Abstract

Aim

An illustration of the diagnosis and management of tailgut cysts.

Materials and methods

Two cases of tailgut cyst and a review of the literature.

Results

A female patient presented with acute urinary retention with a retrorectal mass felt during rectal examination and confirmed on ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging underwent surgical resection and histology confirmed a chronically inflamed mucoid fluid-filled cyst partly lined by non-keratinised squamous epithelium. A male patient with ureteric obstruction and a prerectal cyst found on ultrasound scan underwent computed tomography with biopsies, but without reaching a conclusive diagnosis. Surgical resection was carried out and histology showed a chronically inflamed mucoid fluid-filled cyst partly lined with columnar epithelium.

Discussion

Tailgut cysts are a rare developmental abnormality arising from remnants of the embryological postanal gut. Usually presenting incidentally or with pressure symptoms in middle-aged females, tailgut cysts are often initially mistaken for other clinical entities. Magnetic resonance imaging helps to differentiate tailgut cysts from other retrorectal lesions and developmental cysts. Histologically, the cyst wall demonstrates a wide variety of epithelial types and has a malignant potential. Malignancy is difficult to rule out with imaging or biopsy.

Conclusions

Magnetic resonance imaging is the favoured imaging modality and surgical resection is recommended to relieve pressure symptoms, provide a definitive diagnosis and rule out malignancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Tailgut cysts, also known as retrorectal cystic hamartomas and mucus-secreting cysts, are rare congenital lesions that are thought to be derived from remnants of the embryonic postanal gut, which incompletely regresses during development [1–3].

They are almost invariably located in the retrorectal space [2], but have also been reported in the perirenal space [4–6], the perianal skin [3, 7–9] and, very rarely, prerectally [2, 10, 11]. We present a retrorectal tailgut cyst and also a much rarer prerectal tailgut cyst, which has only been reported four times before.

Case reports

Case 1

History and examination

A 24-year-old female presented to the Accident and Emergency Department with acute urinary retention requiring urethral catheterisation. She gave a 2-year history of low backache, but had no abdominal or anal symptoms. One year previously, she had a thyroidectomy for a follicular adenoma. Clinical examination of the abdomen revealed a pelvic mass and digital rectal examination revealed a smooth, large, immobile retrorectal mass displacing the rectum to the right-hand side. It was not possible to get above the mass on rectal examination.

Investigations

Initial investigation with transabdominal ultrasonography confirmed a pelvic mass. Computed tomography (CT) with contrast demonstrated a low attenuation lesion in the retrorectal space. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast confirmed a 9 × 11 × 11-cm cystic mass in the retrorectal space (Fig. 1), displacing the rectum, anal canal and distal sigmoid to the right and the vagina anteriorly. The cyst was well-defined, thin-walled, unilocular and extended into the right ischioanal fossa. The cyst was adherent to the left posterolateral wall of the rectum, but did not invade the sacrum. On T1-weighted MRI, the lesion was low signal and, on T2-weighted MRI, the lesion was high signal. There were no areas of heterogeneity or irregularity that enhanced with contrast.

Treatment

The patient underwent a low anterior resection with a hand-sewn coloanal anastomosis and loop ileostomy. The retrorectal cyst was excised completely (Fig. 2). Postoperative recovery was complicated by a left ischioanal fossa collection secondary to a contained leak from the coloanal anastomosis. This required two CT-guided percutaneous drainages. The patient then made a good recovery. A gastrograffin enema, at 3 months postoperatively, showed no leak from the coloanal anastomosis and the patient had uncomplicated ileostomy closure.

Histopathology

On histopathological examination, the macroscopic specimen consisted of a unilocular 11 × 6.5 × 4-cm collapsed cyst attached to the posterior mesorectal surface by a 3 × 2-cm stalk of connective tissue. The inner aspect of the cyst had an irregular, yellow surface with some mucoid fluid content (Fig. 2).

Microscopically, the cyst was partially lined by non-keratinising squamous epithelium (Fig. 3). In other areas, it was lined by granulation tissue with numerous foamy macrophages, scattered foreign body type multinucleated giant cells and cholesterol crystals. The underlying stroma showed chronic inflammation and fibrosis.

