Abstract

Purpose

An association between hospital volume and postoperative mortality has been identified for several oncologic surgical procedures. Our objective was to analyze differences in surgical outcomes for patients with rectal cancer according to hospital volume in the state of California.

Methods

A cross-sectional study from 2000 to 2005 was performed using the state of California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development database. Hospitals were categorized into low (≤30)-, medium (31–60)-, and high (>60)-volume groups based on the total number of rectal cancer operations performed during the study period.

Results

Overall, 7,187 rectal cancer operations were performed. Of the 321 hospitals in the study cohort, 72 % (n = 232), 20 % (n = 65), and 8 % (n = 24) were low-, medium-, and high-volume hospitals, respectively. Postoperative mortality was significantly lower- in high-volume hospitals (0.9 %) when compared to medium- (1.1 %) and low-volume hospitals (2.1 %; p < 0.001). High-volume hospitals also performed more sphincter-preserving procedures (64 %) when compared to medium- (55 %) and low-volume hospitals (51 %; p < 0.001).

Conclusions

These data indicate that hospital volume correlates with improved outcomes in rectal cancer surgery. Rectal cancer patients may benefit from lower mortality and increased sphincter preservation in higher-volume centers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent studies have documented the relationship between hospital volume and surgical outcomes. Higher hospital volume has been linked to lower postoperative mortality and complications for a number of surgical oncology procedures [1–3] though the degree of association is subject to the specific operation being performed. For example, significant differences in mortality have been recognized for esophageal [4–6] and pancreatic resections [7–10] according to hospital volume. For colorectal cancer surgery, a volume-related effect on postoperative mortality and sphincter preservation has also been identified [11–15]. However, surgery is inherently different for rectal cancer than colon cancer and there is paucity of data regarding a volume-to-outcome relationship specifically for rectal cancer surgery.

There is ongoing national debate regarding the need to regionalize complex surgical procedures [16–19]. Although the Institute of Medicine has recommended the regionalization of esophageal and pancreatic surgery [20], no guidance currently exists for rectal cancer surgery. Given its complexities, it may be reasonable to believe that rectal cancer surgery can be performed with improved results at higher-volume institutions. As such, more data regarding rectal cancer surgery outcomes is necessary before recommendations can be proposed. The aim of this study was to determine the relationship between hospital volume and surgical outcomes in patients with rectal cancer.

Methods

OSHPD database

The state of California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) database was accessed to collect data on all California hospitals that had performed rectal cancer surgery on an elective or emergent basis between the years 2000 and 2005. OSHPD is a registry of all California hospitals that requires mandatory reporting of specific hospital outcomes. The registry was designed to collect both clinical and financial data [21–23]. Clinical data that is tracked by OSHPD include cancer diagnosis, type of surgery, length of hospital stay, hospital mortality, complications, and comorbidities.

By using the appropriate procedure code from the International Classification of Disease version 9 (ICD-9) [24], we assessed all patients diagnosed with rectal cancer (code 154.1) who underwent surgery by low anterior resection (CPT code 48.63) or abdominoperineal resection (CPT code 48.5). Patients with colon or rectosigmoid cancer were excluded. Primary outcomes measured were surgical morbidity, mortality (defined as the in hospital rate of death), and rates of sphincter-preserving surgery.

Validity of volume measure

Hospitals were ranked by volume according to the total number of operations performed between 2000 and 2005 in accordance with previously described benchmarks of categorizing hospital volume [2, 12, 13, 25]. Hospital volume was categorized as low, medium, or high depending on the total number of rectal cancer operations performed during the 6-year period. This stratification allowed for approximate equal distribution of patients into the three groups. Low-, middle-, and high-volume hospitals were defined as the completion of ≤30, 31–60, and >60 cancer operations, respectively, during the 6-year period.

Statistical analyses

Differences in length of stay between hospital volume groups were determined using an analysis of variance. For univariate analysis, a Mantel–Haenszel chi-square test with ordered categories was performed. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify differences in mortality and sphincter preservation in relation to hospital volume controlling for age, gender, race, ethnicity, and surgery type. All tests were two-sided and statistical significance was set at p = 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software program (SPSS® v. 15.0, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Demographic comparison

Using the OSHPD database, 7,187 rectal cancer operations that were performed in 321 hospitals were identified and subsequently assessed in our study. Patient characteristics were then compared after stratification into low-, medium-, and high-volume groups. We found significant differences in age, race, and ethnicity distributions among patients in each hospital volume group (Table 1). The low-volume hospitals had a significantly higher proportion of older and Hispanic patients and a significantly lower proportion of Caucasian patients.

