Abstract

Background

Suicide is a serious mental health problem in old age. Suicide ideation and life weariness are important psychopathological issues in geriatric medicine, although suicide ideation does not primarily depend on the severity of any physical disease. Despite these facts, insight into the internal psychological state of suicidal geriatric patients is still limited.

Material and methods

This study examines intrapsychic and psychosocial issues in suicidal geriatric inpatients. A semistructured interview concerning suicide ideation in old age was used to interview 20 randomly chosen, acutely suicidal clinically geriatric inpatients aged 60 years and older. The control group comprised 20 nonsuicidal patients.

Results

Hamilton Depression Scale 21 scores (HAMD 21; patient mean 17.3, control mean 6.1), suicidal ideation and psychiatric treatments differed significantly between the groups. In contrast to lifetime suicidal ideation, the discovery of a physical disease was the primary trigger for current suicidal ideation, followed by interactional conflicts. Patients would rather speak with family or friends than professionals about their suicidal ideation.

Conclusion

Suicidal ideation should be recognised as an important psychological problem in geriatric patients with interpersonal conflicts. Specific help and training for relatives is recommended.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Suizidalität stellt ein ernstes psychisches Gesundheitsproblem im Alter dar. Obwohl sie nicht primär von der Schwere der körperlichen Erkrankungen abhängen, bilden Suizidalität und Lebensmüdigkeit wichtige psychopathologische Entitäten in der Geriatrie. Trotz dieser Erkenntnis ist das Verständnis intrapsychischer Bedingungen der Suizidalität bei geriatrischen Patienten immer noch begrenzt.

Material und Methoden

Diese Studie untersucht intrapsychische und psychosoziale Bedingungen suizidaler geriatrischer Patienten. Es wurden 20 randomisierte, akut suizidale klinisch-geriatrische Patienten im Alter von 60 Jahren und älter und 20 nichtsuizidale Kontrollpatienten mithilfe eines semistrukturierten Interviews zu Suizidalität im Alter untersucht.

Ergebnisse

Signifikante Unterschiede zeigten sich bei Depressivität (HADS 21: Mittelwert Patienten 17,3; Mittelwert Kontrollen 6,1), bei Suizidalität und vorhergehenden psychiatrischen Behandlungen. Im Unterschied zur Suizidalität im Lebensverlauf war die Erfahrung einer körperlichen Erkrankung der Hauptauslöser für die aktuelle Suizidalität, gefolgt von interaktionellen Konflikten. Die Patienten gaben an, dass sie über ihre Suizidalität eher mit Angehörigen als mit Professionellen sprechen würden.

Schlussfolgerungen

Suizidalität sollte als ein wichtiges psychisches Problem bei geriatrischen Patienten erkannt werden, insbesondere bei interpersonellen Konflikten. Empfohlen wird eine besondere Hilfen für Angehörige.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In most European countries, suicide rates are highest among old and very old persons, particularly men. The highest rates are observed in Belarus, Hungary, Russia and the Baltic States, with Germany occupying a middle position [34]. The rate of suicide attempts remains practically stable but the severity of suicidal acts rises with age [33]. Primary motives for suicide in older persons are the loss of partner, loss of social network and loss of independence, as well as interactional conflicts [11, 16, 29, 32]. Men living alone, widowers or divorced men with limited social resources are at particular risk [7, 8, 9]. According to psychiatric nosology, unidentified and untreated depression is the main cause for suicide among the elderly [13, 30, 35, 39]. Psychological autopsy studies found affective disorders in 50–80 % of elderly suicides [22].

It has long been known that suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and suicide in the elderly—particularly among the very old [36]—are correlated with physical illnesses such as cardiac failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pain [42], seizures, urinary incontinence and cancer [41], as well as with hospitalisation [17]. It is not the severity of physical disease, but rather the psychological burden of disease and also the loss of coping strategies that lead to suicidal ideation. Many elderly people have suicidal thoughts in connection with the fear of becoming severely ill, demented or dependent [26].

Suicidal ideation is a core phenomenon in all psychiatric diseases in elderly persons. It is treated with a psychotherapeutic and, if necessary, a psychopharmacological approach. However, elderly suicidal persons are underrepresented in outpatient crisis facilities [18].

Unfortunately, there are very little data on suicidal ideation in geriatric populations. In an exploratory study, Burkhardt et al. [6] showed that about 5% of a geriatric inpatient population spoke about their wish to die with the help of professionals. These persons were very old, female, depressive and had had suicidal thoughts at previous points in their lives. The same group of researchers found that suicidal ideation is an inconstant phenomenon in geriatric patients, which may change during hospital stays [36].

