Abstract

Background and objectives

Rectovaginal fistulas (RVF) in Crohn’s disease continue to be a challenging problem. Several operations are often necessary to attain definitive healing of the disease process. There are no guidelines concerning optimal therapeutic approaches. Endoanal mobilization techniques such as the advancement flap technique were considered the therapy of choice for many years, but are now regarded ever more critically. We have implemented several less aggressive closure techniques that take account of the anatomy and morphology of the anorectum. The long-term results are presented in this paper.

Materials and methods

The method used was observational analysis with a standard protocol of all patients with RVF and Crohn’s disease treated surgically at a single institution.

Results/Findings

Between January 1985 and December 2002, we treated 72 patients with low rectovaginal fistulas. The operations comprised 56 procedures performed in 37 women presenting with RVF. The patients’ median age was 34.6 ± 10 years; the follow-up period was 7.15 years (10 months–18 years). Several techniques were performed: transverse transperineal repair (n = 20), endoanal direct closure multilayer without flap (n = 15), anocutaneous flap (n = 14), and advancement mucosal or full-thickness flap (n = 7). Diverting ileostomies were created in 28 patients (76%). Recovery was achieved with the initial repair in 19 patients (51.4%). An additional 12 patients underwent repeat procedures (2–5), with an overall success rate of 27:37 (73%). The rate of recurrence was 30% during a follow-up period of 7.1 years. The rate of proctectomy was 13.5%. The success rates for each of the techniques in the above group were 70, 73, 86, and 29%, respectively. They were significantly higher with the direct closure and anocutaneous flap technique than with the advancement flap technique. However, the transperineal repair led to decreased postoperative resting pressures. In the advancement flap technique, the resting and squeezing pressure decreased significantly. The risk of developing a suture line dehiscence leading to a persisting fistula was higher in the advancement flap procedure with 43%.

Interpretation/conclusion

Techniques with a low degree of tissue mobilization such as the direct closure and anocutaneous flap show higher success rates without significant postoperative changes in continence and manometric outcome. Impaired continence was observed only in the advancement flap group, resulting in significant changes in manometric values and recovery rates. The authors prefer to apply the direct multilayer closure technique without flap.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Twenty to thirty percent of the patients with Crohn’s disease develop an anal or rectovaginal fistula in the course of their lives. The fistula may subsequently demonstrate varying levels of activity and progression, which can have crucial effects on the patients’ future. Approximately, every tenth patient with Crohn’s disease will suffer from a rectovaginal fistula [1]. Surgical therapy of anal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease is still a matter of controversy [2–7]. However, many authors recommend it for the treatment of rectovaginal fistulas [5, 8–14]. In the last 20 years, several working groups have repeatedly advocated endoanal closure implementing a flap after excision of the fistula tract as a simple, sphincter-preserving procedure that is safe to use. This flap was mostly constructed from mucosa–submucosa and parts of the circular muscles (mucosal advancement flap) [5, 14–18]. Others implemented a full-thickness flap [11, 13, 19, 20]. Although the initial reports for the treatment of crypto-glandular fistulas, as well as for Crohn fistulas, were generally positive [15, 19, 21–24]; the results published in recent years indicate that there are severe disadvantages to using the flap techniques [13, 14, 25–27]. Also, high rates of incontinence have been reported after flap techniques [26, 27].

Our experience indicates that endoanal mobilization is a relatively aggressive treatment entailing the danger of flap retraction or poor blood supply with the development of stress on the suture.

This may lead to muscular suture line dehiscence, which decisively influences the risk of a recurrence [28–30]. Taking all this into consideration, we have now been attempting for years to alter the concept of fistula surgery to achieve an effective closure without extensive tissue mobilization [31, 32]. On the basis of our own experience in crypto-glandular fistula surgery, we have attempted to implement more conservative closure techniques, extending this principle to the treatment of Crohn fistulas. The present paper reports the clinical and functional results obtained with four closure techniques using different endoanal mobilization procedures.

Materials and methods

Study and follow-up data

Our study is an observational study. A standardized fistula protocol comprised the following data:

-

History of Crohn’s disease and endoscopy data

-

Localization of the vaginal fistula ostium and the distance from introitus and localization of the intra-anal fistula ostium and its spatial relationship to the dentate line

-

Anorectal manometry

-

Endoscopic data

-

Continence data

Continence data

Our internal continence score system was replaced with an international incontinence score system in 1994 [33]. A continence grading scale comprised the following aspects of incontinence: solid, liquid, gas, pad usage, and lifestyle alteration. The frequency of each disturbance was given a point value between 0=never and 4=always. Adding up the individual points, the number 0 indicated completely continent and the number 20 total incontinence.

