Abstract

Background

Little is known to what extent general practitioners (GP) change hospital discharge medications in older patients.

Objective

This prospective cohort study aimed to analyze medication changes at the interface between hospital and community in terms of quality, quantity and type of drugs.

Methods

A total of 121 out of 248 consecutively enrolled patients admitted to an acute geriatric hospital unit participated in the study. Medication regimens were recorded at admission and discharge and 4 weeks after hospital discharge the general practitioners in charge were contacted to provide the current medication charts. Changes in the extent of polypharmacy, in the type of drugs using anatomical therapeutic chemical classification (ATC) codes and potentially inappropriate medications (PIM) were analyzed.

Results

Medication charts could be obtained for 98 participants in primary care. Only 21% of these patients remained on the original discharge medication. Overall, the average number of medications rose from hospital admission (6.58 SD ± 3.45) to discharge (6.96 SD ± 3.49) and again post-discharge in general practice (7.22 SD ± 3.68). The rates of patients on excessive polypharmacy (≥10 drugs) and on PIM were only temporarily reduced during hospital stay. The GPs stopped anti-infective drugs (ATC-J) and prescribed more antirheumatic drugs (ATC-M). Although no significant net changes occurred in other ATC groups, a substantial number of drugs were interchanged regarding the subgroups.

Conclusion

The study found that GPs extensively adjusted geriatric discharge medications. Whereas some changes may be necessary due to alterations in patients’ state of health, a thorough communication between hospital doctors and GPs may level off different prescribing cultures and contribute to consistency in medication across sectors.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Es ist nur wenig über Art und Umfang von Medikationsänderungen bei geriatrischen Patienten an der Schnittstelle von Krankenhausentlassung und hausärztlicher Versorgung bekannt.

Ziel

Ziel dieser prospektiven Studie ist es, die Änderungen der Medikation in Hinblick auf die Qualität und Quantität genauer zu analysieren.

Methoden

Von 248 Patienten, welche in eine geriatrische Klinik eingewiesen wurden, nahmen 121 Patienten teil. Die Medikationspläne wurden bei Aufnahme, bei Entlassung und 4 Wochen nach der Entlassung (über Kontakt zum jeweiligen Hausarzt) erfasst und auf den Anteil an Polypharmazie, potenziell inadäquater Medikation (PIM) sowie Art der Medikation (ATC-Code) hin analysiert.

Ergebnisse

Für 98 Patienten lagen die Medikationspläne vollständig vor. Nur bei 21 % der Patienten führten die Hausärzte die Medikation unverändert fort. Insgesamt zeigte sich eine Zunahme der Medikamentenanzahl zwischen Aufnahme (6,58 Standardabweichung [SD] ± 3,45), Entlassung (6,96 SD ± 3,49) und 4 Wochen nach der Entlassung (7,22 SD ± 3,68). Der Anteil an Patienten mit schwerer Polypharmazie (≥10 Medikamente) und PIM konnte durch den Krankenhausaufenthalt nur temporär reduziert werden. Die Hausärzte beendeten Antiinfektiva (ATC-J) und setzten signifikant mehr Antirheumatika (ATC-M) an. In den weiteren Subgruppen kam es zu wesentlichen, aber nicht signifikanten Änderungen.

Schlussfolgerung

Hausärzte ändern die Entlassungsmedikation geriatrischer Patienten in großem Umfang. Auch wenn manche Änderungen möglicherweise einem veränderten Gesundheitszustand der Patienten geschuldet sind, könnte dennoch eine bessere Kommunikation an der Schnittstelle dazu beitragen, das jeweilige Verschreibungsverhalten abzugleichen und eine Kontinuität der Medikation zu gewährleisten.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hospital discharge is a critical phase in patient care due to the transition from one healthcare setting to another. This is especially true for the therapeutic interventions in older patients suffering from multimorbidity. They often present with a high prevalence of polypharmacy (PP) and potentially inappropriate medications (PIM). Geriatric units in hospitals are aware of these medication-related risks and use decision support tools to assist in safe prescription, e.g. START criteria [20] or the FORTA list [16]; however, studies have shown that medication issues particularly arise in the discharge phase. A variety of factors have been made responsible, such as reconciliation errors, mismatch of dosages, non-adherence and confusing substitutions [18, 25]. Moreover, patients are often not aware of medication changes, have little knowledge about the discharge medication [5] and are confronted with unfamiliar routines in handling new medications [7]. Delays in issuing discharge letters with the medication charts seem to contribute towards re-hospitalization [27]. Hence the medication transition phase after discharge seems to pose a significant risk for older patients, often contributing to deteriorating illnesses and impaired health outcomes [25].

