Abstract

We evaluated the outcome in infants with esophageal atresia (EA) treated in our department over the last two decades. The medical records of 147 infants treated from 1986 to 2005 were reviewed. Patient characteristics, associated anomalies, surgery and complications were recorded. We divided the material into two time-periods: 1986–1995 and 1996–2005; 125 patients or parents were interviewed regarding gastrointestinal function, respiratory symptoms and education. The incidence of major cardiac defects increased from 23 to 29% and the overall survival increased from 87 to 94%. Using Spitz’ classification survival increased from 93.5 to 100% in group I and from 68.4 to 77.8% in group II. In group III, during the second time period, survival was 100% in three patients. The incidence of anastomotic leakage and recurrent fistula did not change over time. The rate of anastomotic strictures increased from 53 to 59% between the two time-periods. A primary anastomosis could be done in 85% of the patients during the second period versus 78% of the patients during the first period. Anti-reflux surgery was done in only 11 and 9%, respectively, during the two time-periods. In patients who were 16–20 years old, 40–50% had gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms. Ninety percent of the patients attended normal school. The major difference between the periods 1986–1995 and 1996–2005 was an increased survival despite an increased incidence of major cardiac defects. Gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms were frequent. Long-term follow-up and treatment of complications of esophageal atresia is important for this patient group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

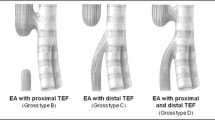

Esophageal atresia (EA) is a malformation occurring in 1:2,500 births [1]. The outcome of neonates with EA has dramatically improved since Haight and Towsley [2] reported the first successful primary repair in 1943. Even though advances in neonatal, pediatric surgical and cardiac care have improved the overall survival rate in infants with EA [3–8] gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms are reported in long-term follow-up studies and may interfere with normal life [9–12].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the outcome and late sequelae in patients with EA treated in our institution over the last two decades. We also wanted to evaluate if Spitz’ classification is useful in our setting.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all the 147 infants that were operated for EA 1986–2005 at the Department of Pediatric Surgery in Uppsala. During this time period there were nine patients that were not operated. Four of these had trisomy 18, four of the patients had severe cardiac malformations and one patient had bilateral renal agenesia. Data were obtained on birth weight, sex, gestational age, age and parity of the mother, polyhydramnios, type of atresia, presence of cardiac defects, chromosomal abnormalities and other anomalies, age at surgery, type of operation, postoperative complications, duration of primary hospital stay, survival and cause of death. A major cardiac anomaly was defined as a congenital heart disease that required medical or surgical treatment. We excluded patent ductus arteriosus unless it required surgical ligation. A diagnosis of VACTERL (vertebra, anorectal, cardiac, tracheo-esophageal, radial/renal, limb) association was made if three or more components of the association were present. An anastomotic stricture was recorded when at least one dilatation was required. To compare changes over time, the patients were divided in two groups: 1986–1995 and 1996–2005. There were no major differences between the two time-periods, regarding how patients with EA were managed. We obtained the addresses of 132 survivors from the Swedish Population Register Center. The parents of these patients received a letter, in which they were asked to at a later occasion participate in a telephone interview regarding their child’s food habits, dysphagia, gastroesophageal reflux (GER) symptoms, respiratory tract symptoms, medication, physical activity and education. In patients younger than 15 years of age, the parents were interviewed. Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test or Chi-squared test with Yates’ continuity correction. Local ethical approval for the study was obtained.

Results

The distribution of anatomical variants was similar in the two groups (Table 1). There was a decrease in the total number of patients treated during the last 10 years. The decrease was seen in the treated number of boys 1996–2005 (Table 2). The mean age of the mother, mean gestation age and mean birth weight did not change significantly over the two time-periods (Table 2). The percentage of EA without any other malformations, chromosomal abnormalities and VACTERL association remained stable during the two time-periods (Table 2). In contrast, the numbers of major cardiac defects and patients with very low birth weight (<1,500 g) were larger during 1996–2005 (Table 2). The mortality rate has fallen in the last 10 years (Table 2). In the 11 deaths 1986–1995, eight were caused by major cardiac defects, one by anastomotic leakage, abscess and sepsis in a patient with long gap EA, and two deaths occurred in patients with trisomy 18. All four deaths in the patients operated 1996–2005 were caused by major cardiac defects and one of these also had trisomy 18. We have not operated infants with EA and trisomi 18 after 2000 as surgery is of no benefit in such a lethal congenital anomaly.