After discharge from the hospital, 34 patients came to the outpatient clinic for repeated further treatment on a regular basis. We asked the patients who had taken part in the study to present once again at the outpatient clinic for an additional follow-up examination. Information from three patients was obtained by contacting the patients by phone or by speaking to their treating physicians.

General patient data

Between January 1985 and December 2002, 72 women with rectovaginal fistulas and Crohn’s disease were treated at our clinic. A fistula operation was carried out in 37 patients (51.4%). In 16 patients (22.2%), the symptoms were minimal, or we set up local abscess drainage or a suture drain. We performed a loop ileostomy in symptomatic cases. In another patient group comprising 19 patients (26.4%), we implemented a primary ano-proctocolectomy/proctectomy without a prior attempt to repair the rectovaginal fistula. The patient cohort in this study comprised 37 patients with a symptomatic rectovaginal fistula that was treated surgically. The average age of the patients was 34.6 ± 10 years [27–52]. A total of 56 operations were performed. In all 37 patients, Crohn’s disease was confirmed histologically and/or endoscopically. The medical history revealed a remarkable duration of Crohn’s disease. In this group, the time range was 0.5 to 20 years (mean, 9.9 years); before the initial repair, the fistula had been present for 3 months to 6 years (mean, 2.15 years). Three patients (8%) received a low-dose hydrocortisone treatment of <10 mg/day perioperatively. Immunomodulators were administered neither at the time of the operation nor in the follow-up period.

Previous treatment

In the 37 patients with a rectovaginal fistula, surgery had already been performed to treat a perianal or anovaginal abscess in 18 patients (49%), a perianal fistula in 16 patients (44%; 9 transsphincteric, 2 intersphincteric, and 5 non-classifiable fistulas), and a rectovaginal fistula in 8 patients (22%). The average numbers of operations per patient were 1.6 for the abscess operations and 1.4 for the fistula operations. Fourteen of the patients with an anal/perianal fistula were treated surgically at our clinic. In nine of these patients, there was a transsphincteric fistula, in which 12 endoanal closure techniques were implemented.

In 12 patients (32%), a loop ileostoma was present at the time of operation. In eight patients (22%), an ileum or a colon resection had been performed previously: four ileocolic resections, two partial ileal resections, and two subtotal colectomies.

Indication, selection, and types of surgical procedures

Four different methods of repair were used, including transverse transperineal repair with levatorplasty (n = 20), endoanal direct closure without a flap (n = 15), anocutaneous flap (n = 14), and a mucosal or full-thickness flap (n = 7). In three patients with an anterior sphincter repair and levatorplasty, we synchronously operated on a perianal fistula at the same time. In another three patients, we carried out an abdominal colectomy (subtotal, sigmoid resection, proctectomy) and performed a colo-anal anastomosis and an ileo-cecal resection. In 16 out of a total of 28 patients with a loop ileostomy, the ileostomy had been performed at the time of the fistula operation. The types of fistulas were comparable in terms of localization and size with the different methods. The transperineal procedure was chosen in anatomical conditions such as supra-anal stenosis or minor inflammatory process in the rectum.

A transperineal approach was generally used in the following cases: intra-anal and supra-anal stenosis, destruction of the sphincter with incontinence, inflammation of the rectum, mucosal fibrotic scarring with reduced rectal distensibility, and a relatively large fistula opening. The surgical technique is straightforward, and there is no mobilization of the rectum wall or of the sphincters. This is a variant on the direct closure technique.

Whenever the rectum was more or less free of signs of inflammation, mucosal or full-thickness flap techniques were implemented, whereby the direct closure has been employed most often in the last few years. We have consequently been consistently using internal quality controls for years, and these have led to strategic changes in the surgical treatment of fistulas [31, 32].

The anocutaneous flap was only implemented when the anoderm was free of inflammation. Anocutaneous flap and the direct closure technique has been used at our clinic in the last 10 years.

A loop ileostomy was chosen in the following circumstances: colectomy in the history, rectal disease, immunosuppressive therapy, recurrent fistula, synchronous operations (sphincter repair, colectomy, and anal fistulectomy), and a large fistula opening.

Definitions

-

Rectal involvement.

-

Minimal: histologic changes only

-

Active: focal macroscopic changes confined to the distal rectum without mucosal ulcerations

-

-

Suture line dehiscence was determined by means of a digital anal examination and by observing postoperative anal discharges.

This usually occurs during the early postoperative phase, including retraction and loss of the tissue. The suture of the internal muscle then loosens, with a consequent overflow of intestinal contents (air, mucus; in severe cases, liquid stools). In most cases, there was an early suture failure that were observed between the fifth and ninth postoperative day or sometimes after defecation.

-

We differentiated between a recurrent and a persistent fistula, depending on whether there was postoperative suture line dehiscence.

-

A recurrent fistula was present when no postoperative suture dehiscence was discovered and a new fistula formed in the scar tissue after complete healing of the wound.