Despite the observed issues in the medication management of older patients and the inherent risks of adverse drug events post-discharge [15], few studies have sought descriptive evidence on the medication changes that occur in this transitional phase. In a prospective study focusing on the post-discharge period, only 16% of the geriatric patients remained on the hospital prescriptions after 1 month. A third of all medications had been modified [18]. Likewise, a Danish study demonstrated that 64% of the drugs from a geriatric hospital were continued by primary care doctors. The acceptance rate was somewhat lower for the newly initiated medications during hospital stay [17]. In another study initiated on general medical wards, it was observed that the number of drugs increased during hospital stay from an average of 5.6 to 7.6 medications. General practitioners (GP) altered the discharge medication charts for 86% of patients in the 4–5 month follow-up period. Only every fourth discharge letter had arrived timely within 1 week [28].

With the complexity of medication management of older geriatric patients in mind, this study aims to:

-

examine to what amount discharge medication is maintained in primary care by the GPs,

-

compare the rate of patients on excessive polypharmacy in hospital vs. post-discharge in primary care,

-

analyze appropriate prescription of medication in this transition phase using PIM as an indicator,

-

identify medications using anatomical therapeutic chemical classification (ATC) codes which are more likely to be stopped or continued by GPs.

Methods

Study design

The prospective cohort study was set in the Center for Medicine of the Elderly (CME), one of Hannover’s three geriatric inpatient units. Approval was given by the ethics committee at the Hannover Medical School (Nr. 2350-2014). Data were collected at three points in time: at hospital admission (T0), discharge (T1) and 4–6 weeks after discharge into primary care (T2).

Setting and study participants

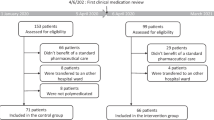

From 6 October to 1 December 2014 all patients admitted to the acute wards of CME were approached during an 8‑week period. Patients either directly came from the emergency unit or had been admitted from surrounding hospitals because of their geriatric conditions. Informed consent was sought during hospital stay and in many cases there was a need for additional consent by the next of kin or other caregivers. The inclusion criterion was admittance to acute geriatric care. Exclusion criteria were assignment to a geriatric rehabilitation ward or outpatient clinic, short stay patients from the memory clinic and no informed consent. Figure 1 shows the recruitment chart.

Study procedure, data collection and outcome

At admission, patient data were collected using the standard admission protocol, including age, gender, and medications from the current hospital medication charts. Over the counter (OTC) and complementary drugs were not taken into account. Information on glomerular filtration, mini mental status examination (MMSE) and the 15-item geriatric depression scale was acquired within the first 3 days. Functional abilities (Barthel index) and the timed up and go test were tested twice, at the beginning and end of hospitalization. Participating inpatients were treated with the established medical standards without involvement of a pharmacist. Patients’ medications were documented again at discharge using the discharge letter to the GP. The primary and secondary diagnoses were also taken from the discharge letter. These unsealed letters are routinely given to patients to pass on to their GPs. The respective GPs were contacted for the first time 4–6 weeks after discharge when they were informed about the study and asked to provide the current medication chart. The medication count, the ATC codes, polypharmacy measures and PIM were used as outcome indicators. To describe the type of drug, each medication received an ATC code using one level for the therapeutic main group [19]. Likewise, each medication was screened for potential inappropriateness. For this purpose the PRISCUS list [13] was consulted, which is the equivalent to the Beers list [1] in German-speaking countries. The PP was defined as regularly taking five or more medications and excessive PP as taking ≥10 drugs.

Statistical analysis

Patient medication lists were then matched at all three points in time (T0, T1, T2). Descriptive analyses and significance testing on changes were performed with SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to evaluate the difference between the. ATC groups.

