Abstract

Purpose

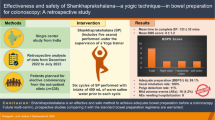

The detailed efficacy of intraluminal l-menthol for preventing colonic spasm is not known. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of l-menthol in preventing colonic spasm during colonoscopy.

Methods

We analyzed 65 patients (mean age: 71.7 years; 49 men and 16 women) who were administered 0.8 % l-menthol (MINCLEA, Nihon Seiyaku, Tokyo, Japan) intraluminally for severe colonic spasm during colonoscopic examination at Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine between February 2012 and May 2013. The efficacy of l-menthol was defined as the absence of colonic spasm during a period of 30 s, and its effect was evaluated at 30 s, 1 min, and 5 min after administration. Additionally, various characteristics of these patients were analyzed. Twenty-seven patients with severe colonic spasm were administered intraluminal water and assessed as controls.

Results

l-Menthol was effective in preventing colonic spasms in 60.0 %, 70.8 %, and 46.5 % of patients at 30 s, 1 min, and 5 min, respectively. In contrast, water was effective in 22.2 %, 29.6 %, and 48.1 % of patients at 30 s, 1 min, and 5 min, respectively. There was a significant difference about the efficacy at 30 s and 1 min between l-menthol and water (P = 0.0009, P = 0.0006).

Conclusions

l-Menthol (0.8 %) was effective in preventing colonic spasm during colonoscopic examination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colonoscopic examination is considered an effective approach for the detection, diagnosis, and treatment of colorectal neoplastic lesions. Chromoendoscopy, using Kudo and Tsuruta’s pit pattern classification, is a powerful tool for the differential diagnosis of colorectal polyps [1–3]. Equipment-based image-enhanced endoscopy procedures, including narrow-band imaging (Olympus Medical Co., Tokyo, Japan), flexible spectral imaging color enhancement (Fujifilm Co., Tokyo, Japan), and blue laser imaging (Fujifilm Co.), have many advantages for the diagnosis of colorectal polyps [4–7]. Additionally, the improvement of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection enabled curative resection for early colorectal cancers [8–11]. However, colonic spasm during colonoscopic examination impedes accurate diagnosis and therapy. In Japan, usually a cholinergic blocker (Buscopan) is administered intravenously or intramusclularly to prevent colonic spasm. However, the use of this drug is contraindicated in patients with heart disease, prostatic hypertrophy, and narrow angle glaucoma. Elderly patients have a higher possibility of having these diseases; hence, safer drugs to prevent colonic spasm are needed. Peppermint oil has been reported to have a direct relaxing effect on smooth muscle in the colon [12]. The mechanism of smooth muscle relaxation has been investigated in animal models and the effect is the result of dihydropyridine calcium antagonists that directly reduce calcium influx [13, 14]. Therefore, peppermint oil is also prescribed in patients with irritable bowel syndrome [15]. The major constituents of peppermint oil are l-menthol (30–50 %) and l-menthone (14–32 %). l-Menthol is considered responsible for the spasmolytic effect of peppermint oil [16]. Recently, Japanese national health insurance approved the use of 0.8 % l-menthol solution (MINCLEA; Nihon Seiyaku, Tokyo, Japan) as an antispasmodic agent during diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Many clinical studies have shown the beneficial effect of inhibiting gastric peristalsis during diagnostic and therapeutic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy [17, 18]. For preventing colonic spasm, intraluminal administration of peppermint oil including l-menthol was reported to be effective during colonoscopic examination [19, 20]. However, the detailed efficacy of l-menthol for preventing colonic spasm has remained unclear. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of l-menthol in preventing colonic spasm during colonoscopic examination.