The aim of this study is to gain more insight into the inner world, intrapsychic conflicts and psychosocial conditions of suicidal geriatric patients to allow development of elaborate, adequate suicide prevention strategies and treatments.

Patients and methods

Of 1363 consecutive patients, 136 were referred to the psychiatric/psychotherapeutic consultation/liaison (C/L) service (detailed description in [27]). These patients received psychodynamic psychotherapy and psychopharmacological treatment where necessary.

The first patients referred to the C/L-service on Monday morning during a 20-week period constitute the index sample. Inclusion criteria were: being suicidal or tired of life, depressive in the clinical opinion of the geriatric team and withdrawal from geriatric treatments. A single patient dropped out due to an organic paranoid syndrome.

The control sample (N = 20) was parallelized for age, gender and total Barthel Index score [19]. These patients were randomly selected during the following 20 weeks from those patients not referred to the C/L service. Inclusion criteria were: not being depressed and not having spoken about suicidal ideation or life weariness to members of the team. The three dropouts in this group were due to paranoid ideas and bad experiences with psychological professionals; an acute somatic illness and an acute crisis after receiving the diagnosis of a life-threatening disease. All study participants signed an informed consent form.

Definitions of suicidal ideation and life weariness

Suicidal ideation was defined as the entire spectrum of thoughts, emotions and acts concerning the definite suicide, as well as suicidal thoughts and behaviour [12]. Suicidal thoughts range from the idea that life is not worth living to concrete plans and circulating paranoid ideas of how to kill oneself [14]. Life weariness and death wishes are forms of suicidal ideation with less pressure to act, but they may cause severe suffering. From a psychoanalytical perspective, the predominantly conscious, accessible triggers of suicidal ideation lead to a weakening of defences. Regression to earlier forms of defence (e.g. splitting processes) and reactualization of intrapsychic conflicts about aggression and autonomy, as well as the reactualization of conflictive dyadic relationship experiences lead to perceived helplessness and pressure to act.

The structured interview

A semistructured interview (12 segments) based on former exploratory studies [28] was developed and validated [1]. It took 90–120 min to conduct and covered (1) sociodemographic data, (2) current well-being, (3) (prior) treatment experiences, (4) important relationship experiences in childhood, adulthood and at present, (5) attitudes to old age, death and dying, (6) loss of relatives, (7) current and lifetime suicidal ideation, (8) stressful life events, (9) retrospection and perspectives in life, (10) religious beliefs and political ideas, (11) daily structure and leisure time activities and (12) final interviewer rating. Each of the 12 segments started with an open question followed by deeper exploratory questions. The interview was performed in a relaxed, personal atmosphere, providing an opportunity to talk about emotional, hidden and possibly painful life themes. Each interview was audiotaped. Rating was performed by the interviewer according to previously defined rating scales. In addition, standardized diagnostic instruments were used: part of the interview is composed of the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD) [20]. International Classification of Diseases (ICD) primary diagnoses were taken from the patients’ case records.

Statistical methods

Group differences were computed with χ-square and t-tests, depending on the data level of the variables. A significance level of α = 0.05 was chosen to indicate significant differences between index and control groups. All statistical computations were performed with SPSS© 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patients and controls did not differ significantly in terms of gender, age, current marital status, level of education, professional home help, number of children, grandchildren, living with partner or years in retirement (see Tab. 1).

There were no significant differences between the index and control groups in terms of the primary diagnoses. Three patients with a psychiatric diagnosis were found in the index group (none in the control group).

There were more patients in the index group with higher HAMD scores. With a mean score of 17.3, patients showed a distinct but moderate level of depression, placing them between depressive patients in general practice (mean score = 14.7) and neurotic depressive patients (mean score = 22.89) [2].

Suicidal ideation

Of 19 patients in the index group, 12 were diagnosed as being currently suicidal. A further 4 patients had been suicidal at some point in their lives, but were not currently suicidal. No patient in the control group had attempted suicide (in their lifetime), compared to 5 patients in the index group. There were no differences between the groups in terms of suicides and suicidal ideation in the family, or in terms of stressful life events which may cause traumatisation. However, there was a trend of more experiences with the death of an important person, bombing, sexual abuse, displacement/flight and persecution in the patient group.

Patients and controls also differed significantly in terms of their experiences with treatments resulting from mental health problems during their lifetime. Patients in the index group had undergone more psychiatric and psychotherapeutic treatments (see Tab. 2).