Case 2

History and examination and investigations

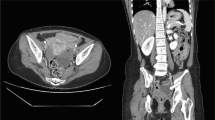

A 60-year-old gentleman, with a past medical history of idiopathic epilepsy, had an abdominal ultrasound scan for the investigation of very mildly deranged liver function tests. The ultrasound scan coincidentally detected a pelvic cystic mass and left-sided hydronephrosis. Abdominal and digital rectal examinations were unremarkable. A subsequent CT scan with contrast revealed a partially calcified, lobulated cystic mass situated posterior to the bladder and anterior to the rectum. The cyst displaced the bladder to the right and was extrinsically compressing the distal left ureter causing left hydronephrosis (Fig. 4). The differential diagnosis based on the CT scan included a large bladder diverticulum with tumour within it or a tumour of the seminal vesicles or prostate. However, a transrectal ultrasound scan showed the lesion was not arising from the seminal vesicles or prostate and cystoscopy demonstrated that the bladder was normal. Percutaneous needle biopsy of the cyst was inconclusive, showing only mucinous and inflammatory material with no malignant cytology.

Management

The patient was managed with the insertion of a JJ stent at cystoscopy to relieve the left-sided hydronephrosis. Laparotomy revealed an anterior-rectal cystic lesion, adherent to both ureters and to the small bowel and rectum. Frozen section of the cyst wall was inconclusive showing only inflammatory cells. An anterior resection and defunctioning ileostomy was performed and the patient made an uneventful recovery.

Histopathology

On histopathological examination, the macroscopic specimen consisted of a unilocular collapsed cyst attached to the posterior mesorectal surface. The inner aspect of the cyst had an irregular, yellow surface with mucoid fluid content.

Microscopic examination of the cyst wall showed mucinous columnar epithelium with denuded areas lined with foamy macrophages and scattered regions of fibrotic connective tissue associated with multinucleated foreign body giant cells with cholesterol clefts. There was no bowel mucosa, organised smooth muscle layers or neural plexus (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Origin

Tailgut cysts are believed to arise from the remnants of the embryonic hindgut. During the 3.5- to 8-mm gestational stage (28–35 days) of human development, the embryo possesses a true tail, which is caudal to the site of the subsequent formation of the anus. The primitive hindgut extends into this tail, which usually completely regresses by the eighth week of gestation [12]. The persistence of this postanal gut in the retrorectal space is hypothesised to be the origin of the tailgut cyst [1, 2].

Clinical features

Tailgut cysts predominantly present in middle-aged women with an average age of 35 and a male to female ratio of approximately 1:3 [2, 13, 14]. Tailgut cyst has been described in infants and in the foetus, strengthening the theory that it is a congenital condition [3, 15].

Symptoms of mass effect or pain are present in 50% and include rectal fullness, bleeding and pain on defaecation, constipation, lower abdominal and back pain and symptoms associated with genitourinary obstruction [2, 13, 16].

Misdiagnosis and infection

A large proportion of cases are initially misdiagnosed. The patient may present with a history of multiple drainage procedures for recurrent pilonidal abscess, perianal abscess or fistula in ano [2].

Examination and locations

On digital rectal examination, a mass is usually palpable in the retrorectal space [2]. However, few cases have been reported showing that tailgut cysts can occupy other positions in the perirenal space [4–6], the perianal skin [3, 7–9] and prerectally [2, 10, 11].

Malignancy

Cases of malignancies that have been reported to be associated with a tailgut cyst include adenocarcinomas, carcinoid tumours, neuroendocrine carcinomas, endometrioid carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and sarcoma. The majority are adenocarcinomas and carcinoid tumours [2, 9, 13, 14, 17–24].

Dysplasia

Adenocarcinomas arising from tailgut cysts may have p53 gene mutations similar to colorectal adenocarcinoma. These cysts also demonstrated dysplasia, suggesting a dysplasia–carcinoma sequence [19].

Tumour markers

Adenocarcinoma arising in a tailgut cyst has occasionally been shown to be positive for CEA and serum CEA and CA19.9. Tumour markers that have been shown to indicate tailgut cyst tumour recurrence [18, 20, 21, 25].

Radiological features

Localisation

Localisation of the cyst in the retrorectal space may be difficult with transabdominal ultrasound and can be mistaken for an adnexal mass [26]; however, it may reveal whether the cyst is unilocular or multilocular.