Table 3 compares the survival during the two time-periods based on birth weight and presence of a major cardiac anomaly according to the Spitz’ classification. There was an improvement in survival for group I and II infants; however, it was not statistically significant. Although the survival in group III patients has increased from 0 to 100%, the small number of infants prevented the results from being statistically significant. There was no mortality in group II infants without a major cardiac anomaly in the period 1996–2005. Polyhydramnios was recorded in 20 (24%) cases in the first and in 17 (26%) cases during the second time period. The mean duration of primary hospital stay was 24 days in the early time period and 20 days in the later. In both groups the majority of patients were operated within 24–48 h after birth.

A gastrostomy was performed in 15% of the patients in the early period versus 6% in the later period and a primary anastomosis was fashioned more frequently (Table 4). The 12 patients with gastrostomy in the early period consisted of eight patients with long-gap EA. Three patients in the early group had major cardiac defects and were at the time of surgery not stable enough to be treated with a primary anastomosis, instead they had a ligation of a distal esophageal fistula and a gastrostomy. One patient in the early period had a gastrostomy after the repair of a primary major anastomotic leak. In the later time period four patients were treated with gastrostomy (Table 4), three patients had pure EA. One patient had a gastrostomy and ligation of a distal esophageal fistula because of very low birth weight (525 g); consequently, the esophagus ends were too fragile to perform a primary anastomosis. In the period from 1986 to 1995, three patients were treated with colon interposition (Table 4). The youngest patient was 13 months and the oldest 20 months. One gastric transposition was performed at the age of 19 months in the early time period (Table 4). No patient was treated with cervical esophagostomy in the last 10 years. No esophageal replacement was performed during 1996–2005. Two patients with long gap EA were treated with delayed primary anastomosis, one patient at the age of 5 months and the other at the age of 7 months. The third patient with long gap EA and the very low birth weight patient were both operated with a mobilization of the stomach and a primary anastomosis at the age of 5 and 8 months, respectively. Infants with an isolated tracheoesophageal fistula were treated with a fistula ligation.

Table 5 shows the complications in the two time-periods. The incidence of anastomotic leak did not change over time. In contrast there was an increase in the percentage of strictures. The strictures were all treated by balloon dilatation and the mean number of dilatations performed was four (range 1–30). Recurrent tracheoesophageal fistula occurred in 10% of the patients in the early and in 5% of the infants in the later time period. The number of fundoplications performed was low in both groups.

We performed telephone interviews with 125 patients with EA, or their parents, operated during the last two decades (1986–2005). Table 6 demonstrates the different groups of age at the time of interview. The median age at the interview was 10 years.

Incidence of dysphagia, GER symptoms, frequent coughing, a period of more than three respiratory infections requiring antibiotics, shortness of breath, impaired exercise capacity and medications is shown in Table 7. The incidence of dysphagia remained stable around 60% in all the different age groups and the incidence of GER symptoms were present in approximately 40% in all age groups. Only 6% of the patients in the age group 16–20 years had anti-reflux medication. In the age group 16–20 years, 36% of the patients reported frequent coughing and 20% considered that they had impaired exercise capacity. The incidence of respiratory infections and shortness of breath increased in the older age groups. The percentage of patients with asthma medication was the same in the youngest and oldest age group. Problems with food getting stuck decreased by time. Among the 88 patients in the school age, the majority (90%) could attend a normal school. In the age group 16–20 years, 21 attended high school, four attended university, three were working and two were unemployed.

Discussion

Despite an increased incidence of major cardiac defects in infants with EA treated over the last 10 years in our pediatric surgical center, the survival rate has increased as earlier reported by others [4–7]. The incidence of chromosomal abnormalities and VACTERL association remained similar and unchanged over time in our study as reported by Tönz et al. [4], but in contrast to our findings they did not show any increase in the presence of major cardiac anomalies. Other patient characteristics such as sex ratio, birth weight, gestational age and type of atresia are comparable with other reports [4, 5, 13–15].

