Abstract

Diurnal (S1) and semidiurnal (S2) oscillations are major factors in determining the sub-daily variations of precipitation amount over Southeast China (PSEC). Most studies have examined the causes of S1(P)SEC and S2(P)SEC in the summer rainy season. However, causes of the seasonal changes in S1(P)SEC and S2(P)SEC have not been well documented. This study therefore examines possible mechanisms behind various precipitation types/cloud types because different types of precipitation/clouds control PSEC in different seasons. Results indicate that the variation of S1(P)SEC in winter, which tends to peak in the early morning, is mainly controlled by the high-relative-humidity-induced diurnal variation of non-showery precipitation/middle-level clouds. For S1(P)SEC in the other seasons, which tends to peak at the late afternoon, the moist-convection-induced diurnal variation of showery precipitation/low-level clouds is the main cause. Analyses also suggest that the phase of S2(P)SEC does not vary seasonally because both of its formation mechanisms—the semidiurnal variation of relative humidity and moist convection process—have similar phase evolution in all seasons. Seasonal changes in the water vapor supply to the maintenance of S1(P)SEC and S2(P)SEC are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It has been widely suggested that the characteristics and formation mechanisms of sub-daily variations of precipitation are location dependent (e.g. Chan and Ng 1993; Chen et al. 1999; Zhao et al. 2005; Yang and Smith 2006; Dai et al. 2007; Yu et al. 2007a, b; Yu et al. 2010; Zhou et al. 2008; Kikuchi and Wang 2008; Chen et al. 2009). For the precipitation over East Asia, it is generally controlled by different precipitation types/cloud types during different seasons (Dai 2001a). Because different types of precipitation/clouds are likely induced by different formation mechanism (Houze 1993), an investigation on the seasonal behavior of various precipitation types/cloud types should provide insights into causes of seasonal changes in the sub-daily variations of precipitation amount (e.g. Dai 2001b; Chen et al. 2010). Such an examination, however, has not yet been applied to explain seasonal changes in the sub-daily variations of precipitation amount over Southeast China [hereafter SEC; an area covering (110°–118°E, 21°–25°N)].

As seen from Fig. 1a, SEC is one of the areas with the largest variability of 3-hourly precipitation amount in East Asia. The temporal variation of precipitation amount over SEC (PSEC) consists of clear diurnal [hereafter, S1(P)SEC] and semidiurnal [S2(P)SEC] signals for all seasons (Fig. 1b) (e.g. Yin et al. 2009). The rainfall variations, which evolve with periods of 24 and 12 h, are often referred to as the diurnal and semi-diurnal oscillations respectively (e.g. Ramage 1952). Li et al. (2008) noted that the summer precipitation over inland regions of China tends to be more frequent in the afternoon; but, during the other seasons, precipitation has a much weaker diurnal cycle than in the summer, with a morning maximum in the winter over SEC. Huang et al. (2010) further indicated that such a seasonal change in PSEC is mainly controlled by its related S1(P)SEC, which varies in response to a seasonal-varying large-scale diurnal atmospheric circulation. Because seasonal transition of predominant precipitation type/cloud type has not been considered in Huang et al. (2010), it is likely that other mechanisms might also be important in the explanation of the seasonal variation of S1(P)SEC.

a Variance of 3-hourly precipitation amount (P) estimated from TRMM-3G68 2B31 data production for the period of 1998–2009. The mountain areas (left of the green dotted line) in a are blocked. b Power spectrum of P area-averaged over Southeast China (SEC; 110–118°E; 21–25°N; solid boxed area in a) for the 1998–2009 winter (December, January and February or DJF), spring (March, April and May or MAM), summer (June, July and August or JJA), and autumn (September, October and November or SON) seasons. The dotted boxed area in a is referred to the selection of domain of South China Sea (SCS) that used for the analysis of Fig. 10

For the variation of S2(P)SEC, which explains about 30% of the total hour-to-hour variability of PSEC in the summer (e.g. Zhou et al. 2008), its formation mechanism has rarely been examined because the temporal resolution of most available global reanalyses is 6-h which might not be appropriate for representing the semidiurnal variation. Based on a newly released 3-hourly GEOS5 (Goddard Earth Observing System Model Version 5; Rienecker et al. 2008) reanalysis dataset, we have recently examined and proposed that the formation of S2(P)SEC in the summer is a result of an atmospheric circulation change induced by the semidiurnal land-sea differential heating between SEC and its nearby oceans (Huang and Chan 2011). An examination on the seasonal behavior of clouds, which are important in the earth’s climate system because of their effects on solar radiation, might help clarify whether or not Huang and Chan’s (2011) proposed mechanism is also true for the causes of S2(P)SEC in the other seasons.

The main objective of this study is therefore to identify possible causes of seasonal variations of S1(P)SEC and S2(P)SEC from a perspective of seasonal changes in predominant precipitation type/cloud type, which is important for a better understanding of regional weather and climate change. The data and methodology used for the analyses are introduced in Sect. 2. Section 3 documents the seasonal behavior of sub-daily variations of precipitation amount and precipitation type over SEC. Mechanisms important for the seasonal variations of S1(P)SEC and S2(P)SEC are discussed in Sects. 4 and 5 respectively, followed by a summary in Sect. 6.