Transrectal ultrasound may be useful in demonstrating the integrity of the layers of the rectum, showing absence of invasion in a benign lesion [27]. Cross-sectional imaging techniques are more reliable at defining the location of the cyst in the retrorectal space [26].

Differential diagnosis of retrorectal cyst

When the location of a retrorectal cyst is known there is still a large radiological differential diagnosis; epidermoid cyst, dermoid cyst, rectal duplication, neuroenteric cysts, cystic sacrococcygeal teratoma, anterior sacral meningocele, necrotic rectal leiomyosarcoma, extraperitoneal adenomucinosis, cystic lymphangioma, pyogenic abscess, neurogenic cyst, necrotic sacral chordoma and tailgut cyst [14].

A prerectal cyst differential diagnosis includes utricle cyst of the prostate, simple cyst of the prostate, rectal duplication, simple cyst of the seminal vesicle and bladder diverticulum [11, 28, 29].

CT

CT usually demonstrates a thin-walled, well-circumscribed retrorectal mass with septations. When the mass is large, the rectum may be displaced. The low attenuation of the contents varies according to the consistency of mucin and inflammatory debris [26, 30].

Calcifications may be seen in the cyst wall although they are more commonly a feature seen in dermoid cysts, teratoma and other retrorectal space lesions (e.g. neuroblastoma, chordoma and mucinous adenocarcinoma) [24, 26, 31].

Infection may cause wall thickening along with other signs of local inflammation. Invasion of adjacent structures and loss of discrete margins are important signs of malignancy [26, 30].

MRI

Tailgut cysts usually have a low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images [32, 33].

MRI is more sensitive than CT at differentiating unilocular and multilocular masses and especially for the detection of small peripheral cysts [33]. The cyst wall and septa usually enhance with gadolinium, as do areas of malignant transformation and infection. Malignancy is suspected if there is a heterogeneous thickening with an irregular margin, invasion into the pelvic sidewall or adjacent pelvic viscera and intermediate signal before contrast on both T1- and T2-weighted images with enhancement after contrast [20, 23, 31, 32]. Recurrent benign tumours may be heterogeneous and have irregular margins and be indistinguishable from malignancy [34].

Histopathological features

Tailgut cyst

The histopathological features that help differentiate tailgut cysts from the other types of developmental cysts are the cell types in the lining of the cyst.

Gross examination of a tailgut cyst usually reveals a multilocular cyst ranging in size from 1 to 15 cm with a clear, thick mucoid fluid content. The cyst wall can be lined by a variety of epithelia: stratified squamous, columnar, cuboidal, ciliated columnar, mucinous, gastric and transitional. Scattered bundles of smooth muscle fibres are usually present in the cyst wall separated from the epithelium by a thin layer of fibrous tissue [2, 13, 14].

Other types of retrorectal/developmental cyst

Epidermoid cysts are unilocular and lined with stratified squamous epithelium and contain clear fluid. Dermoid cysts are similar to epidermoid cysts, but also contain skin appendages (e.g. hair follicles, sweat glands). Rectal duplication is defined by three histological criteria: continuity with the rectum, a smooth muscle coat with myenteric plexus and a mucosal lining reflective of the gastrointestinal tract with muscularis mucosae, villi and crypts. Teratomas contain derivatives from all three embryonic germ cell layers: ectoderm (squamous epithelium and skin appendages), endoderm (respiratory or gastrointestinal epithelium and pancreas) and mesoderm (connective tissue, smooth muscle, cartilage and bone). Neuroenteric cysts differ from tailgut cyst in that they contain a well-defined lamina propria and a more mature mucosa of endodermal origin (e.g. intestinal, bladder) [2, 13, 14, 31].

Teratoma

It has been suggested that tailgut cysts may be classified as teratomas because they contain evidence of ectoderm (squamous epithelium), endoderm (respiratory ciliated epithelium) and mesoderm (smooth muscle) [13, 25]. However, the ciliated columnar epithelium may have persisted from the embryological gastrointestinal tract and squamous epithelium may be due to metaplasia [2].The term teratoma is reserved for cysts demonstrating dermal appendages, neural elements, cartilage or bone [14].

Differential diagnosis of a prerectal cyst

The differential diagnosis of prerectal tailgut cyst includes: rectal duplication, utricle cyst of the prostate, which is lined by columnar or cuboidal epithelium and continuous with the utricular wall [35], and simple cyst of the seminal vesicle, which is lined by cuboidal or squamous epithelium with a fibrous wall and sperm within [11].

