Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this meta-analysis was to compare high inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) ligation (HL) with low IMA ligation (LL) for the treatment of colorectal cancer and to evaluate the lymph node yield, survival benefit, and safety of these surgeries.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and China Biomedical Literature Database (CBM) were systematically searched for relevant articles that compared HL and LL for sigmoid or rectal cancer. We calculated the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous outcomes and the weighted mean difference (WMD) for continuous outcomes.

Results

In total, 30 studies were included in this analysis. There were significantly higher odds of anastomotic leakage and urethral dysfunction in patients treated with HL compared to those treated with LL (OR = 1.29; 95% CI = 1.08 to 1.55; OR = 2.45; 95% CI = 1.39 to 4.33, respectively). There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of the total number of harvested lymph nodes, the number of harvested lymph nodes around root of the IMA, local recurrence rate, and operation time. Further, no statistically significant group differences in 5-year overall survival rates and 5-year disease-free survival rates were detected among all patients nor among subgroups of stage II patients and stage III patients, respectively.

Conclusions

LL can achieve equivalent lymph node yield to HL, and both procedures have similar survival benefits. However, LL is associated with a lower incidence of leakage and urethral dysfunction. Thus, LL is recommended for colorectal cancer surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related death, with approximately 880,792 deaths and about 1,849,518 newly diagnosed cases in 2018 [1]. Both total mesorectal excision (TME) and complete mesocolic excision (CME) are reported to reduce local recurrence and improve survival rates in patients with rectal and colorectal cancer. Thus, these techniques have gradually became the standard techniques used in colorectal surgery [2, 3].

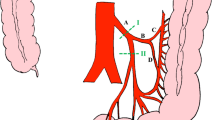

In colorectal surgery, the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) can be ligated at the origin of the aorta (high ligation) or distal to the origin of the left colic artery (low ligation) [4]. There is considerable controversy surrounding the use of these two techniques [5, 6]. Some researchers recommend high IMA ligation (HL), arguing that this technique results in more radical lymph node excision and improved node harvest [4]. However, it is also hypothesized that reducing blood flow to the distal colon may lead to increased risk of anastomotic leakage (AL) and may sacrifice the autonomic nerves around the origin of the IMA [7]. In contrast, the low IMA ligation (LL) technique maintains adequate blood supply to the colon proximal to the anastomotic stoma [8]. Further, there is little to no risk of injury to the autonomic nerve with this technique; however, it may result in slightly less radical clearance of nodes [9].

High-quality meta-analysis has been increasingly regarded as one of the key tools for obtaining evidence [10, 11]. Although there have been several meta-analyses examining which technique is better, it is important to note that the conclusions of these studies remain controversial and autonomic nerve damage has not been examined as an outcome [5, 6, 12,13,14]. Further, there have been several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and retrospective cohort studies published in recent years examining the oncologic outcomes and safety of HL and LL; these have not been included in the published meta-analyses to date. Additionally, several studies have reported that HL may improve survival rate in patients at certain disease stages [15, 16]; the available meta-analyses have not addressed this finding. Thus, herein we performed a comprehensive meta-analysis including recently published studies to compare HL with LL. The current meta-analysis evaluated lymph node yield, survival benefit, and safety of each technique and further analyzed survival benefits in patients at different disease stages (stage II and stage III).

Methods

Search strategy

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [17].

PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and the China Biomedical Literature Database (CBM) were comprehensively searched by two independent reviewers for relevant articles comparing HL and LL techniques in sigmoid or rectal cancer patients; the initial database searches encompassed studies published from the inception date of each database to November 2018. There were no language restrictions placed on these database searches. A final search was performed in March 2019, to check for any additional potentially eligible studies published since the initial database searches. Database-specific subject headings, known as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, and free texts terms were used to search for and identify potentially eligible studies; complete search algorithms for each database are available in Appendix 1. Reference lists of all retrieved articles were manually searched to identify additional studies. In order to ensure all relevant studies were identified, no restrictions were placed on the date of publication or regional state.

Study selection

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for our study were as follows: (1) patients definitely diagnosed with sigmoid or rectal cancer by enhanced computed tomography, colonoscopy, and pathological biopsy assessment; (2) study compares the initial therapy effects of HL and LL of the IMA for the treatment of sigmoid or rectal cancer, regardless of the etiology of colorectal cancer and differences in surgical approaches (open or laparoscopic); (3) no previous or simultaneous malignancies were detected in the patients before surgery; and (4) the study reports on at least one of the outcome measures mentioned below.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) abstracts, letters, editorials and expert opinions, reviews without original data, case reports, and studies lacking control groups and (2) massive invasion of cancer into adjacent organs that could not be resected.

