Abstract

Purpose

The anti-anginal efficacy of the selective If inhibitor ivabradine has been demonstrated in controlled clinical trials. However, there is limited information about the safety and efficacy of a combined treatment of ivabradine with beta-blockers, particularly outside of clinical trials in every day practice. This analysis from the REDUCTION study evaluated the safety and efficacy of a combined therapy of beta-blockers and ivabradine in every day practice.

Methods

In this multi-center study 4,954 patients with stable angina pectoris were treated with ivabradine in every day routine practice and underwent a clinical follow-up for 4 months. 344 of these patients received a co-medication with beta-blockers. Heart rate (HR), angina pectoris episodes, nitrate consumption, overall efficacy and tolerance were analyzed.

Results

After 4 months of treatment with ivabradine HR was reduced by 12.4 ± 11.6 bpm from 84.3 ± 14.6 to 72.0 ± 9.9 bpm, p < 0.0001. Angina pectoris episodes were reduced from 2.8 ± 3.3 to 0.5 ± 1.3 per week, p < 0.0001. Consumption of short-acting nitrates was reduced from 3.7 ± 5.6 to 0.7 ± 1.7 units per week, p < 0.0001. Five patients (1.5%) reported adverse drug reactions (ADR). The most common ADR were nausea and dizziness (<0.6% each). There was no clinically relevant bradycardia. Efficacy and tolerance were graded as ‘very good/good’ for 96 and 99% of the patients treated.

Conclusion

Ivabradine effectively reduces heart rate and angina pectoris in combination with beta-blockers and is well tolerated by patients in every day practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A high heart rate can induce myocardial ischemia and angina pectoris symptoms in patients with coronary artery disease [1–3]. Therefore, recent guidelines for the treatment of stable angina pectoris recommend to reduce heart rate to 55–60 bpm [4–6]. Various studies in different populations have shown that a low heart rate at rest is associated with low total and cardiovascular mortality [7–9]. Recently, the BEAUTIFUL study demonstrated the importance of resting heart rate on cardiovascular events in a prospective manner in patients with coronary artery disease [10, 11].

Ivabradine reduces heart rate by its specific action on the sinus node [12]. It inhibits the If current of pacemaker cells with subsequent exclusive heart rate reduction [13]. Beta-blockers, in contrast, act via beta-receptors in various organs. Therefore, they exhibit various effects beside heart rate reduction. Since beta-blockers and ivabradine act via different pathways on the sinus node, they act in complementary and at least by partially additive mechanisms.

There are several clinical scenarios which raise the desire to use beta-blockers and ivabradine simultaneously. These are, for instance, the patients that are still symptomatic or have an insufficient heart rate reduction after high dose of beta-blocker therapy or the patients who tolerate only small doses of beta-blocker and gets side effects with higher doses. Subpopulations from two recently published trials indicated that beta-blocker therapy and ivabradine can be combined [10, 14]. However, the data were evaluated under clinical trial conditions and a variety of patients with co-morbidities, such as advanced renal insufficiency or a low heart rate were excluded. On the other hand, also patients with normal findings, such as a normal left-ventricular function were excluded in the BEAUTIFUL trial [10, 11].

Patients in controlled clinical trials do not represent every day populations because they are subject to a substantial selection and are more thoroughly followed-up [15]. In most cases, the patients, who consent to participate in a controlled clinical study have a better compliance than the common patient treated in every day routine practice. Multi-morbid patients and patients with polytherapy are often excluded from controlled clinical trials [16, 17]. Therefore, there is the need for evaluating whether favorable results from clinical studies measure up in every day practice. The open-label REDUCTION study demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the treatment of patients with chronic stable angina pectoris with ivabradine in a large patient population of 4,954 patients under every day practice conditions [18].

In this subgroup analysis from the REDUCTION study, we evaluated whether a combined therapy of ivabradine and beta-blockers is safe and efficient in every day routine practice.