Several risk factors have previously been identified for the outcome in patients with EA. The Waterstone classification from 1962 includes risk factors as low birth weight, preoperative pneumonia and associated congenital anomalies [16]. Montreal used the need for preoperative ventilation as a predictor for outcome but included not the birth weight as a risk factor [17]. With advances in neonatal intensive care and pediatric anesthesia, the relevance of these classification systems have been questioned [3, 18]. However, in developing countries the Waterstone classification still seems valid [19]. In 1994 Spitz et al. [18] identified the two main factors of survival prognosis for infants with EA; birth weight and major cardiac malformations. The fact that the majority of deaths in the different time periods in our study were caused by major cardiac defects makes the Spitz classification the most relevant predictor of survival in our patients. When using the Spitz classification system, we found an increased survival rate for group I and II infants comparing the two time-periods. In addition, we had no mortality in group II infants without a major cardiac anomaly in the second time period. The presence of a major cardiac anomaly seems to be a stronger predictor of survival than prematurity in our patients. This indirectly indicates an improvement in the neonatal care including nutritional and ventilatory support. When comparing our results with those reported by Lopez et al. [3], we found a slightly higher mortality in our group II infants the last decade, 77.8 versus 82%. Even if there are only three infants in group III the last time period, we are satisfied to show a 100% survival. Lopez et al. had six patients in group III the last decade and the survival was 50%. Also Choudhury et al. [8] demonstrated a 50% survival rate in eight group III infants.

The incidence of anastomotic leaks remained stable between 6 and 7% in the two time-periods and was at the same levels as those recent reports by Tönz et al. [4] and Konkin et al. [6]. In contrast, Orford et al. [5] found a higher incidence of anastomotic leak (17%). In our present study all patients, except one, were successfully treated with conservative regimen. We had problems to compare results regarding anastomotic esophageal strictures, as there is not any universal definition in the literature. In the majority of studies, the incidence is between 37 and 52% [1, 4–6]. However, in the review by Kovesi et al. [20] 69% of patients with EA require esophageal sounding or dilatation. Risk factors of strictures are gastroesophageal reflux, anastomotic tension and leakage [1, 21]. As the incidence of anastomotic leak remained unchanged in our patients, the slight increase in anastomotic strictures may mainly be due to higher rate of primary anastomosis with more extensive mobilization of the distal esophagus, thus interfering with the blood supply. In addition, mobilization of the distal esophagus and superior displacement of the esophagastric junction will promote GER [20]. Since 2002 all infants with EA and a primary anastomosis are routinely treated with omeprazole as soon as they can be orally fed. It will be interesting to investigate whether this routine will decrease the stricture formation in the future. Recurrent tracheoesophageal fistula in our patients with EA are in concordance with other reports [1, 6, 20].

In the 1986–1995-period, three patients with a major cardiac defect had gastrostomy as they were considered not stable enough to undergo a primary repair. This was not an indication in the 1996–2005-period, again indicating the progress in neonatal intensive care and pediatric anesthesia the last decade. We have not had any patient requiring esophageal replacement during the last 10 years. Instead, we have succeeded to perform a delayed primary anastomosis. This method is more attractive as it preserves the native esophagus and seems to be the surgical method recommended [1]. In our experience colonic interposition has been associated with a lot of difficulties.

GER is common in patients with EA occurring in 35 to 58% of the patients [1, 10, 21, 22]. GER appears to be due to abnormal esophageal motility [23], dysmotility of the stomach, [24] and with slow gastric emptying [25]. Primary malformations of the nerve supply and intraoperative damage to nerves supplying the esophagus may be other mechanisms resulting in GER [26–28]. The optimal treatment of GER is still a controversy; some investigators recommend early fundoplication, whereas others prefer medical treatment. Fundoplication carries a more than 40% recurrence rate in early infancy [29]. Overall, 13–32% require fundoplication [8, 11, 12, 22]. In our patients, fundoplication was undertaken less frequently than previously reported. We limited fundoplication to the most severe cases with insufficient effect of intensive medical therapy in agreement with the recent trend toward more aggressive medical treatment and less fundoplications [1, 30].

