Abstract

Purpose

To investigate whether patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma benefit from sequential therapies with the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) sorafenib and sunitinib.

Patients and methods

A total of 89 patients were treated in nine German centres between 2002 and 2009. The TKI sequence started as first-, second- or third-line therapy after prior chemo- or immunotherapy. When progression was diagnosed, treatment was switched to the second TKI until further progression.

Results

Overall progression-free survival (PFS) of patients receiving sunitinib followed by sorafenib shows no statistically significant difference to patients receiving sorafenib followed by sunitinib (15.4 months vs. 12.1 months). The secondary use of sorafenib resulted in a median PFS of 3.8 months if the TKI sequence had been started as a first-line treatment and of 3.5 months if the TKI sequence had been started second-line treatment. The secondary use of sunitinib resulted in a median PFS of 3.4 and 4.0 months, respectively. OS was 28.8 months for all patients, without a statistically significant difference between the two groups.

Conclusions

This study endorses the notion of a clinical benefit of the sequential use of sorafenib and sunitinib and supports observations from previous studies. In terms of the optimal succession of the two TKIs, the study does not allow a definite answer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The tyrosine kinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib were the first-targeted drugs to be launched for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) in 2006. Their introduction has improved the prognosis for mRCC patients under palliative therapy considerably. In large clinical trials, their efficacy has been established both in a first-line and in a second-line setting [1, 2]. Both inhibitors are attacking similar targets and signal transduction pathways essential for the tumour’s angiogenesis and proliferation. Initially, it was therefore suspected that a cross-resistance between them might rule out the chances of their sequential use. In the meantime, however, the results of several studies suggest that no absolute cross-resistance exists. Hence, a sequential therapy with both inhibitors is increasingly regarded as an effective means of achieving a longer tumour control [3–7]. This fact could have its basis in the not completely overlapping target structures, for e.g. sorafenib additionally inhibits also Raf and the MEK/ERK pathway compared to sunitinib. To further explore this evidence that is still based on relatively few data, we investigated the therapeutic effects of sequences with both inhibitors on patients with mRCC in a retrospective, long-term, multi-centre study.

Patients and methods

Patient selection and treatment modalities

We performed a retrospective database and chart search in 4 urological hospitals and 5 medical practices specializing in oncology in Germany and identified 54 and 33 patients, respectively, who were treated with sequences of sunitinib followed by sorafenib or vice versa between 2002 and 2009. Two patients could not be assigned to a specific sequence because they switched therapies several times. The TKI sequence started as the first palliative therapy in treatment-naïve patients or as the second or third palliative therapy after pre-treatment with chemotherapy or immunomodulation. Patients pre-treated with mTOR inhibitors or VEGF antibodies (e.g. bevacizumab) were not eligible. No pre-selection took place with regard to specific physical examinations, treatment of drug-related adverse effects, complications, comorbidities or other patient characteristics.

Data from the first and second therapy line were recorded for all patients. Data from the third and fourth therapy line, respectively, were available for 47 and 18 patients. The most frequent first-line therapy was interferon-α in 44.9% of patients, followed by sunitinib (39.3%), interleukin-2 (37.1%) and 5-fluorouracil (31.5%). These numbers include first-line combinations of chemo- and immunotherapy. The most frequent second-line treatment was sorafenib (58.4%), followed by sunitinib (34.8%) (Table 1).

Standard doses of both sorafenib and sunitinib were used. Sorafenib was administered continuously, sunitinib in a 4 weeks on/2 weeks off-scheme in the majority of patients. Dose modifications became necessary in almost half of the patients, mostly caused by treatment-related toxicities. All possible dose modifications were made allowance for.

Radiologic evaluation took place in each therapy line by means of CT scans of the abdomen, pelvis and thorax. Tumour anamnesis, prognostic factors and treatment duration were recorded. Tumour response was measured according to clinical investigators’ assessment.

Once a progression was diagnosed or, in few cases, intolerability occurred, treatment was switched to the second TKI and continued until progression.

Statistics

The statistical analysis is primarily descriptive. Continuous criteria were characterized by the number of observations, mean value, median, minimum, standard deviation and/or confidence interval, categorical criteria by absolute or relative frequencies.