Surgical techniques and perioperative management

Patients without a diverting stoma underwent bowel preparation with oral intestinal lavage (X-prep) 1 day before the operation. All patients received metronidazole and gentamycin or cephalosporins intraoperatively and perioperatively for 3–7 days (mean, 4.2). All procedures were elective and included the anocutaneous flap technique, direct closure, and rectal advancement flap in the prone jackknife position. Either epidural or general anesthesia was performed.

None of the patients received Remicaide or Imurek before, during, or directly after surgery.

In our endo-anal surgical procedures, the fundamental operative technique employed was as follows: The internal opening and the intersphincteric and transsphincteric parts of the fistula are excised very carefully but completely from the fibrotic scarring with a fine scissors, followed by curettage of the intersphincteric plane.

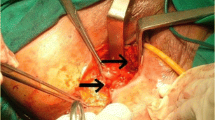

The anal canal was examined with a Parks speculum. The second step comprised preparation and excision of the vaginal fistula ostium and the rest of the fistula tract. In the direct closure group, we closed the excised internal fistula ostium directly using several interrupted sutures (Ethicon PDS® or Ethicon Vicryl® 2.0, Johnson and Johnson Company, Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, 45242-2839, USA). If possible, the first row of sutures connected one external sphincter to the other external sphincter (the index finger was used to press the posterior vaginal wall against it), then a second row connected one internal sphincter to the other internal sphincter, and a third row of sutures connected parts of the internal fibers, the submucosa and the mucosa. This is a direct multilayer closure technique.

Then, depending on the regional conditions, we adapted the rows of sutures either vertically or horizontally, so as to construct a clearly defined and palpatorically stable connection of the external and internal sphincters and the mucosa. Primary closure was also generally applied to the vaginal wound and the rectovaginal septum. It was left open for drainage and healing by secondary intention only in a few cases.

A full thickness rectal flap consisting of mucosa, submucosa, and circular musculature was mobilized semicircumferentially from the level of the intra-anal fistula opening into the perirectal fat about 5 cm cranially so that, after attaining hemostasis, a tension-free closure with the internal sphincter was possible. In the mucosal advancement flap technique, the level of the dissection was in the submucosal area. Mobilization of a 2.5- to 3.0-cm anocutaneous flap in the form of a reversed U entailed sharply separating it from the internal sphincter beginning at the intra-anal fistula opening. A two-layer closure of the sphincters was performed with single sutures, and the anocutaneous flap was loosely fixed to the internal sphincter several millimeters above the level of the internal ostium with separate transanal stitches.

A transperineal fistulectomy is done using a transverse perineal incision about 4–5 cm in length through the perineum above the external sphincter. Dissection between the anterior rectal wall and posterior vaginal wall is performed laterally around the fistula and continued proximally to several centimeters above the fistula tract. The guiding structure we used was the transanally introduced index finger, which simplified complete excision of the fistula tract.

Then, a lateral dissection of the perineal body was carried out, as well as a blunt exposure of the puborectal muscle on both sides. The level of dissection in the rectovaginal septum was high above the fistula opening cranially and laterally so that a tension-free closure was possible. The excised fistula tract was closed in two to three layers using resorbable suture material with several interrupted sutures, either oblique or longitudinally (Vicryl or PDS 2/0). If necessary, the internal opening can also be closed transanally by absorbable interrupted sutures through the mucosa and internal sphincter.

Then, the puborectal muscle was fixed approximately in the midline with 2/0 delayed absorption sutures. In three cases in which a fistula was combined with sphincter destruction and stool incontinence, we performed an anterior anal repair. In two instances, we implemented a U-shaped approximation of the external sphincter and the perineal musculature. In one case, we converted the fistula into a fourth degree perineal tear, followed by a multilayer reconstruction of the anal canal and the perineum. All three reconstructive procedures were applied under the protection of an ileostomy. The transverse perineal muscles and subcutaneous tissue of the perineal body are drawn together with interrupted absorbable sutures (Vicryl 3/0). In most cases, the perineal wound and the skin are closed primarily. The vaginal mucosa and subvaginal fascia were closed longitudinally. A compressive dressing was placed intravaginally to reduce the risk of postoperative bleeding.

Statistical analysis

All manometric data were recorded prospectively on fistula documentation sheets. The group data were compared and the mean preoperative and postoperative pressure values were evaluated using the two-tailed t test or chi-square test. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness-of-fit test and the Shapiro–Wilk test were used to decide whether the empirical distributions of the pressure parameters follow the expected normal distribution. The cutoff for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical computations were performed with SPSS® 10.1 software, version 13 (in German) (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics (condition of the rectum and the sphincters)

At the time of the operation, the rectum was free of signs of inflammation in 26 patients (70%). The other patients had concomitant inflammations of different degrees (minimal rectal disease, eight patients; active rectal disease, three patients).

