Abstract

Objective

To investigate the usefulness of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in the evaluation of renal masses.

Methods

This study included 255 patients with renal masses. Ages ranged from 18–86 years. CEUS was used for determining malignancy or benignancy and findings were correlated with the histopathological outcome. Out of 255 lesions, 212 lesions were malignant (83.1%) and 43 were benign (16.9%). Diagnostic accuracy was tested using the histopathological diagnosis as the gold standard.

Results

CEUS showed a sensitivity of 99.1% [95% confidence interval (CI): 96.7%, 99.9%], a specificity of 80.5% (CI: 65.1%, 91.2%), a positive predictive value of 96.4% (CI: 93.0%, 98.4%) and a negative predictive value of 94.3% (CI: 80.8%, 99.3%). Kappa for diagnostic accuracy was κ = 0.85 (CI: 0.75, 0.94). Of 212 malignant lesions, 200 renal cell carcinomas and 12 other malignant lesions were diagnosed. Out of 43 benign lesions, 10 angiomyolipomas, 3 oncocytomas, 8 renal cysts and 22 other benign lesions were diagnosed.

Conclusion

CEUS is an useful method to differentiate between malignant and benignant renal lesions. To date, to our knowledge, this is the largest study in Europe for the evaluation of renal lesions using CEUS with a histopathological validation.

Key Points

• CEUS helps clinicians detect and characterise unclear solid and cystic renal lesions

• CEUS shows a high diagnostic accuracy in the characterization of these lesions

• Proper surgical treatment or follow-up can be given with better diagnostic confidence

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With the almost ubiquitous use of ultrasound across all clinical disciplines, incidentally found unclear renal lesions are more commonly seen nowadays and preoperative clinical management and characterisation of these lesions is important for patient care [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Mainly, incidentally found renal lesions are benign simple renal cysts and malignancy can be safely ruled out using different imaging methods [7,8,9]. The main differential diagnosis for solid or cystic renal lesions is the renal cell carcinoma that shows an incidence rate of 3% of all malign neoplasms and is one of the most common tumours of the urinary tract [2]. In the up-to-date 2014 European guidelines for renal cell carcinoma, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CE-CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the initial imaging modalities of choice for the characterisation and diagnosis of renal cell carcinomas. In patients with chronic renal failure or a known allergy to contrast media containing iodine or gadolinium, contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) can be used as a complementary option [9, 10]. Different to CE-CT and MRI, ultrasound contrast agents are purely intravascular and do not diffuse into the interstitial space [11,12,13]. Additionally, they can be used independently from thyroid and renal function and show a low incidence of adverse events like an anaphylactic reaction that only occurs in 1 of 10,000 cases [14, 15]. Nowadays, CEUS is used in clinical daily routine as a fast, low-risk and cost-effective modality for the local diagnosis and staging of renal cell carcinomas [16,17,18,19]. Using CEUS, malignant renal lesions show an enhancement pattern different from the surrounding healthy renal parenchyma, making it possible to differentiate between benign and malignant renal lesions (see Table 1). Unfortunately, some benign renal lesions like oncocytomas are hard to differentiate from malignant lesions like renal cell carcinomas because of similar enhancement patterns in CEUS, CE-CT and MRI [20, 21]. This retrospective analysis study was performed to compare the sensitivity and specificity of CEUS in the evaluation of unclear renal lesions to the histopathological outcome as a gold standard.

Methods

Between 2005 and 2015, a total of 981 patients with unclear cystic or solid renal lesions were consecutively examined at our department using CEUS. We retrospectively analysed a sub-cohort of this study cohort with a total of 255 patients with a single cystic or solid renal lesion who additionally received a histological workup of this lesion after surgical removal of the lesion or biopsy. From the initial 981 patients with a CEUS examination, we excluded all patients without histopathological data (e.g. patients with Bosniak I, II or II F cysts). The local ethics committee approved this study. All study data were collected in compliance with the principles of the Helsinki/Edinburgh Declaration of 2002. Oral and written informed consent of all patients was obtained prior to each CEUS examination at the time of the examination.

The CEUS examinations were conducted with high-end ultrasound systems with up-to-date CEUS-specific examination protocols available at the time of the examination (Sequoia/S2000/S3000, Siemens Healthineers; HDI 5000/iU22/EPIQ 7/Affiniti, Philips Ultrasound; LOGIQ E9, GE Healthcare). Used ultrasound probes included C6-1 HD, C5-1, C4-1 and V4-1 probes available at the time of the examination. All CEUS examinations were initially performed and interpreted by a single radiologist with more than 15 years of experience in CEUS and a corresponding level 3 training level of the European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (EFSUMB). A low mechanical index (always < 0.4) was used for examination to avoid unintentional destructions of microbubbles.