Methods

Design

The study was conducted as a multi-center, prospective, open-label, non-interventional study. 4,954 patients who were treated with ivabradine were included and were prospectively followed by 1,503 general practitioners, internal medicine physicians, and cardiologists in private practice in Germany. All investigating physicians filled out a standardized questionnaire during the treatment of the patient.

The study is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was conducted in agreement with the ethical guidelines of the European Independent Ethics Committee.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were included if they were in sinus rhythm and if there was a need for symptomatic treatment of chronic stable angina pectoris.

The patients had the following differential indications for treatment with ivabradine:

-

initial medical therapy for chronic stable angina pectoris;

-

change in the patient’s medical treatment during therapy for chronic stable angina pectoris because of drug intolerance/side effects, insufficient efficacy or contraindication;

-

supplementation of the ongoing medical regimen for stable angina pectoris with or without concomitant disease.

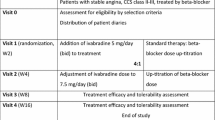

Treatment was initiated with ivabradine 5 mg twice daily. Increase in dose was possible after 2–4 weeks up to a target dose of 7.5 mg twice daily.

A lower dose of 2.5 mg of ivabradine twice daily was suggested in patients with the following features: Age ≥75 years, renal insufficiency with a creatinine clearance <15 ml/min, heart rate continuously <50 bpm during treatment, or symptomatic bradycardia.

Clinical examinations

Three clinical visits were performed: one at baseline and one after approximately 1 and 4 months of ivabradine treatment. At the first visit, the general and the cardiac history were documented. Cardiac risk factors, concomitant disease and other therapies were recorded. Heart rate and blood pressure were measured. The number of angina pectoris attacks within the week prior to the visit and the use of short-acting nitrates (nitrate capsules and hubs) were registered. The participating cardiologists optionally performed an electrocardiogram (ECG) at each visit.

The first follow-up examination was done after 2–4 weeks. At this time, blood pressure, heart rate, number of angina pectoris episodes within the last week and the consumption of short-acting nitrates were recorded. The dose of ivabradine was changed when necessary, and suspected adverse drug reactions (ADRs) were evaluated. The second control visit followed after approximately 4 months. At this time, the same clinical controls as after 4 weeks were performed. In addition, the change in concomitant therapy was recorded and a final grading of the efficacy and tolerance of ivabradine therapy was compiled according to the physician’s assessment using a scale including ‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘moderate’ or ‘poor’.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive statistical analysis was performed, assisted by SAS® software, version 9.1. Patients were considered if they had valid data from all visits. The changes in blood pressure and heart rate were calculated using the one sample t test. Differences in the numbers of angina pectoris episodes and in the necessity to use anti-anginal drugs were evaluated by the Wilcoxon’s signed rank test. Values are expressed as mean ± SD. A p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Study population

Of the 4,954 patients 344 were treated with ivabradine and beta-blockers. The following data refer to this group with beta-blockers. 59% of the patients were male, 41% female. The mean age was 66 ± 11 years. 285 patients (83%) had arterial hypertension and 279 (81%) hypercholesterolemia, 169 (49%) suffered from overweight, 121 (35%) had diabetes mellitus and 73 (21%) were smokers or ex-smokers.

The mean duration of coronary artery disease in the group was 6.3 ± 6.2 years. The mean duration of the history of angina pectoris was 4.2 ± 4.6 years. The CCS classification of angina pectoris of the patients is given in Table 1 [19].

Concomitant diseases, medication and procedures

In general, patients were pretreated with a beta-blocker and ivabradine was given on top. A previous percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) had been performed in 194 (59%) of the patients. 71 patients (22%) had already been treated with coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG). A PCI or CABG surgery or both had been performed in 223 (66%) of the patients. 149 patients (45%) had a previous myocardial infarction.

Concomitant diseases were present in 215 patients (63%). They are specified in Table 2.

