Abstract

The 27 species of the genus Pogonophryne are a distinctive component of the radiation of cryonotothenioid fishes and commonly encountered during benthic trawling and commercial longlining for toothfish. They are difficult to identify because they are morphologically and ecologically similar and sympatric in their distributions. The genus has recently been the subject of a taxonomic consolidation that, on the basis of nuclear gene sequence data and morphometrics, has synonymized the 27 species to the five known species groups and detected an unnamed sixth clade, decreasing the diversity of Pogonophryne by ≈ 78% and that of the radiation of cryonotothenioids by ≈ 16%. We clarify this situation by assigning each of the 27 species to a species group. We also provide an uncomplicated illustrated guide that requires no counting or measuring of characters and facilitates the placement of each of the species into one of three categories, five species groups, and three subgroups within the genus. These are the essential steps in identifying a species of Pogonophryne whether following the traditional or reduced view of diversity. With the exception of the details concerning the undescribed species, this is the heretofore elusive synopsis of the genus that should remain stable into the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

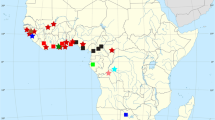

The 128 species of Antarctic cryonotothenioid fishes are one of the few well-documented examples of an adaptive radiation of fishes in the marine realm (Eastman and McCune 2000; Matschiner et al. 2015; Bowen et al. 2020). The genus Pogonophryne Regan 1914 (Artedidraconidae) is a component of that radiation, and the species are a ubiquitous benthic element of the shelf and upper slope waters of Antarctica (Eakin 1990; Hanchet et al. 2013; La Mesa et al. 2019). Over the past few decades the number of species has increased from 17 to 27, and Pogonophryne is now the most speciose genus of notothenioids (Eakin 1990; Eastman and Eakin 2021). They are medium-sized (predominantly 20–30 cm TL) sedentary benthic fishes found primarily at depths of 500–1600 m (Duhamel et al. 2014; Eastman 2017). Unlike many other cryonotothenioids, they exhibit minimal ecomorphological disparity and are a non-adaptive element of the radiation. They do, however, possess a mental barbel of uncertain functional significance. This structure is subject to intraspecific variation in some species (Eakin et al. 2001). With an age estimate of < 1 Ma, Pogonophryne is also the most recently diverged cryonotothenioid lineage (Near et al. 2012) and, because they exhibit a relatively low degree of interspecific morphological variation, this makes the species of Pogonophryne the most difficult-to-identify cryonotothenioids.

To facilitate identification and based on similarities in external morphology, the 27 species are allocated among three categories and five species groups within the categories (Table 1), with one species group containing three subgroups (Balushkin and Eakin 1998). These divisions, based strictly on morphology, have no taxonomic status, although all five species groups are clades based on mitochondrial gene sequences (Eakin et al. 2009). This has been confirmed by more extensive DNA sequencing that involved genome-wide data (ddRADseq) and morphometric analyses of the body shape axis by Parker et al. (2022), who also identified a previously unrecognized sixth clade. Based on their sample of 18 of the 27 species, Parker et al. propose reducing the number of species of Pogonophryne from 27 to 6 by synonymizing the species in each of the five species groups into a single species bearing the name of the species group. This results in a 78% reduction in the number of species. The newly recognized sixth species from the Ross Sea has not been formally described and named, and there is insufficient information for us to consider it here.

Because explaining diversity is a major focus in organismal biology, it is of general interest when an issue arises involving species diversity within a radiation. This is exemplified by Pogonophryne given that Parker et al. (2022, p. 58) state that their analyses “result in a dramatic reduction in the number of distinct species within” an Antarctic adaptive radiation. We also recognize that there has been taxonomic inflation within Pogonophryne. In the aftermath of the revisions of Parker et al. there will be uncertainty among those confronted with understanding the amalgamations, specifically how species should be identified and assigned to one of the five known species groups. Whether the traditional or the new reduced approach to the taxonomy of Pogonophryne is employed, the placement of a species in a category and then in a species group is the essential step in the identification process. Here we provide a table and an uncomplicated pictorial identification guide for Pogonophryne that dispels confusion by (1) delineating multiple features of external morphology, unrelated to barbel morphology, that define the categories and species groups and (2) identifying the species contained in each species group and subgroup.