A second-generation blood pool contrast agent media (SonoVue®, Bracco) was used in all examinations and was administered through a peripheral 20–22-G needle as a bolus injection followed by a flush of 5 to 10 ml of 0.9% saline solution (0.9% NaCl). Contrast agent (1.6 to 2.4 ml) was administered in most cases and with a maximum of 4.8 ml and minimum of 1.0 ml, depending on the used ultrasound machine and ultrasound probe. In most cases, a single dose of contrast agent was given. After the injection of the contrast agent, cine loops were acquired and stored in the picture archiving and communication system (PACS) of our department. Examination time ranged between 3 and 5 minutes for the whole examination. If additional imaging was necessary, a total of up to three injections of contrast agent was given.

We retrospectively obtained from the patients record files the results of the initial CEUS examinations. All findings of the CEUS examinations were reported at the time of the examination without knowing the histopathological results. Lesions were classified as malignant or benign depending on their enhancement behaviour in the CEUS examination (see Table 1). We additionally retrospectively evaluated all stored cine loops from our PACS to assess the stored cine loops by a second independent reader who was blinded to the histopathological outcome. We also calculated the intraclass correlation coefficient using two-way mixed average measures on absolute agreement [ICC (3, k)]. The second reader of the examinations was a radiologist with more than 3 years of experience in CEUS and a corresponding level 1 training level of the EFSUMB.

For statistical analysis, diagnostic accuracy of CEUS was tested using sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV). Additionally, exact 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for all values.

Results

Patient ages ranged from 18 to 86 years [mean age 62 years; standard deviation (SD) ± 13]. Out of the 255 renal lesions, a total of 212 lesions were malignant (83.1%) and 43 were found to be benign (16.9%) in the final histopathological report. Histological material could be gathered after surgical removal of the lesion, after biopsy or after fine-needle aspiration.

Depending on their enhancement pattern (see Table 1), CEUS showed a sensitivity of 99.1% (95% CI: 96.7%, 99.9%), a specificity of 80.5% (95% CI: 65.1%, 91.2%), a PPV of 96.4% (95% CI: 93.0%, 98.4%) and an NPV of 94.3% (95% CI: 80.8%, 99.3%). Kappa for diagnostic accuracy was κ = 0.85 (95% CI: 0.75, 0.94).

Out of the 212 malignant lesions, a total of 130 clear cell renal carcinomas, 59 papillary renal cell carcinomas, 7 chromophobe renal cell carcinomas, 4 combined clear cell and papillary renal cell carcinomas and 12 other malignant lesions, e.g. metastases, were diagnosed (mean lesion size 2.3 cm; minimal lesion size 0.7 cm; maximal lesion size 7.8 cm). Out of the 43 benign lesions, a total of 10 angiomyolipomas, 3 oncocytomas, 8 benign renal cysts and 22 other benign lesions were diagnosed (18 pseudotumours and 4 renal abscesses; mean lesion size 1.8 cm; minimal lesion size 0.8 cm; maximal lesion size 6.3 cm). Pseudotumours showed characteristic features of a solid lesion using conventional B-mode ultrasound and a persistent isoenhancement in all phases using CEUS and were all biopsied for further evaluation. Histological work-up always showed non-neoplastic tissue. The four renal abscesses showed a well-defined hypoechoic area with sharp margins suggesting a potentially malignant lesion using B-mode ultrasound and a non-enhancement using CEUS and were also biopsied for further evaluation. Histological work-up then revealed a renal abscess. Using CEUS, 10 lesions were falsely identified as malignant or benign, whereas 8 lesions were false positive and 2 lesions false negative. The eight false-positive lesions included five oncocytomas or angiomyolipomas (lesion size ranged from 0.8 to 3.2 cm) and three Bosniak category III cystic lesions (lesion size ranged from 1.4 cm to 3.6 cm; see Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4). The two false-negative lesions consisted of two clear cell renal cell carcinomas (lesion size 0.8 and 0.9 cm), both of which did not exhibit an arterial enhancement pattern in the arterial phase, maybe due to the fact that it was missed during the histopathological examination that these lesions could have shown mixed features of a papillary and clear cell renal cell carcinoma. In our examination, both lesions showed a continuous hypoenhancement in all phases.