The most frequently used beta-blockers were metoprolol (41%), bisoprolol (27%), carvedilol (9%) and nebivolol (9%). The average daily doses of these were metoprolol 99.0 mg, bisoprolol 5.7 mg, carvedilol 22.5 mg, nebivolol 5.1 mg. During the observation period, the beta-blockers were stopped in 30 patients and reduced in dose in 15 patients. The main reasons for stop or reduction in beta-blockers included fatigue, depression and respiratory symptoms. In two patients, dose was increased and 28 patients received de novo beta-blockers.

The dose of ivabradine during follow-up is given in Table 3.

Therapy with ivabradine beside the beta-blocker was discontinued in 18 of 344 patients (5.4%). In five patients, intolerance was reported. In one patient, there was a sinus bradycardia with a heart rate around 40 bpm. After discontinuation of the drug, all side effects were reversible without any clinical sequelae. Three patients discontinued for insufficient effect, two patients for insufficient compliance, and eight patients discontinued independently on their own intention without reported reason or other reasons such as being symptom free.

Co-medication beside the beta-blocker and ivabradine treatment during the observation period was given in 330 patients (96%). This is shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Heart rate and ECG parameters

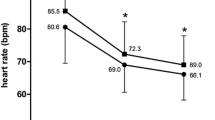

The heart rate was reduced by 12.4 ± 11.6 bpm from 84.3 ± 14.6 to 72.0 ± 9.9 bpm between baseline evaluation and the second follow-up visit after 4 months (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1).

Heart rate reduction under the combined treatment with ivabradine and beta-blocker in an observation period of 4 months. Average starting dosage was 8.7 mg at baseline, 10.2 mg at first month and 10.5 mg after 4 months. The given baseline value represents the heart rate under the therapy with beta-blockers before the start of therapy with ivabradine

No marked changes were seen in the ECG parameters, e.g. PQ-, QRS- and QTc periods as far as available. Relevant, but physiological changes were only observed in RR interval and in the uncorrected QT according to the reduction of heart rate.

Angina pectoris and nitrate consumption

77% of the patients had one or more angina pectoris episodes per week prior to the initiation of therapy with ivabradine. At the time of follow-up visit 4 months later, the frequency of angina pectoris episodes had been significantly reduced under ivabradine therapy (from 2.8 ± 3.3 to 0.5 ± 1.3 attacks per week, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2).

The consumption of nitrates (hubs and capsules) in the time between baseline and the follow-up visit after 4 months was significantly reduced in association with the treatment with ivabradine (3.7 ± 5.6 to 0.7 ± 1.7, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3).

The systolic mean blood pressure was reduced from 139.8 ± 18.0 to 130.2 ± 12.6 mmHg between baseline and the fourth month of treatment including ivabradine, beta-blockers and anti-hypertensive co-medication (−9.7 ± 14.9 mmHg). Diastolic mean blood pressure was reduced from 82.9 ± 10.7 to 77.5 ± 7.3 mmHg between the baseline visit and the follow-up after 4 months of treatment (−5.4 ± 9.8 mmHg).

The treating physicians regarded the efficacy of ivabradine as very good in 51.5% of the patients, as good in 44.6%, as moderate in 3.3% and as poor in 0.6% of the patients.

Adverse events/ADR

Eight suspected ADR were reported in five patients (1.5% of 344 patients, none of these were classified as severe). Most commonly were nausea (5 episodes in 2 patients) and dizziness (3 episodes in 2 patients). None of the patients complained about luminous phenomena (phosphenes). One patient developed headache. Cardiac ADR was reported in one patient with sinus bradycardia. This resolved without any sequel after discontinuation of ivabradine. There were no other cardiac side effects. There were no serious adverse events and no death.

Seven ADR were related to ivabradine in four patients (mainly gastrointestinal symptoms), one event was regarded to be definitively related (bradycardia), three probably related to ivabradine, three possibly related, and one was not evaluable.

The patient’s tolerance of ivabradine was graded as very good in 63.2% of the patients, as good in 36.2%, as moderate in 0.6% and as poor in 0.0% of the patients.