Methods

This was a retrospective single-center study conducted between February 2012 and May 2013 at the Department of Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine. We analyzed 65 patients with severe colonic spasm during colonoscopy who were endoscopically administered with intraluminal 0.8 % l-menthol solution (MINCLEA). The drug of l-menthol (MINCLEA) used in this study was prepared by our department as a clinical research. The solution of the drug was sprinkled through the endoscopic channel without a tube (Fig. 1a). Since l-menthol has a tendency to form bubbles, we added a small amount of dimethicone to the solution to prevent this (Fig. 1b, c). Patients undergoing diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopic examination, including chromoendoscopy and EMR, were enrolled. Patients’ bowels were prepared for colonoscopic examination by having a light meal and sodium picosulfate on the day before the examination and 2 l of polyethylene glycol solution on the morning before the examination. Severe colonic spasm was defined as a continuous spasm during colonoscopy that lasted for at least 20 s. l-Menthol was considered effective if no colonic spasm occurred during a period of 30 s, and its effect was evaluated 30 s, 1 min, and 5 min after intraluminal administration at the same locus. The evaluation at 5 min was performed at a locus different from the point of administration in some cases. We analyzed the antispasmodic effect of l-menthol and the relationship between the effect of l-menthol and the locus of its administration. Additionally, various other characteristics of the patients including their age, sex, and presence of colonic diverticulum and irritable bowel syndrome were analyzed with respect to the efficacy of the drug. Adverse effects were evaluated during and after colonoscopic examinations. Compared to these cases, 27 patients with severe colonic spasm administered intraluminal water with a small amount of dimethicone were assessed as controls. These patients were enrolled and evaluated consequently after the enrollment of all patients using l-menthol. All examinations and evaluations were performed by an expert endoscopist (N.Y.). All patients provided written informed consent for participating in the trial. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine and performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association. This study was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN-CTR) as study #UMIN000008317.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test and the chi-square test (StatView, HULINKS). Continuous variables such as patient age and tumor size were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The antispasmodic effect of l-menthol was seen in 60.0 % (39 out of 65) cases at 30 s and 70.8 % (46 out of 65) cases at 1 min after administration of l-menthol (Fig. 2). In comparison, the rates of efficacy in the controls were 22.2 % (six out of 27 cases) and 29.6 % (eight out of 27 cases) at 30 s and 1 min after administration of water, respectively. There was a significant difference about the efficacy at 30 s and 1 min between l-menthol and water (P = 0.0009, P = 0.0006). At the 5-min evaluation time point, 46.5 % (20 out of 43) of patients had effective relaxation after l-menthol administration at the same locus (Fig. 2). In controls, the rate of efficacy was 48.1 % (13 out of 27 cases) after administration of water. On evaluating the effect at a different locus, the efficacy of l-menthol was seen in 65.0 % (13 out of 20) of cases. There was no significant difference about the efficacy at 5 min between l-menthol and water. No severe side effects were seen in patients using l-menthol compared to those using water. Various characteristics of patients including age, sex, and presence of colonic diverticulum and irritable bowel syndrome were analyzed in cases with effectiveness of l-menthol, compared to cases without effectiveness of it. There were no significant differences in these two groups (Table 2). In view of age, the efficacy of l-menthol achieved in patients aged 75 years ≦ (79.3 %, 23/29) was similar to that in patients aged 75 years < (63.8 %, 23/36).

Discussion

A previous study that involved the intraluminal administration of peppermint oil showed that the mean time for the onset of its effect was 21.6 ± 15.0 s [20]. In this study, endoscopic images were taken every 10 s after the drug administration and the antispasmodic effect was seen in 88.5 % of patients. Other reports showed that the effect of peppermint oil was seen within 30 s of administration during diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopy [19]. Our results showed that that l-menthol has maximum effect on patients at 1 min after administration (70 % of patients). The efficacy in our study was lower than that of the previous study. This was probably because of the different method of evaluation of the effect of l-menthol. We defined efficacy as the arrest and prevention of spasms for 30 s, by performing detailed magnifying endoscopy and EMR that required spasm arrest. Studies that used peppermint oil to prevent spasms during barium enema showed that the drug was effective in 41.8–60.8 % of patients [21, 22]. The onset time of paralysis was reported to be 45 s and 3–4 min after intravenous and intramuscular administration of Buscopan, respectively [23]. Compared to this, intraluminal administration of l-menthol has a similar effect onset time and is more convenient to use. Several studies have shown that the effect of peppermint oil lasted for >20 min [16, 20, 22]. However, our study revealed a shorter duration of effect (<5 min) than that of other studies. This difference of results could be because of the different methods of evaluation. However, stopping of a spasm for 30 s is essential for conducting magnifying colonoscopy and therapeutic colonoscopy, hence, we believe that our method of analysis has significant clinical value.