a Hyperechoic renal lesion in a patient visualised in native B-mode ultrasound (yellow arrows). The patient was referred from his urologist for further evaluation of this unclear renal lesion. b There is no major vascularisation that can be visualised using colour-Doppler (yellow arrows), rather suggesting a benign renal lesion. CEUS was recommended for further verification. c CEUS shows a hypoenhancement of the unclear renal lesion (yellow arrows) in the arterial phase and a continuing hypoenhancement in the venous phase (shown in this picture), suggesting a papillary/chromophobic renal cell carcinoma. This diagnosis of a papillary renal cell carcinoma was later confirmed after surgical resection

a Hyperechoic renal lesion in a patient visualised in native B-mode ultrasound (red arrows). The patient was referred from his urologist for further evaluation of this unclear renal lesion. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound was suggested for further evaluation of this lesion. b Contrast-enhanced ultrasound shows a hypoenhancement of the unclear renal lesion (red arrows) in the venous phase, suggesting a malignant renal lesion. c CEUS shows a continuing and persistent hypoenhancement in the delayed phase, strengthening the suggested diagnosis of a malignant renal lesion in line with sonographic features of a papillary/chromophobic renal cell carcinoma (red arrows). However, after surgical removal, the histopathological results showed a benign angiomyolipoma, showing that angiomyolipomas show inconstant features during CEUS and can be misinterpreted as a malignant lesion

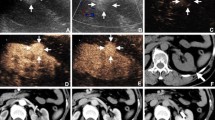

a Hypoechoic cystic renal lesion in a patient with the suggested diagnosis of a renal cell carcinoma (white arrows). The patient was referred for further verification of the diagnosis. b Using colour Doppler mode major, vascularisation of the cystic renal lesion can be visualised in line with sonographic features of a malignant renal lesion (white arrows). c CEUS shows an arterial hyperenhancement of the unclear renal lesion (white arrows) with evidence of necrotic areas suggesting a malignant renal lesion. d CEUS shows a hypoenhancement in the venous phase in line with an early venous wash-out suggesting a renal cell carcinoma (white arrows). The diagnosis was confirmed after surgical removal of the lesion

a Hyperechoic renal lesion in a patient visualised in native B-mode ultrasound (red arrows). The patient was referred from his urologist for further evaluation of this unclear renal lesion. b Colour Doppler shows some vascularisation inside the unclear renal lesion, rather suggesting a malignant lesion (red arrows). CEUS was recommended for further verification. c CEUS shows an isoenhancement in the arterial phase rather suggesting a benign renal lesion, as malignant renal cell carcinomas rather show a hypoenhancement in the arterial phase (red arrows). d CEUS shows a persistent isoenhancement of the lesion in the venous phase with no signs of a venous wash out or beginning hypoenhancement of the lesion (red arrows), suggesting a benign renal lesion, for example an oncocytoma. Neither an arterial hyperenhancement nor an arterial hypoenhancement or early wash-out during the nephrographic phase could be detected, suggesting a benign renal lesion. The diagnosis was histopathologically confirmed after biopsy

The calculated interrater reliability was r = 0.9 with a p ≤ 0.001 for the blinded read of the second reader which shows a great interobserver variability for two independent radiologists.

Discussion

Incidentally found renal lesions are a challenge to sufficiently characterise but critical for patient management. Although most malignant lesions can preoperatively be diagnosed with adequate certainty, some histopathological benign lesions are biopsied or surgically removed because of uncertain imaging results. CEUS can be used to evaluate unclear renal lesions with a high PPV and NPV. To our knowledge, this is the biggest study in Europe to date evaluating renal lesions using CEUS with a histopathological validation. The biggest study cohort of patients with unclear renal masses that were evaluated using CEUS in the USA included 306 patients and showed similar results [21]. The additional use of CEUS for these lesions can aid diagnosis and reduce the number of biopsies and surgical removal or can validate malignancy in lesions that otherwise only would be followed up. In this retrospective study, we demonstrated that CEUS shows a high PPV (96.4%), a good specificity (80.5%) and an excellent sensitivity (99.1%) for the prediction of a renal tumour comparable to other imaging modalities like CT or MRI. We could also demonstrate a great interobserver variability (r = 0.9) between two independent readers of the stored cine loops. These findings are in line with several previous studies conducted about this topic [21,22,23,24] and shows contradicting results to a previously conducted study by Haendl et al. described in 2009 in their well-conducted prospective study with a multireader assessment approach and a sequential analysis of enhancement phases a chaotic vascularisation pattern of renal cell carcinomas but with an only relative small cohort of 30 patients and with only 3 benign renal lesions in the study cohort all consisting of oncocytomas that can show inconstant imaging features using CEUS [25]. In our study, mostly oncocytomas and angiomyolipomas were misdiagnosed using cross-sectional imaging techniques, which is concordant to other studies that reported similar difficulties in the differentiation of these entities from malignant tumours due to imaging features of these lesions being similar to malignant lesions [25,26,27,28,29]. In our study, we had problems differentiating these lesions from malignant lesions independently from the size of the lesion as both small oncocytomas and angiomyolipomas (< 1 cm) and bigger oncocytomas and angiomyolipomas (> 1 cm) were misinterpreted as false positive. In general, it was more difficult to assess the vascularisation patterns of small renal lesions in comparison to bigger renal lesions.