Discussion

Frequently, there is a discrepancy between the results of controlled clinical trials and the experience made in every day clinical practice [16]. This is partially due to specific patient selection in randomized clinical trials. Thus, observational data bases can give valuable additional information for the clinical use of a ‘new drug’. Therefore, this study evaluated the efficacy, safety and tolerance of ivabradine in combination with beta-blocker therapy deliberately under every day routine conditions.

The main finding from this study is that treatment with ivabradine in combination with beta-blockers is efficient and safe in the broad spectrum of patients in every day practice. On top of beta-blocker therapy, ivabradine achieved an additional heart rate reduction without induction of any critical bradycardia. Angina pectoris and nitrate consumption were further markedly reduced, whereas adverse effects, such as phosphens, occurred less frequent than expected from randomized and non-randomized trials [11, 14, 20].

This is the first study which covers the entire spectrum of patients seen in every day practice. The two other published trials, BEAUTIFUL and ASSOCIATE, which included patients with ivabradine and beta-blockers in selected groups of patients, suggested, that beta-blockers and ivabradine can be combined [11, 14]. However, both studies excluded a variety of patients. The BEAUTIFUL trial excluded all patients with an EF above 40% and included also patients without angina symptoms [11]. The ASSOCIATE trial included 30% of patients who had no angina pectoris in the run-in period, excluded patients with left bundle branch block, high grade renal insufficiency and disability to exercise [14]. In contrast to our study, the mean heart rate of the ASSOCIATE population was lower with 67 bpm at baseline [14]. These inclusion and exclusion criteria led to the evaluation of a population, which does not include all patient groups seen in daily practice. Insofar, our study extends the evaluation of ivabradine in combination with beta-blockers to new patient groups and provides information about patients not evaluated and described previously in the literature.

In our patient population, the heart rate reduction of 12 bpm under ivabradine was significant and occurred mainly at the first 4 weeks of treatment. The finding of further heart rate reduction by ivabradine, despite a pre-existing and ongoing beta-blocker therapy was consistent with that from the BEAUTIFUL trial, in which heart rate was reduced by 8 bpm [11]. One reason for the more pronounced heart rate reduction in the present trial can be a higher baseline heart rate in this study compared to that in the BEAUTIFUL trial.

However, the average heart rate of 72 bpm reached in our study was still relatively high for a population with chronic angina pectoris. One explanation for this effect may be underdosing of ivabradine. The average dose after 4 months was only 10.5 mg, whereas 15 mg would have been the maximum approved dose. This underdosage phenomenon has also been seen in other trials, such as the BEAUTIFUL trial, and may be related to a general and natural reservation of doctors to up-titrate novel drugs maximally. Because ivabradine was not maximally up-titrated, its effect on angina relief might have been underestimated in this trial and there may be more therapeutic potential than demonstrated yet.

Beta-blockers were not maximally dosed in this trial either, i.e. the mean dose of metoprolol was only 99 mg/day. This phenomenon is also well known from other trials, from common clinical practice, and from various surveys in patients with stable angina pectoris, heart failure and status post-myocardial infarction [21–23].

Despite the recommendation to up-titrate beta-blockers to full dosages, data in clinical practice usually show substantial underdosing of beta-blockers, with dosages ≤50% than the dosages that randomized trials have proved to be effective [21].

In the BEAUTIFUL trial, for instance, approximately half of the patients did not reach the target dose of the beta-blocker, for reasons, such as fatigue, dizziness, bradycardia, hypotension, and sexual dysfunction [24].

