Abstract

To study sexual activity, the prevalence of sexual dysfunction and related help-seeking behaviours among mature adults in Spain, a telephone survey was conducted in Spain in 2001–2002. This was completed by 750 men and 750 women aged 40–80 years. Eighty-eight percent of men and 66% of women had engaged in sexual intercourse during the 12 months preceding the interview. Early ejaculation (31%) and lack of sexual interest (17%) were the most common male sexual problems. A lack of sexual interest (36%) and an inability to reach orgasm (28%) were the most common female sexual problems. Approximately 80% of men and women with a sexual problem had not sought help from a health professional. Many men and women in Spain report continued sexual interest and activity into middle age and beyond. Although a number of sexual problems are highly prevalent, few people seek medical help.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Interest in the sexual problems experienced by middle-aged and older individuals has increased considerably in recent years, due at least in part to the development of convenient and effective oral treatments for male erectile dysfunction (ED). Studies investigating the prevalence of sexual problems among middle-aged and elderly people have been conducted in a number of European countries [5, 8, 13, 14, 17]. These have mostly investigated the prevalence of the male sexual problems of ED and early ejaculation, and their related risk factors; however, fewer studies of female sexual dysfunction have been conducted in Europe [4, 23]. Furthermore, little is known about the average frequency of sexual activity and the importance of sexual relationships among mature men and women, although the few studies that have examined sexuality in these age groups have reported that sexual interest and activity persist into middle and older age [6, 12, 19].

The published studies of the prevalence and correlates of sexual problems in European populations have used widely differing study designs and definitions, which makes valid cross-country comparison difficult. Moreover, there are currently no recommendations concerning how men or women can manage or overcome their sexual problems, and there are no studies that allow a comparison of sexual behaviours across many different countries.

The global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors (GSSAB) was a population survey of 27,500 men and women aged 40–80 years in 29 countries around the world [16, 20, 22]. Here, we report the results from the respondents in Spain, and compare the sexual behaviours, and the prevalence of sexual dysfunction and help-seeking patterns in this country with those seen in other Northern and Southern European regions.

Methods

Using a random-digit dialling sampling design, computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATIs) were carried out in Spain and in other Southern (France, Italy) and Northern (Austria, Belgium, Germany, Sweden, UK) European countries during 2001 and 2002. The respondents were randomly selected by asking for the man or woman in the household between 40 and 80 years of age (participants were interviewed by interviewers of the same gender). Women and men were sampled in approximately equal numbers.

The questionnaire requested information concerning demographics, general health, relationships, and sexual behaviours, beliefs and attitudes. The subjects were asked if they had engaged in sexual intercourse during the previous year and the presence of sexual dysfunction was assessed by means of two sequential questions. The respondents were first asked whether they had ever experienced one or more of the sexual problems listed in Tables 2 and 3 for a period of 2 months or more during the previous year, and those who answered positively were then asked to specify if they experienced it ‘occasionally’, ‘sometimes’ or ‘frequently’.

We used logistic regression to investigate potential factors associated with selected sexual dysfunction. In these analyses, the presence of a sexual dysfunction was coded only for those respondents who reported experiencing the problem frequently or periodically, while those who indicated that they experienced the problem only occasionally were recoded to indicate no sexual dysfunction.

The subjects who reported having a sexual problem were asked whether they had sought help or advice from a series of sources. The listed options included: ‘Talked to partner’, ‘Talked to a medical doctor (other than a psychiatrist)’, ‘Looked for information anonymously (in books/magazines or on the Internet)’, ‘Talked to family member or friend’, ‘Taken prescription drugs/devices or talked to pharmacist’, ‘Talked to psychiatrist or psychologist or marriage counsellor’, ‘Talked to a clergy person or religious adviser’, ‘Called a telephone help line’, ‘Other—please specify’. More than one source could be indicated.

The subjects with sexual problems who did not consult a physician were asked why they had not done so, and offered a list of 14 possible reasons (from which they were to check all that applied). The reasons included attitudes and beliefs regarding the sexual problem and the patient–doctor relationship. All respondents (irrespective of whether they reported any sexual problems) were also asked ‘During a routine office visit or consultation in the past 3 years, has your physician asked you about possible sexual difficulties without you bringing it up first?’ (yes/no) and ‘Do you think a doctor should routinely ask patients about their sexual function?’ (yes/no).

