospedale San Camillo Forlanini, Roma, Medicina Interna 1); Antonio Brucato, Silvia Ghidoni, Paola Di Corato (Azienda Ospedaliera Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo, Medicina 1); Giancarlo Agnelli, Emanuela Marchesini (Azienda Ospedaliera Santa Maria della Misericordia, Perugia, Medicina Interna e Cardiovascolare); Fabrizio Fabris, Michela Carlon, Francesca Turatto, Aldo Baritusso, Francesca Turatto (Azienda Ospedaliera Università di Padova, Padova, Clinica Medica I); Roberto Manfredini, Christian Molino, Marco Pala, Fabio Fabbian, Benedetta Boari, Alfredo De Giorgi (Azienda Ospedaliera, Universitaria Sant’Anna, Ferrara, Unità Operativa Clinica Medica); Giuseppe Paolisso, Maria Rosaria Rizzo, Maria Teresa Laieta (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria della Seconda Università degli Studi di Napoli, Napoli, VI Divisione di Medicina Interna e Malattie Nutrizionali dell’Invecchiamento); Giovanbattista Rini, Pasquale Mansueto, Ilenia Pepe (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico P. Giaccone di Palermo, Palermo, Medicina Interna e Malattie Metaboliche); Claudio Borghi, Enrico Strocchi, Valeria De Sando (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico S. Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Unità Operativa di Medicina Interna Borghi); Carlo Sabbà, Francesco Saverio Vella, Patrizia Suppressa, Raffaella Valerio (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Consorziale Policlinico di Bari, Bari, Medicina Interna Universitaria C. Frugoni); Stefania Pugliese, Caterina Capobianco (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Consorziale Policlinico di Bari, Bari, Clinica Medica I Augusto Murri); Luigi Fenoglio, Christian Bracco, Alessia Valentina Giraudo, Elisa Testa, Cristina Serraino (Azienda Sanitaria Ospedaliera Santa Croce e Carle di Cuneo, Cuneo, S. C. Medicina Interna); Silvia Fargion, Paola Bonara, Giulia Periti, Marianna Porzio (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Medicina Interna 1B); Flora Peyvandi, Alberto Tedeschi, Raffaella Rossio (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Medicina Interna 2); Valter Monzani, Valeria Savojardo, Christian Folli, Maria Magnini (Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Medicina Interna Alta Intensità di Cura); Francesco Salerno, Alessio Conca, Giulia Gobbo, Alessio Conca (IRCCS Policlinico San Donato e Università di Milano, San Donato Milanese, Medicina Interna); Carlo L. Balduini, Giampiera Bertolino, Stella Provini, Federica Quaglia (IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo di Pavia, Pavia, Clinica Medica III); Franco Dallegri, Luciano Ottonello, Luca Liberale (Università di Genova, Genova, Medicina Interna 1); Wu Sheng Chin, Laura Carassale, Silvia Caporotundo (Ospedale Bassini, Cinisello Balsamo, Milano, Unità Operativa di Geriatria); Giancarlo Traisci, Lucrezia De Feudis, Silvia Di Carlo (Ospedale Civile Santo Spirito di Pescara, Pescara, Medicina Interna 2); Nicola Lucio Liberato, Alberto Buratti, Tiziana Tognin (Azienda Ospedaliera della Provincia di Pavia, Ospedale di Casorate Primo, Pavia, Medicina Interna); Giovanni Battista Bianchi, Sabrina Giaquinto (Ospedale “SS Gerosa e Capitanio” di Lovere, Bergamo, Unità Operativa Complessa di Medicina Generale, Azienda Ospedaliera “Bolognini” di Seriate, Bergamo); Francesco Purrello, Antonino Di Pino, Salvatore Piro (Ospedale Garibaldi Nesima, Catania, Unità Operativa Complessa di Medicina Interna); Renzo Rozzini, Lina Falanga (Ospedale Poliambulanza, Brescia, Medicina Interna e Geriatria); Giuseppe Montrucchio, Elisabetta Greco, Pietro Tizzani, Paolo Petitti (Dipartimento di Scienze Mediche, Università di Torino, Città della Scienza e della Salute, Torino, Medicina Interna 2 U. Indirizzo d’Urgenza); Antonio Perciccante, Alessia Coralli (Ospedale San Giovanni-Decollato-Andisilla, Civita Castellana Medicina); Raffaella Salmi, Piergiorgio Gaudenzi, Susanna Gamberini (Azienda Ospedaliera-Universitaria S. Anna, Ferrara, Unità Operativa di Medicina Ospedaliera II); Andrea Semplicini, Lucia Gottardo (Ospedale SS. Giovanni e Paolo, Venezia, Medicina Interna 1); Gianluigi Vendemiale, Gaetano Serviddio, Roberta Forlano (Ospedali Riuniti di Foggia, Foggia, Medicina Interna Universitaria); Cesare Masala, Antonio Mammarella, Valeria Raparelli (Policlinico Umberto I, Roma, Medicina Interna D); Francesco Violi, Stefania Basili, Ludovica Perri (Policlinico Umberto I, Roma, Prima Clinica Medica); Raffaele Landolfi, Massimo Montalto, Antonio Mirijello, Carla Vallone (Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, Roma, Clinica Medica); Martino Bellusci, Donatella Setti, Filippo Pedrazzoli (Presidio Ospedaliero Alto Garda e Ledro, Ospedale di Arco, Trento, Unità Operativa di Medicina Interna Urgenza/Emergenza); Luigina Guasti, Luana Castiglioni, Andrea Maresca, Alessandro Squizzato, Marta Molaro (Università degli Studi dell’Insubria, Ospedale di Circolo e Fondazione Macchi, Varese, Medicina Interna I); Marco Bertolotti, Chiara Mussi, Maria Vittoria Libbra, Andrea Miceli, Elisa Pellegrini, Lucia Carulli (Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia, AUSL di Modena, Modena, Nuovo Ospedale Civile, Unità Operativa di Geriatria e U.O. di Medicina a indirizzo Metabolico Nutrizionistico); Francesco Perticone, Angela Sciacqua, Michele Quero, Chiara Bagnato (Università Magna Grecia Policlinico Mater Domini, Catanzaro, Unità Operativa Malattie Cardiovascolari Geriatriche); Roberto Corinaldesi, Roberto De Giorgio, Mauro Serra, Valentina Grasso, Eugenio Ruggeri (Dipartimento di Scienze Mediche e Chirurgiche, Unità Operativa di Medicina Interna, Università degli Studi di Bologna/Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria S.Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna); Andrea Salvi, Roberto Leonardi, Chiara Grassini, Ilenia Mascherona, Giorgio Minelli, Francesca Maltese (Spedali Civili di Brescia, U.O. 3a Medicina Generale); Armando Gabrielli, Massimo Mattioli, William Capeci, Giuseppe Pio Martino (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria, Ospedali Riuniti di Ancona, Clinica Medica); Salvatore Corrao, Silvia Messina (ARNAS Civico-Di Cristina-Benfratelli, Dipartimento Biomedico di Medicina Interna e Specialistica (Di.Bi.M.I.S.), Palermo); Riccardi Ghio, Serena Favorini, Anna Dal Col (Azienda Ospedaliera Università San Martino, Genova, Medicina III); Salvatore Minisola, Luciano Colangelo (Policlinico Umberto I, Roma, Medicina Interna F e Malattie Metaboliche dell’osso); Antonella Afeltra, Pamela Alemanno, Benedetta Marigliano (Policlinico Campus Biomedico Roma, Roma, Medicina Clinica); Pietro Castellino, Julien Blanco, Luca Zanoli (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico Vittorio Emanuele Ferrarotto, Santa Marta, S. Bambino, Catania, Dipartimento di Medicina); Marco Cattaneo, Paola Fracasso, Maria Valentina Amoruso (Azienda Ospedaliera San Paolo, Milano, Medicina III); Valter Saracco, Marisa Fogliati, Carlo Bussolino (Ospedale Cardinal Massaia Asti, Medicina A); Vittorio Durante, Giovanna Eusebi, Daniela Tirotta (Ospedale di Cattolica, Rimini, Medicina Interna); Francesca Mete, Miriam Gino (Ospedale degli Infermi di Rivoli, Torino, Medicina Interna); Antonio Cittadini, Michele Arcopinto, Andrea Salzano, Emanuele Bobbio, Alberto Maria Marra, Domenico Sirico (Azienda Policlinico Universitario Federico II di Napoli, Napoli, Medicina Interna e Riabilitazione Cardiologica); Guido Moreo, Francesco Scopelliti, Francesca Gasparini, Melissa Cocca (Clinica San Carlo Casa di Cura Polispecialistica, Paderno Dugnano, Milano, Unità Operativa di Medicina Interna).