Management

All retrorectal cysts should be assessed for malignancy with radiological imaging and biopsy for histology. Unfortunately, definitive diagnosis and particularly differentiation of tailgut cysts from the other developmental cysts is usually not possible on diagnostic biopsies, including needle biopsy and frozen sections, as was the case in the second of our patients. Although diagnosis has been reported with ultrasound-guided needle biopsy [36], a diagnostic biopsy is generally not advised because it may miss foci of malignancy. Even if the biopsy does sample a malignancy, it carries the risk of spillage and seeding of tumour cells [14].

If there is a low index of suspicion for malignancy and patients are asymptomatic, routine surveillance may be appropriate. However, surgical resection provides a specimen that is sufficient for histopathological examination to give a definitive diagnosis, relieves symptoms caused by mass effect, avoids subsequent infection and rules out malignant transformation.

Conclusion

The preoperative diagnosis depends primarily on correct localisation of the cyst, which is usually in the retrorectal space, this is most accurately provided by MRI. The recommended treatment is complete surgical excision to provide a definitive diagnosis, relieve symptoms and exclude malignancy.

References

Middeldorpf K (1885) Zur kenntniss der angbornen sacralgeschwulst. Virchows Arch 101:37–44

Hjermstad BM, Helwig EB (1988) Tailgut cysts. report of 53 cases. Am J Clin Pathol 89(2):139–147 (Feb)

Rafindadi AH, Shehu SM, Ameh EA (1998) Retrorectal cystic harmatoma (tailgut cyst) in an infant: case report. East Afr Med J 75(12):726–727 (Dec)

Sung MT, Ko SF, Niu CK, Hsieh CS, Huang HY (2003) Perirenal tailgut cyst (cystic hamartoma). J Pediatr Surg 38(9):1404–1406 (Sep)

Kang JW, Kim SH, Kim KW, Moon SK, Kim CJ, Chi JG (2002) Unusual perirenal location of a tailgut cyst. Korean J Radiol 3(4):267–270 (Oct–Dec)

Mills SE, Walker AN, Stallings RG, Allen MS Jr (1984) Retrorectal cystic hamartoma. Report of three cases, including one with a perirenal component. Arch Pathol Lab Med 108(9):737–740 (Sep)

Murao K, Fukui Y, Numoto S, Urano Y (2003) Tailgut cyst as a subcutaneous tumor at the coccygeal region. Am J Dermatopathol 25(3):275–277 (Jun)

Sidoni A, Bucciarelli E (1997) Ciliated cyst of the perineal skin. Am J Dermatopathol 19(1):93–96 (Feb)

Song DE, Park JK, Hur B, Ro JY (2004) Carcinoid tumor arising in a tailgut cyst of the anorectal junction with distant metastasis: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 128(5):578–580 (May)

Gips M, Melki Y, Wolloch Y (1994) Cysts of the tailgut. two cases. Eur J Surg 160(8):459–460 (Aug)

Jang SH, Jang KS, Song YS, Min KW, Han HX, Lee KG et al (2006) Unusual prerectal location of a tailgut cyst: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 12(31):5081–5083 (Aug 21)

Caropreso PR, Wengert PA Jr, Milford HE (1975) Tailgut cyst—a rare retrorectal tumor: report of a case and review. Dis Colon Rectum 18(7):597–600 (Oct)

Prasad AR, Amin MB, Randolph TL, Lee CS, Ma CK (2000) Retrorectal cystic hamartoma: report of 5 cases with malignancy arising in 2. Arch Pathol Lab Med 124(5):725–729 (May)

Gonul II, Baglan T, Pala I, Mentes B (2007) Tailgut cysts: diagnostic challenge for both pathologists and clinicians. Int J Colorectal Dis 22(10):1283–1285 (Oct)

Nakagawa M, Hara M, Oshima H, Kitase M, Shibamoto Y (2008) Radiological findings of tailgut cyst in a fetus. J Comput Assist Tomogr 32(2):210–213 (Mar–Apr)

Sriganeshan V, Alexis JB (2006) A 37-year-old woman with a presacral mass. tailgut cyst (retrorectal cystic hamartoma). Arch Pathol Lab Med 130(5):e77–e78 (May)