2 Data and meteorology

To resolve diurnal and semidiurnal cycles, a sampling rate of 3-hourly observational data is sufficient (Dai 2001a, b). Therefore, precipitation analysis uses a 3-hourly, 0.5° longitude × 0.5° latitude gridded TRMM (Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission; Simpson et al. 1996) 3G68 2B31 precipitation dataset which uses both passive and active microwave data to produce the best rain estimate for TRMM (Haddad et al. 1997a, b). This production has been shown to resemble rain gauge observations with a good representation of the diurnal rainfall variability (Hong et al. 2005; Kikuchi and Wang 2008). For the examination of atmospheric conditions, meteorological variables (including temperature, relative humidity, wind fields, net radiative heating, etc.) are extracted from the 3-hourly GEOS5 reanalysis dataset (Rienecker et al. 2008) because the GEOS5 data with a spatial resolution of 0.667° longitude × 0.5° latitude can depict the regional feature better than other 6-hourly reanalyses with a coarser resolution (Huang et al. 2010). Our previous works (Huang et al. 2010; Huang and Chan 2011) have shown that GEOS5 reanalysis data are capable of depicting the sub-daily variations of moisture-process-related meteorological variables over the SEC. For data uniformity, all gridded data used in this study have been interpolated onto a 1o longitude × 1o latitude spatial basis by bilinear interpolation. The analysis covers a time period from 1998 to 2009 for the winter (December, January and February, or DJF), spring (March, April and May, or MAM), summer (June, July, August, or JJA) and autumn (September, October and November, or SON) seasons.

Observations of precipitation types are obtained from the Extended Edited Cloud Reports Archive (EECRA; Hahn et al. 1999), which provides 3-hourly weather reports from about 15,000 station and ship observations. In the EECRA reports, synoptic weather codes of major precipitation types including drizzle (code number 50–58), non-showeryFootnote 1 (code number 59–79) and showery (code number 80–99) are defined specifically by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO; WMO 1988). A detailed procedure for generating a global gridded climatology of 3-hourly frequency of occurrence for drizzle, non-showery and showery precipitation from the EECRA reports has been documented in Dai (2001a, b). This global gridded data,Footnote 2 which incorporate data from the EECRA reports for the period of 1975–1997, with a spatial resolution 2° × 2° are adopted to examine the seasonal behavior of precipitation type. It is common to use the information of precipitation types extracted from EECRA together with the information of precipitation amount estimated from the TRMM product (e.g. Dai et al. 2007). According to Dai et al. (2007), the precipitation frequency for all precipitation types estimated from EECRA is generally comparable with that observed from the TRMM product.

Surface observations of cloud types and cloud amounts documented in the EECRA reports can be divided into three major groups based on altitude (Hahn and Warren 1999). High-level clouds (denoted by CH) form at heights above 6 km. The altitude of cloud base for middle-level clouds (i.e. CM) is between 2 and 6 km, and that for low-level clouds (i.e. CL) is up to 2 km. Here, we focus on the variations of CM and CL because only these two groups of clouds are likely to produce rain (Hahn and Warren 2007). Analyses of the seasonal behavior of clouds are based on a global gridded dataset (see footnote 2) constructed by Dai (2002) for the long-term mean 3-hourly EECRA-reported CM and CL.

Following Huang and Chan (2011), SEC in this study is defined as an area covering (110°–118°E, 21°–25°N). Huang and Chan (2011) examined the characteristics of PSEC in summer and suggested that the selected SEC area can be seen as a combination of continental rainfall regime and coastal rainfall regime which is characterized by an afternoon maximum in summer as identified by Kikuchi and Wang (2008). Hereafter, local time in SEC is universal time (UTC) + 8 h, e.g. 0800 h is 0000 UTC. The anomalies of a given variable at a specific synoptic time step (e.g. 0000 UTC) are computed by subtracting the daily means from available 3-hourly observations. The diurnal and semidiurnal harmonic components of the anomalies of each variable are obtained from Fourier analysis. The anomalies, diurnal (i.e. first harmonic) and semidiurnal (i.e. second harmonic) cycles of a given variable X is denoted by Δ(X), S1(X) and S2(X), respectively.

3 The seasonal variation of diurnal (S1) and semidiurnal (S2) precipitation

Figure 2a shows the temporal evolution of the mean 3-hourly PSEC (histogram) for the winter, spring, summer and autumn seasons of 1998–2009. Except during winter, PSEC frequently reaches its maximum value at the late afternoon (0600–0900 UTC; local time 1400–1700 h) with a minor peak in the early morning (2100–2400 UTC; local time 0500–0800 h), while the reverse is true for PSEC during winter. These characteristics are consistent with those found from rain gauge observations (e.g. Li et al. 2008),Footnote 3 confirming that TRMM observations are adequate for the analyses of sub-daily variations of PSEC (e.g. Chen et al. 2009). An examination on the contribution of S1(P)SEC and S2(P)SEC to ΔPSEC indicates that the combination of S1(P)SEC and S2(P)SEC (denoted as line with open circle in Fig. 2b) explains more than 90% of the total variability of ΔPSEC for all seasons (Table 1). In general, the time of occurrence of maximum PSEC (i.e. the primary peak in the early morning for winter and in the late afternoon for the other seasons) follows that of maximum S1(P)SEC, while the minor peak of PSEC (i.e. the secondary peak in the late afternoon for winter and in the early morning for the other seasons) occurs at the time with minimum S1(P)SEC and maximum S2(P)SEC. In other words, the formation of maximum and minor peak of PSEC is mainly determined by its S1 and S2 component, respectively (e.g. Zhou et al. 2008; Huang and Chan 2011). A better knowledge on the formation mechanism of S1(P)SEC and S2(P)SEC for different seasons, therefore, is important toward a better understanding of the sub-daily variations of PSEC.