Data extraction

Data from each study reporting the outcomes of interest were extracted by two independent reviewers. The relevant data included first author, publication year, country, type of study, gender, age, cases of patients, patient recruitment period, BMI, follow-up duration, and patient clinical outcomes. Any discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion to reach agreement; if an agreement between the two reviewers could not be reached, a third person was involved.

The patient clinical outcomes were categorized into one of the following three categories: lymph node yield, survival benefit, and safety. Lymph node yield outcomes included the total number of harvested lymph nodes and the number of harvested lymph nodes around the root of the IMA. Survival benefit outcomes included 5-year overall survival (OS) rates and 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) rates for all patients, as well as for stage II patients and stage III patients, respectively. The local recurrence rate was also included in this category. The safety outcomes included anastomotic leakage, urethral dysfunction, and operation time.

Quality assessment

All studies were independently assessed by two investigators for quality and validity using two scales: the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for the six randomized controlled trials (RCTs) included in the review and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for the remaining cohort studies and case-control studies [18, 19]. The results of this assessment are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Disagreements in the quality assessment were resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 14 (StataCorp LP). We used random-effects models to analyze data because it thinks over the almost inevitable natural variation inherent between studies, especially in the field of surgical research [47]. We then calculated the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous outcomes and the weighted mean difference (WMD) for continuous outcomes. Meanwhile, we explored statistical heterogeneity using the I2 test statistic. A sensitive analysis was subsequently conducted by eliminating each study in the analysis at each turn. A potential publication bias was evaluated by visually inspecting the Begg’s funnel plots in which the log OR is plotted against the standard error (SE). A P value of less than (<) 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Subgroup analysis

Recently, a technique involving LL with apical lymph node dissection around the root of the IMA to achieve D3 lymph node dissection has been widely used in clinical settings, especially in Asian countries [48]. This approach is different from standard LL (i.e., LL procedure without lymph node dissection around the IMA) [37]. Our review identified studies of standard LL as well as LL with D3 lymph node dissection, which was defined for the purpose of this review as modified LL. Thus, we performed a subgroup analysis based on detailed data regarding the total number of lymph nodes harvested and the operative time in patients with these two LL techniques.

Results

Description of study selection

The initial search criteria captured 475 citations, and an additional 7 studies were identified by manually examining the reference lists of the identified studies. In total, 34 duplicate studies were removed. Then, the titles and abstracts of the remaining 448 records were screened for the inclusion criteria; this resulted in the exclusion of 410 studies. The full texts of the remaining 38 records were then read. Thirty of these studies were deemed to satisfy the inclusion criteria and were retained for analysis [4, 7, 9, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. The PRISMA flow diagram of this process is shown in Fig. 1 and the study characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Lymph node yield outcomes

Total number of harvested lymph nodes

The meta-analysis of 19 trials reporting this data indicated that there was no significant difference between the two groups (WMD = 0.64; 95% CI = − 0.65 to 1.93; P = 0.33), with certain heterogeneity (Fig. 2). The subgroup analysis did not reveal any significant difference between the group treated with modified LL and the group treated with HL (WMD = − 0.15; 95% CI = − 1.64 to 1.34; P = 0.84). However, the total number of harvested lymph nodes was significantly less than HL when standard LL was performed (WMD = 2.69; 95% CI = 0.53 to 4.85; P = 0.01) (Fig. 2).

The number of harvested lymph nodes around the root of the IMA

The meta-analysis of eight trials reporting this data showed no significant difference between the two groups (WMD = − 0.11; 95% CI = − 0.45 to 0.24; P = 0.54), with certain statistical heterogeneity (Fig. 3).

Survival benefit outcomes

Five-year OS

The meta-analysis showed no statistical difference between the HL group and LL group (OR = 1.07; 95% CI = 0.93 to 1.23; P = 0.34), with no evidence of significant heterogeneity. For stage II patients and stage III patients, the pooled results also showed no statistical difference between the two groups (OR = 2.29; 95% CI = 0.83 to 6.33; P = 0.11; OR = 0.81; 95% CI = 0.61 to 1.08; P = 0.15, respectively) (Fig. 4).

Five-year DFS

The meta-analysis showed no significant difference in 5-year DFS between the HL and LL groups (OR = 0.98; 95% CI = 0.69 to 1.40; P = 0.91), with no evidence of significant heterogeneity. There was also no significant difference between the two groups for stage II and stage III patients (OR = 1.23; 95% CI = 0.58 to 2.58; P = 0.59; OR = 0.72; 95% CI = 0.36 to 1.42; P = 0.34, respectively) (Fig. 5).