Kanthan SC, Kanthan R (2004) Unusual retrorectal lesion. Asian J Surg 27(2):144–146 (Apr)

Schwarz RE, Lyda M, Lew M, Paz IB (2000) A carcinoembryonic antigen-secreting adenocarcinoma arising within a retrorectal tailgut cyst: clinicopathological considerations. Am J Gastroenterol 95(5):1344–1347 (May)

Moreira AL, Scholes JV, Boppana S, Melamed J (2001) p53 mutation in adenocarcinoma arising in retrorectal cyst hamartoma (tailgut cyst): report of 2 cases—an immunohistochemistry/immunoperoxidase study. Arch Pathol Lab Med 125(10):1361–1364 (Oct)

Maruyama A, Murabayashi K, Hayashi M, Nakano H, Isaji S, Uehara S et al (1998) Adenocarcinoma arising in a tailgut cyst: report of a case. Surg Today 28(12):1319–1322

Cho BC, Kim NK, Lim BJ, Kang SO, Sohn JH, Roh JK et al (2005) A carcinoembryonic antigen-secreting adenocarcinoma arising in tailgut cyst: clinical implications of carcinoembryonic antigen. Yonsei Med J 46(4):555–561 (Aug 31)

Moulopoulos LA, Karvouni E, Kehagias D, Dimopoulos MA, Gouliamos A, Vlahos L (1999) MR imaging of complex tail-gut cysts. Clin Radiol 54(2):118–122 (Feb)

Aflalo-Hazan V, Rousset P, Mourra N, Lewin M, Azizi L, Hoeffel C (2008) Tailgut cysts: MRI findings. Eur Radiol (in press)

Liessi G, Cesari S, Pavanello M, Butini R (1995) Tailgut cysts: CT and MR findings. Abdom Imaging 20(3):256–258 (May–Jun)

Andea AA, Klimstra DS (2005) Adenocarcinoma arising in a tailgut cyst with prominent meningothelial proliferation and thyroid tissue: case report and review of the literature. Virchows Arch 446(3):316–321 (Mar)

Menassa-Moussa L, Kanso H, Checrallah A, Abboud J, Ghossain M (2005) CT and MR findings of a retrorectal cystic hamartoma confused with an adnexal mass on ultrasound. Eur Radiol 15(2):263–266 (Feb)

Hutton KA, Benson EA (1992) Case report: tailgut cyst—assessment with transrectal ultrasound. Clin Radiol 45(4):288–289 (Apr)

Nghiem HT, Kellman GM, Sandberg SA, Craig BM (1990) Cystic lesions of the prostate. Radiographics 10(4):635–650 (Jul)

Arora SS, Breiman RS, Webb EM, Westphalen AC, Yeh BM, Coakley FV (2007) CT and MRI of congenital anomalies of the seminal vesicles. AJR Am J Roentgenol 189(1):130–135 (Jul)

Johnson AR, Ros PR, Hjermstad BM (1986) Tailgut cyst: diagnosis with CT and sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 147(6):1309–1311 (Dec)

Dahan H, Arrive L, Wendum D, Docou le Pointe H, Djouhri H, Tubiana JM (2001) Retrorectal developmental cysts in adults: clinical and radiologic–histopathologic review, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Radiographics 21(3):575–584 (May–Jun)

Lim KE, Hsu WC, Wang CR (1998) Tailgut cyst with malignancy: MR imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 170(6):1488–1490 (Jun)

Yang DM, Park CH, Jin W, Chang SK, Kim JE, Choi SJ et al (2005) Tailgut cyst: MRI evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 184(5):1519–1523 (May)

Woodfield JC, Chalmers AG, Phillips N, Sagar PM (2008) Algorithms for the surgical management of retrorectal tumours. Br J Surg 95(2):214–221 (Feb)

Kato H, Komiyama I, Maejima T, Nishizawa O (2002) Histopathological study of the mullerian duct remnant: clarification of disease categories and terminology. J Urol 167(1):133–136 (Jan)

Hall DA, Pu RT, Pang Y (2007) Diagnosis of foregut and tailgut cysts by endosonographically guided fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol 35(1):43–46 (Jan)

Acknowledgements

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Au, E., Anderson, O., Morgan, B. et al. Tailgut cysts: report of two cases. Int J Colorectal Dis 24, 345–350 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-008-0598-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-008-0598-6