Time evolution of mean 3-hourly PSEC (histogram in a), its related anomalies (i.e. ∆PSEC; blue solid line in b), diurnal harmonic (i.e. S1(P)SEC; red solid line in b), semidiurnal harmonic (i.e. S2(P)SEC; green dotted line in b), and a combination of S1 and S2 harmonic [denoted as black solid line with open circle in (b)] of PSEC in different seasons of the year. The lower x-axis is local time over SEC, which is universal time (UTC) +8 h

Some indications for the causes of seasonal changes in the sub-daily variations of PSEC are revealed from the long-term mean occurrence frequency of drizzle, showery and non-showery precipitation area-averaged over SEC for each of the seasons (Fig. 3a). It is noted that the contribution of drizzle type of precipitation to PSEC is much smaller than the other two types of precipitation. While the non-showery precipitation occurs much more frequently than the showery precipitation in the winter, the reverse is true in the summer. In the spring and autumn, although the occurrence frequency of showery precipitation is comparable to that of non-showery precipitation, the showery precipitation likely contributes more to the amount of PSEC than the non-showery precipitation because the intensity of showery precipitation is larger [~1.5–3 mm h−1 (Dai 2001a)] than that of non-showery precipitation (<1 mm h−1). In his study, Dai (2001b) noted that the maximum occurrence of showery and non-showery precipitation over land frequently appears at the afternoon and in the early morning respectively. This suggests that the change of predominant precipitation type from non-showery in the winter to showery in the other seasons (see Fig. 3a) could lead to seasonal change in the time of occurrence of maximum PSEC and S1(P)SEC (see Fig. 2).

a Seasonal mean frequency of occurrence for drizzle (yellow bar), non-showery (green bar) and showery (red bar) type of precipitation area-averaged over SEC. b Diurnal harmonic of DJF and JJA mean frequency of occurrence for showery (red solid line) and non-showery (green dotted line) type of precipitation. c is similar to b but for the semidiurnal harmonic component

Because the dominant sources of rainfall are different in winter and summer, one could expect rainfall variations to be determined by the process controlling the dominant source of precipitation. Evidence for above inference is given as follows. A comparison between S1(P)SEC (solid line in Fig. 2) and the diurnal variation of occurrence frequency of non-showery precipitation (hereafter S1(non-showery precipitation); dotted line in Fig. 3b) over SEC shows that their temporal evolutions are approximately in phase with each other in the winter, but out of phase with each other in the summer whereas the evolution of S1(P)SEC in the summer is in phase with that of S1(showery precipitation) (solid line in Fig. 3b). These features imply that S1(P)SEC in the winter is controlled by the S1(non-showery precipitation) whereas in the summer, as well as in the spring and autumns (not shown), S1(P)SEC is dominated by the S1(showery precipitation). Possible cause and the atmospheric conditions favorable for the formation of S1(non-showery precipitation) and S1(showery precipitation) are discussed in Sect. 4.

On the other hand, it is noted that S2(P)SEC tends to peak at both 0900 and 2100 UTC for all seasons (Fig. 2), implying that there might be some seasonal similarities in the formation mechanism of S2(P)SEC. Because the intensity of showery precipitation is larger than that of non-showery precipitation (Dai 2001a), when the occurrence frequency of showery precipitation is larger than (i.e. in summer; see Fig. 3a) or comparable to (i.e. in spring and autumn) the occurrence frequency of non-showery precipitation, the change in S2(P)SEC is found to be mainly dominated by the change in S2(showery precipitation). However, in winter, because the amplitude of S2(non-showery precipitation) is twice larger than the amplitude of S2(showery precipitation) (Fig. 3c) for the SEC region, to consider the change in S2(showery precipitation) only is not enough to explain the variation of S2(P)SEC in winter. It can be inferred from Dai (2001b) that the formation mechanism of non-showery precipitation is different from that of showery precipitation. However, because the evolutions of S2(non-showery precipitation) and S2(showery precipitation) are approximately in phase with each other in all seasons (see Fig. 3c for winter and summer; not shown for spring and autumn), there might be some close relationship between their formation mechanism. These inferences are examined in Sect. 5.

4 Causes of seasonal change in the diurnal cycle of precipitation

According to the EECRA’s documentation,Footnote 4 showery and non-showery precipitation are generated by CL and CM, respectively. Previous studies have suggested that, in response to diurnal solar heating, the maximum occurrence of moist convective precipitation and clouds (i.e. showery precipitation and CL) is observed in the afternoon over land but in the early morning over the ocean (Chen et al. 1999; Dai and Deser 1999). If this is true, the value of S1(showery precipitation) and S1(CL) at 0900 UTC/1700 h should be positive over SEC, but negative over the western North Pacific. While the spatial pattern for the summer seasons (Fig. 4b) (also for the spring and autumn seasons; not shown) is consistent with this assertion, the values of S1(showery precipitation) and S1(CL) over SEC at 0900 UTC/1700 h for the winter seasons are negative (Fig. 4a).

