Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate survival and outcomes after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of malignant renal tumours in high-risk patients with long-term follow-up.

Methods

Between 2002 and 2009, 62 patients (71 tumours), with a median age of 73.5 years (20–87), consecutively treated with RFA under ultrasound or computed tomography guidance for malignant renal tumours were retrospectively selected and prospectively followed until 2012, including 25 patients (40.3 %) with solitary kidney and 7 cystic cancers. Maximal tumour diameters were between 8 and 46 mm (median: 23 mm).

Results

Radiofrequency ablation was technically possible for all patients. Mean follow-up was 38.8 months (range: 18–78 months). Primary and secondary technique effectiveness was 95.2 % and 98.4 % per patient respectively. The rates of local tumour progression and metastatic evolution were 3.2 % and 9.7 % per patient and were associated with tumour size >4 cm (P = 0.005). The disease-free survival rates were 88.3 % and 61.9 % at 3 and 5 years. No significant difference in glomerular filtration rates before and after the procedure was observed (P = 0.107). The major complications rate was 5.9 % per session with an increased risk in the case of central locations (P = 0.006).

Conclusions

Percutaneous renal RFA appears to be safe and effective with useful nephron-sparing results.

Key Points

• Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is a well-tolerated technique according to mid-term results.

• RFA for malignant renal tumours preserved renal function in high-risk patients.

• Mid-term efficacy of RFA was close to that of formal conservative surgery.

• Tumour size and central location limit the efficacy and safety of RFA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Owing to the increasing use of radiological explorations, nearly 50 % of kidney cancers are now diagnosed incidentally [1], at a non-metastatic stage in 70 to 80 % of cases [2, 3]. For these reasons, conservative surgery has been developed largely as an alternative to total nephrectomy, to preserve renal function as long as possible [4].

However, some small kidney cancer patients are poor surgical candidates, such as in cases of advanced physiological age, associated comorbidities, or moderate renal failure. Therefore, for this highly selected group of patients who are at such high risk of morbidity and mortality in case of surgical management [5], alternative minimally invasive approaches such as percutaneous thermal ablation have been proposed [6].

Advantages of ablative therapies over partial nephrectomy include potential application in a wider patient population—including those who are poor surgical candidates—and an anticipated morbidity and mortality reduction. After promising preclinical results on kidney tumoors [7], data in the literature on clinical applications of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of renal cancers are growing and have confirmed the efficacy of the technique for renal cancers smaller than 4 cm [8–11]. However, compared with surgical series, most of these studies report short-term results, with less than 2 years’ follow-up [9–11].

The purpose of the current study is to evaluate survival and outcomes after percutaneous RFA of malignant renal tumours in high-risk patients with long-term follow-up for up to 10 years after treatment.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

This retrospective single-institution study was approved by the institutional review board; requirement for informed consent was waived. The institutional prospectively maintained radiological database was searched retrospectively for all cases of RFA performed for T1a malignant renal lesions at our institution from November 2002 to December 2009 (Fig. 1). A subset analysis was conducted by two genitourinary radiologists (P.B. and F.C., with 1 and 5 years’ experience respectively) on the results of the first data set to select only patients with no metastasis, progressive disease, venous extension, or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Patients in palliative situations or with Van Hippel Lindau (VHL) disease were also excluded. Renal tumours without available histopathological analysis were excluded for survival analysis while pathological confirmation was required for solid tumours only. Finally, a total of 62 patients, with 71 malignant renal tumours were included, including 25 patients (40.3 %) with solitary kidney and 7 cystic cancers.

Thermal ablation procedures

All patients were hospitalised for the procedure. The choice of RFA technique, of the appropriate applicator, and of ancillary techniques was at the discretion of each interventional radiologist according to his/her own experience and according to several tumour features, including tumour size, morphology and location, the proximity of adjacent structures, and the access route. Most procedures were performed using expandable needle systems (Le-Veen®, Boston Scientific Corporate, Natick, MA, USA; Angiodynamics, Queensbury, NY, USA). Water dissection was performed in 15 sessions, dissection with CO2 in 1, and pyeloperfusion in 14. Prophylactic antibiotics were systematically prescribed before each procedure (cefotaxime 2 g IV).