Results

Participants

During the study period 248 patients were admitted to CME and 121 patients (66.9%) took part in the study (see recruitment flow chart, Fig. 1). Of the patients 56 came from the emergency department, 29 from other acute wards (internal medicine, surgery) within the hospital, 27 patients from surrounding hospitals and 9 patients with a referral directly from a GP. After discharge it was possible to follow up 98 (81%) patients because the GPs were able to send the current complete medication chart but 23 patients could not be followed up, e.g. they moved to a new care facility and changed the GP. These 98 patients were registered by 80 different GPs: 69 GPs had 1 patient, 7 GPs 2 patients, and 4 GPs had 3–5 study patients.

Patient characteristics and assessment results

A total of 86 (71.1%) female and 35 male patients took part with an average age of 83 years (range 63–96 years). They stayed on average 20 ± 12 days on the geriatric unit (range 2–56 days). The mean glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was 85.0 ml/min/kg2 (SD ± 39.0). Table 1 provides further patient characteristics and assessment results. All patients had one primary diagnosis, which is generated to receive reimbursement for the geriatric patient case and coded according to the German modification of ICD 10. The most frequent primary diagnoses were: immobility syndrome (ICD M62.3), frailty syndrome (ICD R54) followed by pneumonia (ICD J18), dehydration (ICD E86), congestive heart disease (ICD I50) and syncope (ICD R55). Additionally, a mean of 5.9 further secondary diagnoses were recorded due to German coding guidelines for inpatients. The commonest were hypertension (n = 93, 76.9%), anemia (n = 31, 25.6%), atrial fibrillation (n = 30, 24.8%), dementia (n = 29, 24.0%), type 2 diabetes mellitus and congestive heart disease (each n = 28, 23.1%).

Number of medications, PP and excessive PP, and PIM

Medications were surveyed at three points in time (Table 2). During hospital stay a non-significant rise in the number of medications occurred. Subsequently, in primary care after adjustments by GPs, patients were prescribed on average 7.2 different drugs, overall a significant increase (p = 0.015) compared to hospital admission and a non-significant increase (p = 0.131) compared to discharge.

Focusing on the post-discharge period, only 21 patients (21.4%) remained exactly on the hospital medication. Altogether, 36.7% of patients encountered no difference in the net number of drugs and 28.6% had a net decrease in drugs while 34.7% had a net increase. Figure 2 gives an overview over the net differences in drugs post-discharge: GPs discarded up to 8 drugs and newly prescribed up to 6 drugs per patient.

Polypharmacy was present in 72 (73.5%) patients at admission. The percentage of patients on polypharmacy tended to increase during hospital stay and again in the post-discharge phase; however, the number of patients on excessive PP declined during hospital (p = 0.999) stay but increased insignificantly post-discharge (p = 0.092) (Table 2). The rate of patients on PIM diminished during hospital stay from 21 patients (21.4%) with at least 1 PIM at admission to 17 patients (17.3%, p = 0.019) at discharge. Post-discharge in primary care, a significant rise could be observed (23.5%, p = 0.034). The most common PIMs at discharge were acetyldigoxin (n = 5) and zolpidem (n = 4), in primary care they were acetyldigoxin (n = 6) and dimenhydrinate (n = 4). Many changes occurred, however, acetyldigoxin and doxazosin were generally continued.

Post-discharge changes regarding ATC groups

Significant changes occurred for the ATC groups J (anti-infective agents) and M (musculoskeletal). Additionally, frequent switches without a significant shift in the net difference of drugs were observed. Of the patients receiving drugs within the ATC groups A, N and R more than 50% of patients experienced an exchange of drugs (Fig. 3).

Number of patients with net medication changes per ATC groups post-discharge. aATC group (1st level, anatomical main group): A alimentary tract and metabolism, B blood and blood forming organs, C cardiovascular system, G genitourinary system and sex hormones, H systemic hormonal preparations, excluding sex hormones and insulins, J anti-infective agents for systemic use, M musculoskeletal system, N nervous system, R respiratory system, S sensory organs. bNumber of patients with medications in the particular ATC group at discharge/post-discharge. cPercentage of patients with and without changes for this ATC group

ATC group J (anti-infective agents for systemic use)

GPs stopped all antibiotics (−6 drugs), which had been initiated in clinic for acute infections.

ATC group M (musculoskeletal system)

Out of 24 patients receiving group M drugs 14 had changes. Most of the changes consisted of the addition of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (ibuprofen and diclofenac, 9 out of 14 patients) after discharge to primary care.