Local recurrence rates

The meta-analysis of nine trials reporting this data showed no statistically significant difference between the HL and LL groups (OR = 0.95; 95% CI = 0.67 to 1.33; P = 0.75), with no evidence of significant heterogeneity (Fig. 6).

Safety outcomes

Anastomotic leakage

The meta-analysis of 22 trials reporting this data revealed a significant difference between the two groups (OR = 1.29; 95% CI = 1.08 to 1.55; P = 0.005), whereby LL-treated patients had a lower incidence of anastomotic leakage compared to HL-treated patients; there was no evidence of significant heterogeneity (Fig. 7).

Urinary dysfunction

The meta-analysis of five trials reporting this data indicated that the incidence of urinary dysfunction was significantly lower in the LL-treated group (OR = 2.45; 95% CI = 1.39 to 4.33; P = 0.002) compared to the HL group; there was no evidence of significant heterogeneity (Fig. 8).

Operation time

The meta-analysis of 13 trials reporting this data revealed no significant difference between the HL and LL groups (WMD = − 1.96; 95% CI = − 8.27 to − 4.34; P = 0.54), with certain heterogeneity (Fig. 9). The results of subgroup analysis showed no significant difference between standard low IMA ligation and HL (WMD = − 6.04; 95% CI = − 14.14 to − 26.23; P = 0.56) nor between modified low IMA ligation and HL (WMD = − 5.32; 95% CI = − 11.44 to 0.81; P = 0.09) (Fig. 9).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis by investigating the influence of a single study on the overall pooled estimates; this was achieved by eliminating one study at a time and repeating the analyses. When we excluded the study of Zhou et al., the recalculated results showed that the total number of harvested lymph nodes in the HL group was greater than the LL group (WMD = 1.18; 95% CI = 0.11 to 2.25; P = 0.03; I2 = 82%); this is in contrast to the primary results including all studies (WMD = 0.64; 95% CI = − 0.65 to 1.93; P = 0.33; I2 = 89%). However, for the subgroup of patients who received modified LL, there remained no significant difference in the total number of harvested lymph nodes, compared to the HL group (WMD = 0.64; 95% CI = − 0.55 to 1.83; P = 0.29; I2 = 88%). It is clear that the heterogeneity did not change significantly when the study by Zhou et al. was excluded (total results △I2 = 6% and subgroup of modified LL results △I2 = 5%). Therefore, the study by Zhou et al. is not the source of heterogeneity. Rather, wide inter-individual variations in both patients (anatomy) and surgeons (surgical technique) may have contributed to this heterogeneity. Thus, we did not exclude the study of Zhou et al. and conclude that there was no significant difference in the total number of harvested lymph nodes between the two groups.

Assessment of publication Bias

We only analyzed publication bias for outcomes included in 10 or more studies [18]. After viewing the funnel plots and Egger’s tests, it was concluded that none of the four outcomes showed publication bias.

Discussion

Lymph node dissection is considered to be essential in oncological colorectal surgery [24], and several researchers have discussed the importance of radical lymph node dissection up to the root of the IMA [49]. One widely accepted advantage of HL is that it allows en bloc removal of additional nodes at and around the root of the IMA; thus, apical lymph nodes may be retrieved, possibly resulting in improved tumor staging and oncological outcomes [31]. However, in the current study, we did no observe any advantage of HL; the number of harvested lymph nodes, both in terms of the total number and the number around root of the IMA, was not statistically different from the LL group. We also conducted subgroup analysis to compare the different LL techniques. The total number of lymph nodes harvested in the standard LL group was significantly less than in the HL group, which appears to reflect an advantage of HL. However, there was no significant difference between the modified LL group and the HL group. This modified LL technique was initially used in clinical practice in Japan and was described by Japanese researchers [30, 37]. Since then, the number of published cases has increased rapidly. The feasibility and oncological safety of this technique have been confirmed in previous studies [37, 42]. However, it has been reported that this technique requires a longer operative time due to the increased difficulty of the surgery [26]. This is in contrast to the findings of the current study where no statistically significant difference in operation time was found between the modified LL group and the HL group. Recently, Sekimoto et al. reported an approach that can overcome the technical difficulties of the modified LL technique through emphasis of dissection of the layer between the vascular sheath and the artery; this is because there are only a few small vessels in this region [26]. Although this study was only a single center study, it provides support for our pooled results.