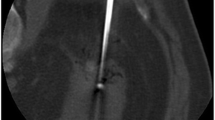

For all patients, RFA procedures were performed percutaneously, under ultrasound guidance for two patients and under computed tomography (CT) guidance (SOMATOM Sensation 16, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) for all others (Fig. 2). General anaesthesia was given to all patients. In each case, vital signs were continuously monitored by an anaesthetist and a dedicated nurse. All patients were observed for a minimum of 3 h following the procedure.

Renal function was monitored in all cases before the procedure and 2 and 6 months after the procedure by measuring serum creatinine and calculating creatinine clearance with the Modification of the Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula.

Follow-up imaging

All patients received follow-up using either contrast-enhanced CT or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, depending on their renal function. These included an early control study 2–3 months after ablation for evaluation of the technical effectiveness and detection of complications, then subsequently at 6 months, 1 year, and at 1-year intervals thereafter, to assess the local efficacy and the absence of local tumour progression. A prospective collection of imaging and clinical follow-up continued until the end of August 2012 for all patients. The diagnosis of complete tumour necrosis was based on the absence of any enhancement within the ablated zone. Enhancement was considered significant when greater than 15 HU on CT (Fig. 3) and 15 % on MRI on the follow-up examinations. Absence of any enhancement on initial 2- to 3-month follow-up imaging was considered a technical success. Absence of enhancement on initial follow-up imaging was considered a complete ablation (for evaluation of primary treatment failure), and enhancement or enlargement of the ablation area on subsequent imaging after an initially negative imaging study was considered to show local tumour recurrence.

Data collection and statistical analysis

All data relating to the treated patients were compiled on the basis of a review of all medical, biological, imaging, and biopsy reports by one of the authors (P.B.). All images were retrospectively reviewed independently by two board-certified radiologists (P.B. and F.C.). Data were entered into a worksheet for storage (Excel; Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). The primary study endpoints were overall survival for each patient and time to recurrence for an individual tumour. Overall survival was defined as the time from the first RFA to death of any cause or last date of follow-up. The survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to assess overall survival differences between groups for the univariate analysis. Procedure-related complications and side effects were noted and classified on the basis of criteria proposed by the Society of Interventional Radiology [12] and the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Events (CTCAE, version 4.0). The relative significance of the variables in predicting survival, recurrence, or complications was assessed using multivariate Cox regression analysis. All statistical tests were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software Windows 9.2.

Results

Patient group

There were 48 male and 14 female patients, ranging in age from 20 to 87 years (median 73.5 years; Table 1). Among the 62 patients (71 tumours), 8 had two tumours and 2 had three (Table 2). Seven tumours were type 4 cystic tumours according to the Bosniak classification of cystic masses [13]. For patients with solid tumours, 30 presented with clear cell carcinomas (CCC), 12 with papillary carcinomas, and 3 with chromophobe carcinomas. The 10 patients with pathologically proven renal cell carcinomas (RCC), but without identified tumour subtype, were also treated.

Procedural information

Primary technical success was observed for 95.2 % of patients (Fig. 2) with only three residual unablated tumour segments (tumour sizes of 40, 43 and 46 mm) on the first imaging study following RFA. Two of these were retreated successfully with RFA, providing a secondary technical success of RFA of 98.4 %.

Outcomes

Mean follow-up was 38.8 months (SD: 18.5 months) with a median of 36.5 months (ranging from 18 to 78 months). Ten patients (16.1 %) died during the course of follow-up: one because of thermal injury of the duodenum and perforation 1 week after the procedure; seven died because of other co-morbidities, and two patients died because of renal neoplastic disease progression. The specific survival rate was 96.8 % and the metastatic disease-free survival was 93.5 %. Median survival and overall survival were 68 months and 90.1 % respectively for tumours less than 3 cm, and 55 months and 44.0 % respectively for tumours larger than 3 cm (P = 0.03; Fig. 3). The overall survival rate was 82.3 % (95 % CI = 0.650–0.915) and 60.9 % (95 % CI = 0.29–0.820) at 3 and 5 years, respectively (Fig. 3).