ATC group A (alimentary tract and metabolism)

Of the patients 78 were prescribed class A drugs at hospital discharge and 60% of these patients experienced changes in their class A drugs post-discharge. They were either discontinued (for 27 drugs in 21 patients) or started (33 drugs in 26 patients). The majority of changes occurred for vitamin D and proton pump inhibitors, which GPs usually started. By contrast, they discontinued minerals (potassium, calcium, magnesium).

ATC group N (nervous system)

Of the patients on ATC‑N drugs 55% experienced alterations. The GPs discontinued benzodiazepines and Z‑drug use (omission in 7 of 10 patients). They started some patients on antidepressants (5 times) after discharge. Changes also occurred in the pain management: Oxycodone and paracetamol were predominately stopped (5 times each), whereas metamizole and tilidine/naloxone were started (10 and 5 times, respectively).

ATC group R (respiratory system)

Of the patients on ATC‑R drugs 68% had alterations. Anticholinergics (e.g. tiotropium bromide, 4 patients) and corticoids for inhalation (4 patients) were discontinued. At the same time GPs started other patients on anticholinergics (+4) and betamimetics (+7 times).

Drugs of the ATC groups B, G, H, and S were mostly left unchanged (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Changes in medications in hospital and after discharge

In this observational study of 98 patients admitted to and discharged from a geriatric clinic, the number of drugs increased during hospital stay and again post-discharge. This demonstrates the challenge of managing old and multimorbid patients with a considerable number of chronic and acute illnesses that repeatedly generate the need for multiple drugs. Thus, a hospital stay for older patients is a cause for changes and even an increase in the number of medications [14, 17]. This study focused on the stability of medication regimens for geriatric patients in the post-discharge period. Only 21% of the patients remained on the medication plan made at discharge. The GPs started more medications than they stopped, which led to the average rise in drugs of about 1 drug for every second patient. This also caused a rise of excessive PP. The GPs additionally prescribed more PIM than doctors on geriatric wards.

Changes in ATC codes after discharge

In this study, GPs stopped anti-infective drugs (ATC-J) post-discharge and prescribed significantly more non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID, ATC-M) on demand. In the 3 main ATC groups (C = cardiovascular system; N = nervous system; A = alimentary tract and metabolism) a wide range of adjustments took place, yet with no net significant change. Noticeably the opioid oxycodone was stopped and metamizole was added, probably replacing a “heavy” pain killer with a “lighter” one. Pantoprazole in ATC‑A also stood out as GPs either started or stopped this drug.

The detailed analysis of the types of drug changes showed that GPs avoided prescribing strong opioids (oxycodone) for pain management and used NSAID, metamizole and tilidine/naloxone as replacements. This might be due to side effects of opioids following hospital discharge [8] and the difficulties of long-term (strong) opioid prescription. The GPs also started some patients on antidepressants after discharge. A rise of depression after hospital discharge has been observed elsewhere [22]. In most patients taking benzodiazepines (and Z‑drugs) during the hospital stay, GPs discontinued these drugs. In contrast, a secondary data analysis from Canada showed that there is a risk of keeping older patients on temporarily prescribed benzodiazepines after discharge [24]. The GPs in the present study started patients on PPI after discharge. There are hints that prescription of PPI in primary care might be associated with age and gender of the prescribing doctors and e.g. the number of patients per GP [12]. The divergence in the prescription of vitamin D might be explained by uncertain long-term effects of vitamin D supplementation [3]. Remarkably, GPs alter the discharge medication very frequently, often adding medication and discontinuing medication simultaneously. This might indicate that GPs regularly practice reviewing patients’ medications using the longstanding knowledge about their patients’ medical history, preferences and appropriate or inappropriate medications [4]. Moreover, this might mirror the changed health status of the patient back in primary care, e.g. as patients return to their baseline mobility (resulting in more NSAIDs on demand).

