Abstract

Predictors of early and late failure of pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis (CP) have not been established. Early and late outcomes of a cumulative series of 81 (mean age 60 years; mean EuroSCORE II, 3.3%) consecutive patients from three European cardiac surgery centers were reviewed. Predictors of a combined endpoint comprising in-hospital death or major complications (including multiple transfusion) were identified with binary logistic regression. Non-parametric estimates of survival were obtained with the Kaplan–Meier method. Predictors of poor late outcomes were established using Cox proportional hazard regression. There were 4 (4.9%) in-hospital deaths. Preoperative central venous pressure > 15 mmHg (p = 0.005) and the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (p = 0.016) were independent predictors of complicated in-hospital course, which occurred in 29 (35.8%) patients. During follow-up (median, 5.4 years), preoperative renal impairment was a predictor of all-cause death (p = 0.0041), cardiac death (p = 0.0008), as well as hospital readmission due to congestive heart failure (p = 0.0037); while partial pericardiectomy predicted all-cause death (p = 0.028) and concomitant cardiac operation predicted cardiac death (p = 0.026), postoperative central venous pressure < 10 mmHg was associated with a low risk both of all-cause and cardiac death (p < 0.0001 for both). Ten-year adjusted survival free of all-cause death, cardiac death, and hospital readmission were 76.9%, 94.7%, and 90.6%, respectively. In high-risk patients with CP, performing pericardiectomy before severe constriction develops and avoiding cardiopulmonary bypass (when possible) could contribute to improving immediate outcomes post-surgery. Complete removal of cardiac constriction could enhance long-term outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Constrictive pericarditis (CP) is an inflammatory disease of the pericardial leaflets that results in pericardial thickening and fibrosis. These irreversible changes of the pericardium ultimately lead to impairment of right heart filling [1,2,3,4]. While, in Africa [5] and India [6], tuberculosis is the prevalent etiology, the underlying cause of CP is unknown in most patients in Europe [7,8,9,10,11,12], North America [13,14,15,16], China [17], and Japan [18], although many of these patients may have suffered from prior, unrecognized viral pericarditis. In the last 2 decades, the previous cardiac operations and radiation treatments of the chest [8, 9, 14, 16, 18, 19], as well as autoimmune or immune-modulated diseases, have become increasingly common causes of CP [1, 2], although tuberculosis remains a frequent etiology in the present era of population migration.

Surgical therapy of CP is indicated for all patients with worsening dyspnea and asthenia, specific symptoms of right ventricular diastolic dysfunction, such as swelling of the jugular veins, edema of legs and feet, hepatomegaly, and ascites, as well as palpitations, oliguria, and low cardiac output [1, 2]. Complete pericardiectomy through full sternotomy is the treatment of choice to remove constriction in these patients. Yet, the predictors of early and late failure of pericardiectomy for CP have not been established. The aim of the present study was to review pooled results from three series of pericardiectomies to identify independent predictors of complicated in-hospital course, and of long-term all-cause and cardiac mortality.

Patients and methods

Study patients

The study population consisted of a cumulative series of consecutive subjects who underwent pericardiectomy for CP at one of three European cardiac surgery units: (1) the Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery of the University Hospital Jean-Minjoz of Besançon, France (period of surgery, 1986–2017); (2) the Department of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery of the University Hospital Henry-Mondor, Créteil, Paris, France (period of surgery, 2008–2019); and (3) the Cardio-Thoracic and Vascular Department of the University Hospital of Trieste, Italy (period of surgery, 2001–2018).

Baseline characteristics of patients, causes of CP, operative data, and relevant details pertaining to the hospital course of patients were retrospectively collected from patient files. For every patient, the diagnosis of CP was first suspected based on the symptoms of pericardial constriction, and subsequently confirmed by echocardiographic assessment and right heart catheterization.

Definitions

Unless otherwise stated, the definitions of preoperative variables were those used for the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II (EuroSCORE II). The risk profile of each patient was established preoperatively according to EuroSCORE II [20]. We used internationally agreed definitions of complications after cardiac surgery, as validated and published in the literature [21]. The patient’s in-hospital course was defined as complicated when death or any one or more of the following major complications occurred: low cardiac output, acute kidney injury, prolonged (> 48 h) mechanical ventilation, need for three or more transfused packed red blood cells (RBCs), mediastinal re-entry for bleeding or tamponade, mediastinitis, multiorgan failure, or sepsis.

