Abstract

Purpose

When patients present with a perforation of a colon cancer (CC), this situation increases the challenge to treat them properly. The question arises how to deal with these patients adequately, more restrictively or the same way as with elective cases.

Methods

Between January 1995 and December 2009, 52 patients with perforated CC and 1206 nonperforated CC were documented in the Erlangen Registry of Colorectal Carcinomas (ERCRC). All these patients underwent radical resection of the primary including systematic lymph node dissection with CME. The median follow-up period was 68 months.

Results

The median age of the patients in the perforated CC group was significantly higher than in the nonperforated CC group (p = 0.010). Significantly, more patients with perforated CC were classified in ASA categories 3 and 4 (p = 0.014). Hartmann procedures were performed significantly more frequently with perforation than with the nonperforated ones (p < 0.001). If an anastomosis was performed, the leakage rate of primary anastomoses did not differ (p = 1.0). Cancer-related survival was significantly lower with perforated cancer (difference 12.8 percentage points) and by 9.6 percentage points for observed survival, if postoperative mortality was excluded.

Conclusions

Perforated CC patients should be treated basically following the same oncologic demands, which are CME for colonic cancer including multivisceral resections, if needed. This strategy can only be performed if high-quality surgery is available, permanently.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

When a patient presents with a perforation of a colon cancer, this situation indicates several implications, which are a more advanced tumor stage, increased comorbidities and an increased postoperative risk [1–4]. These patients are even older and carry a higher comorbidity than those operated electively, which increases the challenge to treat them properly [5, 6].

Some guidelines or individual surgeons favor a more conservative approach to this problem [7]. However, if high-quality surgery and proper perioperative management on the same level are available permanently, this concept should be questioned.

Therefore, the question arises how to deal with these patients adequately—more restrictively or the same way as with elective cases.

In the last 20 years, almost, the concept in our department was to operate these patients with perforated colon cancer as much as possible the same way as our guidelines provide for elective cases concerning resection of the primary with radical lymph node dissection following consequently the concept of CME [8–10]. During this period, the surgical procedure did not change.

Material and methods

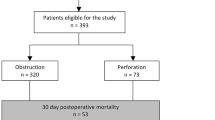

Between January 1995 and December 2009, 1258 patients underwent surgery for colon carcinoma at the Department of Surgery of the University Hospital Erlangen. These patients were prospectively documented using defined proformas of the Erlangen Registry of Colorectal Carcinomas (ERCRC) including general epidemiological data, clinical findings, surgical and neo-/adjuvant treatment, histopathological examinations, postoperative complications, and follow-up data.

Perforated cancer included any sealed or free spontaneous perforation of the colon within or outside the tumor. Perforations following colonoscopy or intraoperative perforations due to surgical failures were not considered as well as those with appendiceal carcinomas or emergencies other than perforation. Carcinomas with familial adenomatous polyposis, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn’s disease were also excluded. Finally, among these 1258 patients, 52 patients with perforated colon carcinoma were identified. On the basis of preoperative risk factors, the patients were assigned to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification. The anatomic disease extend of the tumors were classified by using the UICC TNM classification 2009.

All these patients underwent radical resection of the primary including systematic lymph node dissection as defined by complete mesocolic excision (CME) [10]. If necessary multivisceral resections (e.g., salpingo-oophorectomie, partial gastric resection, resection of the seminal vesicles, infiltrated abdominal wall or parts of the urinary bladder) were performed.

To examine the influence of perforations in colon cancer on the early postoperative outcomes as well as on the long-term survival, these cases were compared with the nonperforated colon carcinomas treated by elective surgery. The postoperative morbidity included general as well as specific postoperative complications (renal, cardiac, pulmonary complications, venous thrombosis or embolism, urinary tract infections, as well as wound infections, dysfunction of the healing process, ileus, or anastomotic leaks). An anastomotic leak was diagnosed by CT scan, enemas with contrast medium or clinical due to pus or fecal discharge from drains, pelvic abscess, or peritonitis.

Postoperative mortality was defined as in hospital mortality, even beyond 30 days.

Patients were followed up until 31 December 2012. The median follow-up period of all patients was 68 months (range 0–217 months), median follow-up of patients still alive was 104 months (range 19–217 months). Disease-free survival and cancer-related survival were calculated for all R0-resected tumors excluding postoperative mortality and tumors with unknown tumor status (Fig. 1).

