Abstract

Object

Desmoplastic infantile gangliogliomas (DIGs) and desmoplastic infantile astrocytomas (DIAs) are tumors typical of the infantile age. A large size, with a mixed solid and cystic component, clinical presentation with progressing signs of increased intracranial pressure, a prominent benign desmoplastic structure at histological examination, and a favorable clinical course in the majority of cases are the prominent features of these tumors. The objective of the present paper was to review the pertinent literature on the topic together with our personal experience, with the aim of an updated review of the subject.

Results and conclusions

Only 28 papers are present in the literature devoted to DIGs and DIAs, most of them reporting on single cases or small series, with a total of 107 patients aged from 5 days to 48 months with a slight male prevalence. Most of the reported cases refer to supratentorial and hemispheric locations, a few cases involving the hypothalamic region, the posterior fossa, and the spinal cord. The typical MRI appearance is of large mixed solid and cystic tumors with a spontaneous hyperintense T2 appearance of the solid part which also shows a strong contrast enhancement. Mixed ganglionic and astrocytic cells are identifiable in DIGs, whereas DIAs are typically featured by the exclusive presence of glial cells. In both cases, more primitive cells may be observed, which present a higher number of mitoses and these areas can mimic the features of malignant astrocytomas. Surgery represents the treatment of choice; however, radical removal has been reported as possible only in around 30 % of the cases: the low age of the patients together with their low weight and the large size of and the hyper-vascularized structure of the tumors represent the main factors limiting surgery. Pure observation is considered as first choice in children undergoing a partial/subtotal tumor resection, chemotherapic regimens being considered in cases of recurrences after a second look surgery. Long-term prognosis is favorable with mortality being related mostly to the rare midline (i.e., hypothalamic) locations, which beyond the functionally relevant site, tend to have an unusually more aggressive histological behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 1984, Taratuto et al. [29] described for the first time a group of infantile brain tumors with astrocytic component that took the name of superficial cerebral astrocytomas. After few years, in 1987, Vandenberg et al. [32, 33] followed the work of Taratuto et al. uniting under the name of desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma (DIG) those brain tumors that, though rare, were characterized by the following: (1) divergent astrocytic and ganglionic differentiation, (2) prominent desmoplastic stroma, (3) voluminous size, (4) evidence of a cystic component, (5) presentation within the 18 months of life, and (6) good prognosis.

Later, a distinction based on histological features has been made between tumors with clear ganglionic differentiation that maintained the name of DIG and tumors with similar features, but exclusive astrocytic cellular representation that took the name of desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma (DIA).

Frequency and distribution

DIGs represent 0.5–1 % of brain tumors with a clear predominance of males over females. Typically, the diagnosis is made before the second year of life, with the highest peak in patients aged less than 18 months [26]; however throughout the literature, non-infantile cases of desmoplastic gangliogliomas are reported [11–18]. On the other hand, DIAs are rarer than DIGs [7] (0.3 % of brain tumors); though they affect patients of the same age compared with DIGs, do not have such a strong preponderance for males as the one seen in cases of desmoplastic infantile gangliogliomas.

Location and symptoms (Table 1)

DIGs and DIAs are supratentorial tumors in the vast majority of cases, for the most part hemispheric in location and without side prevalence. Multiple lobes are commonly involved with a higher incidence for the frontal and parietal regions [4–23]. In a minority of cases, the suprasellar region, the posterior cranial fossa, or the spinal canal may be involved [10]. Even in infants where the sutures are still open, the duration of the clinical history is rather short (3–6 months) due to the relevant volume that these tumors might achieve. Classical symptoms include rapid head growth (60 % of cases), often associated to a bulging of the anterior fontanel, sunset sign, and bulging of the bone structures over the tumor [1, 4, 11, 26, 28]. In older children, a longer clinical history has been reported (6–9 months) with presenting symptoms typical of intracranial hypertension often associated with focal neurological signs [26]. Differently from dysembryoblastic neuro-epithelial tumors (DNET), seizures represent the clinical onset only in 20 % of the cases and due to the compensatory mechanisms which are typical of the infantile age, consciousness impairment is relatively rare [11].

Histopathology

These tumors are usually very large at diagnosis with uni- or multiloculated cysts filled with clear or xanthochromic fluid. The superficial portion is primarily extra-cerebral, involving the leptomeninges and superficial cortex, and is commonly attached to the dura [29, 32, 33].

The main histological feature of both DIGs and DIAs is the presence of desmoplastic features such as a stroma rich in collagen and spindle elongated fibroblastic elements intermixed with surrounding collagen and reticulin fibers. The element differentiating DIGs and DIAs is the cellular component; in fact, DIGs show a prevalence of neuronal elements whereas DIAs show an exclusive astrocytic component.