Diurnal harmonic of a DJF and b JJA mean frequency of occurrence for showery precipitation (contours) superimposed with the low cloud amount (i.e. CL; shadings) at 0900 UTC (i.e. 1700 h for SEC). c and d is similar to a and b but for the non-showery precipitation superimposed with the middle level cloud amount (i.e. CM). The contour interval of a–d is 0.2%. The mountain areas in a–d are blocked

Huang et al. (2010) examined the seasonal variation of diurnal atmospheric circulation and found that the diurnal atmospheric circulation over East Asia and the western North Pacific, which is generally characterized by upward motions over land and downward motions over the ocean at the afternoon in the summer (Dai and Deser 1999), shifts westward in the winter. Such a seasonally-varying diurnal atmospheric circulation, which has been found to be induced mainly by the seasonal changes in diurnal pressure tidal wave—a wave generated by the periodic incoming solar heating in the atmosphere, has been suggested as a major factor in resulting the winter S1(P)SEC with a morning maximum and a afternoon minimum, and the summer S1(P)SEC with a afternoon maximum and a morning minimum (Huang et al. 2010). Note also from Fig. 4a that the negative values of S1(showery precipitation) and S1(CL) over the western North Pacific seem to extend westward to cover the area of SEC in the winter. The appearance of negative values of S1(showery precipitation) and S1(CL) over SEC in Fig. 4a, therefore, can be seen as a new evidence for supporting Huang et al. (2010)’s finding.

Seasonal changes in the diurnal atmospheric conditions that favor the formation of S1(showery precipitation) and S1(CL) over SEC are shown in Fig. 5d–e. In general, positive values of S1(CL) over SEC (Fig. 5b) occur at the time when there are active upward motion (Fig. 5d) and increase in low-level wind convergence (not shown). In Huang et al. (2010), it is demonstrated that such kind of increase in low-level wind convergence would lead to an increase in vertical integrated atmospheric moisture convergence [i.e. S1(−∇·Q) > 0; Fig. 5e] over SEC. The role of S1(−∇·Q) in contributing to the change of S1(P) over East Asia has been examined in Chen (2005) through the diagnosis of water vapor budget equation.Footnote 5 Chen (2005) has showed that the variation of S1(P) over the East Asian monsoon region is mostly contributed by its related change in S1(−∇·Q) and rarely by the change in evaporation or water vapor tendency. Here, a comparison between Fig. 5a, e further indicates that the amplitude of S1(P)SEC is approximately equal to the amplitude of S1(−∇·Q)SEC for all seasons, implying that the change in S1(P)SEC largely depends on the change in S1(−∇·Q)SEC. Detailed discussions regarding to the relationship between S1(−∇·Q)SEC and S1(P)SEC have also been made in Huang et al. (2010). Note that because the seasonal evolution of S1(P)SEC (Fig. 5a) varies approximately in phase with that of S1(CL) induced by the diurnal moist convection processes, formation mechanism of S1(non-showery precipitation) and S1(CM), which are also important to S1(P)SEC in the winter (see discussions of Fig. 2), has often been neglected when studying the possible causes of S1(P)SEC (e.g. Huang et al. 2010).

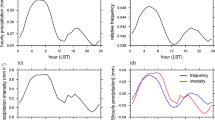

Diurnal harmonic of the average over SEC of a precipitation amount, b low cloud amount, c middle cloud amount, d vertical velocity at 925-hPa [denoted by −ω(925 hPa)], e convergence of vertically-integrated atmospheric water vapor flux (i.e. −∇·Q) and f relative humidity at 650 hPa (~3.5 km above the surface). Here, \( - \nabla \cdot \overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}}{\text{Q}} = - \nabla \cdot \left( {\int_{{{\kern 1pt} \,{\text{P}}0}}^{{\,{\kern 1pt} 300hPa}} {\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\rightharpoonup}$}}{{\text{V} q}}\;{\text{dp}}} } \right) \), where V denotes the horizontal wind, q is the specific humidity, and p is the pressure level. The contour interval for a to f is 2.2 × 10−2 mm h−1, 0.5%, 0.5%, 2.5 × 10−4 hPa s−1, 2.2 × 10−2 mm h−1, and 1% respectively

For S1(non-showery precipitation) and S1(CM) over SEC, their maximum generally appears in the early morning, while their minimum occurs at the late afternoon in all seasons (Figs. 4c–d, 5c). Dai (2001b) has suggested that the non-showery precipitation often occurs when the environment has high relative humidity (RH). Consistent with this suggestion, the seasonal evolution of S1(CM) over SEC (Fig. 5c) is found to be in phase with that of S1(RH) at the middle-levels (e.g. 650 hPa ~3.5 km above SEC; Fig. 5f). For S1(RH), its variation at the low-levels generally depends upon the diurnal variation of surface air temperature (e.g. Dai 2001b). When the atmospheric water vapor content is the same during a day, the longwave radiative cooling at night will lead to a decrease in surface air temperature and an increase in the low-level S1(RH) in the early morning. Because the late night cooling is not only revealed at the low-levels but also at the middle-levels (see Fig. 6a–b; from 800 to 500 hPa ~2–5 km above SEC), it is reasonable to find that the middle-level S1(RH)SEC reaches its maximum value at the time similar to what has been found for the low-level S1(RH)SEC (see Fig. 6c–d). Such an increase in the middle-level S1(RH)SEC, induced by the middle-level nighttime cooling, likely provides a favorable environmental condition for the formation of maximum S1(CM) and S1(non-showery precipitation) over SEC in the early morning for all seasons.