Follow-up was performed according to the official guidelines for colorectal cancer. Since 2004, we perform anamnesis, physical examinations, CEA, and abdominal sonography in the months 6, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48, and 60 after surgery with additional colonoscopies 6, 12, and 60 months after surgery. If these colonoscopies are inconspicuous, further colonoscopies are all 60 months performed.

Until 2004, we based our follow-up scheme upon the valid guidelines for colorectal cancer at that time. We performed anamnesis, physical examination and abdominal sonography with identical time intervals compared to today. If the whole colon was not investigated by colonoscopy preoperatively the first postoperative colonoscopy was performed 3 months after surgery. Further colonoscopies were performed 24 and 60 months after surgery. If these colonoscopies were inconspicuous, further colonoscopies were performed every 36 months.

Statistical analyses

Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare categorical data and the Mann–Whitney U test for quantitative data. The Kaplan–Meier method was applied for univariable analyses of survival rates. To compare the survival distributions of two samples, the log-rank test was performed. For the analyses of disease-free survival, the first occurrence of locoregional recurrence, distant metastasis, or death due to any cause was defined as an event. For the identification of observed survival, death due to any cause was defined as an event. Death from colorectal cancer, either due to recurrence, or due to postoperative death after reoperation was defined as an event for the estimates of the cancer-related survival. A p value of less than 0.05 was appreciated to be significant. All analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 software.

Statement of human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Patient and tumor characteristics (Tables 1 and 2)

Between January 1995 and December 2009, 1258 patients, matching our inclusion criteria, underwent surgery for colon cancer. Fifty-two (4.1 %) patients presented with a perforated carcinoma. These 52 perforated tumors include 23 (44 %) free perforations and 29 (56 %) sealed perforations. In 16/52 (31 %) cases, these patients underwent surgery as an emergency operated within 6 h and in 25/52 (48 %) cases within 48 h after admission. The perforations of the residual 11 patients (21 %) were detected during scheduled surgery. Six patients underwent emergency surgery due to synchronously perforated colorectal cancers and sigmoid diverticulitis.

The median age of the patients in the perforated colon cancer group was significantly higher than in the nonperforated colon cancer group (p = 0.010). Significantly more patients with perforated colon cancer were classified in ASA categories 3 and 4 (p = 0.014). Most CC with a perforation were localized in the sigmoid colon (28/52, 54 %), followed by the cecum and ascending colon (Table 1).

Patients with a perforation presented with more advanced tumors (T4, N2, or M1) compared to nonperforated ones (Table 2). In the perforated group, 29 % of the patients had prior abdominal surgery and 14 % suffered from diabetes. Patients with perforated colon cancers showed a median BMI of 26 kg/m2 (18–42 kg/m2), a median preoperative albumin of 25.6 g/l (8.0–43.9 g/l) and a median preoperative hemoglobin of 11.5 g/dl (7.3–15.2 g/dl).

Surgery (Table 3)

Perforated colon cancers presented more frequently with peritumorous abscesses (75 %). In the perforation group, Hartmann procedures were performed significantly more frequently (31 %) with perforation than with the nonperforated ones (0.8 %), thus avoiding primary anastomoses mainly with free perforations (Table 3 and 5). Twenty-five of the patients in the perforated group had a diffuse purulent peritonitis, and another 15 % showed fecal peritonitis.

In addition, patients with higher ASA scores received more Hartmann’s resections (p = 0.004). Primary anastomosis was more frequently performed in patients with a lower ASA classification (ASA 1 100 %; ASA 2 93 %) (Tables 3, 4, and 5).

The nonperforated colon cancer group showed higher local R0 resection rates than surgery of perforated colon cancers (2 vs. 1.6 %) and showed a smaller rate of distant metastasis (15.5 vs. 21 %) (Table 3).

Adjuvant therapy

Colon cancers (stage III, R0, exclusion of postoperative mortality) received adjuvant chemotherapy when perforated in 6/13 (46.2 %) cases and when not perforated in 176/277 (63.5 %) cases (p = 0.205).

Postoperative complications (Tables 3 and 4)

Patients with a perforation experienced postoperative complications twice as much than the others (56 vs. 21.6 %; p < 0.001). Postoperative mortality was as well higher (15 vs. 3.1 %).

Anastomoses were omitted throughout all sites within the colon, as well more frequently with perforations. However, if an anastomosis was performed, the leakage rate of primary anastomoses did not differ (in the perforated group, 1/35 = 3 %, and in the nonperforated group, 40/1193 = 3.3 %).

