Abstract

Objectives

To assess the opinion on structured reporting (SR) and its usage by radiologist members of the Italian Society of Medical Radiology (SIRM) via an online survey.

Methods

All members received an email invitation to join the survey as an initiative by the SIRM Imaging Informatics Chapter. The survey included 10 questions about demographic information, definition of radiological SR, its usage in everyday practice, perceived advantages and disadvantages over conventional reporting and overall opinion about SR.

Results

1159 SIRM members participated in the survey. 40.3 % of respondents gave a correct definition of radiological SR, but as many as 56 % of them never used it at work. Compared with conventional reporting, the most appreciated advantages of SR were higher reproducibility (70.5 %), better interaction with referring clinicians (58.3 %) and the option to link metadata (36.7 %). Risk of excessive simplification (59.8 %), template rigidity (56.1 %) and poor user compliance (42.1 %) were the most significant disadvantages. Overall, most respondents (87.0 %) were in favour of the adoption of radiological SR.

Conclusions

Most radiologists were interested in radiological SR and in favour of its adoption. However, concerns about semantic, technical and professional issues limited its diffusion in real working life, encouraging efforts towards improved SR standardisation and engineering.

Key Points

• Despite radiologists’ awareness, radiological SR is little used in working practice.

• Perceived SR advantages are reproducibility, better clinico-radiological interaction and link to metadata.

• Perceived SR disadvantages are excessive simplification, template rigidity and poor user compliance.

• Improved standardisation and engineering may be helpful to boost SR diffusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last decade diagnostic imaging has seen a dramatic evolution driven by huge technological advancements. In particular, cross-sectional imaging modalities such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging have been revolutionised, with the current possibility to routinely acquire thousands of thin-slice images with voxel isotropy in a few seconds and to obtain a huge amount of morphological and functional information. Such evolution has, in turn, led to a broadening of the clinical indications of modern imaging techniques (favoured by their widespread diffusion even in peripheral centres), associated with a vast improvement in radiological knowledge and the development of validated recommendations and guidelines for the diagnostic management of several disease conditions [1, 2]. Furthermore, in recent years referring physicians and radiologists have shown increasing interest in a more standardised radiological report, i.e. a structured report, in line with the most up-to-date guidelines [3–6].

From a technical viewpoint, a structured report can be defined as a document consisting of a list of items and concepts with hierarchical relationships, including coded or numeric content in addition to plain text as well as embedded references to images and similar objects [7]. In other words, structured reporting (SR) relies on the usage of standardised templates depending on the diagnostic query, which form the semantic framework of a digital document made up of an ordered series of fields, each containing predefined kinds of information (e.g. numeric, alphabetical, Boolean or metadata such as key images, movies or Web links). In this way, SR may reduce the ambiguity of natural language format reports and enhance the precision, clarity and value of clinical documents [3]. Moreover, the digital nature of SR allows one to fully tap the processing, archiving and sharing capabilities of workstations and networks over which such data are circulated. In the case of radiological SR as well as some non-radiological applications (e.g. interventional cardiology), SR documents could be encapsulated and saved in DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) format, yielding an efficient and universal environment for the distribution of information between the various specialties and over RIS/PACS platforms [3, 8–12].

In the literature there is increasing agreement that SR may improve workflow in the radiological as well as in the clinical routine by reducing variability across readers as well as reporting times compared with conventional reporting. Furthermore, SR was found to be more accepted by both radiologists and referring clinicians because it can improve communication between them by the use of a standard and common language [4–6, 13–16]. To harness the strengths of the connection with the logical structure and DICOM framework of DICOM-based radiological SR, seamless integration with existing workstations and RIS/PACS infrastructures is essential, and modern speech recognition software has been developed with embedded functions for automated populating of radiological SR [5, 17]. Furthermore, efforts have been made by major scientific societies to encourage SR use in daily radiological practice, including the use of standard templates by the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) and the joint RSNA/ESR Reporting Initiative aimed at translating RSNA templates into a variety of European languages [11, 18, 19]. However, despite its potential advantages, some authors have stated that SR may be problematic [20] or even inferior to conventional reporting [21] because of the difficulty in accurately conveying all the required information in templates in complex cases, advocating that generalised evidence from randomised controlled trials is required before large-scale promotion [22]. As a matter of fact, SR has only gained modest overall acceptance among radiologists [5, 23]; to our knowledge, no consistent data have been published so far on SR usage by radiologists on a nationwide level.