On the other hand, it is noted from Fig. 5a of Huang et al. (2010) that the atmospheric condition over SEC in the winter morning is more moist and unstable at the middle-levels than at the low-levels (not shown). This feature, which has not been explained by Huang et al. (2010), can now be linked to that S1(P)SEC in the winter morning is mainly dominated by the middle-level clouds/non-showery precipitation (see Fig. 3b). Mechanisms related to the formation of middle-level clouds and non-showery precipitation discussed above, therefore, deserve attention of future observational or modeling studies interested in the seasonal variation of S1(P)SEC.

Despite the seasonal difference of the day-night contrast of PSEC, it is noted from Fig. 2a that both the afternoon and early morning rainfall peaks exist in all seasons. For the afternoon rainfall peak, it is minor in winter but major in the other seasons. Thus, the temporal evolution of PSEC in winter (Fig. 2a) might be also seen as a result of the dissipation of afternoon rainfall (e.g. Huang et al. 2010) which leaves only the early morning rainfall peak. In Huang and Chan (2011), the mechanism for the early morning rainfall peak in summer involves thermal advection between the SCS and SEC, which promotes convection over the SEC, with ensuing positive feedback through the radiative heating/cooling. To know if this mechanism is also true for the other seasons, we examine the seasonality for the S1 harmonic of atmospheric horizontal thermal advection [i.e. S1(−V·∇T)] over SEC—a heating them that mainly controlled by the change of S1 of wind field and horizontal temperature gradient between SEC and SCS (Huang and Chan 2011).

As seen from Fig. 7a, the low-level S1(−V·∇T) at 1800 UTC is positive over SEC in all seasons. For the occurrence of late night low-level southerly wind anomaly over SEC, its formation mechanism likely depends strongly on the East Asia topography (e.g. Yu et al. 2009). In general, air near the Tibetan mountains is cooler than that near the SEC due to surface radiational cooling of the ground at night. This causes a pressure gradient to flow from the costal area to the area near the Tibetan mountains. Because of the Coriolis force, the westward-moving air likely gives the diurnal wind anomalies a strong southerly component east of the Tibetan mountains. This low-level southerly wind anomaly, which is strongest at 1800–2100 UTC (see contours of Fig. 7b), would then transport air from the warmer and moister SCS to SEC and promotes early morning convection over SEC. Because the afternoon rainfall over SEC is weak in the winter seasons, the diurnal rainfall in winter would be mainly dominated by the early morning maximum. The cause of weak afternoon rainfall in winter might be related to the seasonal change in solar heating and diurnal atmospheric circulation as what has been found in Huang et al. (2010).

a The long-term mean of diurnal harmonic of 925-hPa horizontal thermal advection S1(−V·∇T) at 1800 UTC for four seasons. The wind vectors of S1[V(925-hPa)] at 1800 UTC are added in a and the mountain areas are blocked. b The temporal-vertical evolution of S1(−V·∇T) (shadings) and its related meridional wind speed (contours) area-averaged over SEC. The contour interval of b is 0.15 m s−1

5 Causes of seasonal changes in semidiurnal cycle of precipitation

Next, we examine possible causes of S2(P)SEC for different seasons. Some indications for the causes of S2(P)SEC are revealed in Fig. 8, a figure similar to Fig. 5 but for the semidiurnal component. It is noted that the maximum of S2(CL) over SEC (Fig. 8b) occurs at the time with maximum S2[−ω(925 hPa)]—i.e. semidiurnal harmonic of vertical velocity at 925 hPa (Fig. 8c)—and maximum S2(−∇·Q)—i.e. semidiurnal harmonic of vertical integrated water vapor flux convergence (Fig. 8e), suggesting that the semidiurnal moist convection process is important to the formation of S2(showery precipitation) over SEC. For S2(CM) over SEC (Fig. 8c), its seasonal evolution is in-phase with that of S2(RH) at 650 hPa (Fig. 8f), implying that the variation of S2(RH) at the middle-levels might be important to the formation of S2(non-showery precipitation) over SEC.

Similar to Fig. 5 but for the semidiurnal harmonic component. The contour interval for a–f is 2.2 × 10−2 mm h−1, 0.2%, 0.2%, 2.5 × 10−4 hPa s−1, 2.2 × 10−2 mm h−1, and 0.3% respectively

Note also from Fig. 8 that S2(CM) has similar evolution as S2(CL), suggesting that there might be some linkage between their formation mechanisms [i.e. S2(RH) and S2 of moisture convergence]. Possible explanations for this linkage can be inferred from a comparison between the vertical profiles of S2(T)SEC, S2(RH)SEC and S2(−∇·Vq)SEC (i.e. the convergence of moisture flux at specific pressure level). As seen from Fig. 9a, S2(T)SEC reaches to its maximum at 0900 and 2100 UTC mainly for the levels below 600 hPa. Theoretically, such an increase in temperature would induce a decrease in S2(RH)SEC at 0900 and 2100 UTC, which is different to what has been revealed in Fig. 9c–d, for the levels below 600 hPa. Because RH depends not only on the temperature but also on the amount of moisture available, it is likely that an increase in S2(−∇·Vq)SEC (Fig. 9e–f) leads to an increase in the amount of moisture available which in turn causes the maximum of S2(RH)SEC at 0900 and 2100 UTC. This explains why the phase of S2(RH)SEC at the levels below 600 hPa is similar to the phase of S2(−∇·Vq)SEC. As for S2(RH)SEC at the levels above 600 hPa, its change likely depends more on the change of S2(T)SEC (i.e. cooling at 0900 and 2100 UTC) than the change of moisture [i.e. S2(−∇·Vq)SEC < 0].