It is well known that the most significant problems in patients with EA are gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms and the incidences vary from 30 to 60% in the literature [12, 22, 31, 32]. The incidence of gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms is thought to decrease by time [9, 11, 12]. In our study, we were surprised to find out that gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms did not improve as the patients became older. In a comparable study by Little et al. [11], including 69 patients, these complications occurred most frequently during the first 5 years in life. The incidence of dysphagia was 48%, GER 31% and respiratory infections 10% in their patients older than 10 years. The corresponding incidences in our patients were all higher (64, 44 and 56%). Koivusalo et al. [9] studied 128 patients with a median age of 38 years. They found respiratory symptoms in 25% and gastrointestinal symptoms in 40% of the patients. Despite a high incidence of GER symptoms in our patients 16–20 years old (43%) only 6% had anti-reflux treatment. This could partly explain why our patients have more gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms than in those previous reports. It is also possible that some of these patients need a fundoplication as it was undertaken less frequently in our patients than in other reports. It also makes us aware that the follow-up of our patients with EA need to be improved whether it will be in our center of pediatric surgery or by the local pediatricians. Additionally, we must improve the transition from pediatric to the adult services and make the adult colleagues aware of the problems of patients born with EA. Many of our older patients interviewed seem to adapt to the symptoms and considered them as normal.

Bouman et al. [33] showed that children with EA have more learning, emotional and behavioral problems than children in the general population. Lindahl et al. [34] reported IQ in the normal range in children with EA. The results are probably dependant on the presence of associated congenital malformation and prematurity. In our study, we did not perform any deeper analysis with physiological tests but found that 90% of our patients could attend normal class.

In conclusion, the Spitz’ classification still seems to be valid. The presence of a major cardiac anomaly seems to be a stronger predictor of survival than prematurity in our patients, indirectly indicating an improvement in the neonatal care. Gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms in these patients were frequent. Long-term follow-up as well as early recognition and treatment of sequelae of esophageal atresia are of outmost importance.

References

Spitz L (2006) Esophageal atresia. Lessons I have learned in a 40-year experience. J Pediatr Surg 41:1635–1640

Haight C, Towsley HA (1943) Congenital atresia of the esophagus with tracheoesophageal fistula. Extrapleural ligation of fistula and end-to-end anastomosis of esophageal segments. Surg Gynecol Obstet 76:672–688

Lopez PJ, Keys C, Pierro A, Drake DP, Kiely EM, Curry JI, Spitz L (2006) Oesophageal atresia: Improved outcome in high-risk groups? J Pediatr Surg 41:331–334

Tonz M, Kohli S, Kaiser G (2004) Oesophageal atresia: what has changed in the last 3 decades? Pediatr Surg Int 20:768–772

Orford J, Cass DT, Glasson MJ (2004) Advances in the treatment of oesophageal atresia over three decades: the 1970s and the 1990s. Pediatr Surg Int 20:402–407

Konkin DE, O’Hali WA, Webber EM, Blair GK (2003) Outcomes in esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. J Pediatr Surg 38:1726–1729

Deurloo JA, Ekkelkamp S, Schoorl M, Heij HA, Aronson DC (2002) Esophageal atresia: historical evolution of management and results in 371 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 73:267–272

Choudhury SR, Ashcraft KW, Sharp RJ, Murphy JP, Snyder CL, Sigalet DL (1999) Survival of patients with esophageal atresia: influence of birth weight, cardiac anomaly, and late respiratory complications. J Pediatr Surg 34:70–73 (discussion 74)

Koivusalo A, Pakarinen MP, Turunen P, Saarikoski H, Lindahl H, Rintala RJ (2005) Health-related quality of life in adult patients with esophageal atresia—a questionnaire study. J Pediatr Surg 40:307–312

Tomaselli V, Volpi ML, Dell’Agnola CA, Bini M, Rossi A, Indriolo A (2003) Long-term evaluation of esophageal function in patients treated at birth for esophageal atresia. Pediatr Surg Int 19:40–43

Little DC, Rescorla FJ, Grosfeld JL, West KW, Scherer LR, Engum SA (2003) Long-term analysis of children with esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. J Pediatr Surg 38:852–856

Somppi E, Tammela O, Ruuska T, Rahnasto J, Laitinen J, Turjanmaa V, Jarnberg J (1998) Outcome of patients operated on for esophageal atresia: 30 years’ experience. J Pediatr Surg 33:1341–1346