Our purpose was therefore to collect the opinion on radiological SR and assess its usage by radiologist members of the Italian Society of Medical Radiology (SIRM) via a dedicated online survey.

Materials and methods

The online survey was launched as part of an initiative by the Imaging Informatics Chapter of SIRM aimed at promoting the development of a set of validated SR models integrated into existing RIS/PACS infrastructures, to be implemented in collaboration with other scientific chapters of SIRM and a number of IT firms with experience in the field. The purpose of the survey was to assess the degree of knowledge of radiological SR and its usage by radiologists in their daily practice.

Four radiologists of the Imaging Informatics Chapter of SIRM (D.R., F.C., L.F., R.F.) created the online survey using the SurveyMonkey platform (www.surveymonkey.com). The survey was compiled following suggestions from a multidisciplinary expert panel of SIRM and comprised 10 questions, six of which were single choice and four multiple choice (Table 1). One question (no. 9) also included a free text field for comments (Appendix).

All participants were radiologist members of SIRM who had been invited to the questionnaire via an email sent by the President of the Imaging Informatics Chapter (D.R.) containing a private Web link to the survey. The latter could be accessed only once by each user and remained open for a time period of 9 days. A reminder was emailed to all participants 1 day before the survey’s closure.

Data were analysed quantitatively using the SurveyMonkey Statistical Tool (www.surveymonkey.com) and dedicated software for statistical analysis (GraphPad Prism v. 7, www.graphpad.com). The correlation between age class (as determined by question 2) and rate of survey respondents supporting (either strongly or partly) the adoption of radiological SR (question 10) was assessed using the Spearman rank test. Furthermore, the association between demographic characteristics other than age (i.e. geographic distribution, workplace and job position, as determined by questions 1, 3 and 4, respectively) and rate of radiological SR supporters (question 10) was evaluated using the Chi-square test. A p value less than 0.05 was set as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

A total of 1159 SIRM members in full standing for the year 2015 took part in the survey with quite a homogeneous distribution in the various Italian regions relative to the number of members per region (question 1). The age distribution of the survey participants was quite homogenous as well, showing two peaks in the 36–45 and the 56–65 years old ranges [25.5 % (291/1140) and 26.6 % (303/1140), respectively] (question 2) (Fig. 1).

More than 50 % of respondents worked in public hospitals, and a relevant fraction of them [28.4 % (325/1143)] operated privately (question 3). In absolute terms, most respondents worked as basic level professional assistant medical directors [26.3 % (301/1143)] or consultants [23.5 % (269/1143)] (question 4) (Fig. 2).

Most participants were able to give a correct definition of radiological SR [40.3 % (457/1133)] (question 5), whereas 31.2 % (354/1133) gave a less correct, but still plausible reply. All other respondents showed lack of basic knowledge of radiological SR, and out of them, 19.1 % (217/1133) revealed confusion between the concepts of template and SR. As to the typical usage of radiological SR by the survey participants (question 6), none [56.3 % (643/1142)] or less than 50 % of their colleagues [21.8 % (249/1142)] reportedly used it, with only 9.7 % of respondents (111/1142) stating that SR was preferred by more than 50 % of their colleagues (Fig. 3).

Distribution of answers to question 5 (top) and question 6 (bottom). Answers from 1 to 4 (Q5) and 1 to 10 (Q6), respectively, are listed in Appendix

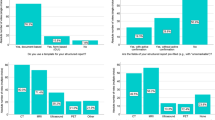

Questions 7 and 8 were aimed at assessing the perceived potential advantages and disadvantages of radiological SR compared with conventional reporting, respectively. The most appreciated advantages of SR were higher reproducibility of reporting with the possibility to adhere to validated classifications and guidelines [70.5 % (799/1143)], better interaction between radiologists and referring clinicians [58.3 % (661/1143)] and the option to add key images and other metadata to the report [36.7 % (416/1143)]. On the other hand, the potential perceived disadvantages of SR included the risk of excessively simplified reporting in complex cases [59.8 % (676/1130)], excessive rigidity of reporting templates [56.1 % (634/1130)] and poor compliance by most radiologists used to conveying information by means of conventional reporting [42.1 % (476/1130)] (Fig. 4).