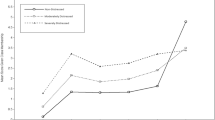

The main triggers of suicidal ideation during the course of the lifetime of suicidal patients (N = 12) were relationship conflicts, denigration, hurt and helplessness; followed by severe physical diseases. These differed from the triggers of current suicidal ideation, where severe physical diseases ranked first, followed by denigration, hurt and depression. Current suicidal fantasies were taking drugs or poison, hanging oneself and jumping from a high building. Patients would speak about their suicidal ideation first with relatives, followed by friends and acquaintances. Only a single patient mentioned choosing a professional to speak to, namely a general practitioner.

When the patients in both groups were asked to define their reasons for living,“relationships” was top of the list. “A positive attitude towards life” took second place in the control group, but, quite explicitly, not in the patient group.

There was a significant difference between the quality of the relationships experienced by members of the patient and control groups during childhood and the present time. The rating showed that patients spoke more negatively about one important person in their childhood and one person in their present life as compared to controls. There was also a significant difference between the ratings of individuals’ attitude towards their own actual age: patients spoke more negatively about their own age compared to members of the control group.

There were many persons in both groups with stressful life experiences that had probably led to traumatisation. Stressful experiences, mostly due to war, expulsion, bombing and death of an important person were reported by 12 index and 11 control patients.

Discussion

In this study the suicidal geriatric patients were more depressed compared to the control group. The triggers for their current suicidal ideation were current physical distress and the experience of social rejection. During their entire lifetime, they had undergone more psychiatric treatments and had more relationship problems. Despite these interactional problems, suicidal patients wished to speak with relatives about their suicidal ideation, rather than with a professional.

Although depression plays an important role in suicidal geriatric persons [43], the diagnosis of depression does not sufficiently explain suicidal ideation. It is, in fact, influenced by many factors, such as personality traits [21].

The experience of being severely ill is the main trigger of their current suicidal ideation [41]. But even in this group, interactional conflicts and depression were the subsequent factors leading to suicide [40]. This leads to the hypothesis that suicidal geriatric patients comprise a group that have experienced mental disorders and relationship problems in their lives, which are reactivated by current experiences of physical distress and subsequent disabilities and restrictions.

The finding that narratives of an important person in childhood and of a currently important person were both rated significantly more negatively than in the control group indicate that even in old age, the experience of a currently important relationship is influenced by relationship experiences during childhood and adolescence. This finding has the limitation that even though depressed patients are able to produce undistorted memories [4], the debate concerning false memories makes it obvious that there is no absolute certainty regarding childhood memories [37]. Therefore, any correlations between early and current relationships and how these are perceived must still be viewed as hypothetical.

It is important to mention the high rate of stressful life experiences in both groups (patients: 12/19, controls: 11/17). This is a particular issue among elderly persons in northern Germany, many of whom have experienced displacement and bombing, as well as other war-related traumas like rape. Radebold [31], Brähler et al. [5] and Strauss et al. [38] stressed the influence of these experiences on the development of psychiatric disorders, particularly panic disorders, depression and poor health perception.

Our data suggest that the important triggers of suicidal ideation during lifetime are relationship problems and the experience of distress in important relationships. These findings are in line with the correlation of depression and family discord with suicide found by Waern et al. [40]. It has to be mentioned that, in spite of their problems in important relationships, the suicidal patients preferred to speak to relatives and friends about their suicidal ideation and stated that relationships were their main reason for staying alive. This finding may be an indicator of the relevance of probable lifelong interpersonal and intrapsychic conflicts—a notion that is well-described in depressive psychopathology—in this group of patients. It was Freud [19] who developed a psychopathological model of suicidal ideation in which the suicidal person suffers from an intrapsychic aggression conflict. In this conflicting inner state, the patient experiences both a high need for and dependency on an important person, while at the same time harbouring feelings of hate and aggression toward that same person. Later, psychoanalytic clinicians described several suicidal aggression conflicts that may lead to suicidal ideation, in which the suicidal person feels deeply bound to the object, while simultaneously feeling distress, anger, hate and frustration [23]. Such conflicts can be very relevant in caring and nursing relationships—with both relatives and professionals—in functionally distressed patients with multiple morbidities. Recognizing and understanding these conflicts may help professionals to provide sensitive care and enter into helpful communication about the patients’ relationship problems.