Surgical technique

Patients with complete pericardiectomy via median sternotomy were considered. This included removal of the whole anterior pericardium (phrenic nerve-to-phrenic nerve), the diaphragmatic pericardium, and, when accessible, a portion of pericardium posterior to the left phrenic nerve. When complete pericardiectomy was not technically feasible, and a minor portion of pericardium was removed, the procedure defined as incomplete or partial pericardiectomy. Partial pericardiectomy was sometimes performed via right or left thoracotomy. Cardiopulmonary bypass was performed in case of severe constriction or when concomitant cardiac procedures were scheduled. It was also used to ensure completeness of pericardiectomy, primarily in the presence of deep calcifications involving the myocardium.

Follow-up

Clinical follow-up was obtained by the following sequential procedure: telephone contact with the patient, or the patient’s family; if they could not be contacted, telephone contact with the general practitioner, referring cardiologist or other specialists listed in the patient’s medical file; finally, consultation of the national death registry or the town halls of the place of birth to obtain data regarding the vital status (dead or alive at the cut-off date). Information on long-term survival of patients, cause of death (where applicable), as well as data regarding hospital readmission due to congestive heart failure (CHF) during the follow-up period were recorded. Readmission data were obtained from the hospital medical informatics system and patients’ medical files. The cut-off date for collecting data was fixed at March 1st, 2019.

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval to conduct the study, as well as to contact the patients and their families, was obtained from the local ethics committee of each participating center, based on retrospective data retrieval; the need for individual written consent was waived.

Statistical methods

Categorical variables are presented as numbers (percentages) and quantitative variables as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical comparisons of perioperative variables were performed using the Chi-square or Student’s t test as appropriate. Backward stepwise logistic regression was used to identify independent predictors of complicated in-hospital course. All variables with a p value < 0.1 by univariable analysis were included in the multivariable model. For each variable, the odds ratio (OR) and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated. Goodness-of-fit (calibration) and accuracy of prediction (discriminatory power) of the model were evaluated with the Hosmer–Lemeshow test and receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, respectively. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to identify independent predictors of all-cause death, cardiac death, and hospital readmission due to CHF during the follow-up period. For each variable, the proportional hazards assumption was verified with the Schoenfeld residual test. The hemodynamic parameters were dichotomized according to internationally validated cut-offs [18, 20, 21], or according to ROC curve analysis and the Youden index. Non-parametric estimates and curves for freedom from all-cause death, cardiac death, and hospital readmission due to CHF during the follow-up period were prepared using the Kaplan–Meier method, and adjusted for the following known confounders: age, extracardiac arteriopathy, glomerular filtration rate as estimated by the Cockcroft–Gault formula, left ventricular ejection fraction, partial pericardiectomy, concomitant cardiac operation, and postoperative CVP < 10 mmHg. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Data analysis was performed using the SPSS software for Windows, version 13.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

A total of 81 patients (mean age 60 ± 11.9 years; males 72.8%; mean EuroSCORE II, 3.3% ± 3.9%) were included in the study. Relevant comorbidities such as anemia, chronic lung disease, extracardiac arteriopathy, severe renal impairment, morbid obesity, hypertension, and diabetes were present in 46.9%, 13.6%, 18.5%, 16%, 24.7%, 58%, and 32.1% of cases, respectively. There were severe symptoms of congestive heart failure in 49 (60.5%) patients. Preoperative central venous pressure (CVP) > 15 mmHg and cardiac index < 2.0 l/min/m2 occurred in 35.8% and 18.5% of cases, respectively. Sixteen (19.8%) patients had had prior cardiac operation. The underlying cause of CP was unknown in about 40% of patients; post-cardiac surgery constriction and tuberculosis were other frequent etiologies. Pericardiectomy was performed on a non-elective surgical priority in 28.4% of cases, was partial in 27.2%, required cardiopulmonary bypass in 25.9%, and was associated with the other cardiac surgical procedures in 21% of cases (Tables 1, 2, 3).