According to a previous study, the 5-year OS rate in patients with IMA root nodal metastasis is poor compared with patients without metastasis [29]. Further, many studies have reported that HL does not improve survival benefit because steady rates of metastasis occur at the IMA root nodes with or without HL [29, 50]. Taken together, these findings demonstrate a relationship between the metastatic rate of the IMA root nodes and the survival rate, suggesting that any survival benefit relies on the scope of the lymphadenectomy and whether or not the IMA is ligated. Furthermore, Titu et al. argued that the status of the lymph nodes around the IMA root is the most important determinant of DFS [27]. Therefore, it is not surprising that we observed similar 5-year OS rates and 5-year DFS rate between the two groups because the total numbers of lymph nodes harvested and the number of harvested lymph nodes around the IMA root were not significantly different between the HL and LL groups. And, the metastasis rate of the IMA root nodes is stable and low [29].

While the results of the current study indicate that HL does not improve the 5-year survival of patients with rectal or sigmoid cancer, specifically, as mentioned in the “Introduction,” HL may provide survival benefit to patients at certain disease stages. Therefore, we further conducted analysis of the 5-year OS rate and DFS rate in patients with stage II and stage III disease, respectively. In performing this analysis, we also aimed to further explain our finding of no difference in survival between the HL group and LL group from another perspective besides lymph node yield. However, we found no difference in survival between the two IMA ligation techniques among stage II and stage III patients, respectively, though it should be noted that stage migration may confound these results [32]. These findings are inconsistent with the findings mentioned above and also contradict a recent meta-analysis which reported that HL should be recommended for suspected advanced stage patients or those at high risk of IMA-positive metastatic lymph nodes [13]. This recommendation was based on a pooled result showing that the 5-year OS rate was improved in stage III patients with HL relative to those with LL.

Stage II patients did not have any lymphatic metastasis [51]; thus, complete resection of the tumor could be accomplished as long as adequate circumferential and distal margins were ensured on the basis of TME or CME [27]. Leek et al. reported that LL can achieve equivalent distal margin length and oncologically appropriate mean proximal margin length compared to HL [42]; this finding could explain the similar survival rates observed in the current study.

Lymph node metastasis is an important factor affecting the prognosis of colorectal cancer patients. For stage III patients, there are a number of potential factors accounting for the similar survival rate observed between the HL and LL groups. Primarily, although lymphatic drainage of rectal and rectosigmoid cancers is still thought to occur predominantly along the IMA, other lymphatic pathways do exist and may confound the assessment of HL [20]. One typical example is the presence of lateral lymphatic drainage routes of tumors of the lower third of the rectum [20]. Secondly, lymph node dissection with ligation of drainage vessels is the standard procedure in colonic radical surgery [24]; all suspected positive lymph nodes beyond the origin of the feeding vessel should be biopsied or removed, or the scope of resection should be extended to include the suspicious lymph nodes. Nonetheless, skip metastases may still be present in 5% of cases [32]. Grinnell et al. reported that once neoplasms have invaded these high lymph nodes, it is likely that the cancer is widespread [52]. Kawamura et al. argued that extensive lymphadenectomy does not increase DFS in patients with lymph nodal involvement and it is likely that the unresected nodes will contain malignant cells [24].

Several recently published meta-analyses have compared HL and LL in terms of postoperative safety; however, the incidence of AL between the two groups remains controversial. Further, outcomes for the assessment of autonomic nerve function injury have not been reported in previous meta-analyses [5, 6, 12]. Therefore, in our study, we focused on the postoperative safety outcomes of AL and UD.

AL is a very serious postoperative complication that occurs in patients who have undergone radical surgery. The incidence of AL is reported to be approximately 10% [34]. Rutegard et al. argued that with the advent of the TME technique, complications such as AL have been increasing in frequency [36]. Further, AL is reported to be associated with subsequent local recurrence and distant metastasis as well as operative mortality rate [34]. Therefore, reducing the likelihood of AL is crucial for good surgical outcomes. It is well known that there are many risk factors for AL [36]; however, blood supply and anastomotic tension are most focused by surgeons due to an anastomosis free of tension with a good blood supply is of crucial importance in radical resection of colorectal cancer [9]. In our study, the pooled result showed that the incidence of AL was significantly lower in the LL group as compared with the HL group. This finding is consistent with two meta-analyses recently published by Fan et al. and Zeng et al. [5, 6]. However, our findings are in contrast to those of Yang et al. [12].

