Abstract

Background

Controlled delivery of radio frequent energy (Secca) has been suggested as treatment for faecal incontinence (FI).

Objective

The objective of the study is to evaluate clinical response and sustainability of Secca for FI.

Design

This is a prospective cohort study.

Patients

This study involved patients who had failed full conservative management for FI.

Interventions

This study was performed between 2005 and 2010.

Main outcome measures

FI was scored using the Vaizey score (VS). A clinically significant response to Secca was defined as ≥50 % reduction in incontinence score. Impact of FI on quality of life (QOL) was measured using the FIQL. Data was obtained at baseline, at 6 months and at 1 and 3 years. Anal endosonography and anal manometry were performed at 3 months and compared to baseline.

Results

Thirty-one patients received Secca. During follow-up, 5/31 (16 %), 3/31 (10 %) and 2/31 (6 %) of patients maintained a clinically significant response after the Secca procedure. Mean VS of all patients was 18 (SD 3), 14 (SD 4), 14 (SD 4) and 15 (SD 4), at baseline, 6 months and 1 and 3 years. No increases in anorectal pressures or improvements in rectal compliance were found. Coping improved between baseline and t = 6 months. No predictive factors for success were found.

Limitations

This is a non-randomised study design.

Conclusion

This prospective non-randomised trial showed disappointing outcomes of the Secca procedure for the treatment of FI. The far minority of patients reported a clinically significant response of seemingly temporary nature. Secca might be valuable in combination with other interventions for FI, but this should be tested in strictly controlled randomised trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Faecal incontinence (FI) is defined as the loss of anal sphincter control leading to unwanted release of stool or gas. It is often experienced as a debilitating disease with diminished self-esteem, social isolation and stigmatisation. Furthermore, anxiety regarding anticipated accidents can seriously impair experienced quality of life. The prevalence of FI is estimated at 6–7 % in the general population and rises with age up to 20 % in the elderly [1, 2].

Although pathophysiologic mechanisms of FI development often overlap, they can be categorised into four groups, namely, anal sphincter dysfunction, pudendal nerve neuropathy, poor rectal sensation and impaired rectal compliance. Management of FI starts with supplementation of dietary fibre, physiotherapy and biofeedback techniques [3]. If unsuccessful, surgical procedures such as anal sphincteroplasty, sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) or artificial bowel sphincteroplasty implantation may be appropriate. When medical and surgical treatment options fail, patients appear to have no other choice than to live with their incontinence or undergo a diverting stoma. Therefore, new treatment options such as the less invasive Secca procedure are interesting. It provides delivery of temperature-controlled radiofrequency energy into the muscles of the anorectum [4]. The alleged beneficial effect may be due to the tightening of the anorectum after administered fibrosis which results in a reduction of the rectal sensation volumes [5]. As a consequence, the patient senses distension earlier and therefore has additional time to reach the toilet. The first studies evaluating Secca show substantial reductions in incontinence scores, [6, 7]; however, true clinical significance of these results is questionable, and data on long-term outcome of Secca is scarce. Therefore, this study set out to investigate short-term clinical response, objectify anorectal function alteration and provide long-term outcomes of the Secca procedure for FI.

Methods

The present study consists of a cohort of patients previously reported (n = 11) [8] and an additional set of patients (n = 20). All Secca treatments were performed between 2005 and 2010. All patients had failed previous conservative treatment (including physiotherapy for 3 months). We included patients with a Vaizey score (VS) of at least 12 as we set out to study a group with severe FI [9]. Regarding complaints the primary outcome is the Vaizey Score which was scored before the procedure and at 6 months, and at 1 and 3 years after Secca. Patients with a reduction of ≥50 % in VS at t = 6 months compared to baseline were scored as having a clinically significant response to Secca. The 20 patients included in addition to the pilot study also completed the faecal incontinence quality of life questionnaire (FIQL) which we used to quantify the impact of FI on experienced quality of life. Visual analog pain scores were measured at the end of the procedure and at 1 week and 3 weeks post-therapy (0 = no discomfort; 10 = extreme pain). All patients underwent anorectal manometry and anal endosonography before and at 3 months after the Secca. Recipients who had no improvement 1 year after Secca were offered a referral for sacral nerve stimulation (SNS). The Medical Ethical Commission of the VU University Medical Center granted permission, and all patients gave informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