The categorisation of household income as ‘low’, ‘medium’ or ‘high’ was based on the distribution of income in each country in order to make it possible to compare nations with different absolute mean incomes.

The prevalence of a specific characteristic was calculated by dividing the number of cases by the corresponding population. The denominator for the calculation of the prevalence of sexual problems was the number of sexually active people (i.e. at least one episode of intercourse during the previous year). The prevalence estimates were age-standardised using the age distribution of the Spanish population (by gender when appropriate), and are given with their confidence intervals (CI) [11].

Results

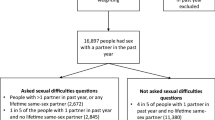

Characteristics of study population

Overall, 11,957 individuals were contacted, 5,373 of whom were not eligible to participate. Of the 6,584 eligible individuals, 1,692 refused to participate at introduction, while 3,392 interrupted the interview. A total of 1,500 individuals (750 men and 750 women) completed the survey, for a response rate of 23%. Table 1 presents data on selected characteristics of the study sample standardised for the age distribution of the Spanish population. The majority of the subjects were married or involved in an ongoing partnership (80.7% of men and 70.8% of women) (Table 1). Almost one-half of the men (49.5%) and 22.1% of the women were employed. Overall, more than one-half of men (69.2%) and women (56.3%) said they were in good or excellent general health.

Eighty-eight percent of men and 66.2% of women said that they had had sexual intercourse during the 12 months preceding the interview, while 39.9% of men and 29.9% of women engaged in sexual intercourse regularly (i.e. more than once a week).

Prevalence of sexual problems

Early ejaculation was the most common male sexual problem, and it was reported by 31.2% of the sexually active men in Spain (19.3% of all sexually active men said that they experienced this problem periodically or frequently) (Table 2). Overall, the prevalence of early ejaculation was up to twice as high among men in Spain compared with other European regions. Lack of sexual interest was the second most common male sexual problem in Spain, reported by 16.9% of sexually active men (8.2% said that they experienced this problem periodically or frequently), followed by an inability to reach orgasm, which was reported by 15.3% of sexually active men (6.3% said that they experienced this problem periodically or frequently). The prevalence of these two sexual problems was also somewhat higher among men in Spain than in other European regions, although the difference was not as marked as for early ejaculation. Erectile difficulties were experienced by 12.7% of men in Spain, indicating a prevalence similar to that reported in other European regions. The other sexual problems investigated (a lack of sexual pleasure and pain during sexual intercourse) were each experienced by about 10% or less of sexually active men and were similarly prevalent in Spain and other parts of Europe.

Lack of sexual interest (36.0%), inability to reach orgasm (27.8%) and lack of pleasure in sex (25.1%) were the most common sexual problems reported by sexually active women in Spain (Table 3). Approximately two-thirds of the women who reported each of these problems said that they experienced it frequently or periodically. The prevalence of these problems among sexually active women in Spain was substantially higher than in other European regions. The other sexual problems investigated, lubrication difficulties and pain during sexual intercourse, were experienced by 12.5 and 10.7% of sexually active women, respectively, and were similarly prevalent in Spain and other parts of Europe. Physical/health, demographic and socioeconomic factors associated with three selected sexual dysfunctions in men and women are summarised in Table 4 [odds ratios (OR) from logistic regression]. Increasing age was a significant correlate of erectile difficulties in men (OR was 3.02 at age 50–59 years and 3.50 at 60–80 years, compared with the referent of 40–49 years), while in women the only significant effect of age was that the age range of 50–59 years (the age at which many women experience the menopause) was associated with an inability to reach orgasm (OR 1.85 compared with the referent of 40–49 years). In men, the diagnosis of a number of common health conditions—depression, hypertension and diabetes—was also associated with erectile difficulties, and depression was also a significant correlate of lack of sexual interest. Interestingly, a higher level of education was negatively associated with the most common male sexual problem, early ejaculation. Among women, the only other significant correlates were a diagnosis of depression with lack of sexual interest (OR 1.61) and heart disease with lubrication difficulties (OR 2.70).