In the present study, this effect could partially be explained by reduced tolerability of higher doses of beta-blockers. Therefore, in patients who do not tolerate higher doses of beta-blockers or in whom sufficient symptom relief and heart rate reduction with beta-blockers cannot be achieved, the combination with ivabradine appears to be an appropriate therapeutic option. In clinical practice, the patient group, which raises physicians’ reservations against high-dose beta-blockers, include a wide variety of individuals with comorbidities [25, 26]. Apart from that there are patients that still have symptoms despite an optimal dose of beta-blockers. Regarding the large number of patients, in which the treating physician rather aims to a medium beta-blocker dose than to a high dose, or observes an insufficient anti-anginal effect with high doses, there appears to be a large therapeutic potential for the combination therapy with ivabradine to improve symptoms and to reach the recommended heart rate of 55–60 per min as a goal for the treatment of angina pectoris [4–6].

The blood pressure in our study was slightly reduced between baseline and the two follow-up visits. This cannot be explained by an ivabradine effect because ivabradine has been shown in multiple trials to have virtually no effect on blood pressure [27, 28].

In fact, the decrease in blood pressure can most likely be explained by the use of additional co-medication, such as calcium channel blockers or ACE inhibitors. The reduction in the blood pressure can also contribute to the relief of angina pectoris, so that the ivabradine effect may be overestimated [29]. However, the reduction in blood pressure was moderate and the whole reduction was completely within the normal blood pressure range, and, therefore, most likely irrelevant for the reduction in the angina attacks. Thus, after having taken this effect into account, exclusive heart rate reduction by ivabradine still appears to be the major factor for relief of symptoms.

Suspected ADR in this group were present in five patients (1.5%). These were mostly related to gastrointestinal discomfort or dizziness. There was one cardiac adverse reaction (0.3%), which consisted of a sinus bradycardia that disappeared after discontinuation of the ivabradine medication. The low rate of adverse events is in agreement with the results from other studies, such as the BEAUTIFUL trial [11, 27, 30]. This result suggests a high tolerance of ivabradine in combination with beta-blockers and also with various co-medications under every day conditions.

Visual adverse reactions, such as phosphens were not reported in this study. This is lower than expected from other trials, which reported 0.5–2% of phosphens [11, 14]. The lower rate of phosphens reported in this trial may be explained by the fact that the patients were interviewed in an open mode for side effects, and were not specifically asked for visual effects in the sense of phosphens. Previous studies showed that the rate of phosphens reported by specifically informed individuals has been four times higher compared with that reported by subjects who were unaware of it [31]. It is suggestive, that patients in clinical studies are more informed, and therefore aware of phosphens than those in every day practice. Hence, it can be assumed that they report it more frequently than patients do on their own intention in every day practice.

When considering the overall low rate of ADR in the study group with beta-blockers and ivabradine, it is comprehensible that the vast majority of the treating physicians considered the tolerance of ivabradine as excellent or very good.

Study limitations

A major limitation of this study is the open-label, observational non-interventional design. This can generate a bias to overestimate the clinical benefits of ivabradine; however, it closely represents every day practice reality. A further limitation is the short follow-up period of only 4 months.

When considering that the mean heart rate achieved in this study after 4 months was still rather high with 72 bpm, and that only 20% of the patients received the maximum dose of ivabradine of 7.5 mg twice daily, there was potential to increase the ivabradine dose, and potentially its beneficial effect, too. Thus, the therapeutic potential of ivabradine in this group appears not completely utilized and the clinical benefits may still remain underestimated. On the other hand, the relatively low dose may cause an underestimation of the adverse effects, which typically occur more often at higher doses.

The reduction in blood pressure as a probable result of the change of co-medication may also have reduced angina pectoris and may lead to overestimation of the ivabradine effect.

Conclusions

Ivabradine effectively reduces heart rate in combination with beta-blockers. This is associated with a marked reduction in angina pectoris attacks and nitrate consumption in every day practice.

Ivabradine in combination with beta-blockers was safe and well tolerated by the majority of patients without any relevant bradycardia. A combination of ivabradine with beta-blockers appears to be a reasonable treatment option for patients with chronic stable angina pectoris.