For patients suffering from chronic renal failure or with impaired renal function CEUS can be used as an alternative imaging modality. CEUS can also be used in patients suffering from hyperthyroidism, with metal implants that are not suitable for MRI or known history of allergic reaction to iodine or gadolinium. Additionally, using CEUS adds the benefit of using a non-ionising radiation approach compared to CT and is much more cost-effective than using MRI. Furthermore, CEUS is a dynamic examination technique with the ability to repeat contrast agent administration multiple times because of the characteristic features of the used contrast agents that do not interfere with renal, thyroid or hepatic function. The high PPV and NPV of CEUS could reduce the number of CT and MRI examinations, the associated use of radiation and contrast agents with renal toxicity and the associated economic burden for the health system.

This study was limited by several factors. First of all, this was a retrospectively conducted single-centre study with only one radiologist evaluating the lesions at CEUS. Different equipment was used and contrast agent doses varied with patients depending on the CEUS techniques existing at the time of the examination. In this study, only a relatively small percentage of all unclear lesions were found to be benign (16.9%) in histopathological workup, which is much lower compared to the expected 45% from national statistics [30]. Additionally, there were no patients in our study population with the diagnosis of a pyelonephritis that may be visualised as a vascularised renal lesion using CEUS, because this diagnosis normally can be made based on clinical findings.

Conclusion

This study confirms the relevance of CEUS as an essential additional diagnostic tool. This relatively new method offers manifold ways of diagnosis and future oncological therapy. Establishing CEUS in clinical routine allows fast, correct, low-risk and cost-effective examinations. CEUS can be used for differentiation of unclear renal lesions, thus reducing the number of unnecessary biopsies or operations.

Abbreviations

- CE-CT:

-

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography

- CEUS:

-

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- NPV:

-

Negative predictive value

- PACS:

-

Picture archiving and communication system

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

References

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P et al (2007) Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 356(2):115–124

Hock LM, Lynch J, Balaji KC (2002) Increasing incidence of all stages of kidney cancer in the last 2 decades in the United States: an analysis of surveillance, epidemiology and end results program data. J Urol 167(1):57–60

Wallen EM, Pruthi RS, Joyce GF, Wise M, Urologic Diseases in America P (2007) Kidney cancer. J Urol 177(6):2006–2018 discussion 18–9

Woldrich JM, Mallin K, Ritchey J, Carroll PR, Kane CJ (2008) Sex differences in renal cell cancer presentation and survival: an analysis of the National Cancer Database, 1993–2004. J Urol 179(5):1709–1713 discussion 13

Kazmierski B, Deurdulian C, Tchelepi H, Grant EG (2018) Applications of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the kidney. Abdom Radiol (NY) 43(4):880–898

Sidhu PS, Cantisani V, Dietrich CF et al (2018) The EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations for the clinical practice of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in non-hepatic applications: update 2017 (Long version). Ultraschall Med 39(2):e2–e44

Bosniak MA (1991) The small (less than or equal to 3.0 cm) renal parenchymal tumor: detection, diagnosis, and controversies. Radiology 179(2):307–317

Rübenthaler J, Bogner F, Reiser M, Clevert DA (2016) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) of the kidneys by using the Bosniak classification. Ultraschall Med 37(3):234–251

Rübenthaler J, Paprottka K, D'Anastasi M, Reiser M, Clevert DA (2017) Diagnosis of perinephric retroperitoneal lymphangioma supported by contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS). Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 65(1):43–47

Ljungberg B, Bensalah K, Canfield S et al (2015) EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: 2014 update. Eur Urol 67(5):913–924