Distribution of answers to question 7 (top) and question 8 (bottom). Answers from 1 to 8 (Q7) and 1 to 6 (Q8), respectively, are listed in Appendix

Question 9 tackled several issues regarding the use of radiological SR in daily radiological practice and its implementation in existing infrastructure (Fig. 5), whereas question 10 aimed to assess the survey participants’ overall opinion on radiological SR. Of note, 80.7 % of respondents to question 9 (889/1101) agreed that improved RIS/PACS integration would play a significant role in making the use of radiological SR more widespread and accepted by radiologists, while 72.3 % (806/1114) and 53.0 % (580/1094) strongly agreed that the inclusion of free text parts and fields related to the imaging technique in radiological SR templates, respectively, would be additional welcome features. Moreover, 75.7 % of respondents (824/1088) respondents agreed that radiological SR should be explicit even in case of unremarkable examinations, while according to 46.4 % of them (492/1061), non-radiologist specialists should be allowed to have a role in the reporting process.

Distribution of answers to question 9 [top; items 1–6 are listed in Appendix (Q9)] and overall opinions about radiological SR (bottom)

Overall, 30.0 % of respondents (342/1141) strongly supported and 57.1 % (651/1141) moderately supported radiological SR, respectively, whereas only 7.4 % (84/1141) were against it. No statistically significant correlation was found between survey respondents’ age and rate of radiological SR supporters (r s = −0.1, p > 0.05). Likewise, no statistically significant association was found between the latter on the one hand and geographic distribution, workplace and job position on the other hand (all p > 0.05).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first Italian survey on radiological SR addressed to radiologists on a nationwide level, as well as the first survey on this topic involving members of a national radiological society in Europe.

A rather small fraction of SIRM members participated in the survey [12.1 % (1159/9560)], yet this participation rate was on the same order of magnitude as an online survey on teleradiology conducted on SIRM members using the same methods [16.5 % (1599/9662)] [24], and much higher compared with a similar European online survey on teleradiology conducted by Ranschaert et al. (368 radiology professionals from 35 European countries) [25]. Moreover, the age and geographic distribution of the survey participants were fairly homogeneous with the partial exception of the lowermost and uppermost age classes (25–35 and over 65 years old, respectively), and the response rate for each survey question exceeded 95 % for all questions, revealing a general interest in the topic of radiological SR across several generations of radiologists.

The timeliness of the issue of radiological SR among the survey participants was confirmed by their average knowledge of its basic features, as shown by the high rate of right answers to question 5 (definition of radiological SR). Moreover, it is notable that the advantages of radiological SR over conventional reporting as outlined by respondents (question 7) are largely in line with the current literature, including better report reproducibility (70.5 %), improved communication between radiologists and referring clinicians (58.3 %) and more concise reporting (43.0 %) as main strengths [4, 9, 26]. This can be interpreted both as a proof of good knowledge of the potential implications of radiological SR by the survey participants and as a confirmation of previously published data [4, 5, 14]. In particular, in the paper by Schwartz et al., radiologists and referring clinicians found that SR had better content and greater clarity than conventional reports [4], while the implementation of standardised department-wide SR was shown to gain radiologists’ favour with an adoption rate near 100 % [5].

Strikingly and seemingly in contrast with the above findings, the replies to question 6 (current usage of SR at the participant’s working site) showed that in the majority of cases radiological SR was not used at all (56.3 %) or used by less than 50 % of the radiological staff (21.8 %). This de facto reluctance to leave conventional reporting for SR adoption in radiological daily practice may be explained by the perceived disadvantages and current limitations of radiological SR as highlighted by replies to questions 8 and 9. In particular, the main perceived weaknesses of SR compared with conventional reporting are represented by excessive report simplification in complex cases (59.8 % of respondents to question 8) and excessive rigidity of reporting templates (56.1 %), which would assumedly be avoided using “constraint-free” conventional reporting and were deemed as major weaknesses of radiological SR in the work by Johnson et al., conducted using earlier SR technology [27, 28]. Such concern was also expressed quite extensively by participants in free text comments and came along with some radiologists’ fear of losing their autonomy or even (as stated by some commenters) their professional reputation with respect to patients or non-radiologist specialists. This latter position might partially be explained by the fact that some radiologists with high subspecialty skills are worried about losing some of their professional authoritativeness once effective, validated SR covering their area of interest would be made available to the radiological community. Besides, it should be acknowledged that currently, widespread implementation of radiological SR still has significant drawbacks in more complex cases [20] and/or conditions where subjective scoring allows one to better assess pathological findings (such as reported by Vaché et al., who found that subjective scoring of prostate magnetic resonance examinations by experienced readers resulted in more accurate characterisation of the likelihood of malignancy than two different semiobjective scores did [21, 22]).