References

McLenachan JM, Weidinger FF, Barry J, Yeung A, Nabel EG, Rocco MB, Selwyn AP (1991) Relations between heart rate, ischemia, and drug therapy during daily life in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 83:1263–1270

Heusch G, Schulz R (2007) The role of heart rate and the benefits of heart rate reduction in acute myocardial ischemia. Eur Heart J 9(Suppl F):F8–F14

Möhlenkamp S, Lehmann N, Schmermund A, Roggenbuck U, Moebus S, Dragano N, Bauer M, Kälsch H, Hoffmann B, Stang A, Bröcker-Preuss M, Böhm M, Mann K, Jöckel KH, Erbel R, Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study Investigators (2009) Association of exercise capacity and the heart rate profile during exercise stress testing with subclinical coronary atherosclerosis: data from the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. Clin Res Cardiol 98(10):665–676

Fox K, Garcia MA, Ardissino D, Buszman P, Camici PG, Crea F, Daly C, De Backer G, Hjemdahl P, Lopez-Sendon J, Marco J, Morais J, Pepper J, Sechtem U, Simoons M, Thygesen K, Priori SG, Blanc JJ, Budaj A, Camm J, Dean V, Deckers J et al (2006) Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris. Eur Heart J 27:1341–1381

Fraker TD, Fihn SD (2007) Chronic Angina Focused Update of the ACC/AHA 2002 guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina. Circulation 116:2762–2772

Donner-Banzhoff N, Held K, Laufs U, Trappe HJ, Werdan K, Zerkowski HR. Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie Chronische KHK. Version 2008. http://www.versorgungsleitlinien.de/themen/khk/pdf/nvl_khk_lang.pdf. Accessed 22 January 2009

Kannel WB, Kannel C, Paffenbarger RS Jr, Cupples LA (1987) Heart rate and cardiovascular mortality: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J 113:1489–1494

Palatini P (2007) Heart rate as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Current evidence and basic mechanisms. Drugs 67(Suppl 2):3–13

Fox K, Borer J, Camm AJ, Danchin N, Ferrari R, Lopez Sendon JL, Steg PG, Tardiff JC, Tavazzi L, Tendera M (2007) Resting heart rate in cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 50:823–830

Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG, Tendera M, Robertson M, Ferrari R (2008) Heart rate as a prognostic risk factor in patients with coronary artery disease and left-ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 372(9641):817–821

Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG, Tendera M, Ferrari R, on behalf of the BEAUTIFUL investigators (2008) Ivabradine for patients with stable coronary artery disease and left-ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 372(9641):807–816

DiFrancesco D (2006) Funny channels in the control of cardiac rhythm and mode of action of selective blockers. Pharmacol Res 53:399–406

DiFrancesco D, Camm JA (2004) Heart rate lowering by specific and selective If current inhibition with Ivabradine. Drugs 64:1757–1765

Tardiff JC, Ponikowski P, Kahan T, for the ASSOCIATE study investigators (2009) Efficacy of the If current inhibitor ivabradine in patients with chronic stable angina receiving beta-blocker therapy: a 4 month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Heart J 30(5):540–548

Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI (2000) Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med 342:1887–1892

Pocock SJ, Elbourne DR (2000) Randomized trials or observational tribulations? N Engl J Med 342:1907–1909

Bonzel T, Erbel R, Hamm CW, Levenson B, Neumann FJ, Rupprecht HJ, Zahn R (2008) Percutaneous coronary interventions. Clin Res Cardiol 97(8):513–547

Köster R, Kaehler J, Meinertz T (2009) Treatment of stable angina pectoris by ivabradine in every day practice: the REDUCTION study. Am Heart J 158(4):e51–e57

Campeau L (1976) Grading of angina pectoris. Circulation 54:522–523

Zhang R, Haverich A, Strüber M, Simon A, Pichlmaier M, Bara C (2008) Effects of ivabradine on allograft function and exercise performance in heart transplant recipients with permanent sinus tachycardia. Clin Res Cardiol 97(11):811–819

Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstom SZ, Gadsboll N, Buch P, Friberg J, Rasmussen S, Kober L, Stender S, Madsen M, Torp-Pedersen C (2006) Long-term compliance with beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and statins after acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 27:1153–1158