Similar to Fig. 6 but for the semidiurnal harmonic component of a TSEC, c RHSEC, and e (−∇·Vq; moisture convergence) in the winter seasons. b, d, f is similar to a, c, e, respectively, but for the summer seasons. The contour interval for a–b, c–d, and e–f is 0.1°C, 0.3%, and 2.5 × 10−7 g/kg s−1, respectively

On the other hand, it should be mentioned that it is not necessary for the magnitude of S2(CL) or S2(CM) shown in Fig. 8c–d to have a similar magnitude as their formation mechanism shown in Fig. 8e–f. For example, if CL is dominated by stratus type of low cloud (with smaller moisture convergence) in winter but by cumulus type of low cloud (with larger moisture convergence) in summer, the value of area-averaged CL over SEC would be larger in winter than in summer but its related change of moisture convergence would have a smaller magnitude in winter than in summer. So the examinations of S2(CL) and S2(CM) can not be used to indicate the seasonal change in the magnitude of their related precipitation, but can be used to infer that the time for the occurrence of maximum S2(CM) and S2(CL) is similar to each other. An important question raised here is what causes their formation mechanisms to be more active at the same time (i.e. peak at 0900 and 2100 UTC) for all seasons.

In Huang and Chan (2011), the semidiurnal variation of land-sea differential heating between SEC and South China Sea (hereafter SCS; dotted boxed area in Fig. 1a) has been found to play a major role in driving the semidiurnal moist convection process in the summer. Because there is no seasonal difference in the phase of S2(CL) and S2(CM) over SEC (see Fig. 8b–c), it is likely that the effect of clouds on radiation would result in a seasonal similarity on the phase of semidiurnal net radiative heating/cooling over SEC. Moreover, the mechanism proposed by Huang and Chan (2011) for the cause of semidiurnal moist convection process in the summer might also work in the other seasons.

To verify above inferences, we examine the semidiurnal variation of net radiative heating/cooling area-averaged over SEC and SCS [denoted by S2(∂TR/∂t)SEC and S2(∂TR/∂t)SCS respectively] at multiple levels. Following Huang and Chan (2011), (∂TR/∂t) is defined as a combination of temperature tendency due to shortwave and longwave radiation, which can be extracted directly from the 3-hourly GEOS5 datasets. It is found that the low-level S2(∂TR/∂t)SEC tends to peak at both 0600 and 1800 UTC [i.e. 3 h before the time of the two maximum peaks of S2(P)SEC] for all seasons (not shown). Throughout the all 12-months of the year, S2(∂TR/∂t) at both 0600 and 1800 UTC is larger over SEC than over SCS at the low-levels, while a reverse pattern is being observed at the upper-levels (Fig. 10). Such a change in S2(∂TR/∂t) at 0600 and 1800 UTC would lead to the change in S2(TR) at 0900 and 2100 UTC respectively [i.e. the time with maximum S2(P)SEC] through Eq. 1,

where TR is the temperature change induced by net radiative heating/cooling and with the temporal resolution of GEOS5, a 3-h time interval is used in Eq. 1 for the time integration. In other words, the semidiurnal land-sea differential heating between SEC and SCS shown in Fig. 10 likely leads to a larger semidiurnal thermal instability [i.e. S2(∂TR/∂p), p is pressure] over SEC than over SCS at 0900 and 2100 UTC for all seasons.

Monthly mean of S2(∂TR/∂t) area-averaged over Southeast China (SEC; solid boxed area in Fig. 1a) (solid line) and South China Sea (SCS; dotted boxed area in Fig. 1a) (dotted line) at 1800 UTC for all 12-months of the year from January to December. Note that the monthly means of S2(∂TR/∂t) at 0600 UTC have the same profiles as S2(∂TR/∂t) at 1800 UTC

An examination of the S2 harmonic of 925-hPa moist instability [denoted by S2(∂θe/∂p), positive is unstable] at 0900 and 2100 UTC (contours in Fig. 11a) verifies that the environment is more unstable over SEC than over SCS for all seasons. This explains why the upward motion is stronger, i.e. larger positive values of S2[−ω(925 hPa)] (shadings in Fig. 11a), over SEC than over SCS at 0900 and 2100 UTC. In response to such an atmospheric circulation change, more water vapor flux is transporting from SCS to SEC on the semidiurnal timescale (Fig. 11b). This is the reason for S2(−∇·Q) over SEC to peak at both 0900 and 2100 UTC for all seasons (see Fig. 8e). Because the change in middle-level S2(RH)SEC is found to be mainly controlled by the change in middle-level S2 of moisture convergence which has similar phase evolution as low-level S2 of moisture convergence (see Fig. 9), the S2(CM) might be linked to the S2(CL) through the detrainment from moist convection. This explains why the evolution of S2(non-showery precipitation) and S2(showery precipitation) over SEC are approximately in phase with each other. As a result of this feature, there is no seasonal transition in the phase of S2(P)SEC.