Progression-free survival and overall survival time were calculated using Kaplan–Meier analysis.

To compare progression-free survival times between both sequences, the log-rank test was applied. Further comparisons are of purely explorative nature and follow the usual statistical methods.

Patient characteristics and disease status prior to therapy

The median patient’s age was 64 years; male to female ratio was 3, and 92.1% had undergone a prior tumour nephrectomy. A clear-cell histology had been diagnosed in 71.9%, papillary in 5.6%, chromophob in 1.1% and other missing in 20.2% of patients.

Of the 87 patients who were eligible for the final analysis, 47 (54%) had been treatment-naïve. The sunitinib–sorafenib group had a higher ratio of treatment-naïve patients than the sorafenib–sunitinib group (61.1% vs. 42.4%). Of the patients, 12.1% in the sorafenib–sunitinib group and 9.3% in the sunitinib–sorafenib group began sequential therapy with a Karnofsky index <80%. Brain metastases were prevalent in 5.6% of patients.

Results

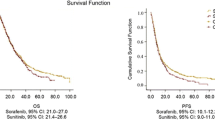

Median overall PFS, defined as the time from administration of the first TKI to disease progression or death under therapy with the second TKI, was 15.1 months. In patients treated with a sequence of sunitinib followed by sorafenib median, overall PFS shows no statistically significant difference to patients who received a sequence of sorafenib followed by sunitinib (15.4 months vs. 12.1 months; P = 0.5509). There was no significant difference in median overall PFS between patients ≤70 years and patients ≥70 years (15.1 months vs. 14.2 months; P = 0.6930). Median overall PFS of the TKI sequence was longer when this sequence had started as a second-line therapy than in treatment-naïve patients (13.4 months vs. 11.4 months in the sor-sun-group and 16.9 months vs. 15.3 months in the sun-sor-group). A first-line cytokine therapy did not preclude a significant clinical benefit, neither in the sor-sun- nor in the sun-sor-group.

PFS was also determined for single therapy lines and analysed subject to the start of the TKI sequence.

If the TKI sequence began in the first therapy line, median PFS for patients starting with sorafenib was 9.3 months and for patients starting with sunitinib 9.8 months in this first therapy line (P = 0.5096) (Fig. 1a). In these patients, second-line therapy with the second TKI resulted in an additional PFS of 3.4 months in the sor-sun-group and 3.8 months in the sun-sor-group (P = 0.6640) (Fig. 1b).

Kaplan–Meier analysis: a PFS in first-line therapy by sequence (first use of TKI in first treatment line), b PFS in second-line therapy (second part of TKI sequential therapy when started in first treatment line), c overall OS in months by sequence. a Sequence 1: sorafenib → sunitinib (n = 13), sequence 2: sorafenib → sunitinib (n = 29), b sequence 1: sorafenib → sunitinib (n = 12), sequence 2: sorafenib → sunitinib (n = 29), c sequence 1: sorafenib → sunitinib (n = 30), sequence 2: sorafenib → sunitinib (n = 50)

If the TKI sequence started as a second-line treatment, median PFS for patients starting with sorafenib was 4.9 months and for patients starting with sunitinib 9.8 months in this second therapy line (P = 0.1573). In these patients, third-line therapy with the second TKI yielded an additional PFS of 4.0 months in the sor-sun-group and 3.5 months in the sun-sor-group (P = 0.6006).

With regard to all patients included in our study, an objective response (CR or PR) was observed in the first therapy line in 23.6% of patients and in 9.0, 10.6 and 5.6%, respectively, in the subsequent therapy lines. Best response (CR or PR) in the sor-sun-group was 21.4% in first- and 17.6% in second-line treatment. Best response rates (CR or PR) in the sun-sor-group were 27.3% in first line and 17.6% in second line.

Overall survival (OS) time did not significantly differ between patients in both groups. Median OS was calculated as 28.8 months for all patients. In the sor-sun-group, it accounted for 28.8 months and in the sun-sor-group for 28.9 months (P = 0.7701) (Fig. 1c). Median OS in patients who started a TKI sequence treatment as their first-line therapy is not statistically different between the groups (22.5 months for sun-sor vs. 16.1 months for sor-sun; P = 0.7977). Median OS in pre-treated patients was 34.2 months in the sun-sor-group compared to 30.5 months for the reverse sequence (P = 0.8114).