Comparison of clinical outcomes

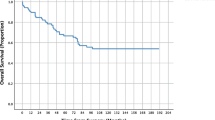

Postoperative morbidity, mortality, and rate of sphincter preservation were also compared after patients were stratified into volume groups, univariate and multivariate analysis controlling for the aforementioned differences in patient populations were then conducted. Raw data showed significantly higher mortality in low-volume hospitals (2.1 %) as compared with medium- (1.1 %) and high-volume hospital (0.9 %, p < 0.001; Table 2). Additionally, when volume groups were further stratified by deciles of hospital volume, a subset of very high volume hospitals that had much lower postoperative mortality (0.3 %) was identified. Each of these institutions performed over 120 rectal cancer operations during the 6-year study period. The potential association of demographic factors with postoperative mortality was then assessed (Table 3). High hospital volume, younger age, female gender, and sphincter-preserving procedure were significantly associated with lower mortality by univariate analysis. Hospital volume, age, and gender remained as independent prognostic factors for determining mortality by multivariate analysis (Table 3).

High-volume hospitals also performed a higher percentage of sphincter-preserving surgery (Table 2). When evaluating the relationship of demographic factors to sphincter preservation, univariate analysis identified high hospital volume, younger age, female gender, and non-Hispanic ethnicity as significant factors associated with sphincter-preserving procedures. By multivariate analysis, these aforementioned factors as well as non-White race independently predicted the performance of sphincter-preserving operations (Table 4). High-volume hospitals have lower percentage of co-morbidity about 20 % when compared with 24 and 22 % for medium- and low-volume hospital, respectively, but these results are not statistically significant.

Discussion

This analysis of the OSHPD database identified significant differences in surgical outcomes for rectal cancer in the state of California. We recognized an inverse relationship between hospital volume and postoperative mortality, though there were differences in demographic factors between hospital volume groups. This inverse relationship remained apparent after the effects of age, gender, race, ethnicity, and surgery type were controlled by multivariate analysis. Additionally, we identified a subgroup of hospitals with the highest volume (>20 rectal cancer operations per year) with the corresponding lowest overall mortality rate (0.3 %). This low mortality correlated with previously published figures worldwide. One group in Japan recorded 0 % mortality in 159 patients with rectal cancer operated upon at the Cancer Institute Hospital,over a 3-year period in Tokyo, Japan [26]. Other large rectal cancer series have reported mortality between 0 and 3 % following rectal cancer surgery [27, 28]. We also recognized a linear relationship between hospital volume and sphincter-preserving surgery. Specifically, a higher proportion of sphincter-preserving surgery was performed in high-volume centers. Surprisingly, the rate of sphincter-preserving surgeries in our study is below that reported in many other large series from around the globe. Ricciardi et al. published a large study looking at rates of sphincter-sparing surgery in the USA over time. The authors showed that most patients with rectal cancer in the USA who were treated with radical surgery between 1988 and 2003 had a colostomy. Interestingly, the proportion of sphincter-sparing procedures did increase from 26.9 % in 1988 to 48.3 % in 2003, though there has been no significant change in the rate of sphincter-sparing surgery after 1999. This study also showed that the care of rectal cancer in the USA does not achieve the quality reported by our European colleagues, where rectal cancer care has been increasingly regionalized [29]. We therefore propose that our study represents the current overall rates of sphincter-preservation in the USA, or at least in California. This rate appears to have changed little since 2002–2004 when another study done by the same author used the hospitals discharge data from 21 states across the USA. This study examined the factors that are associated with the high rate of nonrestorative proctectomy with colostomy performed in greater than 60 % of all patients with rectal cancer [30].

Comparison of volume groups revealed several notable differences and univariate and multivariate analyses identified clinical factors that were associated with inferior surgical outcomes. Elderly individuals (i.e., >65 years of age) had higher postoperative mortality and lower rates of sphincter preservation (Tables 3 and 4). We postulate that a lower rate of sphincter-preserving surgery in the elderly may reflect the surgeon’s selection of fecal diversion in patients with higher risk for fecal incontinence [31, 32].

Male gender was also associated with higher postoperative mortality and lower rates of sphincter-preserving surgery [33, 34]. These outcomes may be secondary to technically demanding low anterior resection in the male pelvis resulting in lower rates of sphincter preservation [35]. Accordingly, our study identifies hospital volume as a contributing factor to improved surgical outcomes in higher-volume institutions and implicates additional factors that may have importance in a volume-to-outcome relationship. These factors likely include other patient demographic characteristics within each hospital volume category.