The colon below the root of the IMA is perfused by both the IMA and the marginal artery (MA) of Drummond emanating from the middle colic artery (MVA) [33]. Some studies suggest that the MA is adequate for providing blood supply to the proximal colon in patients who have undergone HL [33, 36]. However, because the left colic artery (LCA) and its ascending branch are ligated when HL is performed, there is no longer a second pathway for the perfusion of the colon proximal to anastomosis. Therefore, perfusion of the proximal loops is greatly affected [33]. Dworkin et al. and Allen Mersh et al. assessed the affection using Doppler flowmetry and found that HL significantly reduces perfusion of the proximal limb of the colon [53]. The decrease in proximal intestinal perfusion blood flow may lead to the incidence of anastomotic ischemia. If the affected proximal limb has evidence of ischemia, the surgeon usually chooses to perform an additional colectomy [31]. This would increase the risks associated with the surgery and the incidence of AL. From an anatomical point of view, the left branch of the MCA and the ascending branch of the LCA form anastomotic branches near the splenic flexure through the Riolan arc, but anastomosis in this area is usually thin and is absent in 5% of cases [38]; this undoubtedly increases the incidence of AL in HL-treated patients. On the other hand, several studies that have examined the area of the descending colon have reported that the quality of the MA between the final two branches of the LCA may be poor; thus, the final divisions must be carefully performed to support the MA in this region [21]. Further, given that laparoscopic techniques are widely used for surgery, bipolar electrosurgery instruments or high-power ultrasonic dissection devices might cause damage to the MA leading to a lack of blood supply to the anastomosis [28]. This would also increase the risk of AL in patients with HL. While our study did not include an outcome reflecting anastomosis tension, many researchers argue that LL offers sufficient length to create tension-free anastomosis [36] and Bonnet et al. insisted that the additional gain in colonic length produced by HL is only small [42].

Autonomic nerve injury is another common postoperative complication of colon cancer surgery. Based on the primary studies evaluated in the current meta-analysis, we can only analyze postoperative UD. The pooled result indicated that the incidence of UD was significantly lower in the LL group. Anatomically, the lumbar splanchnic nerves associated with bladder function are distributed at the origin of the IMA [29]. Therefore, the reduced occurrence of UD in the LL group may be due to the protection of autonomic nerves from injury.

Our meta-analysis has several advantages over the available published meta-analyses. First, we included a large number of studies. In particular, we included several RCTs and retrospective cohort studies that have been recently published and were not captured by previous meta-analyses. Second, our meta-analysis included more than 11,000 patients from nine different countries, allowing us to obtain results that are broader in scope and richer in meaning. Finally, we further performed analysis of 5-year OS rate and DFS rate in stage II and stage III patients in order to assess whether there is a difference between the two techniques in patients at different disease stages.

Despite these advantages, the pooled results of this meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution for several reasons. First, the literature review retrieved 30 eligible studies; six of these were RCTs and the remaining 24 studies were retrospective observational studies. The observational studies that may lead to the overall level of clinical evidence obtained here are relatively low [54]. Second, the lack of a formal definition of anastomotic leakage may attenuate associations between level of ligation and leakage [31]. Third, we analyzed the total number of harvested lymph nodes and the operative time based on the two different LL techniques; however, the two LL techniques could not be analyzed separately with respect to the other outcomes examined in our study due to a lack of available data. Finally, as Betrand et al. [55] and Murono et al. [48] showed in their respective study, there is inter-individual variation in the anatomy of the division of the branches of the IMA. Due to individual differences between patients (anatomy) and surgeons (surgical techniques), it is difficult, if not impossible, to identically reproduce a surgical procedure. Therefore, some outcomes of our meta-analysis exhibited high heterogeneity, which may affect the quality of evidence to some extent.

Conclusion

In conclusion, LL can achieve equivalent lymph node yield and survival benefit as compared to HL and is associated with a lower incidence of AL and UD. Another advantage of LL is that surgery on the residual colon can be performed since the LCA is preserved. For patients with recurrent ascending or transverse colon tumors after surgery for rectal or sigmoid cancer, the left transverse colon is more likely to be able to be retained because there is blood flow to the LCA [37]. Thus, based on the current available evidence, LL is recommended for colorectal cancer surgery regardless of the stage of the tumor. High-quality RCTs that investigate the efficiency and safety of the two techniques, especially with respect to modified LL, are needed to provide more reliable evidence and validate these recommendations.

References

Organization WH (2018) International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/10_8_9-Colorectum-fact-sheet.pdf

Hohenberger W, Weber K, Matzel K, Papadopoulos T, Merkel S (2009) Standardized surgery for colonic cancer: complete mesocolic excision and central ligation—technical notes and outcome. Color Dis: Off J Assoc Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland 11:354–364 discussion 364-355

Heald RJ, Husband EM, Ryall RD (1982) The mesorectum in rectal cancer surgery—the clue to pelvic recurrence? Br J Surg 69:613–616

Fujii S, Ishibe A, Ota M, Watanabe K, Watanabe J, Kunisaki C, Endo I (2018) Short-term results of a randomized study between high tie and low tie inferior mesenteric artery ligation in laparoscopic rectal anterior resection: sub analysis of HTLT (high-tie vs low-tie) study. Surgical Endoscopy and Other Interventional Techniques Conference: 16th World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery United States, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6119-y