Help-seeking behaviour

The prevalence of selected help-seeking behaviours for sexual problems among men and women in Spain are summarised in Table 5 (values for respondents from other European regions are also included to allow comparisons). Of the Spanish respondents who were sexually active and reported at least one sexual problem, 38.9% of men and women did not take any action (i.e. they did not seek any help or advice). A similar proportion of men (17.7%) and women (18.6%) reported talking to a medical doctor about their sexual problem(s). This value was lower than in the rest of the Southern European region but comparable with Northern Europe. The majority of men (79.4%) and women (80.2%) had not sought advice from a health professional. Overall, patterns of help-seeking behaviours were similar for men and women in Spain, and talking to their partner was the most common action taken by both men and women (49.9 and 51.5%, respectively).

Factors associated with seeking medical help for sexual problems

Some of the factors that might be associated with seeking medical help for sexual problems among men and women in Spain were investigated using logistic regression, and the findings (OR) are summarised in Table 6. The effects of increasing age were quite different for men and women. While among men, increasing age was associated with an increasing likelihood of seeking medical help for sexual problems (which was statistically significant for each age group compared with the referent group aged 40–49 years), older women were less likely to seek medical help, although this effect was significant only for the 60–69 years age group compared with the referent group aged 40–49 years. Certain sexual problems were associated with a greater likelihood of seeking medical help. Erectile difficulties in men (OR 3.01) and lubrication difficulties in women (OR 2.57) were significant correlates of seeking medical help for sexual problems. Men who had been asked by a doctor about possible sexual difficulties during a routine visit in the past 3 years were also significantly more likely to report seeking medical help for sexual problems (OR 4.16). The effect of this factor in women was not significant.

Attitudes and beliefs about diagnosis and treatment of sexual problems

The most common reasons cited among the respondents in Spain for not consulting a doctor about sexual problems were a belief that it is a normal part of aging or being comfortable as he/she is (53.7% of men and 61.0% of women), not being comfortable talking to a doctor about such problems (49.2% of men and 53.3% of women) and thinking it is not very serious or waiting for the problem to go away (42.7% of men and 44.1% of women) (Table 7). These values showed some interesting differences to those seen in other European regions. Lack of access to or affordability of medical care and embarrassment about discussing sexual problems with their medical doctor were cited considerably more frequently in Spain than in the rest of Europe. A lack of perception of a sexual problem as a treatable medical condition was somewhat less common among men and women in Spain than in other parts of Europe. Very few of the respondents in Spain had been asked by a doctor about possible sexual difficulties during a routine visit in the past 3 years (5.9% of men and 6.5% of women). More than one-half (51.6%) of men and 39.5% of women in Spain thought that a doctor should routinely ask patients about their sexual function. The prevalence of this attitude was similar to that seen in other parts of Europe.

Discussion

This is the first study to report population-level data from middle-aged and older people in Spain concerning sexual behaviour, the prevalence of sexual dysfunction and associated help-seeking behaviours in a manner that allows direct comparisons with other European regions.

A major strength of the GSSAB survey lies in its cross-national population sample and the use of a common method of data collection. Face-to-face interviews were avoided because they may embarrass people talking about private and sensitive issues, or induce respondents to give socially desirable answers [2]. We considered only the sexual problems that persisted with moderate to higher frequency as ‘dysfunction’ [21]. This method is equivalent to using two sequential screening tests, and thus minimises the false positive rate; it is therefore likely that the prevalence of sexual dysfunction is under-reported in comparison with studies that used more sensitive (and less specific) methods.

The overall response rate in Spain (23%) was not high, but the prevalence of self-reported health conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes and smoking in the GSSAB (data not shown here) was consistent with published age- and gender-specific figures [9, 15, 18, 24, 25, 28]. This leads us to believe that the reason for refusing to participate in the study was a general unwillingness to undergo a telephone interview, and that this is unlikely to have introduced a bias in the estimates of the prevalence of sexual behaviours and dysfunction. It also appears to indicate that the study population was broadly representative of the Spanish population. This assumption is further supported by the observation that the prevalence of ED among Spanish men in the GSSAB is comparable to the estimate (12.1%) determined in an earlier cross-sectional national study conducted in Spain among 2,276 men aged 25–70 years [17].