Materials and methods

The initial step in the identification of an unknown species of Pogonophryne is the determination of its membership in a category and a species group (Table 1). This can be accomplished by utilizing features visible solely in the heads of species of each of the five groups. Although in Russian and not widely circulated, Figs. 2–5 in Andriashev’s (1967) review of the genus Pogonophryne are extremely useful for this purpose. The species groups were not yet recognized when he wrote the paper, but four of the five groups are represented in his figures. The fifth, or P. albipinna group, was subsequently recognized by Eakin (1981). It should also be noted that the P. scotti “group” consists of a single species.

Figures 2, 3, and 4 are scans of photographic copies of the original figures submitted for publication by Professor Anatole P. Andriashev (1967) for his paper reviewing the little-studied genus Pogonophryne. Andriashev gave photographic copies of his original illustrations to Professor Hugh DeWitt of the University of Maine who passed them on to his, then graduate student, Richard Eakin, and we are using them here. This is significant because these copies of the dorsal and lateral views of the head of P. mentella (Fig. 3c, d) show the large terminal expansion of the mental barbel as originally drawn by Andriashev’s artist. All known reprints and reproductions of this article contain a printing error that omitted the terminal expansion.

We used photographs of a specimen of P. immaculata to represent the P. albipinna species group because the holotype and only known specimen of P. albipinna is a 37.5 mm SL juvenile (Eakin 1981). The photographed P. immaculata in Fig. 1 was a freshly caught 209 mm SL female now preserved and catalogued in the collections of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (NMNZ P.043715).

Results and discussion

Categories, species groups, and subgroups of Pogonophryne

The guide is based on the pigmentation patterns, head shapes, and relative sizes of other features easily observed in dorsal or lateral views of the heads of Pogonophryne. The figures show the key features that distinguish categories and species groups: (1) the color pattern of the integument of the dorsal head, (2) the shape of the head, (3) the degree of projection of the lower jaw, (4) the relative volume of the orbit occupied by the eye, and (5) the relative size and shape of the mental barbel.

Each species of Pogonophryne can be assigned to one of three distinct categories (Table 1) based on easily observed differences in spotting patterns of the skin and other less obvious characters not considered here (Eakin 1977; 1981; 1990; Balushkin and Eakin 1998). The species in each category are further separable into five morphologically well-defined species groups (Balushkin and Eakin 1998). The validity of the species groups reflects consistent differences in color patterns, head shapes, jaw prognathism, mental barbel features, and meristic counts that distinguish species in each group, for example, numbers of vertebrae, lateral-line pores or scales, and certain fin rays. There has probably been over reliance on the importance of barbel morphology in some recent descriptions of new species of Pogonophryne, although among all species only the barbels of P. scotti exhibit documented intraspecific variation (Eakin et al. 2001). Parker et al. (2022, p. 71) indicate that their “results provide no genomic or phenotypic support for differentiation among species of Pogonophryne that are diagnosed exclusively using barbel morphology.” However the barbel has not been the sole character used in describing species. For example, six species of the P. mentella group (P. macropogon, P. cerebropogon, P. ventrimaculata, P. orangiensis, P. squamibarbata, and P. bellingshausenensis) are each defined by a unique combination of at least four characters: barbel length, terminal expansion morphology, spotting patterns, and vertebral counts (Eakin 1981, 1987; Eakin and Balushkin 1998, 2000; Eakin and Eastman 1998; Eakin et al. 2008).

Within the diverse P. mentella group there are three subgroups (Table 1) that contain 63% (17/27) of the species of Pogonophryne. These subgroups have no phylogenetic basis and are arbitrarily recognized based on the relative length of the mental barbels. However, arranging and categorizing the 17 species in this group by their barbel lengths facilitates their identifications as species. This does not imply that barbel morphology is the sole diagnostic character for these species, but rather that relative barbel lengths are useful in, for example, taxonomic key couplets (Eakin 1990, pp. 339–340). These subgroups are the focus of much of the consolidation suggested by Parker et al. (2022). Finally, we do not doubt the existence of a sixth lineage identified by Parker et al. and we urge future restraint in the description of new species of Pogonophryne without supporting nucleotide sequence data.