In-hospital outcomes

There were 4 (4.9%) in-hospital deaths; low cardiac output, acute kidney injury, multiorgan failure, and sepsis were the corresponding causes. Multiple transfusion (transfusion of three or more RBCs), acute kidney injury, low cardiac output, prolonged (> 48 h) mechanical ventilation, and multiorgan failure were frequent major postoperative complications. Overall, 29 (35.8%) patients had a complicated in-hospital course (Table 4). Recruiting site 2 (Suppl. Text), preoperative anemia, prior coronary surgery, post-cardiac surgery constriction as CP etiology, preoperative CVP > 15 mmHg, and the use of cardiopulmonary bypass were risk factors for complicated in-hospital course by univariable analysis (Tables 1, 2, 3). Recruiting site 2 (OR 9.78, p value 0.002), preoperative anemia (OR 8.65, p value 0.006) and CVP > 15 mmHg (OR, 8.25, p value 0.005), as well as on-pump technique (OR 6.14, p value 0.016) were found to be predictors of complicated in-hospital course following pericardiectomy by multivariable analysis (Table 5 and Suppl. Table S5).

Late outcomes

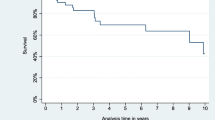

During the follow-up period (median 5.4 years, interquartile range 2.3–10.2 years), there were 22 deaths (9 cardiac) and 10 hospital readmissions due to CHF; two patients underwent redo surgery for recurrent CP. By Cox proportional hazards analysis, preoperative renal impairment was a predictor of all-cause death (p = 0.0041), cardiac death (p = 0.0008), and hospital readmission for CHF (p = 0.0037); partial pericardiectomy was predictor of all-cause death (p = 0.028); concomitant cardiac operation was predictor of cardiac death (p = 0.026); postoperative CVP < 10 mmHg was associated with a low risk both of all-cause and cardiac death (p < 0.0001 for both) (Table 6 and Suppl. Table S6). The 10-year non-parametric estimates of survival free of all-cause death, cardiac death, and hospital readmission due to CHF were 66.1% (95% CI 59–73.2%), 83.5% (95% CI 77.8–89.2%), and 80.4% (95% CI 73.6–87.2%), respectively. The 10-year adjusted survival free of all-cause death, cardiac death, and hospital readmission due to CHF were 76.9%, 94.7%, and 90.6%, respectively (Figs. 1, 2, 3).

Discussion

This retrospective study explored outcomes of patients after pericardiectomy for CP from three European cardiac surgery centers, and found that there is a persisting risk of in-hospital adverse events and mortality with this procedure. In-hospital mortality post-surgery was 4.9% (ranging from 3.6 to 6.9% in the three centers) and was higher (albeit non-significantly) than the mean expected operative risk by EuroSCORE II (3.3%). Thirty-six percent of patients (range 13.8–64.3% across the three centers) suffered at least one major complication after surgery, most frequently multiple blood transfusion, acute kidney injury, low cardiac output, prolonged mechanical ventilation, and multiorgan failure. However, this was not an unexpected finding. Although there have been significant improvements throughout the years, as confirmed in an excellent analysis performed at the Mayo Clinic by Murashita et al. [16], where the 30-day mortality decreased significantly from 13.5% (35 of 259 patients), in the historical era (pre-1990), to 5.2% (42 of 807) in the contemporary era (1990–2013), recent contributions in the literature [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] have reported perioperative mortality rates after pericardiectomy for CP in western countries ranging from 2.1% (1 of 47) [11] to 18.6% (18 of 97) [9]. According to these studies, while surgery within 6 months after onset of symptoms seems to reduce the risk of early death [13], comorbidities such as renal impairment [15] and hepatomegaly [13], preoperative right and left ventricular dilatation/dysfunction [9, 15], as well as concomitant heart valve surgery [13] and the need for cardiopulmonary bypass [10, 14, 22] all seem to be associated with an increased risk of early death post-surgery. These conclusions are in line with the findings of the present study where high values of CVP due to a chronic inflammatory disease producing heart constriction gradually, as well as the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (for the presence of severe constriction or when concomitant cardiac procedures were carried out) were found to be independent predictors of the patients’ complicated in-hospital course. In addition, since multiple blood transfusion was included in the definition of in-hospital complications, it is unsurprising that preoperative anemia should be an independent predictor of complicated outcome early after surgery. However, as the introduction of anemia in the multivariable model for the outcome of interest (complicated in-hospital course) could have skewed the results, a second analysis without including anemia was performed, the yielded similar results. Actually, comorbidities other than anemia, severity and duration of symptoms, etiology of pericarditis, left ventricular dysfunction, preoperative shock or hypotension, pulmonary hypertension, as well as partial pericardiectomy were not ultimately found to be independent risk factors for poor outcome of pericardiectomy by multivariable analysis.