Wiest FC, Bryson CL, Burmann M, McDonell MB, Henikoff JG, Fihn SD (2004) Suboptimal pharmacotherapeutic management of chronic stable angina in the primary care setting. Am J Med 117:234–241

Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Alberrt NM, Stough WG, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, O’Connor CM, Sun JL, Yancy CW, Young JB (2008) Dosing of beta-blocker therapy before, during, and after hospitalization for heart failure (from organized program to initiate lifesaving treatment in hospitalized patients with heart failure) 102:1524–1529

Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG, Tendera M, Robertson M, Ferrari R, on behalf of the BEAUTIFUL investigators (2009) Relationship between ivabradine treatment and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with stable coronary artery disease and left ventricular systolic dysfunction with limiting angina: a subgroup analysis of the randomized, controlled BEAUTIFUL trial. Eur Heart J 30(19):2337–2345

Wenzel P, Abegunewardene N, Münzel T (2009) Effects of selective I f -channel inhibition with ivabradine on hemodynamics in a patient with restrictive cardiomyopathy. Clin Res Cardiol 98(10):681–684

Link A, Reil JC, Selejan S, Böhm M (2009) Effect of ivabradine in dobutamine induced sinus tachycardia in a case of acute heart failure. Clin Res Cardiol 98(8):513–515

Tardiff JC, Ford I, Tendera M, Bourassa MG, Fox K (2005) Efficacy of ivabradine, a new selective If inhibitor, compared with atenolol in patients with chronic stable angina. Eur Heart J 26:2529–2536

Tardiff JC (2007) Clinical results of If current inhibition by ivabradine. Drugs 67(Suppl 2):35–41

Robinson BF (1967) Relation of heart rate and systolic blood pressure to the onset of pain in angina pectoris. Circulation 35:1073–1083

Borer JS, Fox K, Jaillon P, Lerebours G (2003) Antianginal and antiischemic effects of ivabradine, an If inhibitor, in stable angina. A randomized, double-blind, multicentered, placebo-controlled trial. Circulation 107:817–823

Siegel RK (1977) Hallucinations. Sci Am 237:132–140

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dieter Schremmer from the ‘Gesellschaft für Therapieforschung’ in Munich, Germany, for his substantive support of the statistical analysis, and all investigators for their contributions to the study. The investigators participated were J. Taggeselle, L. Feß, R. Aubele, N. Hassler, K. Hofmann, V. Adelberger, T. Arnold, B. Holz, M. Hwaidi, H.-D. Kombächer, R. Meysing, S. Appel, J. Bazowski, R. Bernauer, H. Böneke, M. Braun, E. Daelmann, M. Deißner, S. Duddy, M.-A. Eisenbarth, H. Fissan, C. Freese, G. Gölz, M. Gutting, K. Hallbaum, M. Hilgedieck, J.-A. Hintze, H. Hohensee, T. Hohenstatt, O. Khan, H.-H. Knäbchen, A. Krämer, K. Krämer, R. Lange, A. Levertov, H. Littwitz, U. Meyer, K. Müller, L. Rokitzki, C. Ruhnau, K. Rybak, R. Schmitt, A. Spingler, H. Stellmach, R. Tietze, W. Türk, R. Vormann, T.-A. Wiegmann, G. Will, E. Wüstenberg, J. Zivojinovic. The list of the further investigators is available from the corresponding author. TM’s, KW’s, HE’s, GS’s and RK’s participation at scientific congresses has been supported by Servier Deutschland. The study was supported by funding from Servier, Germany.

Conflict of interest statement

TM is member of the advisory board. JK has no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

On behalf of the Reduction Study Investigators

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Koester, R., Kaehler, J., Ebelt, H. et al. Ivabradine in combination with beta-blocker therapy for the treatment of stable angina pectoris in every day clinical practice. Clin Res Cardiol 99, 665–672 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-010-0172-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-010-0172-4