Faunal surveys of Antarctic fishes are now increasingly conducted using images obtained from towed high-resolution camera systems rather than by benthic trawling with its habitat-altering consequences. Although only a dorsal image of the fish is obtained in most survey photographs, it can usually be identified at the species level (Eastman et al. 2013; La Mesa et al. 2019). In addition to presence/absence data, these images also provide insight into other aspects of biology including reproductive behavior and have documented the universality of nesting and nest guarding behavior in cryonotothenioids, including Pogonophryne spp. (La Mesa et al. 2021). Although species identifications are difficult in Pogonophryne, our identification guide makes it possible to determine the species group membership using easily visible features in a dorsal image.

Data availability

Some specimens and data are deposited in the ichthyology collections of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, New Haven, CT USA.

Code availability

NA.

References

Andriashev AP (1967) A review of the plunderfishes of the genus Pogonophryne Regan (Pisces, Harpagiferidae) with descriptions of five new species from the East Antarctic and South Orkney Islands. Biol Results Sov Antarct Exped (1955–1958) 3:391–412

Balushkin AV, Eakin RR (1998) A new toad plunderfish Pogonophryne fusca sp. nova (Fam. Artedidraconidae: Notothenioidei) with notes on species composition and species groups in the genus Pogonophryne Regan. J Ichthyol 38:574–579

Bowen BW, Forsman ZH, Whitney JL, Faucci A, Hoban M, Canfield SJ, Johnston EC, Coleman RC, Copus JM, Vicente J, Toonen RJ (2020) Species radiations in the sea: what the flock? J Hered 111:70–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esz075

Duhamel G, Hulley P-A, Causse R, Koubbi P, Vacchi M, Pruvost P, Vigetta S, Irisson J-O, Mormède S, Belchier M, Dettai A, Detrich HW, Gutt J, Jones CD, Kock K-H, Lopez Abellan LJ, van de Putte AP (2014) Biogeographic patterns of fish. In: De Broyer C, Koubbi P, Griffiths HJ, Raymond B, d’Udekem d’Acoz C (eds) Biogeographic atlas of the southern ocean. Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, Cambridge, pp 328–362

Eakin RR (1977) Morphology and distribution of species in the genus Pogonophryne (Pisces, Harpagiferidae). In: Pawson DL, Kornicker LS (eds) Antarctic research series, biology of the Antarctic seas VIII, vol 28. American Geophysical Union, Washington, pp 1–20

Eakin RR (1981) Two new species of Pogonophryne (Pisces, Harpagiferidae) from the Ross Sea, Antarctica. In: Kornicker LS (ed) Antarctic research series, biology of the Antarctic seas IX, vol 31. American Geophysical Union, Washington, pp 149–154

Eakin RR (1987) Two new species of Pogonophryne (Pisces, Harpagiferidae) from the Weddell Sea, Antarctica. Arch FischWiss 38:57–74

Eakin RR (1990) Artedidraconidae. In: Gon O, Heemstra PC (eds) Fishes of the southern Ocean. J.L.B. Smith Institute of Ichthyology, Grahamstown, pp 332–356

Eakin RR, Balushkin AV (1998) A new species of toadlike plunderfish Pogonophryne orangiensis sp. nova (Artedidraconidae, Notothenioidei) from the Weddell Sea, Antartica. J Ichthyol 38:800–803

Eakin RR, Balushkin AV (2000) A new species of Pogonophryne (Pisces: Perciformes: Artedidraconidae) from East Antarctica. Proc Biol Soc Wash 113:264–268

Eakin RR, Eastman JT (1998) New species of Pogonophryne (Pisces, Artedidraconidae) from the Ross Sea, Antarctica. Copeia 4:1005–1009

Eakin RR, Eastman JT, Jones CD (2001) Mental barbel variation in Pogonophryne scotti Regan (Pisces: Perciformes: Artedidraconidae). Antarct Sci 13:363–370

Eakin RR, Eastman JT, Matallanas J (2008) New species of Pogonophryne (Pisces, Artedidraconidae) from the Bellingshausen Sea, Antarctica. Polar Biol 31:1175–1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-008-0455-7

Eakin RR, Eastman JT, Near TJ (2009) A new species and a molecular phylogenetic analysis of the Antarctic fish genus Pogonophryne (Notothenioidei: Artedidraconidae). Copeia 4:705–713