Five-year survival (Table 6)

Cancer-related survival was significantly lower with perforated cancer (difference 12.8 percentage points), and even more by 24.7 percentage points for observed survival, if postoperative mortality was included and by 9.6 percentage points if excluded. The difference increased further for disease-free survival to 29.9 percentage points.

Multivariate analysis

Multivariate analysis revealed the known parameters like stage and R classification to be independent prognostic factors (Table 7). Interestingly, the site also influenced survival favoring sigmoid cancer compared to the residual colon. Finally, however, perforation was an independent prognostic factor.

Discussion

About 1.3 to 5.4 % of all colorectal cancer patients present primarily with a free or sealed perforation of the tumor itself or of the colon upstream due to prolonged complete obstruction and dilatation, finally followed by ischemia [1–3, 11–14]. This is in accordance with the incidence in our patients (4.1 %).

Patients with a gastrointestinal perforation need careful attention and decision making. This is even more important for colonic perforations, as potential stool contamination of the peritoneal cavity carries the highest lethal risk. In coincidence with colon cancer the challenge for proper treatment is even more complex because the affected patients are older as well as more diseased and present frequently a more advanced tumor.

Therefore, the proposals to treat these patients may vary from a relatively conservative approach, for example, just creating a deviating stoma eventually combined with percutaneous CT-guided drainage of an abscess, or eventually segmental resection of the tumor renouncing major lymph node dissection, to a radical procedure inclusive CME even in these situations including resection of the primary with lymph node dissection to the same extend as with elective cases [15]. Finally, the treatment and management of patients presenting with perforated colorectal carcinoma continues to be under debate in the literature [16].

As these patients are not infrequently admitted outside the regular working time, not seldom administrative reasons may also have an impact on decision making [17, 18].

Finally, it is difficult to prove that radical surgery improves the prognosis for perforated colon cancers. We could confirm that patients with perforated colon cancer are even older than those without a perforated tumor [5, 6, 19, 20]. Moreover, our results are in coincidence with the literature that perforated colon carcinoma shows significantly higher T and N categories than nonperforated tumors [11, 19–21].

Surgery

In the meanwhile, there is common sense that colonic perforations need resection of the involved bowel, whether they are free or sealed and independently from the etiology [4]. Although mainly with perforated sigmoid diverticulits conservative treatment [22], percutaneous drainage of an abscess [23] or even just laparoscopic lavage [24] may be an option, too. There is little literature, however, how to proceed with these patients, if the causal condition is colon cancer [4].

The decision making, to perform or restrain from an anastomosis is another issue which is not the objective of this study. The matter is rather, whether radical resection of a primary including CME with central tie of the supplying arteries thus dissecting the most central lymph nodes and even multivisceral resections if oncologically needed to achieve an R0 resection has a negative impact on postoperative morbidity and mortality and any influence on long-term outcome.

Postoperative complications

The rate of postoperative complications after resection of colon cancer is closely related to age, ASA score, and tumor stage (stage IV) and curability (R2) [4]. The same is true with emergency cases compared to elective ones [2]. However, it is open, whether worse outcome with emergencies is, at least in part, just a surrogate parameter for the residual factors of influence. Finally on top, perforations are followed by the highest rate of severe postoperative morbidity and mortality in this context (Table 3) [15].

In our series, postoperative morbidity was in perforated cases with 56 % higher than in the nonperforated group (21.6 %). Perforated tumors also showed higher mortality rates (15 %) than nonperforated ones (3.1 %). Concerning the negative influential factors, the respective patients were significantly older (73 vs. 67 years), had a significantly more advanced ASA score (ASA 3 and 4 47 % vs. 16 %) and pN category (pN2 33 vs. 19 %), which confirms recent data that emergency surgery for perforated colon cancers contributes to a lower R0 resection rate (p = 0.189) [14]. Furthermore, the advanced ASA scores in perforated cancer could explain the high rate of nonsurgical complications (Table 3).

Apart from immanent risks, postoperative septic complications contribute most to postoperative morbidity [1]. With perforated cases, primary anastomoses were more frequently renounced (33 vs. 1.1 %). However, if an anastomosis was performed, in our patient group, the leakage rate was not increased (3 vs. 3.3 %).

In the literature, there is general consent to treat right-sided colorectal cancer perforations with immediate resection and primary anastomosis whereas this strategy is still uncertain for left-sided lesions [25, 26]. In our results, patients with a right or transverse colorectal cancer perforation received a little more frequently resections with primary anastomosis (67 %) than patients with left colon perforation (sigmoid colon 64 %).

