Abstract

Introduction

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (histiocytosis X) is a rare disorder that can manifest with solitary bony lesions or disseminated disease in various tissues. A common manifestation of the disease is diabetes insipidus even in the absence of neural involvement. Disseminated disease often involves the central nervous system, but only six isolated lesions in the infundibulum have been reported.

Case report

An 18-year-old male had failed to develop secondary sexual characteristics. He also had diabetes insipidus for more than 1 year. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed a 1-cm homogeneously enhancing mass in the region of the infundibulum. No other lesions were found in other organ systems. The patient underwent an orbitozygomatic osteotomy and pterional craniotomy. The lesion, which was adherent to the infundibulum, was partially resected. Microscopic analysis showed multiple lymphocytes and eosinophils with Langerhans cells that stained positive for S-100. Langerhans cell histiocytosis was diagnosed, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 6 with no neurological deficits. His diabetes insipidus persisted, and he underwent intensity-modulated radiation therapy to the sellar region.

Conclusions

Isolated Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the infundibulum is rare. The usual presentation is hypothalamic-pituitary axis dysfunction and diabetes insipidus. Patients with diabetes insipidus of unknown origin should undergo MRI of the sellar region to rule out infundibular abnormalities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a rare disorder that affects the reticuloendothelial tissue and can range from solitary bone lesions to widely disseminated disease. It typically affects children, and its incidence is estimated at 3–4 per million individuals per year [1]. Although disorders involving the hypothalamic-pituitary axis are commonly associated with Langerhans cell histiocytosis, lesions involving the hypothalamic-pituitary axis itself are relatively rare. Even more rare are solitary lesions in the infundibulum. Only six cases have been reported [2–6]. We report a case of an isolated Langerhans cell histiocytosis granuloma on the infundibulum that manifested as fulminant diabetes insipidus.

Case report

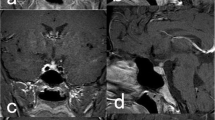

An 18-year-old Native American man sought treatment after failing to develop secondary sexual characteristics or to grow. In the previous year, he also had developed gradually progressive diabetes insipidus. He reached medical attention because he lived in a house on a reservation without running water and needed to travel to the nearest town daily to obtain enough drinking water to satisfy his exaggerated thirst. A magnetic resonance image (MRI) showed a solitary lesion on the infundibulum that enhanced with the administration of gadolinium (Fig. 1). No other abnormalities were discovered upon physical examination except mild hypogonadia.

Further diagnostic evaluation included a lumbar puncture. His cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was normal, as were his levels of alpha fetal protein and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin. An endocrinologic evaluation showed decreased levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone, cortisol, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and vasopressin. He was referred for diagnostic biopsy and underwent an orbitozygomatic-pterional craniotomy. The intraoperative pathological diagnosis was consistent with Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and a subtotal resection was performed to preserve the infundibulum. His postoperative course was uneventful, and he was discharged home on postoperative day 6. His diabetes insipidus continued to be symptomatic, but he was able to self-regulate his water intake in compensation.

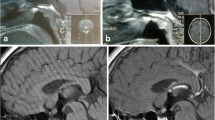

The biopsy specimen showed the typical inflammatory infiltration with diffuse Langerhans cells (Fig. 2). The specimen stained positive for S-100 (Fig. 3), which is also consistent with Langerhans cell histiocytosis [7]. He underwent intensity-modulated radiation therapy to a region of the infundibulum for local control of his disease 6 weeks after surgery. The radiation dosage was 2,100 cGy administered in 15 fractions [8]. At 2 years following his procedure, he was still symptomatic with diabetes insipidus, which was treated with a daily desmopressin dose via a nasal spray. He was also on thyroid hormone replacement therapy, and he was also on insulin for diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

Langerhans cell histiocytosis was originally known as Gagel’s granuloma, in reference to the author who first reported the condition in 1941 [9]. In that early case, however, the lesion encompassed the hypothalamus, infundibulum, and neurohypophysis rather than the infundibulum alone, as in our patient. The term has now been replaced to conform to the currently accepted classification of histiocytoses.

Based on the currently recommended classification system, Langerhans cell histiocytosis is also known as a class I histiocytosis [1] The other three classes of these disorders encompass lesions that do not originate from Langerhans cells and have an infectious origin or are highly malignant. Langerhans cell histiocytosis is the most common of the histiocytoses. Its peak incidence is in infants 1–2 years old, but individuals of all ages can be afflicted. Although Langerhans cell histiocytosis is the most common of this class of diseases, it is still extremely rare. Its incidence is only 3–4 per million individuals per year in children younger than 15 years old. Males are affected twice as often as females, and almost all cases are sporadic.