The Secca procedure

The Secca procedure was performed as an outpatient procedure in the endoscopy unit. Eight hours before the procedure, patients were instructed to take antibiotics, namely, a combination of metronidazole 500 mg and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 500/125 mg. One hour before the procedure, patients were given a rectal enema. The patients were sedated with 0.05 mg fentanyl and 7.5 mg midazolam intravenously. Local perianal anaesthesia with 10 ml of lidocaine 0.5 % with epinephrine 1:200.000 was administered in four quadrants. Patients were examined supine in the lithotomy position. The Secca device was introduced into the anal canal allowing good visual control of electrode placement. Once the applicator is satisfactorily in place, radiofrequency energy was delivered via four needles circumferentially in four quadrants at five different insertion levels of each 0.5 cm starting at the dentate line. The procedure was temperature-controlled with a target site temperature of 85 °C. This resulted in a total of 20 radiofrequency deliveries with 60–80 thermal lesions. Immediately after the procedure and 8 h later, the antibiotic combination was repeated.

Anorectal manometry and anal endosonography

A four-microtip transducer, water-perfused catheter (Mui Scientific Type SR4B-5-0-0-0, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) was used. The maximum basal pressure (MBP), maximum squeeze pressure (MSP), sphincter length and rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR) were assessed. The MBP was measured as the mean of the highest pressures at rest, and the MSP was measured as the mean increase of pressure above the MBP during squeezing. Rectal capacity was determined with a latex balloon in the rectum, which was manually inflated with air. The volume of air required to initiate the first sensation of rectal distension, the urge to defecate and the onset of intolerable distension, which is similar to rectal capacity, were measured.

Anal endosonography was performed using a three-dimensional diagnostic ultrasound system (Hawk type 2050, B-K Medical, Naerum, Denmark). The aspect of the puborectalis muscle, external anal sphincter, internal anal sphincter and submucosa was described.

Statistical analysis

Differences were analysed statistically by our registered statistics using the paired t test; when a non-Gaussian distribution was present, the Wilcoxin rank test was used. The independent t test was used to compare patients with and without a response. The Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

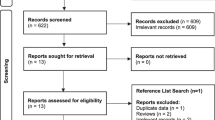

During the study period, 201 Secca candidates were evaluated for FI. Patients were excluded for a variety of reasons (Table 1). The assessment identified 55 patients with FI with a VS ≥12. Additional medical therapy and optimization of fibre therapy and defecation habits combined with pelvic floor physiotherapy further improved symptoms in 22 patients (29 %). Two patients refused the Secca procedure, which left a study population of 31 patients. The main causes of FI were either idiopathic or included obstetric injury, ageing or trauma from previous anorectal surgeries.

Tolerability and safety

The procedure was well tolerated and there were no serious adverse events. Mean pain visual analog scale score was 3.9 (range 0–10), 3.3 (range 0–9) and 1.2 (range 0–6) during the procedure, after 1 week and after 3 weeks, respectively. Other side effects were minor bleeding or hematoma (n = 8), diarrhoea associated with antibiotic intake (n = 7), urinary tract infection (n = 1) and temporary discharge of mucus with stool (n = 1). Due to diarrhoea and undergoing the procedure, most of the patients felt worsening of FI during the first week. There were no long-term complications.

Clinical response at 6 months

Mean VS at baseline was 18 (SD 3) [95 % BI; 17–19] and 14 (SD 5) at 6 months, p < 0.001. Five patients (16 %) showed a ≥50 % decrease in Vaizey score as mean VS decreased from 17 (SD 3) to 8 (SD 1), p = 0.040. In the 26 patients (84 %) without a 50 % reduction, VS lowered from 18 (SD 3) to 15 (SD 4), p < 0.001. If clinical response was defined as a ≤20 % decrease in Vaizey score, response rate was 38 %, in which mean VS decreased from 17 (3) to 11 (3) p < 0.001. Characteristics of patients with and without a ≥50 % decrease in Vaizey score are shown in Table 2. No statistically significant differences between groups could be shown. On the FIQL scales, lifestyle, depression and embarrassment scores were not improved, with the exception of the coping score (1.5 (SD 0.5) at baseline to 1.9 (SD 0.7) at 6 months), p = 0.008. There was no larger increase of FIQL in those with a response. Compared to baseline, no significant differences in anorectal manometry measurements became apparent, see Table 3. No differences in anorectal function evaluation between patients with and without a clinical response were found.

Sustainability of clinical response

After 1 year, three patients (10 %) still experienced a clinical response as in these three VS decreased from 17 (SD 3) to 8 (SD 1). Three years after Secca, two patients had maintained a ≥50 % decrease in Vaizey score, mean VS had decreased from 17 (SD 3) to 9 (SD 3). If clinical response was defined as a ≤20 % decrease in Vaizey score, response rate at 3 years was 19 % in which mean VS decreased from 18 (2) to 11 (2), p < 0.001. None of the 31 patients underwent any additional surgical intervention after Secca. Mean Vaizey scores of all 31 patients categorised into patients with and without a response at 6 months are shown in Fig. 1. Comparison of the Vaizey scores and FIQL at 6 months and at 1 and 3 years showed no significant improvement over time; nonetheless, the increase of FIQL remained stable up to 3 years after procedure, see Fig. 2.