Fan Y-C, Ning F-L, Zhang C-D, Dai D-Q (2018) Preservation versus non-preservation of left colic artery in sigmoid and rectal cancer surgery: a meta-analysis. Int J Surg 52:277–285

Zeng JS, Su GQ (2018) High ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery during sigmoid colon and rectal cancer surgery increases the risk of anastomotic leakage: a meta-analysis. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 16(1 Article Number):157

Matsuda K, Hotta T, Takifuji K, Yokoyama S, Oku Y, Watanabe T, Mitani Y, Ieda J, Mizumoto Y, Yamaue H (2015) Randomized clinical trial of defaecatory function after anterior resection for rectal cancer with high versus low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery. Br J Surg 102:501–508

Ikeda Y, Shimabukuro R, Saitsu H, Saku M, Maehara Y (2007) Influence of prophylactic apical node dissection of the inferior mesenteric artery on prognosis of colorectal cancer. Hepato-gastroenterology 54:1985–1987

Corder AP, Karanjia ND, Williams JD, Heald RJ (1992) Flush aortic tie versus selective preservation of the ascending left colic artery in low anterior resection for rectal-carcinoma. Br J Surg 79:680–682

Tian J, Zhang J, Ge L, Yang K, Song F (2017) The methodological and reporting quality of systematic reviews from China and the USA are similar. J Clin Epidemiol 85:50–58

Wang X, Chen Y, Yao L, Zhou Q, Wu Q, Estill J, Wang Q, Yang K, Norris SL (2018) Reporting of declarations and conflicts of interest in WHO guidelines can be further improved. J Clin Epidemiol 98:1–8

Yang Y, Wang G, He J, Zhang J, Xi J, Wang F (2018) High tie versus low tie of the inferior mesenteric artery in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Surg 52:20–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.12.030

Singh D, Luo J, X-t L, Ma Z, Cheng H, Yu Y, Yang L, Zhou Z-G (2017) The long-term survival benefits of high and low ligation of inferior mesenteric artery in colorectal cancer surgery: a review and meta-analysis. Medicine 96:e8520

Chen SC, Song XM, Chen ZH, Li MZ, He YL, Zhan WH (2010) Role of different ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in sigmoid colon or rectal cancer surgery: a meta-analysis. Chin J Gastrointes Surg 9:674–677

Kanemitsu Y, Hirai T, Komori K, Kato T (2006) Survival benefit of high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in sigmoid colon or rectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg 93:609–615

Hida J, Okuno K, Yasutomi M, Yoshifuji T, Matsuzaki T, Uchida T, Ishimaru E, Tokoro T, Shiozaki H (2005) Number versus distribution in classifying regional lymph node metastases from colon cancer. J Am Coll Surg 201:217–222

Ge L, Tian JH, Li YN, Pan JX, Li G, Wei D, Xing X, Pan B, Chen YL, Song FJ, Yang KH (2018) Association between prospective registration and overall reporting and methodological quality of systematic reviews: a meta-epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol 93:45–55

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA (2011) The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 343:d5928

Xiu-xia L, Ya Z, Yao-long C, Ke-hu Y, Zong-jiu Z (2015) The reporting characteristics and methodological quality of Cochrane reviews about health policy research. Health policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 119:503-510

Pezim ME, Nicholls RJ (1984) Survival after high or low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery during curative surgery for rectal cancer. Ann Surg 200:729–733

Surtees P, Ritchiei JK, Phillips RKS (1990) High versus low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in rectal cancer. Br J Surg 77:618–621

Gao YF, Jiang JB, Sun RX, Tu-CL (1999) A clinical assessment for using high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery and extensive lymphadenectomy in advanced rectal cancer. Chin J Gastrointest Surg 2:100–103

Chen CQ, Zhan WH, Wang P, Chen ZX, Huang YH, He YL, Lan P (2000) High ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery affect patient prognosis following resection of rectal cancer. Chin J Cancer 19:918–921

Kawamura YJ, Umetani N, Sunami E, Watanabe T, Masaki T, Muto T (2000) Effect of high ligation on the long-term result of patients with operable colon cancer, particularly those with limited nodal involvement. Eur J Surg 166:803–808

Komen N, Slieker J, Kort P, Wilt JHW, Harst E, Coene P, Gosselink M, Tetteroo G, Beek E, Toom R, Bockel W, Verhoef C, Lange J (2011) High tie versus low tie in rectal surgery: comparison of anastomotic perfusion. Int J Color Dis 26:1075–1078