As regards late outcomes, based on the results of the present analysis, pericardiectomy appears to be relatively successful in resolving cardiac constriction. Indeed, only two patients underwent repeat surgery for recurrent CP during a median follow-up of over 5 years. Preoperative renal impairment was a predictor of all-cause death, cardiac death, and hospital readmission for CHF; partial pericardiectomy was predictor of all-cause death; concomitant cardiac operation was predictor of cardiac death; finally, postoperative CVP < 10 mmHg was associated with a low risk both of all-cause and cardiac death. These results are in agreement with more recent reports where older age [7, 18], chronic lung disease and preoperative renal impairment [9, 13], preoperative New York Heart Association functional class III–IV [7, 8, 16, 18], atrial fibrillation [18], concomitant coronary artery disease [9], etiologies of CP such as post-cardiac surgery constriction [8, 14, 16, 18], post-chest radiation [14, 16] and malignancy [11], postoperative right atrial pressure ≥ 9 mmHg [18], and partial pericardiectomy [11, 12, 17] were associated with increased mortality and decreased functional improvement at follow-up. In the presence of severe constriction, radical surgery, consisting in removing as much fibrotic tissue as possible both in extension and depth, is a very challenging operation in the case of epicarditis. For these patients, some authors have devised a technique involving multiple longitudinal and transverse incisions of the epicardium [23, 24]. Although the use of cardiopulmonary bypass was associated with poorer immediate outcomes in the present experience, this finding likely reflects the need for extended resection because of more extensive disease (or the presence of concomitant heart diseases in need of surgery) rather than the impact of known physiologic sequelae of extracorporeal circulation. While the use of the on-pump technique may make it possible to achieve more complete resection, we strongly believe that the benefits of using cardiopulmonary bypass far outweigh the theoretical risks. Finally, the 10-year adjusted survival of patients in the present study was comparable (76.9% vs. 81%) [11] or even compared favorably (76.9% vs. 49.2%) [14] with the few literature reports to date that have explored long-term outcomes after pericardiectomy. This better result could be due to the lower rate of post-cardiac surgery constriction as the etiology of CP (17.3% vs. 30.6%) [14].

This study suffers from some limitations that deserve to be underlined. The retrospective nature of the study, and the fact that it was performed on a limited number of patients operated on in three different centres could have affected significantly the results. A further limitation is that we included patients that were operated on during a period spanning over 20 years. Although we chose this period to assemble as many patients as possible, we are aware that changes in surgical technique, or the medical and pharmacological environment, or differences in practices between centres during this period could have had a confounding effect. Nonetheless, no significant differences were found between centres in terms of the late results. Besides, the surgical technique for pericardiectomy did not change significantly during that time. Finally, the multivariable analyses of the present study may be underpowered because of the small number of events. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution, and warrant further confirmation in studies with a larger sample size.

Conclusions

Although pericardiectomy is recognized as a surgical technique that provides significant improvement in survival and functional status of patients with constrictive pericarditis, both mortality and morbidity post-surgery remain high. Performing surgery before severe impairment of the right heart filling develops, and avoiding cardiopulmonary bypass during isolated pericardiectomy could improve immediate outcomes. Complete removal of cardiac constriction should enhance long-term outcomes.

References

Welch TD (2018) Constrictive pericarditis: diagnosis, management and clinical outcomes. Heart 104:725–731

Welch TD, Oh JK (2017) Constrictive pericarditis. Cardiol Clin 35:539–549

Madeira M, Teixeira R, Costa M, Gonçalves L, Klein AL (2016) Two-dimensional speckle tracking cardiac mechanics and constrictive pericarditis: systematic review. Echocardiography 33:1589–1599

Garcia MJ (2016) Constrictive pericarditis versus restrictive cardiomyopathy? J Am Coll Cardiol 67:2061–2076

Yangni-Angate KH, Tanauh Y, Meneas C, Diby F, Adoubi A, Diomande M (2016) Surgical experience on chronic constrictive pericarditis in African setting: review of 35 years' experience in Cote d'Ivoire. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 6:S13–S19

Kumawat M, Lahiri TK, Agarwal D (2018) Constrictive pericarditis: retrospective study of 109 patients. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 26:347–352