Discussion

This is the second largest prospective study up to date evaluating safety, short-term clinical response and long-term outcomes of controlled delivery of radio frequent energy to the anorectum in patients with FI. We confirmed that the Secca procedure is a safe and well-tolerated procedure without any serious short- or long-term complications. A clinically significant response to Secca procedure was seen in the far minority of patients with a shift towards loss of response during follow-up, giving the impression that clinical response, if realised, was mainly temporary.

This study had several limitations as it lacked a randomised sham-controlled design. In addition, it was underpowered to detect any association between patient-related characteristics and outcome. In spite of these limitations, the outcomes of this study provide a substantive contribution regarding both short- and long-term efficacy of this available procedure. The Secca device received Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) clearance in March 2002. According to the guidelines for the treatment of FI from the Practice Task Force of The American Sciety of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, the Secca procedure is classified as a potentially useful intervention based on level 3 evidence, due to the limited data regarding this treatment modality. In Europe, more than 500 Secca have been done since the re-launch in 2006. Secca is performed in the UK, Germany, Italy, Spain and Turkey. Therefore, the findings of this study are a valuable addition to the scarce literature currently available. Furthermore, this is the largest study evaluating long-term outcomes as most follow-up periods reported in other studies vary from 6 to 12 months [8, 10–13].

The clinical response rate of this study is not as good as the pilot study by Takahashi et al. [5], who reported an 80 % response rate at 1 year and no decrement in effect in any parameter between 12 and 24 months [14]. Furthermore, in 2008, they reported a clinical response 5 years after Secca in 84 % of 19 patients treated with Secca. The overtime decline we found contradicts the sustained response found by Takahashi et al. However, not all patients included by Takahashi et al. had undergone complete conservative management which is still the first-line treatment of FI, and information regarding additional conservative or surgical interventions during follow-up is lacking. Interestingly, during our study, 22 (29 %) of potential Secca candidates were excluded from participation; hence, optimization of fibre therapy in combination with pelvic floor education and physiotherapy further improved complaints.

Lefebure et al. studied the efficacy of the Secca procedure in 15 patients [11]. All included patients had attempted prior conservative and/or surgical theatment without being satisfied with the results. A clinical response was seen in 13 % of patients at 1 year which was similar to results of Ruiz et al. [13].

Efron et al. conducted a large multicentre study including 50 patients [10]. Based on a response defined as at least 10 % improvement in symptoms, 60 % of patients were considered responders. See Table 4 for the studies investigating the efficacy of the Secca procedure and their definitions used to determine clinical response.

So, is there a place for Secca in the stepwise treatment of FI? First-line conservative treatment includes optimum fibre intake, pharmacological management and pelvic floor biofeedback which have a clinical response rate of between 50 and 90 % [15, 16]. Nevertheless, patients need follow-up evaluation as initial response to conservative treatment tends to regress as a function of time [17].

Anal sphincteroplasty is usually indicated for persistent FI after obstetric anal sphincter injuries or after iatrogenic damage sustained during anorectal surgery. It is usually reserved for those patients who have failed conservative treatment. However, not all patients are suitable for anal sphincteroplasty as pre-operatively assessed sphincter defect size influences expected surgical outcome. A prospective study scoring functional results of anal sphincteroplasty in 65 patients using decreases in Wexner score found excellent results in 55.5 % and poor results in 9.2 % of patients 3 months post-sphincteroplasty [18]. At 80 months, percentages had changed to 26.8 and 39.3 %, respectively. A systematic review by Glasgow et al. [19] in 2012 evaluating functional outcome beyond 5 years in 900 patients undergoing anal sphincteroplasty for faecal incontinence demonstrated a similar overtime decline. However, most patients remained satisfied with their surgical outcome post-sphincteroplsaty.

When conservative treatments fail and patients are not eligible for, or results are disappointing after, anal sphincteroplasty, remaining treatment options are limited. Minimally invasive procedures such as the injection of bulking agents may have short-term benefits in patients with an internal sphincter defect and moderate FI; however, results seem inadequate [20, 21].

Large surgical procedures include implantation of an artificial bowel sphincter, graciloplasty or dynamic graciloplasty. Even though they can be considered for some patients with end stage FI, these procedures are associated with high morbidity rates, long-term failure and significant complications during removal [22, 23].