In the recent literature, clinical anastomotic leakage rates of 5.4–21.7 % for emergency situations are reported [27]. The incidence of anastomotic dehiscences for resections with primary anastomosis in perforated colon carcinoma in our series was 3 % and similar to the group of nonperforated colorectal carcinoma (3.3 %). Related to the site of the resected bowel, there are relevant differences. In the sigmoid colon, primary anastomosis was performed in 18/28 cases (64 %) without any anastomotic leakage. In the other parts of the colon, primary anastomosis was performed in 16/24 cases (67 %) with only one anastomotic leakage (6 %). Finally, even with a perforation, our results are in line with those reported in the literature for elective cases [28].

Postoperative mortality

Perforated colon carcinomas are generally reported to have an unfavorable prognosis with a lower survival rate and a higher postoperative mortality [1–4, 13, 29–32]. Most important factor for increased postoperative mortality is the higher rate of sepsis [32]. Furthermore, the high postoperative mortality is also associated with poor physical patient’s condition and ASA grading (Table 1) [14]. In our patients with perforated colorectal carcinoma, the postoperative mortality was 15 % which compares favorably with reported rates of 17.0 to 20.2 %, although we performed radical surgery, which means mainly that we stick to CME, which is still infrequently performed in elective cases [1, 2, 4, 33, 34]. Finally, survival and outcome in these cases depend on the general patient’s condition and the severity of the sepsis (Table 3) [29].

Long-term survival

Cancer-related survival without residual tumor (R0) was only slightly, nevertheless significantly lower in perforated cancer (difference 12.8 percentage points); however, the difference increased up to almost 25 percentage points for observed survival, if postoperative mortality was included and to 9.6 percentage points if excluded. This difference is probably mainly related to higher age and comorbidity in the perforated group. The difference increased further for disease-free survival to 29.9 percentage points, as a reason of more advanced tumors. Furthermore, the site also influenced survival favoring sigmoid cancer compared to the residual colon. Finally, multivariate analysis indicated perforation as an independent significant negative factor (Table 7). In this context, observed survival did not show any difference between free and sealed perforation.

The key question is whether perforated colorectal cancer patients can be operated the same way as not perforated ones concerning extend of lymph node dissection and multivisceral resections if necessary with an acceptable postoperative morbidity and mortality and whether long-term oncologic outcome is then improved compared to a more conservative approach.

Actually, considering the increased risk factors in the perforated group namely higher median age, the high rate of ASA 3 an ASA 4 patients (39 and 8 %) and stage IV patients at 25 %, postoperative mortality is in the range of expected outcome reported even for elective surgery (ASA 3/4 20.9/10.7 % [35] and 17.7/37.3 % [36]). However, without regard of these high-risk features, even for perforated colonic diverticulitis increased morbidity (67–75 %) [37] and mortality up to 9.9–18.8 % is reported [38], although these patients are younger with a median age of 65 years [39].

Long-term outcome is significantly reduced following treatment of perforated colon cancer. Firstly, however, free perforations are reported to drop tremendously even down to 15 % disease-free survival compared to 38 % with sealed perforations (adjusted observed survival 44 and 38 %) [4]. Observed survival of all patients in our study is in a similar range, however higher, if curative surgery only was analyzed leading to a cancer-related survival of 76.3 % and disease-free survival of 42.9 % with no difference between free or sealed perforations.

Compared to other studies which analyzed the outcome of perforated colon cancers, our study shows the highest cancer-related survival rate [40–42].

Notably, the cancer-related survival of 76.3 % in this study is in accordance with cancer-related survival rates in elective cases without perforations on other centers 65.9–72.0 % [43, 44].

Finally, our results indicate that perforated colon cancer patients should be treated basically following the same oncologic demands, which are complete mesocolic excision for colonic cancer including multivisceral resections, if needed. This strategy, however, can be translated into practice only, if high-quality surgery is available 24/7.

References

Abdelrazeq AS, Scott N, Thorn C, Verbeke CS, Ambrose NS, Botterill ID, Jayne DG (2008) The impact of spontaneous tumour perforation on outcome following colon cancer surgery. Colorectal Dis 10(8):775–780. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01412.x

Cheynel N, Cortet M, Lepage C, Ortega-Debalon P, Faivre J, Bouvier AM (2009) Incidence, patterns of failure, and prognosis of perforated colorectal cancers in a well-defined population. Dis Colon Rectum 52(3):406–411. doi:10.1007/DCR.0b013e318197e351