Spanish Hospitals Ramirez Duque Nieves (Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocio, Sevilla); Muela Molinero Alberto (Hospital de Leon); Abad Requejo Pedro, Lopez Pelaez Vanessa, Tamargo Lara (Hospital del Oriente de Asturias, Arriondas); Corbella Viros Xavier, Formiga Francesc (Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge); Diez Manglano Jesus, Bejarano Tello Esperanza, Del Corral Behamonte Esther, Sevil Puras Maria (Hospital Royo Villanova, Zaragoza); Manuel Romero (Hospital Infanta Elena Huelva); Pinilla Llorente Blanca, Lopez Gonzalez-Cobos Cristina, Villalba Garcia M. Victoria (Hospital Gregorio Marañon Madrid); Lopez Saez, Juan Bosco (Hospital Universitario de Puerto Real, Cadiz); Sanz Baena Susana, Arroyo Gallego Marta (Hospital Del Henares De Coslada, Madrid); Gonzalez Becerra Concepcion, Fernandez Moyano Antonio, Mercedes Gomez Hernandez, Manuel Poyato Borrego (Hospital San Juan De Dios Del Aljarafe, Sevilla); Pacheco Cuadros Raquel, Perez Rojas Florencia, Garcia Olid Beatriz, Carrascosa Garcia Sara (Hospital Virgen De La Torre De Madrid); Gonzalez-Cruz Cervellera Alfonso, Peinado Martinez Marta (Hospital General Universitario De Valencia); Ruiz Cantero Alberto, Albarracín Arraigosa Antonio, Godoy Guerrero Montserrat, Barón Ramos Miguel Ángel (Hospital De La Serrania De Ronda); Machin Jose Manuel (Hospital Universitario De Guadalajara); Novo Veleiro Ignacio, Alvela Suarez Lucía (Hospital Universitario De Santiago De Compostela); Lopez Alfonso, Rubal Bran David, Iñiguez Vazquez Iria (Hospital Lucus Augusti De Lugo); Rios Prego Monica (Hospital Universitario De Pontevedra).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

GYHL: Steering committees for various Phase II and III studies, Health Economics and Outcomes Research. Investigator in various clinical trials in cardiovascular disease, including those on antithrombotic therapies in atrial fibrillation, acute coronary syndrome, lipids. Consultant for Bayer/Janssen, Astellas, Merck, Sanofi, BMS/Pfizer, Biotronik, Medtronic, Portola, Boehringer Ingelheim, Microlife and Daiichi-Sankyo. Speaker for Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Medtronic, Boehringer Ingelheim, Microlife, Roche and Daiichi-Sankyo. All the other authors have no interest to disclose.

Additional information

Members of REPOSI investigators are listed in acknowledgment.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Proietti, M., Nobili, A., Raparelli, V. et al. Adherence to antithrombotic therapy guidelines improves mortality among elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from the REPOSI study. Clin Res Cardiol 105, 912–920 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-016-0999-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-016-0999-4