Intersectional medication management: problems and solutions

Hospital discharge is a complex and a vulnerable situation for patients and professionals, where many things might cause confusion (communication failures, incorrect documentation etc.) [7]. This shows the need for intersectional communication with standard procedures in place that are beneficial concerning e.g. readmission to hospital [21]. Hence, the medication should be a major focus in the post-discharge period. A smaller retrospective study showed that discharge summaries are often incorrect and that most of the medication changes in hospital are not communicated thoroughly to the GPs [9]. A recent qualitative study focused on GPs’ experiences concerning the handover from hospital to primary care: miscommunication between geriatric hospital doctors and GPs, delayed discharge letters and missing structures for scheduled follow-up visits [26]; however, there could be ways of improving the cross-sectional medication management. In hospital, the geriatric patients’ medication should be revised using electronic devices [2, 6] and standardized blacklists and positive lists, such as the FORTA list on geriatric wards [29]. Additionally, information for patients and the next of kin before discharge with a special notice on changes of drugs was helpful [5]. The medication changes could reach the GPs in advance as was done in a recent German study with 200 enrolled patients in a teaching hospital [10]. This procedure reduced the rate of patients with potentially hazardous medication changes (e.g. discontinuation of an indicated drug) after discharge by 39% in the intervention group (p < 0.001) compared to the control group. Tools on how to improve intersectional medication procedures are being tested [23], e.g. using a standardized deprescribing and communication platform linking hospitals to the GPs [11]. The communication pathway should not be one-sided as GPs also need a chance to communicate the often long standing knowledge about the patients to the hospital doctors, e.g. in quality circles or web conferences.

Strengths and limitations

This study explored the issues of post-discharge medication changes more in detail. The great majority of geriatric patients could be followed up in primary care and the medication was analyzed in ATC codes, showing the high amount of alterations e.g. in pain medication (NSAID). The 98 study patients with complete medication charts had 80 different GPs, which reduces any potential cluster effect.

It was not possible to receive the GPs’ medication charts before admission. The medication chart on arrival at the geriatric ward usually came from the referring ward/hospital. Thus, the medication at admission is potentially modified and does not necessarily reflect the last medication schedules prior to hospitalization. Hospital standards on preferred drug regimens (e.g. replacement of furosemide with torasemide or vice versa) need to be considered as well. It is known that certain medication changes undertaken in geriatric units are also due to the patients’ initial poor health on admission in the first place. The patients were not asked about any OTC and complementary drugs, this might well have played a role in medication safety. Furthermore, the study did not assess changing of drug regimens in terms of short-term or long-term treatment or changes of dosage. Finally, GPs in primary care were not asked if they had received a complete discharge letter and for their reasons of adding or stopping medications.

Whether these medication changes observed during hospitalization and the transition phase back to primary care are adequate, could be another subject under scrutiny, yet little evidence has been generated so far. Future research is also required to evaluate the post-discharge medications changes in a larger sample and to study the effects of changes with longer follow-up. The GPs reasons of changing medications and conceptions/guidance on how medications in the post-discharge are optimally managed could also be an issue for further research.

Conclusion

Post-discharge, it was observed that GPs adjust the medications of geriatric patients up to a high amount. In this prospective study, this has led to small increases in polypharmacy, excessive polypharmacy and PIM. In the process of medication adjustments, GPs favored prescribing NSAID and antidepressants over opioids and stopped benzodiazepines and Z‑drugs. Further research is required to investigate pragmatic approaches on how to improve post-discharge prescription and deprescription patterns and communication between clinicians (e.g. geriatricians) and GPs.

References

American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel (2012) American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 60:616–631

Ammenwerth E, Schnell-Inderst P, Machan C et al (2008) The effect of electronic prescribing on medication errors and adverse drug events: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 15:585–600

Bolland MJ, Grey A, Avenell A (2018) Effects of vitamin D supplementation on musculoskeletal health: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 6:847–858

Clyne B, Cooper JA, Hughes CM et al (2016) ‘Potentially inappropriate or specifically appropriate?’ Qualitative evaluation of general practitioners views on prescribing, polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people. BMC Fam Pract 17:109

Freyer J, Greissing C, Buchal P et al (2016) Discharge medication—what do patients know about their medication on discharge? Dtsch Med Wochenschr 141:e150–e156

Frisse S, Röhrig G, Franklin J et al (2016) Prescription errors in geriatric patients can be avoided by means of a computerized physician order entry (CPOE). Z Gerontol Geriatr 49:227–231

Garcia-Caballos M, Ramos-Diaz F, Jimenez-Moleon JJ et al (2010) Drug-related problems in older people after hospital discharge and interventions to reduce them. Age Ageing 39:430–438