Lee IK, Sung NY, Lee YS, Lee SC, Kang WK, Cho HM, Ahn CH, Lee do S, Oh ST, Kim JG, Jeon HM, Chang SK (2007) The survival rate and prognostic factors in 26 perforated colorectal cancer patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 22(5):467–473. doi:10.1007/s00384-006-0184-8

Zielinski MD, Merchea A, Heller SF, You YN (2011) Emergency management of perforated colon cancers: how aggressive should we be? J Gastrointest Surg 15(12):2232–2238. doi:10.1007/s11605-011-1674-8

Alvarez JA, Baldonedo RF, Bear IG, Truan N, Pire G, Alvarez P (2005) Presentation, treatment, and multivariate analysis of risk factors for obstructive and perforative colorectal carcinoma. Am J Surg 190(3):376–382. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.01.045

Coco C, Verbo A, Manno A, Mattana C, Covino M, Pedretti G, Petito L, Rizzo G, Picciocchi A (2005) Impact of emergency surgery in the outcome of rectal and left colon carcinoma. World J Surg 29(11):1458–1464. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-7826-9

Charbonnet P, Gervaz P, Andres A, Bucher P, Konrad B, Morel P (2008) Results of emergency Hartmann’s operation for obstructive or perforated left-sided colorectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol 6:90. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-6-90

Pox CP, Schmiegel W (2013) German S3-guideline colorectal carcinoma. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 138(49):2545. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1353953

West NP, Hohenberger W, Weber K, Perrakis A, Finan PJ, Quirke P (2010) Complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation produces an oncologically superior specimen compared with standard surgery for carcinoma of the colon. J Clin Oncol 28(2):272–278. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.24.1448

Hohenberger W, Weber K, Matzel K, Papadopoulos T, Merkel S (2009) Standardized surgery for colonic cancer: complete mesocolic excision and central ligation--technical notes and outcome. Colorectal Dis 11(4):354–364. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01735.x, discussion 364–355

Ghazi S, Berg E, Lindblom A, Lindforss U (2013) Clinicopathological analysis of colorectal cancer: a comparison between emergency and elective surgical cases. World J Surg Oncol 11:133. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-11-133

Ho YH, Siu SK, Buttner P, Stevenson A, Lumley J, Stitz R (2010) The effect of obstruction and perforation on colorectal cancer disease-free survival. World J Surg 34(5):1091–1101. doi:10.1007/s00268-010-0443-2

Wong SK, Jalaludin BB, Morgan MJ, Berthelsen AS, Morgan A, Gatenby AH, Fulham SB (2008) Tumor pathology and long-term survival in emergency colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 51(2):223–230. doi:10.1007/s10350-007-9094-2

Schwenter F, Morel P, Gervaz P (2010) Management of obstructive and perforated colorectal cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 10(10):1613–1619. doi:10.1586/era.10.147

Merkel S, Meyer C, Papadopoulos T, Meyer T, Hohenberger W (2007) Urgent surgery in colon carcinoma. Zentralbl Chir 132(1):16–25. doi:10.1055/s-2006-958708

Anderson JH, Hole D, McArdle CS (1992) Elective versus emergency surgery for patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 79(7):706–709

Zorcolo L, Covotta L, Carlomagno N, Bartolo DC (2003) Toward lowering morbidity, mortality, and stoma formation in emergency colorectal surgery: the role of specialization. Dis Colon Rectum 46(11):1461–1467. doi:10.1097/01.DCR.0000095228.91284.AE, discussion 1467–1468

Hermanek P Jr, Wiebelt H, Riedl S, Staimmer D, Hermanek P (1994) Long-term results of surgical therapy of colon cancer. Results of the Colorectal Cancer Study Group. Chirurg 65(4):287–297

Gunnarsson H, Jennische K, Forssell S, Granstrom J, Jestin P, Ekholm A, Olsson LI (2014) Heterogeneity of colon cancer patients reported as emergencies. World J Surg 38(7):1819–1826. doi:10.1007/s00268-014-2449-7

van der Sluis FJ, Espin E, Vallribera F, de Bock GH, Hoekstra HJ, van Leeuwen BL, Engel AF (2014) Predicting postoperative mortality after colorectal surgery: a novel clinical model. Colorectal Dis 16(8):631–639. doi:10.1111/codi.12580

Burton S, Norman AR, Brown G, Abulafi AM, Swift RI (2006) Predictive poor prognostic factors in colonic carcinoma. Surg Oncol 15(2):71–78. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2006.08.003