At the time of the final study analysis, 44 of 89 patients had died, 35 were still alive and 10 were lost to follow-up.

Discussion

In recent years, the introduction of meanwhile six targeted drugs for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma has altered the medical management of this type of cancer fundamentally. Once an untreatable disease in more than 80% of patients, mRCC has now become accessible to a safe and effective palliative treatment in the majority of patients, both improving their survival and quality of life [8].

Among the three tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), two mTOR inhibitors and one antibody (in combination with interferon-α) that form the arsenal of targeted therapies for mRCC, sorafenib and sunitinib have been introduced first. Clinical experience with these two TKIs therefore exceeds that with their successors.

Beyond the phase III trials that lead to their approval, their safety and effectiveness have been proven in large expanded access programs. With the inclusion of relatively unselected patient populations, these open-label programs mirror a real-life setting as encountered in daily oncological practice [9–11].

Both sorafenib—initially discovered as a Raf kinase inhibitor—and sunitinib—also active against Ret kinase—are targeting the same vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs) and tyrosine kinases Flt-3 and c-Kit that are controlling tumour angiogenesis. They differ, e.g. in their inhibition of the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGFR) where sorafenib blocks PDGFR-α and sunitinib both PDGRF-α and -β.

Due to this wide overlap in their targets, a cross-resistance between both TKIs was assumed initially. First evidence to disprove this assumption was published by Tamaskar et al. [3] in a two-armed, single-centre study with 30 patients. They retrospectively demonstrated efficacy of the second-line application of either sorafenib or sunitinib after failure of first-line antiangiogenic treatment with a variety of drugs including sunitinib or sorafenib. Similar results showing a longer delay in disease progression and a much better tumour control in patients treated with a sequential TKI therapy were gained in a single-arm study by Eichelberg et al. [4] and in two two-arm studies by Dudek et al. [5] and Sablin et al. [6].

The pharmacological reason for the absence of an absolute cross-resistance between sorafenib and sunitinib remains unclear. A different pattern of binding affinities for their common targets may play a role as well as the existence of yet undescribed differing targets within the complex kinase-controlled cancer-related signalling pathways. Washout periods between the application of the first and second TKI may additionally be helpful in restoring the sensitivity of the tumour, as Sablin et al. [6] suggest according to their study design.

In their study with 29 patients receiving a sorafenib–sunitinib sequence and 20 patients receiving a sunitinib–sorafenib sequence, Dudek et al. [5] observed a longer disease control in the group starting with sorafenib (median overall PFS 78 weeks vs. 37 weeks and overall OS 102 weeks vs. 45 weeks). Comparable advantages of a sorafenib–sunitinib sequence were calculated by Sablin et al. [6] in their study with 90 patients (median overall OS 135 weeks vs. 82 weeks). In the largest two-arm study with both sequences conducted so far at 10 Italian centres, Porta et al. analysed the data of 176 patients of whom 85 started the TKI sequence with sorafenib and 91 with sunitinib. The mean overall PFS for the sor-sun-group was 17.2 months and for the sun-sor-group was 11.7 months (P = 0.0028) [7].

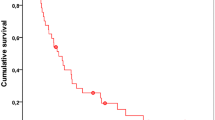

In our study, these results could not be confirmed. Its data reveal no statistically significant differences in PFS between the two sequences and an almost equal OS in both groups. In general, however, our study confirms the benefits of a sequential TKI therapy. The application of either sunitinib or sorafenib as a second TKI leads to a clearly prolonged PFS in both patient groups (Fig. 2).

Among the two-arm studies evaluating the usefulness of TKI sequences, our study belongs to the larger ones and covers a longer observation period than all others. Due to the retrospective character of our study, we have been analysing information from health records which had originally been filed for daily medical practice and not for scientific purposes. We included patients from both hospitals and community-based oncological practices. This design constitutes a major limitation of our study: Documentation is partly incomplete and does not fully match all data fields in our templates. At the same time, however, this design constitutes an important strength of our study: It reflects a real-life scenario in which it endorses observations hitherto confined to studies of a narrower scope. It encompasses patients from clinical studies and expanded access programs as well as those that were treated with the commercially available drug in a community-setting. It includes patients with all sorts of histologies, with brain metastases, in several therapy lines, and with a poorer performance than would have been allowed for in a clinical trial. Taking this width of our approach into consideration, it is impressive to realize that a sequential TKI therapy—regardless of its order—may grant mRCC patients a median overall survival time of almost 2.5 years.