Some important limitations need to be addressed. Firstly, the sample size was not calculated in advance and the sample is not representative of all geriatric patients. The rater was not blinded and not all suicidal patients were examined. Patients who did not show any signs of depression and did not communicate their suicidal thoughts to anybody could not be detected. In fact, during the research period there was one suicide by a patient who had not been previously recognized as being suicidal (and who was also not in the control group) [24].

All findings from this study are exploratory. Since suicidal ideation is hard to examine with empirical methods because of its sometimes latent, disguised and neglected character, and because suicidal ideation is a comparatively rare phenomenon, studies with higher degrees of evidence about the intrapsychic situation of these patients will be hard to conduct.

Conclusion and recommendations for clinical practice

In geriatric medicine, suicidal ideation should be recognized as an important psychological problem. Many complaints about physical disabilities may occur on a background of psychological problems and interpersonal conflicts representing lifelong dysfunctional relationship patterns, which may also influence the actual experience of disease and disablement in old age. Although the recommendation to be aware of suicidal ideation in clinical work sounds simple, there are multiple factors working against this. The main problem is that suicidal ideation makes professionals feel uneasy, even more responsible, anxious, annoyed and concerned, which may translate into avoidance of the issue. In patients who are psychologically demanding and engage in destructive interactions—thereby hindering treatment—it seems important to gain a better understanding of their inner conflicts. This particularly applies to matters regarding dependency and autonomy and should be addressed on the basis of a patient’s biography. For suicide prevention it seems to be important to approach the family of suicidal elderly persons and to offer family members help in speaking about suicidal ideation with their elderly relatives [39]. It is also important to reach other friends and relatives, as well as to raise public awareness. This can be achieved by individual counselling, training sessions and public dialogue. Further research is needed to improve the understanding of the interactional patterns of elderly suicidal persons—particularly when they are physically ill—and to gain a deeper understanding of the difference between suicidal ideation, life weariness and the wish to die among this group of patients.

References

Altenhöfer A, Lindner R, Fiedler G et al (2008) Profile des Rückzugs – Suizidalität bei Älteren. Psychotherapie im Alter 5:225–240

AMDP & CIPS (1990) Ratingscales for psychiatry. Beltz Test, Weinheim

Barnow S, Linden M (2000) Epidemiology and psychiatric comorbidity of suicidal ideation among the elderly. Crisis 21:171–180

Bifulco A, Brown GW, Harris TO (1994) Childhood experience of care and abuse (CECA): a retrospective interview measure. J Child Psychol Psychiat 35:1419–1435

Brähler E, Decker O, Radebold H (2004) Ausgebombt, vertrieben, vaterlos – Langzeitfolgen bei den Geburtsjahrgängen 1930–1945 in Deutschland. In: Radebold H (Hrsg) Kindheiten im II. Weltkrieg und ihre Folgen. Psychosozial-Verlag, Gießen, pp 111–136

Burkhardt H, Sperling U, Gladisch R, Kruse A (2003) Todesverlangen – Ergebnisse einer Pilotstudie mit geriatrischen Akutpatienten. Z Gerontol Geriat 36:392–400

Canetto SS (1991) Gender roles, suicide attempts and substance abuse. J Psychol 125:605–620

Canetto SS (1994) Gender issues in the treatment of suicidal behavior. Death Studies 18:513–327

Canetto SS, Lester D (1995) Gender and the primary prevention in the treatment of suicidal behavior. Suicide Life Threat Behav 25:58–69

Carney SS (1994) Suicide over 60: the San Diego study. J Am Geriatr Soc 42:174–180

Cattel H (2000) Suicide in the elderly. Adv Psychiatr Treat 6:102–108

Chiles JA, Strosahl KD (1995) The suicidal patient. American Psychiatric Press, Washington

Conwell Y, Thompson C (2008) Suicidal behavior in elders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 31:333–356

Diekstra RFW, Garnefski N (1995) On the nature, magnitude, and causality of suicidal Behaviors: an international perspective. Suicide Life Threat Behav 25:36–57

Draper B (1996) Attempted suicide in old age. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 11:25–30

Duberstein PR, Conwell Y, Conner KR et al (2004) Suicide at 50 years of age and older: perceived physical illness, family discord and financial strain. Psychol Med 34:137–146

Erlangsen A, Vach W, Jeune B (2005) The effect of hospitalization with medical illnesses on the suicide risk in the oldest old: a poulation-based register study. J Am Geriatr Soc 53:771–776

Erlemeier N (2001) Suizidalität und Suizidprävention im Alter. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart

Freud S (1917) Trauer und Melancholie. Gesamtwerk, Vol 10. Fischer, Frankfurt, pp 427–446