As a matter of fact, it is acknowledged that accuracy, clarity, completeness and timeliness are all essential features of radiological reporting (even in the case of unremarkable examinations) [27], and the acceptance of report standardisation by radiologists is key for successful implementation of SR programs [5, 10, 29]. To this end, specific suggestions to enhance the adoption of radiological SR were given by the survey participants, including better integration with existing RIS/PACS systems, the possibility to retain some free text fields within templates (thus leaving some margin to express complex concepts or descriptions in selected cases), as well as information related to the imaging protocol (especially in the case of modalities involving exposure to ionising radiation, such as CT). While this latter issue has been recognised to be of paramount importance to aid protocol optimisation and auditing procedures, spurring the development of DICOM-compliant monitoring tools with PACS integration [30, 31], the requirements for successful practical implementation of radiological SR indicated by the survey participants seem to reflect a perceived inadequacy of the currently available technical infrastructure that actually prevents a more widespread adoption of it. In line with this interpretation, only 12.5 % of respondents to question 7 mentioned higher radiologist productivity as a potential advantage of radiological SR over conventional reporting, yet as many as 81.1 % agreed that radiological SR is going to see further development in the future (question 9).

The main limitation of our study is the relatively small fraction (12.1 %) of SIRM members taking part in our survey, which might be not representative of the entire population of SIRM members. This same limitation was encountered in other similar studies [24, 25] and may have led to a selection bias due to a possibly higher prevalence of survey participants with more interest in the topic of radiological SR, better knowledge of it, and perhaps greater IT skills than the majority of SIRM members who did not join the survey. In respect to the last of these points, the lack of an additional question in the survey about the perceived familiarity of each respondent with IT tools might be a further limitation, since this might have prevented us from finding some correlation between IT skills on the one hand and knowledge of SR and overall opinion about it on the other hand.

Conclusions

Our findings show that the majority of radiologists involved in the survey are overall interested in the topic of radiological SR and, to a variable extent, open to the possibility of its adoption in their daily practice. However, such expectations appear to be influenced by concerns related to semantic (such as definition, standardisation and validation of templates), technical (e.g. SR implementation in the radiological environment and integration with existing RIS/PACS networks) and professional issues (including the perception of the radiologist’s role by referring clinicians and patients), resulting in a wide heterogeneity of views and a limited diffusion of radiological SR in real working life so far. We believe that such hurdles to a more widespread adoption of radiological SR can at least partly be overcome by the standardisation and validation of templates with the endorsement of scientific societies, paralleled by a close collaboration between medical institutions and the industry for engineering and technical setup, as well as by continuous feedback from the radiological and clinical community for auditing of quality, communication efficiency and overall user satisfaction.

References

Kalender WA, Quick HH (2011) Recent advances in medical physics. Eur Radiol 21:501–504

Thrall JH (2014) Appropriateness and imaging utilization: "computerized provider order entry and decision support". Acad Radiol 21:1083–1087

Hussein R, Engelmann U, Schroeter A, Meinzer HP (2004) DICOM structured reporting: Part 2. Problems and challenges in implementation for PACS workstations. Radiographics 24:897–909

Schwartz LH, Panicek DM, Berk AR, Li Y, Hricak H (2011) Improving communication of diagnostic radiology findings through structured reporting. Radiology 260:174–181

Larson DB, Towbin AJ, Pryor RM, Donnelly LF (2013) Improving consistency in radiology reporting through the use of department-wide standardized structured reporting. Radiology 267:240–250

Brook OR, Brook A, Vollmer CM, Kent TS, Sanchez N, Pedrosa I (2015) Structured reporting of multiphasic CT for pancreatic cancer: potential effect on staging and surgical planning. Radiology 274:464–472

Clunie DA (2000) DICOM structured reporting. PixelMed, Bangor

Kahn CE Jr, Langlotz CP, Burnside ES et al (2009) Toward best practices in radiology reporting. Radiology 252:852–856