Other options are SNS and Secca. SNS has been accepted as a treatment for severe FI with improving short- and long-term results [7]. In the first stage of the procedure, several of the s2–s4 foramina are cannulated and tested for optimal response. Eligibility for this trial stimulation is around 80 % and not all patients have a positive response. During the second stage, a tined lead is introduced and connected to a permanent stimulator surgically placed in a deep subcutaneous position in the gluteal region. However, in 37 % device revision, replacement or explant was required [24, 25]. A recent 5-year follow-up study of 120 patients found therapeutic success (defined as a >50 % improvement of FI episodes per week) in 89 % and complete continence in 36 % of patients undergoing implantation [24, 26].

A recent review assessing the results of Secca [27] in 220 patients concluded that after appropriate patient selection, a clinically significant improvement was demonstrated. However, no concrete predictive factors for treatment success were found, and a demonstrated clinically significant improvement was noted as a statistically significant reduction in incontinence score. Even though we demonstrated an overall improvement in measured Vaizey score after Secca, a clinically significant response defined as ≥50 % reduction in incontinence score (the cut-off used in most studies investigating treatment efficacy in faecal incontinence) was seen in only 16 % of patients. When considering a reduction of ≤20 % in incontinence score, a clinically significant response was seen in 38 % at 6 months which decreased to 19 % at 3 years.

We were unable to explain the improvements in incontinence scores as we did not record any changes in anorectal manometry, rectal compliance or anal endosonography. And how come all patients seem to lose experienced improvement over time? It is unlikely that the fibrosis becomes less, and even though the pathological process causing faecal incontinence may worsen over time, results may just purely relate to a placebo effect.

However, the minimally invasive aspect, the low cost and the positive effect on experienced quality of life may potentially, when combined with other interventions, represent an option for patients with moderate FI. As the majority of patients included in this study remained moderately or severely incontinent after Secca, it could possibly be used as a prognostic negative subgroup. We believe further research regarding patient characteristics associated with treatment success is needed; however, this should strictly be performed in sham-controlled randomised trials.

Conclusion

This large prospective non-randomised study found disappointing outcomes of the Secca procedure for the treatment of FI. The far minority of patients reported a clinically significant response of seemingly temporary nature. Until randomised controlled trials are performed, we do not believe there is a place for Secca as a single treatment modality for FI.

References

Buckley BS, Lapitan MC (2009) Prevalence of urinary and faecal incontinence and nocturnal enuresis and attitudes to treatment and help-seeking amongst a community-based representative sample of adults in the United Kingdom. Int J Clin Pract 63(4):568–573

Leung FW, Rao SS (2009) Fecal incontinence in the elderly. Gastroenterol Clin N Am 38(3):503–511

Bharucha AE, Wald AM (2010) Anorectal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol 105(4):786–794

Parisien CJ, Corman ML (2005) The Secca procedure for the treatment of fecal incontinence: definitive therapy or short-term solution. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 18(1):42–45

Takahashi T, Garcia-Osogobio S, Valdovinos MA, Mass W, Jimenez R, Jauregui LA, Bobadilla J, Belmonte C, Edelstein PS, Utley DS (2002) Radio-frequency energy delivery to the anal canal for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 45(7):915–922

Abbas MA, Tam MS, Chun LJ (2012) Radiofrequency treatment for fecal incontinence: is it effective long-term? Dis Colon Rectum 55(5):605–610

Takahashi-Monroy T, Morales M, Garcia-Osogobio S, Valdovinos MA, Belmonte C, Barreto C, Zarate X, Bada O, Velasco L (2008) SECCA procedure for the treatment of fecal incontinence: results of five-year follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum 51(3):355–359

Felt-Bersma RJ, Szojda MM, Mulder CJ (2007) Temperature-controlled radiofrequency energy (SECCA) to the anal canal for the treatment of faecal incontinence offers moderate improvement. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 19(7):575–580

Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, Kamm MA (1999) Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut 44(1):77–80

Efron JE, Corman ML, Fleshman J, Barnett J, Nagle D, Birnbaum E, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Sligh S, Rabine J, Wexner SD (2003) Safety and effectiveness of temperature-controlled radio-frequency energy delivery to the anal canal (Secca procedure) for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 46(12):1606–1616

Lefebure B, Tuech JJ, Bridoux V, Gallas S, Leroi AM, Denis P, Michot F (2008) Temperature-controlled radio frequency energy delivery (Secca procedure) for the treatment of fecal incontinence: results of a prospective study. Int J Color Dis 23(10):993–997