Interestingly, despite the differences in mortality, there was no significant difference in surgical morbidity (P value, 0.709) when comparing the different volume groups 20, 24, and 22 % for high-, medium-, and low-volume hospital, respectively. These results are interesting but must be interpreted with some degree of caution. One explanation is that in a group with lower rates of anastomotic creation, one would expect a lower rate of anastomotic complications. Additionally, prior studies have documented the weakness of administrative data to accurately report postoperative complications when using ICD-9-CM complication codes [36, 37]. In contrast, the reporting of postoperative deaths or mortality in the OSPHD database is mandatory.

There are a limited number of studies comparing short-term surgical outcomes and their relationship to hospital volume in rectal cancer. Hodgson et al. analyzed the California Cancer Registry in patients with rectal and rectosigmoid cancers and identified improved 30-day mortality and lower colostomy rates in higher-volume institutions [15]. The results of our study corroborate this data; however, we excluded patients with rectosigmoid cancers because the inherent risks of surgical morbidity and mortality are distinctly less than for rectal cancers. In contrast, a study by Schrag et al., utilizing the SEER-Medicare database did not identify a statistical difference in 30-day mortality according to hospital volume in patients greater than 65 years of age [13]. Their disparate results may be secondary to a smaller cohort of patients who were also age restricted according to Medicare criteria.

Our study does have limitations inherent to use of the OSHPD database. Given its administrative nature, the database does not allow for true risk stratification. As such, the comparisons of co-morbidities were absent which may limit the subsequent comparisons in patient mortality. Furthermore, OSHPD does not collect clinical data such as tumor size, stage, tumor distance from the anal sphincter, or the use of adjuvant radiation or chemotherapy all of which may impact the selection of a sphincter-preserving procedure. Additionally, surgeon-specific volume could not be evaluated in this study given the database limitations. However, hospital volume alone appears to be an appropriate surrogate for surgeon volume in colorectal resections [38].

In conclusion, our study suggests that high-volume centers have improved outcomes for rectal cancer surgery regarding lower mortality and increase rates of sphincter-preserving surgery. However, additional studies are necessary to fully categorize clinical and pathologic factors that may impact differences in outcome.

References

Begg CB, Cramer LD, Hoskins WJ, Brennan MF (1998) Impact of hospital volume on operative mortality for major cancer surgery. JAMA 280:1747–1751

Finlayson EV, Goodney PP, Birkmeyer JD (2003) Hospital volume and operative mortality in cancer surgery: a national study. Arch Surg 138:721–725, discussion 726

Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finalyson EVA, Stukel TA (2002) Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. Engl J Med 346:1128–1137

Swisher SG, DeFord L, Merriman KW (2000) Effect of operative volume on morbidity, mortality, and hospital use after esophagectomy for cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 119:1126–1134

Atkins BZ, Shah AS, Hutcheson KA (2004) Reducing hospital morbidity and mortality following esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 78:1170–1176

Kuo WY, Chang Y, Wright CD (2001) Impact of hospital volume on clinical and economic outcomes for esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 72:1118

Van Heek NT, Kuhlmann KFD, Scholten RJ (2005) Hospital volume and mortality after pancreatic resection a systematic review and an evaluation of intervention in the Netherlands. Ann Surg 242:781–790

Birkmeyer JD, Warshaw AL, Finlayson SR, Grove MR, Tosteson AN (1999) Relationship between hospital volume and late survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery 126:178–183

Birkmeyer JD, Finlayson SR, Tosteson AN, Sharp SM, Warshaw AL, Fisher ES (1999) Effect of hospital volume on in-hospital mortality with pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery 125:250–256

Gouma DJ, Van Geenen RC, Van Gulik TM, De Haan RJ, De Wit LT (2000) Rates of complications and death after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg 232(6):786–795

Schrag D, Cramer LD, Bach PB, Cohen AM, Warren JL, Begg CB (2000) Influence of hospital procedure volume on outcomes following surgery for colon cancer. JAMA 284:3028–3035

Rogers SO Jr, Wolf RE, Zaslavsky AM, Wright WE, Ayanian JZ (2006) Relation of surgeon and hospital volume to processes and outcomes of colorectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg 244:1003–1011

Schrag D, Panageas KS, Riedel E, Cramer LD, Guillem JG, Bach PB, Begg CB (2002) Hospital and surgeon procedure volume as predictors of outcome following rectal cancer resection. Ann Surg 236:583–592