The pathogenesis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis is still under investigation. Langerhans cells are produced by hemopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow and normally migrate to the skin. They are important in cell-mediated immune responses and are powerful antigen-presenting cells. The pathophysiology of Langerhans cell histiocytosis is thought to involve either an inherently dysfunctional population of Langerhans cells or abnormal T cells secreting cytokines, which attract normal Langerhans cells and lead to tissue destruction [10]. However, no studies have yet identified the underlying mechanism.

The central nervous system is involved in Langerhans cell histiocytosis in as many as 25% of the cases associated with widespread dissemination [11]. It usually manifests as osseous infiltration from calvarial lesions, but focal lesions can occur anywhere within the brain parenchyma or meninges.

Diabetes insipidus is a common symptom of Langerhans cell histiocytosis; its incidence approaches 25% of the patients with multisystem disease [1]. Diabetes insipidus is often caused by compression of the infundibulum by adjacent osseous lesions [11]. The rare exception is direct compression from focal suprasellar lesions.

Because the aggressiveness of Langerhans cell histiocytosis in systemic disease varies, its treatment is controversial. Simple observation is a reasonable option in symptomatic patients. Spontaneous resolution is relatively common [1]. Symptomatic patients have been treated with several regimens, including steroids, cytotoxic agents, and low-dose radiation. In these patients, treatment of diabetes insipidus primarily consists of hormonal replacement, vasopressin, and radiation to the infundibulum. Radiation therapy has been moderately beneficial as a treatment for diabetes insipidus. The best responses (60% resolution) have occurred in patients treated with more than 1,500 cGy [8]. The role for surgery is limited to diagnostic purposes and the rare, rapidly progressing lesion that compresses neuronal structures (e.g., optic apparatus).

References

Broadbent V, Pritchard J (1996) The histiocytoses. In: Weatherall DJ, Ledingham JGG, Warrell DA (eds) Oxford textbook of medicine. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 3606–3610

Beers GJ, Manson J, Carter AP, Bell R (1986) Intracranial histiocytosis X: a case report. J Comput Tomogr 10:237–241

O’Sullivan RM, Sheehan M, Poskitt KJ, Graeb DA, Chu AC, Joplin GF (1991) Langerhans cell histiocytosis of hypothalamus and optic chiasm: CT and MR studies. J Comput Assist Tomogr 15:52–55

Scholz M, Firsching R, Feiden W, Breining H, Brechtelsbauer D, Harders A (1995) Gagel’s granuloma (localized Langerhans cell histiocytosis) in the pituitary stalk. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 97:164–166

Asano T, Goto Y, Kida S, Ohno K, Hirakawa K (1999) Isolated histiocytosis X of the pituitary stalk. J Neuroradiol 26:277–280

Isoo A, Ueki K, Ishida T, Yoshikawa T, Fujimaki T, Suzuki I, Sasaki T, Kirino T (2000) Langerhans cell histiocytosis limited to the pituitary-hypothalamic axis—two case reports. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 40:532–535

Takahashi K, Isobe T, Ohtsuki Y, Akagi T, Sonobe H, Okuyama T (1984) Immunohistochemical study on the distribution of alpha and beta subunits of S-100 protein in human neoplasm and normal tissues. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol 45:385–396

Minehan KJ, Chen MG, Zimmerman D, Su JQ, Colby TV, Shaw EG (1992) Radiation therapy for diabetes insipidus caused by Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 23:519–524

Gagel O (1941) Granulationsgeschwulst im Gebiet des Hypothalamus. Z Neurol 172:710–722

Osband ME, Pochedly C (1987) Histiocytosis-X: an overview. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 1:1–7

Horvath E, Scheithauer BW, Kovacs K, Lloyd RV (1997) Regional neuropathology: hypothalamus and pituitary. In: Graham DI, Lantos PL (eds) Greenfield’s neuropathology. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 1007–1087

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Horn, E.M., Coons, S.W., Spetzler, R.F. et al. Isolated Langerhans cell histiocytosis of the infundibulum presenting with fulminant diabetes insipidus. Childs Nerv Syst 22, 542–544 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-005-0022-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-005-0022-2