Kim DW, Yoon HM, Park JS, Kim YH, Kang SB (2009) Radiofrequency energy delivery to the anal canal: is it a promising new approach to the treatment of fecal incontinence? Am J Surg 197(1):14–18

Ruiz D, Pinto RA, Hull TL, Efron JE, Wexner SD (2010) Does the radiofrequency procedure for fecal incontinence improve quality of life and incontinence at 1-year follow-up? Dis Colon Rectum 53(7):1041–1046

Takahashi T, Garcia-Osogobio S, Valdovinos MA, Belmonte C, Barreto C, Velasco L (2003) Extended two-year results of radio-frequency energy delivery for the treatment of fecal incontinence (the Secca procedure). Dis Colon Rectum 46(6):711–715

Bliss DZ, Jung HJ, Savik K, Lowry A, LeMoine M, Jensen L, Werner C, Schaffer K (2001) Supplementation with dietary fiber improves fecal incontinence. Nurs Res 50(4):203–213

Lee BH, Kim N, Kang SB, Kim SY, Lee KH, Im BY, Jee JH, Oh JC, Park YS, Lee DH (2010) The long-term clinical efficacy of biofeedback therapy for patients with constipation or fecal incontinence. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 16(2):177–185

Ferrara A, De JS, Gallagher JT, Williamson PR, Larach SW, Pappas D, Mills J, Sepulveda JA (2001) Time-related decay of the benefits of biofeedback therapy. Tech Coloproctol 5(3):131–135

Barisic GI, Krivokapic ZV, Markovic VA, Popovic MA (2006) Outcome of overlapping anal sphincter repair after 3 months and after a mean of 80 months. Int J Color Dis 21(1):52–56

Glasgow SC, Lowry AC (2012) Long-term outcomes of anal sphincter repair for fecal incontinence: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum 55(4):482–490

Tjandra JJ, Lim JF, Hiscock R, Rajendra P (2004) Injectable silicone biomaterial for fecal incontinence caused by internal anal sphincter dysfunction is effective. Dis Colon Rectum 47(12):2138–2146

Altomare DF, La TF, Rinaldi M, Binda GA, Pescatori M (2008) Carbon-coated microbeads anal injection in outpatient treatment of minor fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 51(4):432–435

Devesa JM, Rey A, Hervas PL, Halawa KS, Larranaga I, Svidler L, Abraira V, Muriel A (2002) Artificial anal sphincter: complications and functional results of a large personal series. Dis Colon Rectum 45(9):1154–1163

Wong WD, Congliosi SM, Spencer MP, Corman ML, Tan P, Opelka FG, Burnstein M, Nogueras JJ, Bailey HR, Devesa JM, Fry RD, Cagir B, Birnbaum E, Fleshman JW, Lawrence MA, Buie WD, Heine J, Edelstein PS, Gregorcyk S, Lehur PA, Michot F, Phang PT, Schoetz DJ, Potenti F, Tsai JY (2002) The safety and efficacy of the artificial bowel sphincter for fecal incontinence: results from a multicenter cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum 45(9):1139–1153

Hull T, Giese C, Wexner SD, Mellgren A, Devroede G, Madoff RD, Stromberg K, Coller JA (2013) Long-term durability of sacral nerve stimulation therapy for chronic fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 56(2):234–245

Damon H, Barth X, Roman S, Mion F (2013) Sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence improves symptoms, quality of life and patients’ satisfaction: results of a monocentric series of 119 patients. Int J Color Dis 28(2):227–233

Maeda Y1, Lundby L, Buntzen S, Laurberg S (2013) Outcome of Sacral Nerve Stimulation for Fecal Incontinence at 5 Years. Ann Surg, in press

Frascio M, Mandolfino F, Imperatore M, Stabilini C, Fornaro R, Gianetta E, Wexner SD (2014) The SECCA procedure for faecal incontinence: a review. Colorectal Dis. 16(3):167–72. doi:10.1111/codi.12403

Conflict of interest

None declared. The Secca devices are manufactured by Mederi Therapeutics. However, Mederi Therapeutics did not play any role in the design and conduct of the study. Furthermore, Mederi Therapeutics neither has any input into the review of the results and writing this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

T. J. Lam and A. P. Visscher contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lam, T.J., Visscher, A.P., Meurs-Szojda, M.M. et al. Clinical response and sustainability of treatment with temperature-controlled radiofrequency energy (Secca) in patients with faecal incontinence: 3 years follow-up. Int J Colorectal Dis 29, 755–761 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-014-1882-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-014-1882-2