a Mean semidiurnal harmonic of 925-hPa moist instability [i.e. S2(∂θe/∂p); contours] and vertical velocity [i.e. S2(−ω); shadings] at 0900 and 2100 UTC [i.e. the time of the occurrence of maximum S2(P)SEC]. b Mean semidiurnal harmonic of convergence of vertically integrated atmospheric water vapor flux, i.e. S2(−∇·Q) (contours), superimposed with S2(P) (shadings) at 0900 and 2100 UTC. The vectors of the convergence of water vapour flux are added in b. The contour interval for a and b is 10−2 K hPa−1 and 2 × 10−2 mm h−1, respectively. The color scale of a and b is given in their right bottom. The mountain areas are blocked in a–b

6 Summary

In this study, causes of the seasonal changes in sub-daily rainfall variability in Southeast China are examined based on the analyses of changes in precipitation type, cloud type and their associated atmospheric thermodynamic conditions. It is found that the seasonal transition of predominant precipitation type/cloud type from showery precipitation/low-level cloud in the summer, spring and autumn to non-showery precipitation/middle-level cloud in the winter is one of the main causes for the seasonal changes in the phase of S1(P)SEC from a peak in the late afternoon to one in the early morning. Analyses suggest that the S1(showery precipitation) is the major contributor to S1(P)SEC in the summer, spring and autumn. In contrast, S1(P)SEC in the winter is mainly contributed by the S1(non-showery precipitation). For the formation mechanism of S1(showery precipitation) and S1(non-showery precipitation) over SEC, they are linked to the diurnal variation of moist convection process and middle-level relative humidity respectively.

One the other hand, it is suggested that the difference between sub-daily rainfall variability in winter and summer might be also seen as that the main daytime moist convective activity is largely absent in winter, leaving only the early morning activity which is much weaker (but may still feedback on the non-showery precipitation). Analysis of the formation mechanism of early morning rainfall over SEC further indicates that the late night thermal advection would promote early morning convection over SEC, and this feature can be observed in all seasons.

Examinations of the temporal evolution of S2(P)SEC for four seasons show that they change approximately in phase because both the moist-convection-induced S2(showery precipitation) and the high-relative-humidity-induced S2(non-showery precipitation) over SEC have similar temporal evolution in all seasons. Diagnoses on the atmospheric conditions further indicate that the semidiurnal variation of land-sea differential heating between SEC and SCS, which tends to produce a relative unstable environment in SEC at 0900 and 2100 UTC, induces more water vapor flux transporting from SCS into SEC to support the occurrence of maximum S2(P)SEC at 0900 and 2100 UTC. This result is true for all seasons despite the seasonal transition of predominant precipitation type/cloud type.

Note, although this study is a follow-up study of our previous works (Huang et al. 2010; Huang and Chan 2011), there are several points that make this study is important. First, the seasonal change of precipitation type/cloud type in affecting the sub-daily rainfall variations over SEC have not been considered in our previous works. Second, in Huang et al. (2010), the change in nighttime relative humidity and thermal advection have not been taken into account as possible causes for explaining the early morning maximum of S1(P)SEC in winter. Third, in Huang and Chan (2011), not only the change of S2(P)SEC has not been linked to the change of S2(RH)SEC, the seasonality of S2(P)SEC has also not been mentioned. All of these issues are now examined in the current study. Results of this study, therefore, are important information for future studies interested in examining the sub-daily rainfall variation in SEC.

Notes

Data is available at http://www.cgd.ucar.edu/cas/adai/data-dai.html.

Note, the data used in Zhou et al. (2008) is TRMM 3B42 and in the present study is TRMM 3G68. For PSEC, the variations derived from these two data versions are identical to those from the rain-gauge observations.

Information is available at http://cdiac.ornl.gov/ftp/ndp026c/ndp026c_readme.txt.

\( {\text{P}} = {\text{E}} + ( - \nabla \bullet {\text{Q}}) + ( - \frac{{\partial {\text{W}}}}{{\partial {\text{t}}}}), \) where W and E is the total precipitable water and the evaporation respectively.

References

Chan JCL, Ng MH (1993) Morning showers over Hong Kong during summer. Bull Hong Kong Meteor Soc 3:14–25

Chen TC (2005) Variation of the Asian monsoon water vapor budget: interaction with the global-scale modes. In: Wang B (ed) The Asian monsoon. Springer, Berlin, pp 417–458

Chen TC, Yen MC, Hsieh JC, Arritt RW (1999) Diurnal and seasonal variations of the rainfall measured by the automatic rainfall and meteorological telemetry system in Taiwan. Bull Amer Meteor Soc 80:2299–2312

Chen G, Sha W, Iwasaki T (2009) Diurnal variation of precipitation over southeastern China: spatial distribution and its seasonality. J Geophys Res 114:D13103. doi:10.1029/2008JD011103

Chen H, Yu R, Li J, Yuan W, Zhou T (2010) Why nocturnal long-duration rainfall presents an eastward delayed diurnal phase along the Yangtze River. J Climate 23:905–917

Dai A (2001a) Global precipitation and thunderstorm frequencies. Part I: seasonal and interannual variations. J Climate 14:1092–1111

Dai A (2001b) Global precipitation and thunderstorm frequencies. Part II: diurnal variations. J Climate 14:1112–1128