In our study, we administered Buscopan intramuscularly or intravenously in 60 % of the cases. Endoscopists usually control spasms with additional Buscopan administration. However, this administration is not recommended in patients with low blood pressure and tachycardia. Our study showed that l-menthol was effective in patients who were previously administered Buscopan.

Subgroup analysis showed that the efficacy of l-menthol was not associated with age, sex, or the presence of diverticulum and irritable bowel syndrome. The efficacy of l-menthol achieved in patients aged <75 years was similar to that in patients aged 75 years ≦. A previous study showed that the efficacies of peppermint oil in men and patients with irritable bowel syndrome (86.4 % and 64.0 %) were lower than that in women and patients without irritable bowel syndrome (95.0 % and 91.9 %) [20]. A possible reason for this is that only a small number of patients were evaluated. These findings should be validated in the future through large prospective clinical trials.

Intraluminal administration of peppermint oil during the insertion of the colonoscopy prevented colonic spasm and was effective for routine colonoscopic examination [20]. The amount of peppermint oil that was used was 200 ml for the whole colorectum. Another study that evaluated the effectiveness of peppermint oil for routine colonoscopy showed that oral administration of peppermint oil was beneficial in terms of the time required for cecal intubation and total procedure time, reducing colonic spasm, and decreasing pain in patients during the procedure [24]. On the other hand, for barium enema, intraluminal administration of peppermint oil using a tube was reported to be effective for preventing colonic spasm and could be used instead of Buscopan [21, 22]. One study reported that the antispasmodic effect of l-menthol in the ascending colon and cecum was better than that of Buscopan [22]. In our group, Inoue et al. performed a clinical study to investigate the relationship between the suppression of l-menthol to colonic spasm and adenoma detection rate.

In the current study, we analyzed the efficacy of l-menthol in preventing colonic spasm during colonoscopic examination. Maximal efficacy was achieved in approximately 70 % of patients within 1 min of administration, and the efficacy was thought to decrease within 5 min. Our findings indicate that intraluminal administration of l-menthol is a promising method to reduce colonic spasm, perform accurate colonoscopic diagnosis, and select appropriate therapy.

Limitations

This study was a retrospective study. The number of patients (65 patients) administered l-menthol was small, and not balanced with the number of patients administered water (27 patients). Thus, patient selection could have been biased.

References

Kudo S, Hirota S, Nakajima T et al (1994) Colorectal tumours and pit pattern. J Clin Pathol 47:880–885

Tobaru T, Mitsuyama K, Tsuruta O, Kawano H, Sata M (2008) Sub-classification of Type VI pit patterns in colorectal tumors: relation to the depth of tumor invasion. Int J Oncol 33:503–508

Fu KI, Sano Y, Kato S et al (2004) Chromoendoscopy using indigo carmine dye spraying with magnifying observation is the most reliable method for differential diagnosis between non-neoplastic and neoplastic colorectal lesions: a prospective study. Endoscopy 36:1089–1093

Kaltenbach T, Sano Y, Friedland S, Soetikno R, American Gastroenterological Association (2008) American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technology assessment on image-enhanced endoscopy. Gastroenterology 134:327–340

Yoshida N, Naito Y, Inada Y et al (2012) The detection of surface patterns by flexible spectral imaging color enhancement without magnification for diagnosis of colorectal polyps. Int J Colorectal Dis 27:605–611