Sillen U, Hagberg S, Rubenson A, Werkmaster K (1988) Management of esophageal atresia: review of 16 years’ experience. J Pediatr Surg 23:805–809

Rokitansky AM, Kolankaya VA, Seidl S, Mayr J, Bichler B, Schreiner W, Engels M, Horcher E, Lischka A, Menardi G et al (1993) Recent evaluation of prognostic risk factors in esophageal atresia—a multicenter review of 223 cases. Eur J Pediatr Surg 3:196–201

Louhimo I, Lindahl H (1983) Esophageal atresia: primary results of 500 consecutively treated patients. J Pediatr Surg 18:217–229

Waterston DJ, Carter RE, Aberdeen E (1962) Oesophageal atresia: tracheo-oesophageal fistula. A study of survival in 218 infants. Lancet 1:819–822

Teich S, Barton DP, Ginn-Pease ME, King DR (1997) Prognostic classification for esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula: Waterston versus Montreal. J Pediatr Surg 32:1075–1079 discussion 1079–1080

Spitz L, Kiely EM, Morecroft JA, Drake DP (1994) Oesophageal atresia: at-risk groups for the 1990s. J Pediatr Surg 29:723–725

Sharma AK, Shekhawat NS, Agrawal LD, Chaturvedi V, Kothari SK, Goel D (2000) Esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula: a review of 25 years’ experience. Pediatr Surg Int 16:478–482

Kovesi T, Rubin S (2004) Long-term complications of congenital esophageal atresia and/or tracheoesophageal fistula. Chest 126:915–925

Chittmittrapap S, Spitz L, Kiely EM, Brereton RJ (1990) Anastomotic stricture following repair of esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg 25:508–511

Engum SA, Grosfeld JL, West KW, Rescorla FJ, Scherer LR III (1995) Analysis of morbidity and mortality in 227 cases of esophageal atresia and/or tracheoesophageal fistula over two decades. Arch Surg 130:502–508 (discussion 508–509)

Kirkpatrick JA, Cresson SL, Pilling GP IV (1961) The motor activity of the esophagus in association with esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 86:884–887

Cheng W, Spitz L, Milla P (1997) Surface electrogastrography in children with esophageal atresia. Pediatr Surg Int 12:552–555

Montgomery M, Escobar-Billing R, Hellstrom PM, Karlsson KA, Frenckner B (1998) Impaired gastric emptying in children with repaired esophageal atresia: a controlled study. J Pediatr Surg 33:476–480

Davies MR (1996) Anatomy of the extrinsic motor nerve supply to mobilized segments of the oesophagus disrupted by dissection during repair of oesophageal atresia with distal fistula. Br J Surg 83:1268–1270

Qi BQ, Merei J, Farmer P, Hasthorpe S, Myers NA, Beasley SW, Hutson JM (1997) The vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves in the rodent experimental model of esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg 32:1580–1586

Cheng W, Bishop AE, Spitz L, Polak JM (1999) Abnormal enteric nerve morphology in atretic esophagus of fetal rats with adriamycin-induced esophageal atresia. Pediatr Surg Int 15:8–10

Kubiak R, Spitz L, Kiely EM, Drake D, Pierro A (1999) Effectiveness of fundoplication in early infancy. J Pediatr Surg 34:295–299

Holcomb GW III, Rothenberg SS, Bax KM, Martinez-Ferro M, Albanese CT, Ostlie DJ, van Der Zee DC, Yeung CK (2005) Thoracoscopic repair of esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula: a multi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg 242:422–428 (discussion 428–430)

Ure BM, Slany E, Eypasch EP, Weiler K, Troidl H, Holschneider AM (1998) Quality of life more than 20 years after repair of esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg 33:511–515

Agrawal L, Beardsmore CS, MacFadyen UM (1999) Respiratory function in childhood following repair of oesophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. Arch Dis Child 81:404–408

Bouman NH, Koot HM, Hazebroek FW (1999) Long-term physical, psychological, and social functioning of children with esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg 34:399–404

Lindahl H (1984) Long-term prognosis of successfully operated oesophageal atresia-with aspects on physical and psychological development. Z Kinderchir 39:6–10

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lilja, H.E., Wester, T. Outcome in neonates with esophageal atresia treated over the last 20 years. Pediatr Surg Int 24, 531–536 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-008-2122-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-008-2122-z