Neuronal cells in DIGs range from atypical ganglion cells to small polygonal cells with a more primitive cell compound. On the other hand, in DIAs, the astrocytic population is moderately pleomorphic ranging from elongated to polygonal cells [5, 7, 20, 26]. The neuronal component of DIGs generally stain positive for NSE, synaptophysin, and sometimes for neurofilament while DIAs astrocytes show intense immunoreactivity to GFAP. EMA stain is usually negative [5].

Though reaching in most cases the cortical surface, there is a strong demarcation between the tumor and the normal cortex even if Virchow-Robin spaces are often filled with neoplastic cells.

Mitotic activity is low and limited to the primitive cells compound, Ki67 ranging between 0.5 and 15 %.

Unusual histological features include rabdoid components inside the stroma [2], melanocytic differentiation [3], and ceruloplasmin secretion [16].

Genetics

Limited information is available concerning the genetics of DIGs and DIAs, both due to the relatively limited number of cases described as well as the lack of association of this kind of tumors with cancer predisposition syndromes.

When analyzed, normal karyotype or non-clonal abnormalities have been found. Genomic losses have been found at 5q13.3, 21q22.11 (TMEM50B, DNAJC28), and 10q21.3 both in DIGs and DIAs whereas high-copy gains seem to be absent or extremely rare. Although EGFR and MYCN amplifications have been previously described in DIGs, no amplification of genes that are commonly observed in pediatric high-grade gliomas (EGFR, MYCN, PDGFRA) are present [12].

As a possible differentiating feature among the two entities, chromosomal gains affecting the region harboring the BRAF protein have been described in the desmoplastic area of DIGs [12–17], but are absent in DIAs.

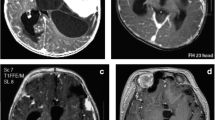

Neuroimaging (Fig.1)

DIG of the hypothalamic region, MR appearance. a Coronal, sagittal, and axial T2 images: the solid part of the tumor appears as iso-hyperintense due to its extensive desmoplastic component; the cystic part is typically multiloculated. b Coronal, sagittal, and axial T1 images after gadolinium injection: the solid part of the tumor is intensively enhancing

Almost always DIGs and DIAs have a solid superficial component associated with a uni- or multiloculated cyst [4–7].

At CT scan, the solid part appears as isodense or slightly hyperdense with strong enhancement after iodine contrast administration; the cystic component is most frequently hypodense or isodense according to the relatively variable proteic content; calcifications or hemorrhages are usually absent [4–20], though occasionally described in children presenting with acute symptoms [8–31].

At MRI, the solid component and the septa that might be found in the context of the cysts of DIGs appear as hypointense both in T1 and T2 weighted sequences; the cystic content is classically hypointense in T1 sequences and hyperintense in T2. After the i.v. administration of gadolinium, the solid part of the tumor and the adjacent dura mater, when interested, enhance strongly [20–31].

While having similar appearance in unenhanced MRI, DIAs are often characterized by non-homogeneous contrast captation after contrast administration, due to the frequent presence of areas of cavitation inside the solid part [7].

T2 hyperintensity and lower age are the main features allowing to differentiate DIG/DIAs from gangliogliomas and pleomorphic xanto-astrocytomas. DNETs, usually affecting older patients, might be differentiated also because of their lower size and the lack of contrast enhancement [26].

Treatment (Table 1)

The mainstay of treatment of DIGs/DIAs is surgery. Intraoperatively, they are characterized by a firm texture, due to desmoplasia, and a wide cortical contact of the cystic components.

Total removal however might be hampered by the frequent strict adhesion of the tumor to the cortex and the dura, which represent a limiting factor, particularly in the case of tumors involving eloquent or deep areas of the brain and/or extending to the basal dura or the sagittal sinus. Furthermore, the typical occurrence of these tumors in younger ages render intraoperative blood loss itself a factor limiting the extension of the tumor removal, which in selective cases should be staged [5–26].

When partial resection is achieved, a careful follow-up is mandatory to monitor potential tumor re-growths; however, similar to other forms of low-grade tumors, long relapse-free intervals have been described even after partial resections, suggesting the potential for tumor residual stabilization after a partial tumor removal [11, 32, 33].

Complementary treatments are primarily not advocated unless recurrence or residual tumor growth has been documented; in such cases, if surgery is not an option, chemotherapy might be considered. Concerns exist about the role of radiotherapy as clear benefits have not been demonstrated [5, 10, 11], leading actually to consider it only in patients, aged more than five, as a last resort in recurring tumors after surgery and chemotherapy [26].