In the GSSAB sample of mature adults in Spain, a diagnosis of depression was found to be a significant correlate of ED in men and lack of sexual interest in both men and women. Furthermore, a lack of sexual interest was considerably more common in men and women in Spain than in other European regions. Together with the conclusions of a cross-sectional primary care study by Gabarron Hortal et al. [10], which found a high prevalence and a high rate of underdiagnosis of depression in Spain (Barcelona), these observations highlight the importance of a link between depression and sexual problems. The association is not simple, however, and some studies conducted in other areas of Spain have not shown a high prevalence of depression. The ODIN study concluded that Spain (the Spanish part of the study was conducted in Santander) has a relatively low prevalence of depressive disorders compared with other European countries, while a third study concluded that the prevalence of depression in Zaragoza was similar to that in the Liverpool (UK) [3, 7]. The possible contribution of anti-depressant therapies, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), to the prevalence of sexual problems (sexual dysfunction is one of the most persistent and frequent adverse effects of SSRIs) should also be taken into account when considering any association between depression and sexual function [1]. Despite the correlation between sexual problems and depression, the relationship is most probably bi-directional, i.e. sexual problems may both follow depression and depression may be a consequence of a sexual dysfunction. We cannot discern the causal direction in these cross-sectional data.

Our findings indicate that feelings of awkwardness or embarrassment may be deterring Spanish men and women from raising the subject of their sexual problems with their doctor. Furthermore, they show that doctors in Spain—in common with the rest of Europe—rarely ask patients about their sexual health during a routine consultation, even though this would be welcomed by a substantial proportion of men and women and would appear to encourage medical help-seeking for sexual problems, at least in men. This apparent reluctance—in both doctors and patients—to begin a discussion about sexual functioning may be due, at least in part, to erroneous beliefs regarding sexuality that have been documented among Spanish healthcare professionals and primary healthcare users [26, 27].

In conclusion, our results show that in Spain, as in other European regions, middle-aged and elderly men and women continue to show sexual interest and activity, in spite of the high prevalence of a number of sexual dysfunctions. Only a minority of the men and women who experience sexual difficulties seek medical help for these problems, often due to embarrassment or lack of access to a physician. Appropriate educational programmes for both patients and healthcare professionals may be required to dispel common myths and misconceptions and enable older adults to continue to enjoy a satisfying sexual life.

References

Arias F, Padin JJ, Rivas MT, Sanchez A (2000) Sexual dysfunctions induced by serotonin reuptake inhibitors (article in Spanish). Aten Primaria 26:389–394

ASCF principal investigators and their associates (1992) Analysis of sexual behaviour in France (ACSF). A comparison between two modes of investigation: telephone survey and face-to-face survey. AIDS 6:315–323

Ayuso-Mateos JL, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Dowrick C, Lehtinen V, Dalgard OS, Casey P, Wilkinson C, Lasa L, Page H, Dunn G, Wilkinson G (2001) Depressive disorders in Europe: prevalence figures from the ODIN study. Br J Psychiatry 179:308–316

Barlow DH, Cardozo LD, Francis RM, Griffin M, Hart DM, Stephens DW (1997) Urogenital ageing and its effect on sexual health in older British women. Br J Obstet Gynecol 104:87–91

Blanker MH, Bosch JLHR, Groeneveld FPMJ, Bohnen AM, Prins A, Thomas S, Hop WCJ (2001) Erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction in a community-based sample of men 50–78 years old: prevalence, concern, and relation to sexual activity. Urology 57:763–768

Deacon S, Minichiello V, Plummer D (1995) Sexuality and older people: revisiting the assumptions. Educ Gerontol 21:497–513

Dewey ME, de la Camara C, Copeland JR, Lobo A, Saz P (1993) Cross-cultural comparison of depression and depressive symptoms in older people. Acta Psychiatr Scand 87:369–373

Dunn KM, Croft PR, Hackett GI (1998) Sexual problems: a study of the prevalence and need for care in the general population. Fam Pract 15:519–524

Eurostat. Health statistics—key data on health 2002—data 1970–2001

Gabarron Hortal E, Vidal Royo JM, Haro Abad JM, Boix Soriano I, Jover Blanca A, Arenas Prat M (2002) Prevalence and detection of depressive disorders in primary care (article in Spanish). Aten Primaria 29:329–336

Gardner MJ, Altman DG (1987) Confidence intervals rather than P value: estimation rather than hypothesis testing. Br Med J 292:746–750

Gott M, Hinchliff S (2003) How important is sex in later life? The views of older people. Soc Sci Med 56:1617–1628

Guiliano F, Chevret-Measson M, Tsatsaris A, Reitz C, Murino M, Thonneau P (2002) Prevalence of erectile dysfunction in France: results of an epidemiological survey of a representative sample of 1004 men. Eur Urol 42:382–389