Eastman JT (2017) Bathymetric distributions of notothenioid fishes. Polar Biol 40:2077–2095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-017-2128-x

Eastman JT, Eakin RR (2021) Checklist of the species of notothenioid fishes. Antarct Sci 33:273–280. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102020000632

Eastman JT, McCune AR (2000) Fishes on the Antarctic continental shelf: evolution of a marine species flock? J Fish Biol 57(Suppl A):84–102. https://doi.org/10.1006/jfbi.2000.1604

Eastman JT, Amsler MO, Aronson RB, Thatje S, McClintock JB, Vos SC, Kaeli JW, Singh H, Mesa ML (2013) Photographic survey of benthos provides insights into the Antarctic fish fauna from the Marguerite Bay slope and the Amundsen Sea. Antarct Sci 25:31–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102012000697

Hanchet SM, Stewart AL, McMillan PJ, Clark MR, O’Driscoll RL, Stevenson ML (2013) Diversity, relative abundance, new locality records, and updated fish fauna of the Ross Sea region. Antarct Sci 25:619–636. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102012001265

La Mesa M, Piepenburg D, Pineda-Metz SEA, Riginella E, Eastman JT (2019) Spatial distribution and habitat preferences of demersal fish assemblages in the southeastern Weddell Sea (Southern Ocean). Polar Biol 42:1025–1040. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-019-02495-3

La Mesa M, Llompart F, Riginella E, Eastman JT (2021) Parental care and reproductive strategies in notothenioid fishes. Fish Fisher 22:356–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12523

Matschiner M, Colombo M, Damerau M, Ceballos S, Hanel R, Salzburger W (2015) The adaptive radiation of notothenioid fishes in the waters of Antarctica. In: Riesch R, Tobler M, Plath M (eds) Extremeophile fishes. Springer, Cham, pp 35–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13362-1_3

Near TJ, Dornburg A, Kuhn KL, Eastman JT, Pennington JN, Patarnello T, Zane L, Fernández DA, Jones CD (2012) Ancient climate change, antifreeze, and the evolutionary diversification of Antarctic fishes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:3434–3439. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1115169109

Parker E, Dornburg A, Struthers CD, Jones CD, Near TJ (2022) Phylogenomic species delimitation dramatically reduces species diversity in an Antarctic adaptive radiation. Syst Biol 71:58–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syab057/6319042

Acknowledgements

The photos of Pogonophryne immaculata were taken by Peter Marriott, the National Institute of Water and Atmosphere Ltd., New Zealand and provided by Andrew Stewart (National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa). We also thank him and an anonymous reviewer for their helpful comments for revising this manuscript.

Funding

JTE was supported by funding from Grants US NSF ANT 94-16870 and ANT 04-36190.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors participated in the analysis, writing, and final approval of this paper. RRE was responsible for recognizing, defining, and determining the species composition of the categories, species groups, and subgroups of Pogonophryne and also for supplying the original photographic prints for Figs. 2–4.

The P. barsukovi species group. Dorsal and lateral views of heads of Pogonophryne barsukovi (a, b), 217 mm and P. permitini (c, d), 126 mm. Both specimens are holotypes and females. From Andriashev (1967, Figs. 2, 3)

2,

The P. marmorata and P. mentella species groups. Dorsal and lateral views of the heads of Pogonophryne marmorata (a, b), 176 mm and P. mentella (c, d), 132 mm, holotype. Red arrows (a, b) indicate anterior area or gap within the orbit not filled by eye of P. marmorata. Both specimens are females. From Andriashev (1967, Figs. 2, 5)

3 and

The P. scotti species group. Dorsal and lateral views of the head (a, b) and trunk (c) of Pogonophryne scotti, 248 mm, male. From Andriashev (1967, Fig. 4)

4.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicting or competing interests.

Consent to participate

Both authors have given consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Both authors have given consent for publication.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was not needed for this particular study but, in a broader perspective, both authors followed all applicable national and institutional guidelines for the collection, care, and ethical use of research organisms and material in the conduct of the research, specifically those under protocol L01-14 as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Ohio University.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eastman, J.T., Eakin, R.R. Decomplicating and identifying species in the radiation of the Antarctic fish genus Pogonophryne (Artedidraconidae). Polar Biol 45, 825–832 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-022-03034-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-022-03034-3