Thirty patients were fully continent (81%). The other seven patients (19%) had disturbances such as soiling, incontinence for gas and liquid stools, or had to use pads.

Anatomy of the fistula

All vaginal fistulas open into the lower posterior vaginal wall. The vaginal fistula ostium in the posterior vaginal wall was positioned 0.5–3.5 cm (mean, 1.5 cm) cranially from the vaginal introitus. In 34 patients, the ostium was positioned medially; in three patients, laterally to the posterior vaginal wall. The intra-anal fistula ostium was positioned directly below the dentate line in 29 patients. In three patients, it was directly at the dentate line. In five cases, the ostium was directly above the dentate line. A second intravaginal fistula ostium was found in five cases and a second intra-anal fistula ostium in four cases. Thirty-two fistulas were transsphincteric; five were suprasphincteric.

Postoperative complications

In 37 patients, a total of 56 operations was performed in 25 patients (68%), one surgical operation was carried out; 8 patients (21%) had two operations; 2 patients (5.5%) had three operations; 1 patient (2.7%) underwent four fistula operations; and in one patient, five surgical interventions were carried out (Table 1). The time interval between interventions was 7 days–11 months, averaging 5 months. The primary success rate in 19:37 patients was 51%; the definitive success rate was 73% in 27:37 patients. The average number of operations carried out per patient was 1.5. Twelve of the patients (32%) needed more than one operation. The duration of the patients’ stay in hospital was 10.3 days. Muscular suture line dehiscence was the most frequent complication during the postoperative period. It occurred nine times (16%) and was generally found between the fifth and ninth day after surgery. The fistula persisted in all of these patients and, unfortunately, failed to close spontaneously in any case. Recurrent fistulas occurred in eight cases (14%), four within the first three postoperative months, and in 4 cases, after definitive wound healing had already taken place, between the 28th and 42nd postoperative months.

Outcome of methods and comparison of recovery rates

Overall morbidity and the so-called failure rate in the individual techniques vary between 14 and 71% (Table 1). In the advancement flap technique, the failure rate is two to three times higher than with the other techniques. It follows from this that the definitive recovery rates in the long-term follow-ups vary greatly between 29 and 86%; whereby, the advancement flap technique shows the poorest long-term results. The recovery rates were significantly higher with the direct closure and anocutaneous flap technique than with the advancement flap technique (Table 1).

Continence and manometric data

A total of 32 patients (44 procedures) was thoroughly examined preoperatively and postoperatively using anorectal manometry (Table 2). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness-of-fit test and the Shapiro–Wilk test were performed to decide whether the empirical distributions of the pressure parameters conform with the expected normal distribution. Each pressure variable tested is consistent with a normal distribution so that a parametric test (two-tailed t test) can be applied. In the transperineal and advancement flap groups, we found significant changes in the resting pressures: 13% in the transperineal repair group (p < 0.05) and 29% in the advancement flap group (p < 0.001). Similarly, the squeezing pressure was significantly altered with a drop-off of 17% (p < 0.05) in the advancement group. Nonsignificant changes were found in the direct closure and the anocutaneous advancement flap groups. The manometric data obtained with various procedures are shown in Table 2. The mean pressure values for the three patients who had an anterior anal repair increased after the operation: resting pressure from ø 46 preoperatively to ø 80 cmH20, squeezing pressure from ø 74 preoperatively to ø 132 cmH20. The patients filled out questionnaires with respect to their continence. After a follow-up period of 4.5 years, 21 of the 23 patients who had an ileostomy closure were once again fully continent (continence score, 0). In two cases, a loss of continence was reported in the advancement flap group (continence score, 7.5). The advancement flap repair procedure results in about 33% deterioration of the fecal continence (one patient still has a stoma). None of the patients complained of incontinence for solid stools.

Long-term results

In a follow-up period of 10 months to 18 years (mean, 7.1 years), 23 patients had an ileostomy closure, and 3 patients still have a stoma (Table 3). One patient had an ileostomy done in another clinic. Colectomies were performed in eight patients. In the meantime, ano-proctectomies have been performed on five patients with recurrent or persisting fistulas. One patient who had undergone four operations developed a squamons cell carcinoma (histology: pT3, pN0) in a recurrent fistula 42 months after the last operation, and we carried out an ano-procto-colectomy. This patient is free of recurrence after a 4-year follow-up.

In the proctectomy group, one patient developed sepsis after colonic perforation and died 9 months after the operation. Fistulas persist in five other patients. All told, in the long-term follow-up in 37 surgically treated patients, there were ten treatment failures: The success rate was 73%.

Discussion

In our patients with a long follow-up period (up to 18 years), only 51% of the cases were selected for a fistula treatment. A proctectomy was performed a priori in 19%, and there was absolutely no chance of carrying out definitive fistula surgery. The proctectomy rate in the rectovaginal fistula group is reported in the literature to be between 6 and 53% [12, 34–37].