Ambrosetti P, Gervaz P, Fossung-Wiblishauser A (2012) Sigmoid diverticulitis in 2011: many questions; few answers. Colorectal Dis 14(8):e439–e446. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03026.x

McDermott FD, Collins D, Heeney A, Winter DC (2014) Minimally invasive and surgical management strategies tailored to the severity of acute diverticulitis. Br J Surg 101(1):e90–e99. doi:10.1002/bjs.9359

Afshar S, Kurer MA (2012) Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage for perforated sigmoid diverticulitis. Colorectal Dis 14(2):135–142. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02606.x

Runkel NS, Hinz U, Lehnert T, Buhr HJ, Herfarth C (1998) Improved outcome after emergency surgery for cancer of the large intestine. Br J Surg 85(9):1260–1265

Poon RT, Law WL, Chu KW, Wong J (1998) Emergency resection and primary anastomosis for left-sided obstructing colorectal carcinoma in the elderly. Br J Surg 85(11):1539–1542. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00903.x

Schrock TR, Deveney CW, Dunphy JE (1973) Factor contributing to leakage of colonic anastomoses. Ann Surg 177(5):513–518

Krarup PM, Jorgensen LN, Harling H (2014) Management of anastomotic leakage in a nationwide cohort of colonic cancer patients. J Am Coll Surg 218(5):940–949. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.01.051

Runkel NS, Schlag P, Schwarz V, Herfarth C (1991) Outcome after emergency surgery for cancer of the large intestine. Br J Surg 78(2):183–188

Sperling D, Spratt JS Jr, Carnes VM (1963) Adenocarcinoma of the Large Intestine with Perforation. Mo Med 60:1104–1107

Miller LD, Boruchow IB, Fitts WT Jr (1966) An analysis of 284 patients with perforative carcinoma of the colon. Surg Gynecol Obstet 123(6):1212–1218

Peloquin AB (1975) Factors influencing survival with complete obstruction and free perforation of colorectal cancers. Dis Colon Rectum 18(1):11–21

Chen HS, Sheen-Chen SM (2000) Obstruction and perforation in colorectal adenocarcinoma: an analysis of prognosis and current trends. Surgery 127(4):370–376

Koperna T, Kisser M, Schulz F (1997) Emergency surgery for colon cancer in the aged. Arch Surg 132(9):1032–1037

Osler M, Iversen LH, Borglykke A, Martensson S, Daugbjerg S, Harling H, Jorgensen T, Frederiksen B (2011) Hospital variation in 30-day mortality after colorectal cancer surgery in denmark: the contribution of hospital volume and patient characteristics. Ann Surg 253(4):733–738. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e318207556f

Iversen LH (2012) Aspects of survival from colorectal cancer in Denmark. Dan Med J 59(4):B4428

Dixon E, Buie WD, Heise CP (2014) What is the preferred surgery for perforated left-sided diverticulitis? J Am Coll Surg 218(3):495–497. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.011

Meyer F, Grundmann RT (2011) Hartmann’s procedure for perforated diverticulitis and malignant left-sided colorectal obstruction and perforation. Zentralbl Chir 136(1):25–33. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1262753

Thornell A, Angenete E, Haglind E (2011) Perforated diverticulitis operated at Sahlgrenska University Hospital 2003–2008. Dan Med Bull 58(1):A4173

Anwar MA, D’Souza F, Coulter R, Memon B, Khan IM, Memon MA (2006) Outcome of acutely perforated colorectal cancers: experience of a single district general hospital. Surg Oncol 15(2):91–96. doi:10.1016/j.suronc.2006.09.001

Biondo S, Kreisler E, Millan M, Fraccalvieri D, Golda T, Marti Rague J, Salazar R (2008) Differences in patient postoperative and long-term outcomes between obstructive and perforated colonic cancer. Am J Surg 195(4):427–432. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.02.027

Amri R, Bordeianou LG, Sylla P, Berger DL (2015) Colon cancer surgery following emergency presentation: effects on admission and stage-adjusted outcomes. Am J Surg 209(2):246–253. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.07.014

McArdle CS, McMillan DC, Hole DJ (2003) Male gender adversely affects survival following surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 90(6):711–715. doi:10.1002/bjs.4098

Widdison AL, Barnett SW, Betambeau N (2011) The impact of age on outcome after surgery for colorectal adenocarcinoma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 93(6):445–450. doi:10.1308/003588411X587154

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Daniels, M., Merkel, S., Agaimy, A. et al. Treatment of perforated colon carcinomas—outcomes of radical surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 30, 1505–1513 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-015-2336-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-015-2336-1