Goldsmith H, Curtis K, McCloughen A (2017) Effective pain management in recently discharged adult trauma patients: Identifying patient and system barriers, a prospective exploratory study. J Clin Nurs 26:4548–4557

Gracie R, Randall E, Alexander H (2014) A retrospective survey of elderly patients’ discharge summaries: are inpatient medication changes communicated to GPs? Age Ageing 43:ii2–ii3

Greissing C, Buchal P, Kabitz HJ et al (2016) Medication and treatment adherence following hospital discharge. Dtsch Arztebl Int 113:749–756

Grischott T, Zechmann S, Rachamin Y et al (2018) Improving inappropriate medication and information transfer at hospital discharge: study protocol for a cluster RCT. Implement Sci 13:155

Haastrup PF, Rasmussen S, Hansen JM et al (2016) General practice variation when initiating long-term prescribing of proton pump inhibitors: a nationwide cohort study. BMC Fam Pract 17:57

Holt S, Schmiedl S, Thürmann PA (2010) Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: the PRISCUS list. Dtsch Arztebl Int 107:543–551

Hopcroft P, Peel NM, Poudel A et al (2014) Prescribing for older people discharged from the acute sector to residential aged-care facilities. Intern Med J 44:1034–1037

Kanaan AO, Donovan JL, Duchin NP et al (2013) Adverse drug events after hospital discharge in older adults: types, severity, and involvement of Beers Criteria Medications. J Am Geriatr Soc 61:1894–1899

Kuhn-Thiel AM, Weiss C, Wehling M et al (2014) Consensus validation of the FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) List: a clinical tool for increasing the appropriateness of pharmacotherapy in the elderly. Drugs Aging 31:131–140

Larsen MD, Rosholm JU, Hallas J (2014) The influence of comprehensive geriatric assessment on drug therapy in elderly patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 70:233–239

Mansur N, Weiss A, Hoffman A et al (2008) Continuity and adherence to long-term drug treatment by geriatric patients after hospital discharge: a prospective cohort study. Drugs Aging 25:861–870

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology (2019) ATC/DDD Index. www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/. Accessed 21 May 2019

O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S et al (2015) STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing 44:213–218

Parsons M, Parsons J, Rouse P et al (2018) Supported discharge teams for older people in hospital acute care: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 47:288–294

Pederson JL, Majumdar SR, Forhan M et al (2016) Current depressive symptoms but not history of depression predict hospital readmission or death after discharge from medical wards: a multisite prospective cohort study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 39:80–85

Preyde M, Brassard K (2011) Evidence-based risk factors for adverse health outcomes in older patients after discharge home and assessment tools: a systematic review. J Evid Based Soc Work 8:445–468

Scales DC, Fischer HD, Li P et al (2016) Unintentional continuation of medications intended for acute illness after hospital discharge: A population-based cohort study. J Gen Intern Med 31:196–202

Sorensen L, Stokes JA, Purdie DM et al (2005) Medication management at home: medication-related risk factors associated with poor health outcomes. Age Ageing 34:626–632

Strehlau AG, Larsen MD, Sondergaard J et al (2018) General practitioners’ continuation and acceptance of medication changes at sectorial transitions of geriatric patients—a qualitative interview study. BMC Fam Pract 19:168

Van Walraven C, Seth R, Austin PC et al (2002) Effect of discharge summary availability during post-discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med 17:186–192

Viktil KK, Blix HS, Eek AK et al (2012) How are drug regimen changes during hospitalisation handled after discharge: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2:e1461

Wehling M, Burkhardt H, Kuhn-Thiel A et al (2016) VALFORTA: a randomised trial to validate the FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) classification. Age Ageing 45:262–267

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all participating geriatric patients (and their next of kin and legal representatives) and GPs.

Funding

This study was not supported by any kind of funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

O. Krause, S. Glaubitz, K. Hager, T. Schleef, B. Wiese and U. Junius-Walker declare that they have no competing interests.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was given by the ethics committees at the Hannover Medical School (Nr. 2350-2014).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krause, O., Glaubitz, S., Hager, K. et al. Post-discharge adjustment of medication in geriatric patients. Z Gerontol Geriat 53, 663–670 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-019-01601-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-019-01601-8