Helgason AR, Adolfsson J, Dickman P, Arver S, Fredrikson M, Gothberg M, Steineck G (1996) Sexual desire, erection, orgasm and ejaculatory functions and their importance to elderly Swedish men: a population-based study. Age Ageing 25:285–291

Jimenez Ruiz CA, Fernando Masa J, Sobradillo V, Gabriel R, Miravitlles M, Fernandez-Fau L, Villasante C, Viejo JL (2000) Prevalence of and attitudes towards smoking in a population over 40 years of age (article in Spanish). Arch Bronconeumol 36:241–244

Laumann EO, Nicolosi A, Glasser DB, Paik A, Gingell C, Moreira ED, Wang T, GSSAB Investigators’ Group (2005) Sexual problems among women and men aged 40–80 years: prevalence and correlates identified in the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Impot Res 17:39–57

Martin-Morales A, Sanchez-Cruz JJ, Saenz de Tejada I, Rodriguez-Vela L, Jimenez-Cruz JF, Burgos-Rodriguez R (2001) Prevalence and independent risk factors for erectile dysfunction in Spain: results of the Epidemiologia De La Disfuncion Erectil Masculina study. J Urol 166:569–575

Masia R, Sala J, Rohlfs I, Piulats R, Manresa JM, Marrugat J (2004) Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in the province of Girona, Spain: the REGICOR study (article in Spanish). Rev Esp Cardiol 57:261–264

Matthias RE, Lubben JE, Atchison KA, Schweitzer SO (1997) Sexual activity and satisfaction among very old adults: results from a community-dwelling Medicare population survey. Gerontologist 37:6–14

Moreira ED, Brock G, Glasser DB, Nicolosi A, Laumann EO, Paik A, Wang T, Gingell C, GSSAB Investigators’ Group (2005) Help-seeking behavior for sexual problems: the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Int J Clin Pract 59:6–16

Moynihan R (2003) The making of a disease: female sexual dysfunction. Br Med J 326:45–47

Nicolosi A, Laumann EO, Glasser DB, Moreira ED, Paik A, Gingell C, GSSAB Investigators’ Group (2004) Sexual behavior and sexual problems after the age of 40: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors (GSSAB). Urology 65:991–997

Osborn M, Hawton K, Gath D (1988) Sexual dysfunction among middle-aged women in the community. Br Med J 296:959–962

Pineda Cuenca M, Custardoy Olavarrieta J, Andreu Ruiz MT, Ortin Arroniz JM, Cano Montoro JG, Medina Ferrer E (2002) Prevalence study of cardiovascular risk factors in a health area (article in Spanish). Aten Primaria 30:207–213

Segura Fragoso A, Rius Mery G (1999) Cardiovascular risk factors in a rural population of Castilla-La Mancha (article in Spanish). Rev Esp Cardiol 52:577–588

Van-der Hofstadt CJ, Ruiz MT (1994) Disturbances in sexual function: analysis of conditioning factors of an effective health care center (article in Spanish). Med Clin (Barc) 103:125–128

Van-der Hofstadt CJ, Ruiz MT, Baena C, Sanchez A (1995) Sexual myths in an adult population (article in Spanish). Med Clin (Barc) 105:691–695

Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Banegas JR, Giampaoli S, Hense HW, Joffres M, Kastarinen M, Poulter N, Primatesta P, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Stegmayr B, Thamm M, Tuomilehto J, Vanuzzo D, Vescio F (2003) Hypertension prevalence and blood pressure levels in 6 European countries, Canada, and the United States. JAMA 289:2363–2369

Acknowledgements

The global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors was funded by Pfizer Inc. The authors acknowledge the contribution of their colleagues on the study’s international Advisory Board: Gerald Brock (Canada), Jacques Buvat (France), Uwe Hartmann (Germany), Sae-Chul Kim (Korea), Rosie King (Australia), Edward Laumann (USA), Bernard Levinson (South Africa), Ken Marumo (Japan), Alfredo Nicolosi (Italy) and Ferruh Simsek (Turkey).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moreira, E.D., Glasser, D.B., Gingell, C. et al. Sexual activity, sexual dysfunction and associated help-seeking behaviours in middle-aged and older adults in Spain: a population survey. World J Urol 23, 422–429 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-005-0035-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-005-0035-1