Noumeir R (2006) Benefits of the DICOM structured report. J Digit Imaging 19:295–306

Bosmans JM, Peremans L, Menni M, De Schepper AM, Duyck PO, Parizel PM (2012) Structured reporting: if, why, when, how-and at what expense? Results of a focus group meeting of radiology professionals from eight countries. Insights Imaging 3:295–302

Bosmans JM, Neri E, Ratib O, Kahn CE Jr (2015) Structured reporting: a fusion reactor hungry for fuel. Insights Imaging 6:129–132

Margolies LR, Pandey G, Horowitz ER, Mendelson DS (2016) Breast imaging in the era of big data: structured reporting and data mining. AJR Am J Roentgenol 206:259–264

Karim S, Fegeler C, Boeckler D, H Schwartz L, Kauczor HU, von Tengg-Kobligk H (2013) Development, implementation, and evaluation of a structured reporting web tool for abdominal aortic aneurysms. JMIR Res Protoc 2, e30

Barbosa F, Maciel LM, Vieira EM, Azevedo Marques PM, Elias J, Muglia VF (2010) Radiological reports: a comparison between the transmission efficiency of information in free text and in structured reports. Clinics 65:15–21

Marcovici PA, Taylor GA (2014) Journal Club: structured radiology reports are more complete and more effective than unstructured reports. AJR Am J Roentgenol 203:1265–1271

Durack JC (2014) The value proposition of structured reporting in interventional radiology. AJR Am J Roentgenol 203:734–738

Weiss DL, Langlotz CP (2008) Structured reporting: patient care enhancement or productivity nightmare? Radiology 249:739–747

RadLex (2016) https://www.radlex.org. Accessed 11 Jun 2016

European Society of Radiology (2013) ESR communication guidelines for radiologists. Insights Imaging 4:143–146

Baron RL (2014) The radiologist as interpreter and translator. Radiology 272:4–8

Vaché T, Bratan F, Mège-Lechevallier F, Roche S, Rabilloud M, Rouvière O (2014) Characterization of prostate lesions as benign or malignant at multiparametric MR imaging: comparison of three scoring systems in patients treated with radical prostatectomy. Radiology 272:446–455

Winter TC (2015) The propaedeutics of structured reporting. Radiology 275:309–310

Reiner BI (2012) Optimizing technology development and adoption in medical imaging using the principles of innovation diffusion, part II: practical applications. J Digit Imaging 25:7–10

Coppola F, Bibbolino C, Grassi R et al (2016) Results of an Italian survey on teleradiology. Radiol Med. doi:10.1007/s11547-016-0640-7

Ranschaert ER, Binkhuysen FH (2013) European teleradiology now and in the future: results of an online survey. Insights Imaging 4:93–102

Travis AR, Sevenster M, Ganesh R, Peters JF, Chang PJ (2014) Preferences for structured reporting of measurement data: an institutional survey of medical oncologists, oncology registrars, and radiologists. Acad Radiol 21:785–796

Johnson AJ, Chen MY, Swan JS, Applegate KE, Littenberg B (2009) Cohort study of structured reporting compared with conventional dictation. Radiology 253:74–80

Langlotz CP (2009) Structured radiology reporting: are we there yet? Radiology 253:23–25

Sistrom CL, Langlotz CP (2005) A framework for improving radiology reporting. J Am Coll Radiol 2:159–167

Wang S, Pavlicek W, Roberts CC et al (2011) An automated DICOM database capable of arbitrary data mining (including radiation dose indicators) for quality monitoring. J Digit Imaging 24:223–233

Lauretti DL, Neri E, Faggioni L, Paolicchi F, Caramella D, Bartolozzi C (2015) Automated contrast medium monitoring system for computed tomography—intra-institutional audit. Comput Med Imaging Graph 46(Pt 2):209–218

Acknowledgments

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Prof. Daniele Regge, MD. The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article. The authors state that this work has not received any funding. No complex statistical methods were necessary for this paper. Institutional review board approval was not required because this paper shows the results of a survey and did not involve human or animal subjects. Methodology: online survey (multicentre study).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Faggioni, L., Coppola, F., Ferrari, R. et al. Usage of structured reporting in radiological practice: results from an Italian online survey. Eur Radiol 27, 1934–1943 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-016-4553-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-016-4553-6