Sekimoto M, Takemasa I, Mizushima T, Ikeda M, Yamamoto H, Doki Y, Mori M (2011) Laparoscopic lymph node dissection around the inferior mesenteric artery with preservation of the left colic artery. Surg Endosc Other Interv Tech 25:861–866

Rutegard M, Hemmingsson O, Matthiessen P, Rutegard J (2012) High tie in anterior resection for rectal cancer confers no increased risk of anastomotic leakage. Br J Surg 99:127–132

Hinoi T, Okajima M, Shimomura M, Egi H, Ohdan H, Konishi F, Sugihara K, Watanabe M (2013) Effect of left colonic artery preservation on anastomotic leakage in laparoscopic anterior resection for middle and low rectal cancer. World J Surg 37:2935–2943

Mihara Y, Kochi M, Fujii M, Kanamori N, Funada T, Teshima Y, Jinno D, Takayama T (2014) Resection of colorectal cancer with versus without preservation of inferior mesenteric artery. Am J Clin Oncol 40:381–385

Yamamoto M, Okuda J, Tanaka K, Ishii M, Hamamoto H, Uchiyama K (2014) Oncological impact of laparoscopic lymphadenectomy with preservation of the left colic artery for advanced sigmoid and rectosigmoid colon cancer. Dig Surg 31:452–458

Boström P, Haapamäki MM, Matthiessen P, Ljung R, Rutegard J, Rutegard M (2015) High arterial ligation and risk of anastomotic leakage in anterior resection for rectal cancer in patients with increased cardiovascular risk. Color Dis 17:1018–1027

Charan I, Kapoor A, Singhal MK, Jagawat N, Bhavsar D, Jain V, Kumar V, Kumar HS (2015) High ligation of inferior mesenteric artery in left colonic and rectal cancers: lymph node yield and survival benefit. Indian J Surg 77:S1103–S1108

Guo YC, Wang DG, He L, Zhang Y, Zhao SS, Zhang LY, Sun X, Suo J (2015) Marginal artery stump pressure in left colic artery-preserving rectal cancer surgery: a clinical trial. ANZ J Surg 87:576–581

Tanaka J, Nishikawa T, Tanaka T, Kiyomatsu T, Hata K, Kawai K, Kazama S, Nozawa H, Yamaguchi H, Ishihara S, Sunami E, Kitayama J, Watanabe T (2015) Analysis of anastomotic leakage after rectal surgery: a case-control study. Ann Med Surg (2012) 4:183–186

Wang QG, Zhang CK, Zhang HY, Wang YH, Yuan ZG, Qu C (2015) Effect of ligation level of inferior mesenteric artery on postoperative defecation function in patients with rectal cancer. Chin J Gastrointest Surg 18:1132–1135

Rutegård M, Hassmén N, Haapamäki MM, Matthiessen P, Rutegård J (2016) Anterior resection for rectal cancer and visceral blood flow: an explorative study. Scand J Surg: SJS: Off Organ Finnish Surg Soc Scand Surg Soc 105:78–83

Yasuda K, Kawai K, Ishihara S, Murono K, Otani K, Nishikawa T, Tanaka T, Kiyomatsu T, Hata K, Nozawa H, Yamaguchi H, Aoki S, Mishim H, Maruyama T, Sako A, Watanabe T (2016) Level of arterial ligation in sigmoid colon and rectal cancer surgery. World J Surg Oncology 14:1 Article Number: 99

Zhang LY, Zang L, Ma JJ, Dong F, He ZR, Zheng MH (2016) Preservation of left colic artery in laparoscopic radical operation for rectal cancer. Chin J Gastrointest Surg 19:886–891

Wu YJ, Li M (2017) Left colon artery preservation in laparoscopic anterior rectal resection: a clinical study. Chin J Gastrointest Surg 20:1313–1315

You XL, Wang YJ, Chen ZY, Li WQ, Xu N, Liu GY, Zhao XJ, Huang CJ (2017) Clinical study of preserving left colic artery during laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for the treatment of rectal cancer. Chinese Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 20:1162–1167

Dimitriou N, Felekouras E, Karavokyros I, Pikoulis E, Vergadis C, Nonni A, Griniatsos J (2018) High versus low ligation of inferior mesenteric vessels in rectal cancer surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J BUON: Off J Balkan Union Oncol 23:1350–1361

Lee KH, Kim JS, Kim JY (2018) Feasibility and oncologic safety of low ligation of inferior mesenteric artery with D3 dissection in cT3N0M0 sigmoid colon cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res 94:209–215

Fen WQ, Zong YP, Sun J, Li W, Zhu CC, Miao YM, Zheng MH, Lu AG (2018) High ligation versus low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery and lymph node dissection in laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery. Chin J Gen Surg 33:563–566