To preserve sphincter muscle integrity and by analogy to the operative treatment of crypto-glandular fistulas, continence-preserving surgical closure techniques have been used more often in the last 25 years for Crohn fistulas as well. In principle, this is a well-established surgical technique that has undergone several modifications over the years. When treating rectovaginal as well as transsphincteric fistulas in Crohn’s disease, the results are generally not as good as those attained when treating crypto-glandular fistulas. In the recent literature, primary recovery rates after transanal advancement flap repair for rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease range from 42 to 100% (mean, 55%), and global recovery rates ranging from 67 to 100% (mean, 70%) have been reported. However, the high recurrence rates of 25–72% (mean, 45%), which show these techniques in a less promising light (Table 4), should be borne in mind.

It is not only anatomical conditions (i.e., supra-anal stenosis, anal canal rigidity, inflammatory process in the rectum, incontinence) that have led us to our differential therapeutic considerations and use of techniques with differing degrees of endoanal mobilization. In an ongoing effort to optimize our surgical techniques, we have implemented and critically evaluated various endoanal closure techniques over the last few years [28–30, 38]. The practical consequences at our clinic have included lower mobilization rates (anocutaneous flap) and multilayer suturing (direct closure). In surgical treatment of transsphincteric anal fistulas, the multilayer direct closure technique has become the therapy of choice [31, 32].

Suture line dehiscence represents the main complication in the postoperative phase for all the techniques presented in this paper. The prevalence of this complication was the most frequent reason for a second surgical session, with 13% in the direct closure group (lowest) and the highest rate in the advancement flap group at 43%.

This “recurrence” results from a tendency of the mobilized flap and/or a local infection to retract as the result of a poor blood supply, leading to suture line dehiscence. A persistent fistula develops as a consequence.

In our opinion, these high recurrence rates are a result of the surgical technique and not solely of the primary diseases. Incision and mobilization in the endoanal area, including the internal sphincter muscle or rectal wall, may be responsible for fibrosis, possibly resulting in an anal deformity that may be associated with soiling. This is also a reason why the advancement flap technique has not become established and why the results are not satisfactory in all the techniques presented in this paper. It is also a reason why publications advocating more conservative procedures have become more frequent in recent years [39–42].

The anocutaneous flap procedure is simpler and more readily understandable. It is generally less prone to retraction and does not involve a risk of damage to the internal sphincter. In our experience, the anocutaneous flap and the transperineal approach are easier to implement than the advancement flap, and postoperative continence is better, as our results show. Both procedures are suitable for treatment of recurrent fistulas that occur after an advancement flap procedure because they avoid a second endoanal mobilization of the internal sphincter.

A possible option for treating non-healing rectovaginal Crohn fistulas would be a transposition of the gracilis muscle, especially in cases with a wide fistular ostium. Using this technique, definitive healing with subsequent stoma closure was achieved in 77% of 13 operated female patients after several unsuccessful attempts with local closure techniques [44–46]. A larger series will be required before a definite conclusion can be drawn. Assessments of the role of diversion (preoperative or synchronous) and the results obtained with different repairs vary in the literature (Table 4).

Basically, the stoma does not guarantee complete healing of the fistula, although it does indeed facilitate postoperative management by enabling enteral feeding of the patient at an earlier stage, thus, shortening considerably the inpatient stay. A loop ileostomy as sole therapy without a fistulectomy only rarely results in complete healing of the fistula. The fistula persists in most such cases, albeit remaining asymptomatic [47, 48]. Primary disease, selection of patients, conservative methods, and a reliable suturing technique are the primary components influencing the outcome of the operated fistula. For these reasons, surgery on complex Crohn fistulas should be performed in specialized hospitals by highly experienced surgeons.

Immunosuppressive therapy with immunomodulators is a major advance in Crohn’s disease management and has been used to treat complex fistulas. However, it has not been evaluated in placebo-controlled trials in which fistula closure was the primary end point [50–54].

There was a positive clinical response in 75 to 90% of patients with perianal fistulas and 50% of patients with rectovaginal fistulas [52, 55]. Small or uncontrolled trials reported a complete closure between 18 to 33% of perianal fistulas and 25% of rectovaginal fistulas. The median response time was 3 months [50, 51, 54]. However, fistula recurrence rates have been shown to be high after treatment was stopped [55]. In contrast to immunosuppressive therapy, infliximab has been proven to be effective in placebo-controlled trials in patients with fistulating Crohn’s disease, and a favorable therapeutic response has been reported in 60 or 70% of the patients after three infusions [56, 57].

Although the initial response to infliximab is very good, the median duration of fistula closure is approximately 3 months so that a regular application of Infliximab is necessary [56, 58].