Dai A (2002) Evaluating GCMs using diurnal variability. In: Proceedings of the AMS 13th symposium on global change and climate variations, 14–17 Jan. 2002, Orlando, FL, pp 143–145

Dai A, Deser C (1999) Diurnal and semidiurnal variations in global surface wind and divergence fields. J Geophys Res 104:31109–31125

Dai A, Lin X, Hsu KL (2007) The frequency, intensity, and diurnal cycle of precipitation in surface and satellite observations over low- and mid-latitudes. Clim Dyn 29:727–744

Haddad ZS, Smith EA, Kummerow CD, Iguchi T, Farrar MR, Durden SL, Alves M, Olson WS (1997a) The TRMM ‘day-1’ radar/radiometer combined rain-profiling algorithm. J Meteor Soc Japan 75:799–809

Haddad ZS, Short DA, Durden SL, EImS Hensley, Grable MB, Black RA (1997b) A new parametrization of the rain drop size distribution. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens 35:532–539

Hahn CJ, Warren SG (1999) Extended edited cloud reports from ships and land stations over the globe, 1952–1996. Tech. Rep. NDP-026C, Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Department of Energy, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, pp 79

Hahn CJ, Warren SG (2007) A gridded climatology of clouds over land (1971–96) and ocean (1954–97) worldwide. Tech. Rep. NDP-026E, Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Department of Energy, Oak Ridge, Tennessee, pp 75

Hong Y, Hsu KL, Sorooshian S, Gao X (2005) Improved representation of diurnal variability of rainfall retrieved from the tropical rainfall measurement mission microwave imager adjusted Precipitation estimation from remotely sensed information using artificial neural networks (PERSIANN) system. J Geophys Res 110:D06102. doi:10.1029/2004JD005301

Houze RA (1993) Cloud dynamics. Academic Press, San Diego, p 573

Huang WR, Chan JCL (2011) Maintenance mechanisms for the early-morning maximum summer rainfall over Southeast China. Q J R Meteorol Soc 137:959–986. doi:10.1002/qj.815

Huang WR, Chan JCL, Wang SY (2010) A planetary-scale land–sea breeze circulation in East Asia and the western North Pacific. QJR Meteorol Soc 136:1543–1553. doi:10.1002/qj.663

Kikuchi K, Wang B (2008) Diurnal precipitation regimes in the global tropics. J Climate 21:2680–2696

Li J, Yu R, Zhou T (2008) Seasonal variation of the diurnal cycle of rainfall in southern contiguous China. J Climate 21:6036–6043

Ramage CS (1952) Diurnal variation of summer rainfall over east China, Korea and Japan. J Atmos Sci 9:83–86

Rienecker MM, Suarez MJ, Todling R, Bacmeister J, Takacs L, Liu HC, Gu W, Sienkiewicz M, Koster RD, Gelaro R, Stajner I, Nielsen JE (2008) The GEOS-5 data assimilation system—documentation of versions 5.0.1, 5.1.0, and 5.2.0. Technical Report Series on Global Modeling and Data Assimilation, p 27

Simpson JS, Kummerow C, Tao WK, Adler RF (1996) On the tropical rainfall measuring mission (TRMM). Meteorol Atmos Phys 60:19–36

WMO (World Meteorological Organization) (1988) Manual on codes, vol. 1. WMO Publ. 306, pp 203

Yang S, Smith EA (2006) Mechanisms for diurnal variability of global tropical rainfall observed from TRMM. J Climate 19:5190–5226

Yin S, Chen D, Xie Y (2009) Diurnal variations of precipitation during the warm season over China. Int J Climatol 29:1154–1170

Yu R, Zhou T, Xiong A, Zhu Y, Li J (2007a) Diurnal variations of summer precipitation over contiguous China. Geophys Res Lett 34:L01704. doi:10.1029/2006GL028129

Yu R, Xu Y, Zhou T, Li J (2007b) Relation between rainfall duration and diurnal variation in the warm season precipitation over central eastern China. Geophys Res Lett 34:L13703. doi:10.1029/2007GL030315

Yu R, Li J, Chen H (2009) Diurnal variation of surface wind over central eastern China. Clim Dyn 33(7–8):1089–1097

Yu R, Yuan W, Li J, Fu Y (2010) Diurnal phase of late-night against late-afternoon of stratiform and convective precipitation in summer southern contiguous China. Clim Dyn 35(4):567–576

Zhao Z, Leung LR, Qian Y (2005) Characteristics of diurnal variations of precipitation in China for the recent years. CLIVAR Exchanges, No. 3, International CLIVAR Project Office, Southampton, United Kingdom, pp 24–26

Zhou T, Yu R, Chen H, Dai A, Pan Y (2008) Summer precipitation frequency, intensity, and diurnal cycle over China: a comparison of satellite data with rain gauge observations. J Climate 21:3997–4010

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the projects of TRMM, EECRA and GEOS5 for providing data. Thanks are extended to Dr. Aiguo Dai who shares his global gridded data of EECRA observations online at http://www.cgd.ucar.edu/cas/adai/data-dai.html. In addition, we thank anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions which greatly improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, WR., Chan, J.C.L. Seasonal variation of diurnal and semidiurnal rainfall over Southeast China. Clim Dyn 39, 1913–1927 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-011-1236-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-011-1236-5