Olofsson F, Buchwald P, Elmstahl S, Syk I (2018) High tie or not in resection for cancer in the sigmoid colon? Scand J Surg:1457496918812198

Xu T, Hu JT (2018) Effect of low ligation and high ligation of inferior mesenteric artery on laparoscopic radical resection of rectal cancer. Chin J Operative Procedures of Gen Surg (Electronic Version) 12:144–147

Zhou JM, Tan SY, Huang J, Huang PZ, Peng SY, Lin JX, Li TY, Wang JP, Huang-MJ (2018) Accurate low ligation of inferior mesenteric artery and root lymph node dissection according to different vascular typing in laparoscopic radical resection of rectal cancer. Chin J Gastrointes Surg 21:46–52

Han C, Shan X, Yao L, Yan P, Li M, Hu L, Tian H, Jing W, Du B, Wang L, Yang K, Guo T (2018) Robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy for benign gallbladder diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 32:4377–4392

Murono K, Kawai K, Kazama S, Ishihara S, Yamaguchi H, Sunami E, Kitayama J, Watanabe T (2015) Anatomy of the inferior mesenteric artery evaluated using 3-dimensional CT angiography. Dis Colon Rectum 58:214–219

Lange MM, Buunen M, van de Velde CJ, Lange JF (2008) Level of arterial ligation in rectal cancer surgery: low tie preferred over high tie. A review Dis Colon Rectum 51:1139–1145

Hida J, Okuno K, Yasutomi M, Yoshifuji T, Uchida T, Tokoro T, Shiozaki H (2005) Optimal ligation level of the primary feeding artery and bowel resection margin in colon cancer surgery: the influence of the site of the primary feeding artery. Dis Colon Rectum 48:2232–2237

Hari DM, Leung AM, Lee JH, Sim MS, Vuong B, Chiu CG, Bilchik AJ (2013) AJCC cancer staging manual 7th edition criteria for colon cancer: do the complex modifications improve prognostic assessment? J Am Coll Surg 217:181–190

Grinnell RS, Hiatt RB (1952) Ligation of the interior mesenteric artery at the aorta in resections for carcinoma of the sigmoid and rectum. Surg Gynecol Obstet 94:526–534

Dworkin MJ, Allen-Mersh TG (1996) Effect of inferior mesenteric artery ligation on blood flow in the marginal artery-dependent sigmoid colon. J Am Coll Surg 183:357–360

Yan P, Yao L, Li H, Zhang M, Xun Y, Li M, Cai H, Lu C, Hu L, Guo T, Liu R, Yang K (2018) The methodological quality of robotic surgical meta-analyses needed to be improved: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol

Bertrand MM, Delmond L, Mazars R, Ripoche J, Macri F, Prudhomme M (2014) Is low tie ligation truly reproducible in colorectal cancer surgery? Anatomical study of the inferior mesenteric artery division branches. Surg Radiol Anat: SRA 36:1057–1062

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the institution (Evidence Based Medicine Center of Lanzhou University) for their help and support to the methodology and meta-process.

Funding

This study was supported by the (1) Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 16LZUJBWTD013, Grant No. 18LZUJBWZX006): evidence-based sociology research; (2) Key Laboratory of Evidence Based Medicine and Knowledge Translation Foundation of Gansu Province (Grant No. GSXZYZH2018006); (3) Laboratory of Intelligent Medical Engineering of Gansu Province (Grant No. GSXZYZH2018001); and (4) Application of Minimally Invasive Technology in Acute Abdomen and Abdominal Injury (Grant No.144FKCA073).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TKG, KHY, and MBS carried out the concepts, design, definition of literature search, data acquisition, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. MBS, PJY, and ZYD provided assistance for data acquisition, data analysis, and statistical analysis. LYL, HWT, and WJJ fulfilled literature search, data acquisition, and quality assessment. WTJ, JY, and CWH accomplished data analysis and statistical analysis. MBS and ZYD wrote the manuscript. Finally, TKG, KHY, and XES reviewed and revised the paper. All authors have read and approve the content of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Mou-Bo Si, Pei-Jing Yan, Zhen-Ying Du, Lai-Yuan Li, Hong-Wei Tian, Jia Yang, Cai-Wen Han, Xiu-E Shi, Ke-Hu Yang, and Tian-Kang Guo have declared no conflict of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Ethical approval

This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis therefore Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not needed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Si, MB., Yan, PJ., Du, ZY. et al. Lymph node yield, survival benefit, and safety of high and low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in colorectal cancer surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 34, 947–962 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-019-03291-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-019-03291-5