In the ACCENT II trial, a complete fistula closure was observed in 36% of the patients at week 54 after three infusions compared to 19% of the patients in the placebo cohort [57].

In the long-term treatment of rectovaginal fistula, the duration of fistula closure was longer in the infliximab group (median, 46 weeks) than in the placebo group (33 weeks) [59].

In the reports and ACCENT II trials, the primary end point was a 50% reduction in the discharge of fistulas, and the definition of fistula closure was “no longer drained despite gentle finger compression,” a very general and enlightened definition [56, 57].

Endosonographic and radiological imaging studies after infliximab therapy showed long-term recovery rates for only 14 to 18% for anal fistulas [60–62]. With help of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), it could be demonstrated that despite closure of external orifices after infliximab therapy, fistula tracts persist with varying degrees of residual inflammation, which may cause recurrent fistulas and abscesses [63].

Vaginal or perineal fistulas have a poor prognosis and did not respond clinically to ifliximab therapy [60, 64].

Infliximab therapy in combination with a placement of a seton drainage under anesthesia showed a better initial response [65], but the long-term fistula recovery rates are low (12.5–18%) [58, 64], with a relatively high protectomy rate of 23% [66]. These studies indicate that the clinical and the radiological fistula remission after infliximab treatment differs, and the response rate between perianal and rectovaginal fistulas is also different.

Infliximab is not a substitute for fistula surgery. All four techniques covered in this study are “continence-preserving techniques” that affect continence to varying degrees, as demonstrated by our manometric results. The postoperative manometric deficit is greatest after the advancement flap technique (29%), followed by the transperineal procedure (13%). After direct closure or application of the anocutaneous flap technique, resting pressure does not change significantly in the postoperative phase. Continence changes were only observed after transanal advancement repair that is, of course, also influenced by the internal sphincterotomy in 33% of the patients. Even if the individual techniques are only comparable to a very limited extent, we consider that the manometric results support the use of less aggressive techniques such as the anocutaneous flap and the direct closure technique, as these provide the most effective protection of the anorectal anatomy and of the continence function.

In summary, we conclude that techniques with different preparatory approaches can contribute to effective fistular surgery. The more aggressive the technique used, the greater the detrimental effects on anal sphincter function will be. The technique should be carefully chosen depending on the anorectal morphology. In the majority of cases, it is possible to achieve an endoanal closure with less aggressive treatment modalities. The procedures discussed in this paper vary widely with respect to the risk of recurrence and overall success rate, as well as postoperative manometric resting pressure deficits. Postoperative suture line dehiscence is the main factor leading to recurrence. During a follow-up period of 7.1 years, we were able to demonstrate definitive healing in 27 patients (73%), with a proctectomy rate of 13.5%.

In our experience, the direct closure technique and the anocutaneous flap are the easiest and least drastic procedures. We are absolutely convinced that these techniques enable complete maintenance of the anorectal anatomy and provide superior continence protection. The authors prefer to apply the direct multilayer closure technique without flap.

References

Radcliffe AG, Ritchi JK, Hawley PR, Lennard-Jones JE, Northover JMA (1988) Anovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 31:94–99

Alexander-Williams J (1976) Fistula-in-ano. Management of Crohn’s fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 19:518–519

Buchmann P, Keighley MRB, Allan RN, Thompson H, Alexander-Williams J (1980) Natural history of perianal Crohn’s disease. Am J Surg 140:642–644

Heyen F, Winslet MC, Andrews H, Alexander-Williams J, Keighley MRB (1989) Vaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 32:379–383

Jones IT, Fazio VW, Jagelmann DG (1987) The use of transanal rectal advancement flaps in the management of fistulas involving the anorectum. Dis Colon Rectum 30:919–923

Williams JG, Rothenberger DA, Nemer FD et al (1991) Fistula-in-ano in Crohn’s disease: Results of aggressive surgical treatment. Dis Colon Rectum 34:378–384

Windsor ACJ, Lunniss PJ, Khan UA, Rumbles S, Williams K, Northover JMA (2000) Rectovaginal fistulae in Crohn’s disease: a management paradox. Int J Colorectal Dis 2:154–158

Bandy LC, Addison A, Parker RT (1983) Surgical management of rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol 147:359–363

Sher ME, Bauer JJ, Gelernt I (1991) Surgical repair of rectovaginal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease: transvaginal approach. Dis Colon Rectum 34:641–648

Hesterberg R, Schmidt WU, Muller F, Roeher HD (19993) Treatment of anovaginal fistulas with an anocutaneous flap in patients with Crohn’s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis 8:51–54

Hull TL, Fazio VW (1997) Surgical approaches to low anovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Am J Surg 173:95–98

Penninckx F, Moneghini D, D’Hoore A, Wyndaele J, Coremans G, Rutgeerts P (2001) Surgical repair of rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease: analysis of prognostic factors. Int J Colorectal Dis 3:36–41