Hamilton M (1960) A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 23:56–62

Heisel MJ, Duberstein PR, Conner KR et al (2006) Personality and reports of suicide ideation among depressed adults 50 years of age and older. J Affect Disord 90:75–180

Henriksson MM, Isometsä ET, Hietanen PS et al (1995) Mental disorders in cancer suicides. J Affect Disord 36:11–20

Lindner R (2006) Suicidal ideation in men in psychodynamic psychotherapy. Psychoanal Psychother 20:197–217

Lindner R (2009) Aggression und Rückzug bei Suizidalität im Alter. Eine Kasuistik. Suizidprophylaxe 36:42–46

Lindner R, Altenhöfer A, Fiedler G, Götze P (2007) Suicidal ideation in later life. In: Briggs S, Lemma A, Crouch W (Hrsg) Relating to self-harm and suicide. Psychoanalytic perspectives on practice, theory and prevention. Routledge, New York, pp 187–197

Lindner R, Altenhöfer A, Fiedler G et al (2008) Suizidalität im Alter. Psychotherapie im Dialog 9:48–52

Lindner R, Foerster R, Renteln-Kruse W von (2013) Idealtypische Interaktionsmuster psychosomatischer Patienten in stationär-geriatrischer Behandlung. Z Gerontol Geriatr 46:441–448

Mahoney FI, Barthel D (1965) Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J 14:56–61

Mellqvist Fässberg M, Orden KA van, Duberstein P et al (2012) A systematic review of social factors and suicidal behavior in older adulthood. Int J Environ Res Public Health 9:722–745

O’Connell H, Chin AV, Cunningham C, Lawlor BA (2004) Recent developments: suicide in older people. Br Med J 329:895–899

Radebold H (2004) Kriegsbeschädigte Kindheiten (1928–29 bis 1945–48) Kenntnis- und Forschungsstand. In: Radebold H (Hrsg) Kindheiten im II. Weltkrieg und ihre Folgen. Psychosozial-Verlag, Gießen, pp 17–29

Rubenowitz E, Waern M, Wilhelmson K, Allebeck P (2001) Life events and psychosocial factors in elderly suicides—a case-control study. Psychol Med 31:1193–1202

Schmidtke A, Sell R, Löhr C (2008) Epidemiologie von Suizidalität im Alter. Z Gerontol Geriatr 41:3–13

Schmidtke A, Sell R, Löhr C et al (2009) Epidemiologie und Demographie des Alterssuizids. Suizidprophylaxe 36:12–20

Skoog I, Aevarsson Ö, Beskow J et al (1996) Suicidal feelings in a population sample of nondemented 85-year-olds. Am J Psychiatry 153:1015–1020

Sperling U, Thüler C, Burkhardt H, Gladisch R (2009) Äußerungen eines Todesverlangens – Suizidalität in einer geriatrischen Population. Suizidprophylaxe 36:29–35

Stoffels H, Ernst C (2002) Erinnerung und Pseudoerinnerung. Über die Sehnsucht, Traumaopfer zu sein. Nervenarzt 73:445–451

Strauss K, Dapp U, Anders J et al (2011) Range and specificity of war-related trauma to posttraumatic stress; depression and general health perception: displaced former World War II children in late life. J Affect Disord 28:267–276

Waern M, Beskow J, Runeson B, Skoog I (1999) Suicidal feelings in the last year of life in elderly people who commit suicide. Lancet 354:917–918

Waern M, Rubenowitz E, Wilhelmson K (2003) Predictors of suicide in the old elderly. Gerontology 49:328–334

Wedler H (2009) Suizidalität und körperliche Erkrankung im höheren Lebensalter. Suizidprophylaxe 36:25–29

Wedler H (2012) Schmerz und Suizidalität. Suizidprophylaxe 39:64–68

Zietemann V, Zietemann P, Weitkunat R, Kwetkat A (2007) Depressionshäufigkeit in Abhängigkeit von verschiedenen Erkrankungen bei geriatrischen Patienten. Nervenarzt 78:657–664

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Forschungskolleg Geriatrie, Robert Bosch Stiftung, Stuttgart.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Conflict of interest. R. Lindner, R. Foerster and W. von Renteln-Kruse state that there are no conflicts of interest.

All studies on humans described in the present manuscript were carried out with the approval of the responsible ethics committee and in accordance with national law and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (in its current, revised form). Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lindner, R., Foerster, R. & von Renteln-Kruse, W. Physical distress and relationship problems. Z Gerontol Geriat 47, 502–507 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-013-0563-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-013-0563-z