Drawing on data from a realistic, real-life background, our retrospective analysis confirms the lack of cross-resistance between sorafenib and sunitinib. It underscores previous findings that the sequential use of these TKIs is of considerable clinical benefit by achieving an overall survival time of 2.5 years for patients with mRCC. However, based on this retrospective analysis, no clear recommendation for a preferred second-line agent can be given. Further and larger studies, preferably of a prospective character, particulary the SWITCH trial [NCT00732914], are necessary to solve this issue.

References

Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Szczylik C, Oudard S, Siebels M, Negrier S, Chevreau C, Solska E, Desai AA, Rolland F, Demkow T, Hutson TE, Gore M, Freeman S, Schwartz B, Shan M, Simantov R, Bukowski RM, TARGET Study Group (2009) Sorafenib for treatment of renal cell carcinoma: final efficacy and safety results of the phase III treatment approaches in renal cancer global evaluation trial. J Clin Oncol 27:3312–3318

Motzer RJ, Hutson E, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Pili R, Bjarnason GA, Garcia-del-Muro X, Sosman JA, Solska E, Wilding G, Thompson JA, Kim ST, Chen I, Huang X, Figlin RA (2009) Overall survival and updated results for Sunitinib compared with interferon alpha in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 27:3584–3590

Tamaskar A, Garcia JA, Elson P, Wood L, Mekhail T, Dreicer R, Rini BI, Bukowski RM (2008) Antitumour effects of sunitinib or sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who received prior antiangiogenic therapy. J Urol 179:81–86

Eichelberg C, Heuer R, Chun FK, Hinrichs K, Zacharias M, Huland H, Heinzer H (2008) Sequential use of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a retrospective outcome analysis. Eur Urol 54:1373–1378

Dudek AZ, Zolnieriek J, Dham A, Lindgren BR, Szczylik C (2009) Sequential therapy with sorafenib and sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 115:61–67

Sablin MP, Negrier S, Ravaud A, Oudard S, Balleyguier C, Gautier J, Celier C, Medioni J, Escudier B (2009) Sequentiel sorafenib and sunitinib for renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 182:29–34

Porta C, Procopio G, Sabbatini R (2010) Retrospective analysis of the sequential use of sorafenib and sunitinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Onkologie 33(Suppl 2):abstr.PO119

Larkin J, Gore M (2010) Is advanced renal cell carcinoma becoming a chronic disease? Lancet 376:574–575

Stadler WM, Figlin RA, McDermott FD, McDermott DF, Dutcher JP, Knox JJ, Miller WH Jr, Hainsworth JD, Henderson CA, George JR, Hajdenberg J, Kindwall-Keller TL, Ernstoff MS, Drabkin HA, Curti BD, Chu L, Ryan CW, Hotte SJ, Xia C, Cupit L, Bukowski RM, ARCCS Study Investigators (2010) Safety and efficacy results of the advanced renal cell carcinoma sorafenib expanded access program in North America. Cancer 116:1272–1280

Beck J, Procopio I, Negrier S (2009) Final analysis of a large open-label, noncomparative, phase 3 study of sorafenib in European patients with advanced RCC (EU-ARCCS). Eur J Cancer Suppl 7:434

Gore ME, Szczylik C, Porta C, Bracarda S, Bjarnason GA, Oudard S, Hariharan S, Lee SH, Haanen J, Castellano D, Vrdoljak E, Schöffski P, Mainwaring P, Nieto A, Yuan J, Bukowski R (2009) Safety and efficacy of sunitinib for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: an expanded-access trial. Lancet Oncol 10:757–763

Acknowledgments

Data acquisition and management was supported by ioMedico and Bayer Schering HealthCare.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Herrmann, E., Marschner, N., Grimm, M.O. et al. Sequential therapies with sorafenib and sunitinib in advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma. World J Urol 29, 361–366 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-011-0673-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-011-0673-4