Mizrahi N, Wexner SD, Zmora O, Da Silva G, Efron J, Weiss EG, Vernava AM III, Nogueras JJ (2002) Endorectal advancement flap: are there predictors of failure? Dis Colon Rectum 45:1616–1621

Sonoda T, Hull T, Piedmonte MR, Fazio VW (2002) Outcomes of primary repair of anorectal and rectovaginal fistulas using the endorectal advancement flap. Dis Colon Rectum 45:1622–1628

Rothenberger DA, Christenson CE, Balcos EG et al (1982) Endorectal advancement flap for treatment of simple rectovaginal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 25:297–300

Oh C (1983) Management of high recurrent anal fistula. Surgery 93:330–332

Wise WE Jr, Aguilar PS, Padmanabhan A, Meesing DM, Arnold MW, Stewart WR (1991) Surgical treatment of low rectovaginal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 34:271–274

Hyman N (1999) Endoanal advancement flap repair for complex anorectal fistulas. Am J Surg 178:337–340

Bartolo DCC, Lewis P (1990) Treatment of transsphincteric fistulae by full thickness anorectal advancement flaps. Br J Surg 77:1187–1189

Bermann IR (1991) Sleeve advancement anorectoplasty for complicated anorectal/vaginal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 34:1032

Aguilar PS, Plasencia G, Hardy TG Jr, Hartmann RF, Steward WRC (1985) Mucosal advancement in the treatment of anal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 28:496–498

Kodner IJ, Mazor A, Shemesh EI, Fry RD, Fleshmen JW, Birnbaum EH (1993) Endorectal advancement flap repair of recto-vaginal and other complicated anorectal fistulas. Surgery 114:682–690

Ozuner G, Hull TL, Cartmill J, Fazio VW (1996) Long-term analysis of the use of transanal rectal advancement flaps for complicated anorectal/vaginal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 39:10–14

Joo JS, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD (1998) Endorectal advancement flap in perianal Crohn’s disease. Am Surg 64:147–150

Makowiec F, Jehle EC, Becker HD, Starlinger M (1995) Clinical course after transanal advancement flap repair of perianal fistula in patients with Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg 82:603–606

Schouten WR, Zimmermann DDE, Briel JW (1999) Transanal advancement flap repair of transsphincteric fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 42:1419–1423

Zimmerman DDE, Briel JW, Gosselink MP, Schouten WR (2001) Anocutaneous advancement flap repair of transsphincteric fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 44:1474–1480

Athanasiadis S, Köhler A, Nafe M (1994) Treatment of high anal fistulas by primary occlusion of the internal ostium and mucosal advancement flap. Clinical and functional long-term results in 224 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 9:153–157

Athanasiadis S, Köhler A, Weyand G, Nafe M, Kuprian A, Oladeinde I (1996) Endoanal and transperineal sphincter-saving techniques in the surgical treatment of Crohn fistulas. A prospective long term study in 186 patients. Chirurg 67:59–71, (in German)

Athanasiadis S, Oladeinde I, Kuprian A, Keller B (1995) Endorectal advancement flap vs. transperineal repair in the treatment of rectovaginal fistulae. Chirurg 66:493–502 (in German)

Athanasiadis S, Helmes C, Yazigi R, Köhler A (2004) The direct closure of the internal fistula opening without advancement flap for transsphincteric fistulas-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 47:1174–1180

Köhler A, Risse-Schaaf A, Athanasiadis S (2004) Treatment for horseshoe fistulas-in-ano with primary closure of the internal fistula opening. A clinical and manometric study. Dis Colon Rectum 47:1874–1882

Jorge JMN, Wexner SD (1993) Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 36:77–97

Scott NA, Nair A, Hughes LE (1992) Anovaginal and rectovaginal fistula in patients with Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg 79:1379–1380

Morrison JG, Gathrigth JB Jr, Ray JE, Ferrari BT, Hicks TC, Timmcke AE (1989) Results of operation for rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 32:497–499

Wiskind AK, Thompson JD (1992) Transverse transperineal repair of rectovaginal fistulas in the lower vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol 167:694–699

Michelassi F, Melis M, Rubin M, Hurst RD (2000) Surgical treatment of anorectal complications in Crohn’s disease. Surgery 128:597–603

Athanasiadis S, Nafe M, Köhler A (1995) Transanal rectal advancement flap vs. mucosal flap with suture of the internal sphincter muscle for the management of complicated anorectal fistulas. A prospective clinical and manometric study. Langenbecks Arch Chir 380:31–36 (in German)

Del Pino A, Nelson RL, Pearl RK, Abcarian H (1996) Island flap anoplasty for treatment of transsphincteric fistula in ano. Dis Colon Rectum 39:224–226