Porta-Sánchez A, Sagristà-Sauleda J, Ferreira-González I, Torrents-Fernández A, Roca-Luque I, García-Dorado D (2015) constrictive pericarditis: etiologic spectrum, patterns of clinical presentation, prognostic factors, and long-term follow-up. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 68:1092–1100

Szabó G, Schmack B, Bulut C, Soós P, Weymann A, Stadtfeld S, Karck M (2013) Constrictive pericarditis: risks, aetiologies and outcomes after total pericardiectomy: 24 years of experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 44:1023–1028

Busch C, Penov K, Amorim PA, Garbade J, Davierwala P, Schuler GC, Rastan AJ, Mohr FW (2015) Risk factors for mortality after pericardiectomy for chronic constrictive pericarditis in a large single-centre cohort. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 48:e110–e116

Rupprecht L, Putz C, Flörchinger B, Zausig Y, Camboni D, Unsöld B, Schmid C (2018) Pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis: an institution's 21 years experience. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 66:645–650

Biçer M, Özdemir B, Kan İ, Yüksel A, Tok M, Şenkaya I (2015) Long-term outcomes of pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis. J Cardiothorac Surg 10:177

Nozohoor S, Johansson M, Koul B, Cunha-Goncalves D (2018) Radical pericardiectomy for chronic constrictive pericarditis. J Card Surg 33:301–307

Vistarini N, Chen C, Mazine A, Bouchard D, Hebert Y, Carrier M, Cartier R, Demers P, Pellerin M, Perrault LP (2015) Pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis: 20 years of experience at the Montreal Heart Institute. Ann Thorac Surg 100:107–113

George TJ, Arnaoutakis GJ, Beaty CA, Kilic A, Baumgartner WA, Conte JV (2012) Contemporary etiologies, risk factors, and outcomes after pericardiectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 94:445–451

Gillaspie EA, Stulak JM, Daly RC, Greason KL, Joyce LD, Oh J, Schaff HV, Dearani JA (2016) A 20-year experience with isolated pericardiectomy: analysis of indications and outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 152:448–458

Murashita T, Schaff HV, Daly RC, Oh JK, Dearani JA, Stulak JM, King KS, Greason KL (2017) Experience with pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis over eight decades. Ann Thorac Surg 104:742–750

Zhu P, Mai M, Wu R, Lu C, Fan R, Zheng S (2015) Pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis: single-center experience in China. J Cardiothorac Surg 10:34

Nishimura S, Izumi C, Amano M, Imamura S, Onishi N, Tamaki Y, Enomoto S, Miyake M, Tamura T, Kondo H, Kaitani K, Yamanaka K, Nakagawa Y (2017) Long-term clinical outcomes and prognostic factors after pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis in a Japanese population. Circ J 81:206–212

Gillaspie EA, Dearani JA, Daly RC, Greason KL, Joyce LD, Oh J, Schaff HV, Stulak JM (2017) Pericardiectomy after previous bypass grafting: analyzing risk and effectiveness in this rare clinical entity. Ann Thorac Surg 103:1429–1433

Nashef SA, Roques F, Sharples LD, Nilsson J, Smith C, Goldstone AR, Lockowandt U (2012) EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 41:734–744

Biancari F, Ruggieri VG, Perrotti A, Svenarud P, Dalén M, Onorati F, Faggian G, Santarpino G, Maselli D, Dominici C, Nardella S, Musumeci F, Gherli R, Mariscalco G, Masala N, Rubino AS, Mignosa C, De Feo M, Della Corte A, Bancone C, Chocron S, Gatti G, Gherli T, Kinnunen EM, Juvonen T (2015) European Multicenter Study on Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (E-CABG registry): study protocol for a prospective clinical registry and proposal of classification of postoperative complications. J Cardiothorac Surg 10:90

Rupprecht L, Schmid C (2018) More reasons for pericardiectomy without cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg 105:1280

Heimbecker RO, Smith D, Shimizu S, Kestle J (1983) Surgical technique for the management of constrictive epicarditis complicating constrictive pericarditis (the waffle procedure). Ann Thorac Surg 36:605–606

Faggian G, Mazzucco A, Tursi V, Bortolotti U, Gallucci V (1990) Constrictive epicarditis after open heart surgery: the turtle cage operation. J Card Surg 5:318–320

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gatti, G., Fiore, A., Ternacle, J. et al. Pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis: a risk factor analysis for early and late failure. Heart Vessels 35, 92–103 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-019-01464-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-019-01464-4