Nine recurrences were observed: two in situ recurrences for initial tumours larger than 3 cm with central locations (one associated with pulmonary metastasis at 1 year and one at 2 years; Fig. 4); two ipsilateral recurrences outside the ablative site (1 at 2 years, adequately treated with a new RFA session, and 1 at 3 years); two contralateral recurrences at 3 and 4 years; and four metachronous distant recurrences (but one associated with an in situ recurrence). The rates of local tumour progression and metastatic evolution were respectively 3.2 % and 9.7 % per patient. Therefore, the rate of local recurrence at the ablative site, after exclusion of the three incomplete initial RFAs, was 1.6 % (1/62). The secondary technical success rate of RFA including treatment of recurrences was 96.7 %.

a Axial enhanced CT shows a 34-mm central renal clear cell carcinoma in a 77-year-old patient. The lesion was treated with an expandable needle system. b, c, d Axial CT before and after contrast medium injection performed 1 year after radiofrequency ablation (RFA) shows contrast enhancement (arrows) during arterial (30-s) (c) and tubular (90-s) phases (d), compared with acquisition without contrast medium (b). This was considered as an in situ recurrence on the central side of the lesion. Cryoablation was successfully performed

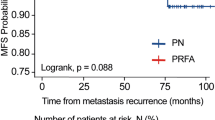

Overall disease-free survival rate at 3 years was 88.3 % (95 % CI = 0.750 to 0.948) and 61.9 % (95 % CI = 0.313–0.820) at 5 years (Fig. 5).

a Recurrence-free survival for the population selected. Overall disease-free survival rate was 88.3 % (95 % CI = 0.750–0.948) and 61.9 % (95 % CI = 0.313–0.820) at 3 and 5 years, respectively. b Recurrence-free survival rate for tumours less than 4 cm and tumours larger than 4 cm: 100 % of tumours <4 cm were completely processed from the first RFA while only 4 of the tumours >4 cm had a complete initial treatment (57.1 %)

In univariate analysis, central location appeared to be a risk factor for recurrence with a relative risk (RR) of 22.41 (95 % CI = 2.48 to 202.38, P = 0.006). In univariate and multivariate analysis, size was the only factor independently associated with the occurrence of residual tumour or in situ recurrence. Of tumours less than 4 cm, 100 % were completely processed from the first RFA while only four of the tumours greater than 4 cm (57.1 %) had a complete initial treatment. For a 1-cm increase the relative risk was 9.35 (95 % CI = 2.08 to 41.43; P = 0.005; Fig. 5).

Complications and effects on renal function

Hospitalisation duration was less than 3 days for 44 patients (47 %) with a mean hospital stay of 4.29 days (range: 2–13). Mean creatinine clearance before the procedure was 61.3 ml/min (SD = 22.9 ml/min), and 58.6 ml/min (SD = 25.1 ml/min; P = 0.367) and 60.6 ml/min (SD = 24.8 ml/min; P = 0.107) at 2 and 6 months respectively. Four (4.3 %) major early complications occurred (Table 3). Five patients presented severe late complications after treatment of central tumours. The overall major complications rate per patient was 5.9 %. In multivariate analysis, only a central location of the tumour was associated with an increased risk of complications (odds ratio: 22.66, 95 % CI = 2.47 to 208.33, P = 0.006).

Discussion

These medium-term results of RFA performed over 10 years in our institution confirm that this ablative method could be an attractive alternative option for the management of small malignant renal tumours, even in poor surgical candidates, irrespective of the reasons. For these patients, renal tumours were adequately controlled with this local treatment with an overall disease-free survival rate of 88.3 % at 3 years and 61.9 % at 5 years. This observation was concordant with data from the literature [14]. Additionally, our results have shown that an additional RFA session was not a technical challenge after a first session of RFA in the case of unablated tumours. Therefore, the secondary efficacy rate of RFA, which is more informative and representative of the contribution of the technique in terms of oncological control [12], was close to conservative surgery results [15], with a rate of 98.4 %. It was in accordance with the 90–100 % reported in the literature [14, 16–19].

Moreover, as reported in previous studies, the complications rate was low. The major complications rate was 5.9 %, close to values found in the literature on the topic ranging from 0 to 6 % [16, 20] and close to the data observed with open partial nephrectomy, which were 6.3 % (4.5–8.7 %) [21], mainly represented by urinary fistulas (4.1 %). As reported in our study, severe complications may occur after renal RFA, such as injuries to the bowel (colon or duodenum), either as a result of inadvertent puncture or by extension of the ablation zone [22]. To avoid these complications, thermal protection techniques have been proposed [23, 24] in addition to an optimisation of the position of the probes with the expanded use of multiplanar reconstructions. However, one of the main advantages of RFA compared with nephrectomy was the absence of any detectable renal function impairment after treatment, as reported previously [25, 26] even in solitary kidneys [27]. Our study confirmed this observation without a significant decrease in renal function reported at 2 and 6 months for patients treated for a single tumour with RFA.