Prognosis

In the vast majority of cases, DIGs and DIAs are associated with a long-term good prognosis and recurrence-free intervals that range from 6 months to 14 years. An aggressive behavior has been occasionally described and appears more frequent in children with DIAs than in those with DIGs [10, 14, 22, 27]. Suggestive histological markers in these cases are not different from the ones seen in other forms of aggressive supratentorial gliomas, including necrosis, mitosis, neo-vascularization, and the evidence at diagnosis of cerebrospinal metastasis [10]. The higher incidence of malignancies among DIAs is likely to be connected with the prevalent astrocytic component of these tumors, which show an easier tendency to a malignant transformation, similar to what it can be seen in other kind of gliomas compared with tumors coming from neuronal structures both in children and adults.

From the review of the pertinent literature, the mortality rate of patients affected by DIGs/DIAs is around 6 % (6 of 107 cases). Respiratory insufficiency and hypothalamic compromise are reported as the cause of death in half of the cases (3 of 6) [10, 14, 27]; all of these children harbored tumors primarily located at the level of the hypothalamus; a more aggressive histological appearance was described in all of them. Tumor spreading was present at diagnosis in a further case in spite of a typical histological appearance, whereas the remaining two cases of mortality were due to general causes unrelated to the tumor location or its biological behavior [29–31].

References

Aida T, Abe H, Itoh T, Nagashima K, Inoue K. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma—case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1993 Jul;33(7):463–466.

Alghamdi S, Castellano-Sanchez A, Brathwaite C, Shimizu T, Khatib Z, Bhatia S. Strong desmin expression in a congenital desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma mimicking pleomorphic rhadomyosarcoma: a case report including ultrastructural and cytogenetic evaluation and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst 2012 Dec;28(12):2157–2162. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1886-6.

Antonelli M, Acerno S, Baldoli C, Terreni MR, Giangaspero F. A case of melanotic desmoplastic ganglioglioma. Neuropathology 2009 Oct;29(5):597–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2009.01041.x.

Avci E, Oztürk A, Baba F, Torun F, Karabağ H, Yücetaş S. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma: case report. Turk J Pediatr 2008 Sep-Oct;50(5):495–499.

Bächli H, Avoledo P, Gratzl O, Tolnay M. Therapeutic strategies and management of desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma: two case reports and literature overview. Childs Nerv Syst 2003 Jun;19(5–6):359–366.

Bader A, Heran M, Dunham C, Steinbok P. Radiological features of infantile glioblastoma and desmoplastic infantile tumors: British Columbia’s Children’s Hospital experience. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2015 Aug;16(2):119–125. doi: 10.3171/2014.10.PEDS13634.

Beppu T, Sato Y, Uesugi N, Kuzu Y, Ogasawara K, Ogawa A. Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma and characteristics of the accompanying cyst. Case Rep J Neurosurg Pediatr 2008 Feb;1(2):148–151. doi: 10.3171/PED/2008/1/2/148.

Bhardwaj M, Sharma A, Pal HK. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma with calcification. Neuropathology 2006 Aug;26(4):318–322.

Cerdá-Nicolás M, Lopez-Gines C, Gil-Benso R, Donat J, Fernandez-Delgado R, Pellin A, Lopez-Guerrero JA, Roldan P, Barbera J. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma. Morphological, immunohistochemical and genetic features. Histopathology 2006 Apr;48(5):617–621.

Darwish B, Arbuckle S, Kellie S, Besser M, Chaseling R. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma/astrocytoma with cerebrospinal metastasis. J Clin Neurosci 2007 May;14(5):498–501.

Duffner PK, Burger PC, Cohen ME, Sanford RA, Krischer JP, Elterman R, Aronin PA, Pullen J, Horowitz ME, Parent A, et al. Desmoplastic infantile gangliogliomas: an approach to therapy. Neurosurgery 1994 Apr;34(4):583–589; discussion 589.

Gessi M, Zur Mühlen A, Hammes J, Waha A, Denkhaus D, Pietsch T. Genome-wide DNA copy number analysis of desmoplastic infantile astrocytomas and desmoplastic infantile gangliogliomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2013 Sep;72(9):807–815. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182a033a0.

Gu S, Bao N, Yin MZ. Combined Fontanelle puncture and surgical operation in treatment of desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma: case report and a review of the literature. J Child Neurol 2010 Feb;25(2):216–221. doi: 10.1177/0883073809333542.

Hoving EW, Kros JM, Groninger E, den Dunnen WF. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma with a malignant course. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2008 Jan;1(1):95–98. doi: 10.3171/PED-08/01/095.