Yoshida N, Naito Y, Kugai M et al (2011) Efficacy of magnifying endoscopy with flexible spectral imaging color enhancement in the diagnosis of colorectal tumors. J Gastroenterol 46:65–72

Yoshida N, Hisabe T, Inada Y et al (2013) The ability of a novel blue laser imaging system for the diagnosis of invasion depth of colorectal neoplasms. J Gastroenterol 49:73–80

Saito Y, Uraoka T, Yamaguchi Y et al (2010) A prospective, multicenter study of 1111 colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissections (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 72:1217–1225

Yoshida N, Naito Y, Yagi N, Yoshikawa T (2010) Safe procedure in endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors focused on preventing complications. World J Gastroenterol 16:1688–1695

Yoshida N, Yagi N, Inada Y et al (2013) Prevention and management of complications of and training for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2013:287173

Yoshida N, Naito Y, Inada Y et al (2012) Efficacy of endoscopic mucosal resection with 0.13% hyaluronic acid solution for colorectal polyps: a randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 27:1377–1383

Duthie HL (1981) The effect of peppermint oil on colonic motility in man. Br J Surg 68:820

Hills JM, Aaronson PI (1991) The mechanism of action of peppermint oil on gastrointestinal smooth muscle: an analysis using patch clamp electrophysiology and isolated tissue pharmacology in rabbit and guinea pig. Gastroenterology 101:55–65

Hasthorn M, Ferrante J, Luchowski E et al (1988) The actions of peppermint oil and menthol on calcium channel dependent processes in intestinal, neuronal and cardiac preparations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2:101–118

Liu JH, Chen GH, Yeh HZ et al (1997) Entericcoated peppermint oil capsules in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective, randomized trail. J Gastroenterol 32:765–768

Grigoleit HG, Grigoleit P (2005) Gastrointestinal clinicsal pharmacology of peppermint oil. Phytomedicine 12:607–611

Fujishiro M, Kaminishi M, Hiki N et al (2013) Efficacy of spraying l-menthol solution during endoscopic treatment of early gastric cancer: a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Gastroentero. doi:10.1007/s00535-013-0856-4

Hiki N, Kaminishi M, Yasuda K et al (2011) Antiperistaltic effect and safety of L-menthol sprayed on the gastric mucosa for upper GI endoscopy: a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc 73:932–941

Leicester RJ, Hunt RH (1982) Peppermint oil to reduce colonic spasm during colonoscopy. Lancet 2:989

Asao T, Mochiki E, Suzuki H et al (2001) An easy method for the intraluminal administration of peppermint oil before colonoscopy and its effectiveness in reducing colonic spasm. Gastrointest Endosc 53:172–177

Sparks MJ, O’Sullivan P, Herrington AA et al (1995) Does peppermint oil relieve spasm during barium enema? Br J Radiol 68:841–843

Asao T, Kuwano H, Ide M et al (2003) Spasmolytic effect of pepper mint oil in Barium during double contrast Barium enema compared with Buscopan. Clin Radiol 58:301–305

Smith GA (1976) Hyoscine-N-butylbromide (Buscopan) as a duodenal relaxant tubeless duodenography. Acta Radiol Diagn 17:701–713

Shavakhi A, Ardestani SK, Taki M et al (2012) Premedication with peppermint oil capsules in colonoscopy: a double blind placebo-controlled randomized trial study. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 75:349–352

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Department of Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, for helping with this study.

Conflict of interest

Yoshito Itoh and Nobuaki Yagi are affiliated with AstraZeneca Co., Ltd., Eisai Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., MSD K.K., Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Fujifilm Medical Co., Ltd. and Merck Serono Co., Ltd. Yuji Naito received research grants from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Yoshito Itoh received research grants from MSD K.K. and Bristol-Myers K.K. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yoshida, N., Naito, Y., Hirose, R. et al. Prevention of colonic spasm using l-menthol in colonoscopic examination. Int J Colorectal Dis 29, 579–583 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-014-1844-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-014-1844-8