Nevertheless, our medium-term results also confirmed that it is important to consider several morphological factors before planning a percutaneous RFA in order to limit morbidity and failures. Size is actually one of the well-identified limits of RFA. Median survival and overall survival rates were greater for tumours ≤3 cm than for tumours >3 cm (P = 0.03). Moreover, in univariate and multivariate analysis, the size (threshold: 4 cm) was the only factor independently associated with the occurrence of residual tumour or in situ recurrence (P = 0.005). While several techniques have been proposed to increase the ablation volume of RFA, such as preoperative embolisation or anti-angiogenic drugs [28], prospective studies are still awaited. Furthermore, microwaves, which create larger ablation zones than RFA [29, 30], could also be useful in the future in these cases.

Our study also agrees with previous data [6] by considering the central location of the tumour as a risk of technical failure (P = 0.006) and complications (P = 0.006). The reasons are a delicate placement, a loss of the thermal impact of RFA due to the proximity of the vascular pedicles, the heat sink effect and the irrigation of the upper urinary tract. Cryoablation seems to be more efficient for this tumour location [8] and must be proposed in this case. On the other hand, with only one incomplete first RFA session of a 40-mm non-central tumour in our study, the exophytic location seems to be a predictive factor of therapeutic success because of the easier positioning of the RF electrode and the insulating effect of the peri-renal fat [16].

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective analysis performed over 10 years with its inherent limitations. Our data collection begins at the first procedure performed in our centre, implying an initial learning phase and a progressive adaptation of heating protocols. Second, our selected population, by its intrinsic characteristics, is itself a bias in the interpretation of results for comparison with the surgical technique. Third, the criterion for therapeutic efficacy is based on imaging, which remains the gold standard because of its accessibility and its non-invasive nature; systematic biopsies after RFA do not appear justified without incomplete treatment being suspected on imaging follow-up [14].

In conclusion, according to these medium-term results, we can assume that percutaneous RFA is safe and effective in treating primary renal cell carcinomas, with a low morbidity for exophytic or parenchymal tumours. This minimally invasive therapeutic option contributes to the conservation of renal function and subsequently to the improvement of quality of life and life expectancy of patients even in cases of poor surgical candidates. Nevertheless, longer term imaging follow-up on large cohorts remains necessary.

Abbreviations

- GE:

-

Gradient echo

- Gd:

-

Gadolinium

- RCC:

-

Renal cell carcinoma

- CCC:

-

Clear cell carcinoma

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- RFA:

-

Radiofrequency ablation

References

Jayson M, Sanders H (1998) Increased incidence of serendipitously discovered renal cell carcinoma. Urology 51:203–205

Bosniak MA, Birnbaum BA, Krinsky GA, Waisman J (1995) Small renal parenchymal neoplasms: further observations on growth. Radiology 197:589–597

Homma Y, Kawabe K, Kitamura T et al (1995) Increased incidental detection and reduced mortality in renal cancer–recent retrospective analysis at eight institutions. Int J Urol 2:77–80

Bird VG, Carey RI, Ayyathurai R, Bird VY (2009) Management of renal masses with laparoscopic-guided radiofrequency ablation versus laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. J Endourol/Endourol Soc 23:81–88

Boyd O, Jackson N (2005) How is risk defined in high-risk surgical patient management? Crit Care 9:390–396

Kunkle DA, Uzzo RG (2008) Cryoablation or radiofrequency ablation of the small renal mass: a meta-analysis. Cancer 113:2671–2680

Miao Y, Ni Y, Bosmans H et al (2001) Radiofrequency ablation for eradication of renal tumor in a rabbit model by using a cooled-tip electrode technique. Ann Surg Oncol 8:651–657

Cornelis F, Balageas P, Le Bras Y, et al (2012) Radiologically-guided thermal ablation of renal tumours. Diagn Interv Imaging

Li-M S, Jarrett TW, Chan DY, Kavoussi LR, Solomon SB (2003) Percutaneous computed tomography-guided radiofrequency ablation of renal masses in high surgical risk patients: preliminary results. Urology 61:26–33

Farrell MA, Charboneau WJ, DiMarco DS et al (2003) Imaging-guided radiofrequency ablation of solid renal tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 180:1509–1513