Greis C (2009) Ultrasound contrast agents as markers of vascularity and microcirculation. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 43(1–2):1–9

Greis C (2011) Summary of technical principles of contrast sonography and future perspectives. Radiologe 51(6):456–461

Rübenthaler J, Reiser M, Clevert DA (2016) Diagnostic vascular ultrasonography with the help of color Doppler and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Ultrasonography 35(4):289–301

Piscaglia F, Bolondi L, Italian Society for Ultrasound in M, Biology Study Group on Ultrasound Contrast A (2006) The safety of Sonovue in abdominal applications: retrospective analysis of 23188 investigations. Ultrasound Med Biol 32(9):1369–1375

ter Haar G (2009) Safety and bio-effects of ultrasound contrast agents. Med Biol Eng Comput 47(8):893–900

Escudier B, Porta C, Schmidinger M et al (2014) Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 25(Suppl 3):iii49–iii56

Clevert DA, Sterzik A, Braunagel M, Notohamiprodjo M, Graser A (2013) Modern imaging of kidney tumors. Urologe A 52(4):515–526

Rübenthaler J, Reimann R, Hristova P, Staehler M, Reiser M, Clevert DA (2015) Parametric imaging of clear cell and papillary renal cell carcinoma using contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS). Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 63(2):89–97

Reimann R, Rübenthaler J, Hristova P, Staehler M, Reiser M, Clevert DA (2015) Characterization of histological subtypes of clear cell renal cell carcinoma using contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS). Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 63(1):77–87

Houtzager S, Wijkstra H, de la Rosette JJ, Laguna MP (2013) Evaluation of renal masses with contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Curr Urol Rep 14(2):116–123

Barr RG, Peterson C, Hindi A (2014) Evaluation of indeterminate renal masses with contrast-enhanced US: a diagnostic performance study. Radiology 271(1):133–142

Gerst S, Hann LE, Li D et al (2011) Evaluation of renal masses with contrast-enhanced ultrasound: initial experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol 197(4):897–906

Clevert DA, Minaifar N, Weckbach S et al (2008) Multislice computed tomography versus contrast-enhanced ultrasound in evaluation of complex cystic renal masses using the Bosniak classification system. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 39(1–4):171–178

Sanz E, Hevia V, Arias F et al (2015) Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS): an excellent tool in the follow-up of small renal masses treated with cryoablation. Curr Urol Rep 16(1):469

Haendl T, Strobel D, Legal W, Frieser M, Hahn EG, Bernatik T (2009) Renal cell cancer does not show a typical perfusion pattern in contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Ultraschall Med 30(1):58–63

Fan L, Lianfang D, Jinfang X, Yijin S, Ying W (2008) Diagnostic efficacy of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in solid renal parenchymal lesions with maximum diameters of 5 cm. J Ultrasound Med 27(6):875–885

Tamai H, Takiguchi Y, Oka M et al (2005) Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in the diagnosis of solid renal tumors. J Ultrasound Med 24(12):1635–1640

Siegel CL, Middleton WD, Teefey SA, McClennan BL (1996) Angiomyolipoma and renal cell carcinoma: US differentiation. Radiology 198(3):789–793

Sim JS, Seo CS, Kim SH et al (1999) Differentiation of small hyperechoic renal cell carcinoma from angiomyolipoma: computer-aided tissue echo quantification. J Ultrasound Med 18(4):261–264

Reuter VE, Presti JC Jr (2000) Contemporary approach to the classification of renal epithelial tumors. Semin Oncol 27(2):124–137

Funding

The authors state that this work has not received any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Guarantor

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Prof. Dirk-André Clevert.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare relationships with the following companies: Dirk-André Clevert declares that he received compensation as a speaker from the following companies: Samsung, Philips, Siemens, Bracco, and Falk.

The other authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.

Statistics and biometry

Dipl.-Stat. Regina Schinner (Department of Radiology, LMU Munich) kindly provided statistical advice for this manuscript. She is not an author of the manuscript.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was waived by the institutional review board.

Ethical approval

Institutional review board approval was obtained.

Methodology

• Retrospective

• diagnostic prognostic study

• performed at one institution

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rübenthaler, J., Negrão de Figueiredo, G., Mueller-Peltzer, K. et al. Evaluation of renal lesions using contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS); a 10-year retrospective European single-centre analysis. Eur Radiol 28, 4542–4549 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-018-5504-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-018-5504-1