Van Tets WF, Kuijpers JH (1995) Seton treatment of perianal fistula with high anal or rectal opening. Br J Surg 82:895–897

Cintron J, Park J, Orsay CP, Pearl RK, Nelson RL, Abcarian H (1999) Repair of fistulas-in-ano with autologous fibrin tissue adhesive. Dis Colon Rectum 42:607–613

O’Connor L, Champagne BJ, Fergueson MA, Orangio GR, Schertzer ME, Armstrong DN (2006) Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of Crohn’s anorectal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 49:1569–1573

Champagne BJ, O’Connor L, Fergueson MA, Orangio GR, Schertzer ME, Armstrong DN (2006) Efficacy of anal fistula plug in closure of cryptoglandular fistulas: long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum 49:1817–1821

MacRae HM, McLeod RS, Cohen Z et al (1995) Treatment of rectovaginal fistulas that has failed previous repair attempts. Dis Colon Rectum 38:921–925

Hum M, Solh W, Baig MK et al (2004) The use of gracilis muscle transposition in anorectal fistula (abstracts). Dis Colon Rectum 47:610

Zmora O, Tulchinsky H, Gur E, Goldman G, Klausner JM, Rabau M (2006) Gracilis muscle transposition for fistulas between the rectum and urethra or vagina. Dis Colon Rectum 49:1316–1321

Harper PH, Kettlewell MGW, Lee ECG (1982) The effect of split ileostomy on perianal Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg 69:608–610

Grant DR, Cohen Z, McLeod RS (1986) Loop ileostomy for anorectal Crohn’s disease. Can J Surg 29:32–35

Yamamoto T, Allan RN, Keighley MRB (2000) Effect of Fecal Diversion Alone on perianal Crohn’s disease. World J Surg 24:1258–1263

Present DH, Korelitz BI, Wisch N, Glass JL, Sachar DB, Pasternack BS (1980) Treatment of Crohn’s disease with 6-mercaptopurine. A long-term, randomized, double-blind study. N Engl J Med 302:981–987

Korelitz BI, Present DH (1985) Favorable effect of 6-mercaptopurine on fistulae of Crohn’s Disease. Dig Dis Sci 30:58–64

O’Brien JJ, Bayless TM, Bayless JA (1991) Use of azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine in the treatment of Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 101:39–46

O’Neill J, Pathmakanthan S, Goh J (1997) Cyclosporine A induces remission in fistulous Crohn’s disease but relapse occurs upon cessation of treatment. Gastroenterology 112:A1056

Present DH, Lichtiger S (1994) Efficacy of cyclosporine in treatment of fistula of Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci 39(2):374–380

Dejaco C, Harrer M, Waldhoer T, Miehsler W, Vogelsang H, Reinisch W (2003) Antibiotics and azathioprine for the treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 18(11–12):1113–1120

Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S et al (1999) Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s Disease. N Engl J Med 340:1398–1405

Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN et al (2004) Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 350:876–885

Regueiro M, Mardini H (2003) Treatment of perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease with infliximab alone or as adjunct to exam under anesthesia with seton placement. Inflamm Bowel Dis 9:98–103

Sands BE, Blank MA, Patel K, van Deventer SJ (2004) Long-term treatment of rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: response to infliximab in the ACCENT II study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2(10):912–920

van Bodegraven AA, Sloots CEJ, Felt-Bersma RJF et al (2002) Endosonographic evidence of persistence of Crohn’s disease associated fistulas after infliximab treatment, irrespective of clinical response. Dis Colon Rectum 45:39–46

Rasul I, Wilson SR, MacRae H, Irwin S, Greenberg GR (2004) Clinical and radiological responses after infliximab treatment for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 99(1):82

Ardizzone S, Maconi G, Colombo E, Manzionna G, Bollani S, Bianchi Porro G (2004) Perianal fistulae following infliximab treatment: clinical and endosonographic outcome. Inflamm Bowel Dis 10(2):91–96

Van Assche G, Vanbeckevoort D, Bielen D et al (1998) Magnetic resonance imaging of the effects of infliximab on perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 332–339

Topstad DR, Panaccione R, Heine JA et al (2003) Combined seton placement, infliximab infusion, and maintenance immunosuppressives improve healing rate in fistulizing anorectal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 46:577–583

Talbot C, Sagar PM, Johnston MH, Finan PJ, Burke D (2005) Infliximab in the surgical management of complex fistulating anal Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis 7:164–168

Hyder SA, Travis SPL, Jewell DP et al (2006) Fistulating anal Crohn’s disease: results of combined surgical and infliximab treatment. Dis Colon Rectum 49:1837–1841

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Athanasiadis, S., Yazigi, R., Köhler, A. et al. Recovery rates and functional results after repair for rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease: a comparison of different techniques. Int J Colorectal Dis 22, 1051–1060 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-007-0294-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-007-0294-y