Mayo-Smith WW, Dupuy DE, Parikh PM, Pezzullo JA, Cronan JJ (2003) Imaging-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of solid renal masses: techniques and outcomes of 38 treatment sessions in 32 consecutive patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 180:1503–1508

Goldberg SN, Grassi CJ, Cardella JF et al (2005) Image-guided tumor ablation: standardization of terminology and reporting criteria. J Vasc Interv Radiol 16:765–778

Bosniak MA (1997) Diagnosis and management of patients with complicated cystic lesions of the kidney. AJR 169:819–821

Tracy CR, Raman JD, Donnally C, Trimmer CK, Cadeddu JA (2010) Durable oncologic outcomes after radiofrequency ablation: experience from treating 243 small renal masses over 7.5 years. Cancer 116:3135–3142

Stern JM, Svatek R, Park S et al (2007) Intermediate comparison of partial nephrectomy and radiofrequency ablation for clinical T1a renal tumours. BJU Int 100:287–290

Gervais DA, Arellano RS, McGovern FJ, McDougal WS, Mueller PR (2005) Radiofrequency ablation of renal cell carcinoma: part 2, Lessons learned with ablation of 100 tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 185:72–80

Veltri A, Garetto I, Pagano E, Tosetti I, Sacchetto P, Fava C (2009) Percutaneous RF thermal ablation of renal tumors: is US guidance really less favorable than other imaging guidance techniques? Cardiovasc Interv Radiol 32:76–85

Levinson AW, Su L-M, Agarwal D et al (2008) Long-term oncological and overall outcomes of percutaneous radio frequency ablation in high risk surgical patients with a solitary small renal mass. J Urol 180:499–504

Salagierski M, Salagierski M, Salagierska-Barwinska A, Sosnowski M (2006) Percutaneous ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation for kidney tumors in patients with surgical risk. Int J Urol 13:1375–1379

Hiraoka K, Kawauchi A, Nakamura T, Soh J, Mikami K, Miki T (2009) Radiofrequency ablation for renal tumors: our experience. Int J Urol 16:869–873

Hui GC, Tuncali K, Tatli S, Morrison PR, Silverman SG (2008) Comparison of percutaneous and surgical approaches to renal tumor ablation: metaanalysis of effectiveness and complication rates. J Vasc Interv Radiol 19:1311–1320

Uppot RN, Silverman SG, Zagoria RJ, Tuncali K, Childs DD, Gervais DA (2009) Imaging-guided percutaneous ablation of renal cell carcinoma: a primer of how we do it. AJR Am J Roentgenol 192:1558–1570

Buy X, Tok CH, Szwarc D, Bierry G, Gangi A (2009) Thermal protection during percutaneous thermal ablation procedures: interest of carbon dioxide dissection and temperature monitoring. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol 32:529–534

Tsoumakidou G, Buy X, Garnon J, Enescu J, Gangi A (2011) Percutaneous thermal ablation: how to protect the surrounding organs. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol 14:170–176

Salas N, Ramanathan R, Dummett S, Leveillee RJ (2010) Results of radiofrequency kidney tumor ablation: renal function preservation and oncologic efficacy. World J Urol 28:583–591

Pettus JA, Werle DM, Saunders W et al (2010) Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation does not affect glomerular filtration rate. J Endourol 24:1687–1691

Cornelis F, Buy X, Andre M et al (2011) De novo renal tumors arising in kidney transplants: midterm outcome after percutaneous thermal ablation. Radiology 260:900–907

Hakime A, Hines-Peralta A, Peddi H et al (2007) Combination of radiofrequency ablation with antiangiogenic therapy for tumor ablation efficacy: study in mice. Radiology 244:464–470

Laeseke PF, Lee FT Jr, Sampson LA, van der Weide DW, Brace CL (2009) Microwave ablation versus radiofrequency ablation in the kidney: high-power triaxial antennas create larger ablation zones than similarly sized internally cooled electrodes. J Vasc Interv Radiol 20:1224–1229

Bartoletti R, Cai T, Tosoratti N et al (2010) In vivo microwave-induced porcine kidney thermoablation: results and perspectives from a pilot study of a new probe. BJU Int 106:1817–1821

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pippa McKelvie-Sebileau for medical editorial assistance in English.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Balageas, P., Cornelis, F., Le Bras, Y. et al. Ten-year experience of percutaneous image-guided radiofrequency ablation of malignant renal tumours in high-risk patients. Eur Radiol 23, 1925–1932 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-013-2784-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-013-2784-3