Meyerhardt JA, Tepper JE, Niedzwiecki D et al (2004) Impact of hospital procedure volume on surgical operation and long-term outcomes in high-risk curatively resected rectal cancer: findings from the Intergroup 0114 Study. J Clin Oncol 22:166–174

Hodgson DC, Zhang W, Zaslavsky AM, Fuchs CS, Wright WE, Ayanian JZ (2003) Relation of hospital volume to colostomy rates and survival for patients with rectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 95:708–716

Birkmeyer JD, Lucas FL, Wennberg DE (1999) Potential benefits of regionalizing major surgery in Medicare patients. Eff Clin Pract 2:277–283

Birkmeyer JD (2000) Should we regionalize major surgery? Potential benefits and policy considerations. J Am Coll Surg 190:341–349

Birkmeyer JD, Finlayson EV, Birkmeyer CM (2001) Volume standards for high-risk surgical procedures: potential benefits of the Leapfrog initiative. Surgery 130:415–422

Finlayson SR, Birkmeyer JD, Tosteson AN, Nease RF Jr (1999) Patient preferences for location of care: implications for regionalization. Med Care 37:204–209

Hewitt M, Petitti D (2001) Interpreting the volume—outcome relationship in the context of cancer care. The National Academies Press, Washington

Romano PS, Zach A, Luft HS, Rainwater J, Remy LL, Campa D (1995) The California Hospital Outcomes Project: using administrative data to compare hospital performance. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 21:668–682

Hoisington R, OSHPD (1992) (Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development) to implement fully automated plan review. Calif Hosp 6:18–36

Buchmueller TC, Allen ME, Wright W (2003) Assessing the validity of insurance coverage data in hospital discharge records: California OSHPD data. Health Serv Res 38:1359–1372

The International Classification of Diseases (1998) 9th revision, clinical modification: ICD-9. GPO, Washington

Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV (2002) Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 346:1128–1137

Kuroyanagi H, Akiyoshi T, Oya M, Fujimoto Y, Ueno M, Yamaguchi T, Muto T (2009) Laparoscopic-assisted anterior resection with double-stapling technique anastomosis: safe and feasible for lower rectal cancer? Surg Endosc 23:2197–2202

Laurent C, Leblanc F, Wütrich P, Scheffler M, Rullier E (2009) Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer long-term oncologic results. Ann Surg 250(1):54–61

Paun BC, Cassie S, MacLean AR et al (2010) Postoperative complications following surgery for rectal cancer. Ann Surg 251:807–818

Ricciardi R, Virnig BA, Madoff RD, Rothenberger DA, Baxter NN (2007) The status of radical proctectomy and sphincter-sparing surgery in the United States. Dis Colon Rectum 50:1119–1127

Ricciardi R, Roberts PL, Read TE, Baxter NN, Marcello PW, Schoetz DJ (2011) Presence of specialty surgeons reduces the likelihood of colostomy after proctectomy for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 54:207–213

Graf W, Ekstrom K, Glimelius B, Pahlman L (1996) A pilot study of factors influencing bowel function after colorectal anastomosis. Dis Colon Recum 39:744–749

Chatwin NA, Ribordy M, Givel JC (2002) Clinical outcomes and quality of life after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Eur J Surg 168(5):297–301

Poon RT, Chu K, Ho JW, Chan CW, Law WI (1999) Preserving surgery prospective evaluation of selective defunctioning stoma for low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision. World J Surg 23:463–468

Petersen S, Freitag M, Hellmich G, Ludwig K (1998) Anastomotic leakage: impact on local recurrence and survival in surgery of colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 13:160–163

Law WI, Chu KW, Ho JW, Chan CW (1998) Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision (2000). Am J Surg 179:92–96

Romano PS, Schembri ME, Rainwater JA (2002) Can administrative data be used to ascertain clinically significant postoperative complications? Am J Med Qual 17:145–154

Romano PS, Chan BK, Schembri ME, Rainwater JA (2002) Can administrative data be used to compare postoperative complication rates across hospitals? Med Care 40:856–867

Harmon JW, Tang DG, Gordon TA (1999) Hospital volume can serve as a surrogate for surgeon volume for achieving excellent outcomes in colorectal resection. Ann Surg 230:404–411

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Robert Hawks, BS, for his assistance with the OSHPD database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Jeong-Heum Baek and Abdulhadi Alrubaie contributed equally to this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baek, JH., Alrubaie, A., Guzman, E.A. et al. The association of hospital volume with rectal cancer surgery outcomes. Int J Colorectal Dis 28, 191–196 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-012-1536-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-012-1536-1