Jurkiewicz E, Grajkowska W, Nowak K, Kowalczyk P, Walecka A, Dembowska-Bagińska B. MR imaging, apparent diffusion coefficient and histopathological features of desmoplastic infantile tumors-own experience and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst 2015 Feb;31(2):251–259. doi: 10.1007/s00381-014-2593-2.

Knapp J, Olson L, Tye S, Bethard JR, Welsh CA, Rumbolt Z, Takacs I, Maria BL. Case of desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma secreting ceruloplasmin. J Child Neurol 2005 Nov;20(11):920–924.

Koelsche C, Sahm F, Paulus W, Mittelbronn M, Giangaspero F, Antonelli M, Meyer J, Lasitschka F, von Deimling A, Reuss D. BRAF V600E expression and distribution in desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma/ganglioglioma. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2014 Apr;40(3):337–344. doi: 10.1111/nan.12072.

Kuchelmeister K, Bergmann M, von Wild K, Hochreuther D, Busch G, Gullotta F (1993) Desmoplastic ganglioglioma: report of two non-infantile cases. Acta Neuropathol 85(2):199–204

Lababede O, Bardo D, Goske MJ, Prayson RA. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma (DIG): cranial ultrasound findings. Pediatr Radiol 2001 Jun;31(6):403–405.

Nikas I, Anagnostara A, Theophanopoulou M, Stefanaki K, Michail A, Hadjigeorgi Ch. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma: MRI and histological findings case report. Neuroradiology 2004 Dec;46(12):1039–1043.

Olas E, Kordek R, Biernat W, Liberski PP, Zakrzewski K, Alwasiak J, Polis L (1998) Desmoplastic cerebral astrocytoma of infancy: a case report. Folia Neuropathol 36(1):45–51

Phi JH, Koh EJ, Kim SK, Park SH, Cho BK, Wang KC. Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma: recurrence with malignant transformation into glioblastoma: a case report. Childs Nerv Syst 2011 Dec;27(12):2177–2181. doi: 10.1007/s00381-011-1587-6.

Rothman S, Sharon N, Shiffer J, Toren A, Pollak L, Mandel M, Kenet G, Neumann Y, Nass D (1997) Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma. Acta Oncol 36(6):655–657

Setty SN, Miller DC, Camras L, Charbel F, Schmidt ML. Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma with metastases at presentation. Mod Pathol 1997 Sep;10(9):945–951. Review.

Taguchi Y, Sakurai T, Takamori I, Sekino H, Tadokoro M. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma with extraparenchymatous cyst—case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1993 Mar;33(3):177–180.

Tamburrini G, Colosimo C Jr, Giangaspero F, Riccardi R, Di Rocco C. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma. Childs Nerv Syst 2003 Jun;19(5–6):292–297.

Taranath A, Lam A, Wong CK. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma: a questionably benign tumour. Australas Radiol 2005 Oct;49(5):433–437.

Taratuto AL, VandenBerg SR, Rorke LB (2000) Desmoplastic infantile astrocytoma and ganglioglioma. In: Kleihues P, Cavanee WK (eds) WHO classification of tumors, pathology and genetics: tumors of the central nervous system. ARC Press, Lyon, pp. 99–102

Taratuto AL, Monges J, Lylyk P, Leiguarda R. Superficial cerebral astrocytoma attached to dura. Report of six cases in infants. Cancer 1984 Dec 1;54(11):2505–2512.

Tenreiro-Picon OR, Kamath SV, Knorr JR, Ragland RL, Smith TW, Lau KY (1995) Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma: CT and MRI features. Pediatr Radiol 25(7):540–543

Trehan G, Bruge H, Vinchon M, Khalil C, Ruchoux MM, Dhellemmes P, Ares GS. MR imaging in the diagnosis of desmoplastic infantile tumor: retrospective study of six cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004 Jun-Jul;25(6):1028–1033.

VandenBerg SR. Desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma and desmoplastic cerebral astrocytoma of infancy. Brain Pathol 1993 Jul;3(3):275–281. Review.

VandenBerg SR, May EE, Rubinstein LJ, Herman MM, Perentes E, Vinores SA, Collins VP, Park TS. Desmoplastic supratentorial neuroepithelial tumors of infancy with divergent differentiation potential (“desmoplastic infantile gangliogliomas”). Report on 11 cases of a distinctive embryonal tumor with favorable prognosis. J Neurosurg 1987 Jan;66(1):58–71.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bianchi, F., Tamburrini, G., Massimi, L. et al. Supratentorial tumors typical of the infantile age: desmoplastic infantile ganglioglioma (DIG) and astrocytoma (DIA). A review. Childs Nerv Syst 32, 1833–1838 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-016-3149-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-016-3149-4