Abstract

Objective

To describe the prevalence of and evaluate the factors associated with fatigue patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) in an Asian population.

Methods

We used baseline data from a registry of patients with PsA attending an outpatient clinic of a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Demographic data and disease characteristics were evaluated. Fatigue was assessed by question one of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI-F) and the vitality domain of the Medical Outcome Survey, Short-Form 36 (SF-36 VT). We evaluated clusters of variables, and individual variables in association with fatigue.

Results

We included 131 patients (50.4% men, 63.4% Chinese, median PsA duration 21.0 months) with completed data for fatigue. Forty-five patients (34%) experienced severe fatigue (defined by BASDAI-F > 5/10). We used principal component analysis and identified five clusters of variables that explained 62.9% of the variance of all factors. Of these, disease activity and impact, and disease chronicity were significantly associated with BASDAI-F and SF-36 VT. In multivariable analyses, back pain, peripheral joint pain and patient global assessment were associated with BASDAI-F, whereas peripheral joint pain and mental health were associated with SF-36 VT.

Conclusion

PsA-associated fatigue is prevalent in this Asian PsA cohort and is associated with disease activity, impact and chronicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic autoimmune disease with musculoskeletal manifestations of arthritis, dactylitis, enthesitis and spondylitis associated with skin psoriasis. Fatigue is ranked among the three most important domains according to patients with PsA [1, 2]. Its significance is formally recognised in the inner core of the OMERACT core set of domains and it is required to be reported in all clinical trials and longitudinal observational studies [3].

Fatigue has a detrimental impact on quality of life and physical fitness of patients with PsA [4]. It impairs activity participation, daily activities and contributes to work absenteeism [5], and should be treated as an independent outcome [6]. Fatigue is also a useful prodromal symptom of flares which patients can recognise to avoid flares of pain [7]. Despite its importance, fatigue as a subjective feeling of patients may not be readily recognized by healthcare providers [8, 9]. The pathogenesis of PsA-associated fatigue is not clearly understood, but generally thought to be multifactorial with immunologic, psychologic and physiologic components [10, 11]. Increased fatigue levels in PsA cohorts have been found to be associated with higher disease activity [12] and severe skin psoriasis [12, 13].

Most studies reporting on PsA-associated fatigue have been conducted in western populations and there are currently no data from Asian countries. It is well-known that ethnic, cultural and environmental factors influence the clinical manifestations of rheumatic illnesses including PsA [14, 15]. In a multinational study in rheumatoid arthritis, country of residence was shown to have a significant impact on fatigue [16]. These variations may arise from the interaction of one’s genetic background, socio-economic environment, symptom perception, as well as cultural influences on self-reporting of symptoms [14].

In this study, we aim to evaluate the prevalence of fatigue and the variables associated with fatigue in patients with PsA within a multi-ethnic Asian population.

Methods

Study design

We used baseline data from the PRESPOND (PREcision medicine in SPondyloarthritis for better Outcomes aNd Disease remission) registry with patients recruited from March 2013 to February 2018. We recruited consecutive patients attending a designated PsA clinic in Singapore General Hospital who were above the age of 18 years and fulfilled the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR) [17]. The SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol (CIRB Ref: 2012/498/E) and all patients provided written consent prior to the study.

Data collection

We collected demographic characteristics, clinical data and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) from each patient according to a standardized protocol. Patients were invited to complete self-administered questionnaires collecting data on their age, gender, ethnicity, highest education level and PROs. Body weight and height were measured in the clinic and the duration of PsA was derived from the date of diagnosis in clinical records.

The designated physician (YYL) assessed patients’ tender, swollen and damaged joint counts on a 66/68/68 diarthrodial joints diagram as previously described [14], dactylitis count (0–20), enthesitis count according to the 6-point Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI), and Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI). Data on physician’s global assessment (PhGA) were collected on a 0–10 numeric rating scale (NRS) (0 no disease activity to 10 worse disease activity). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was measured in each patient as part of routine care. Current conventional (c) disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) or biological (b) DMARDs were recorded (yes/no). The presence or absence of prevalent hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease and stroke was collected from case records.

For PROs, we collected patient global assessment (PGA) of disease activity in the past week on a 0–100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) (0 very good to 100 very bad), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) [18], Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI) (0 no disability to 3 severe disability), and 36-item Short-Form Health Survey version 2 (SF-36v2). Perceptions of axial and peripheral joint pain were assessed with the second and third questions of BASDAI, collected on a 0–10 NRS (0 none to 10 very severe). The criteria for minimal disease activity (MDA) were evaluated for each patient [19].

Measurements of fatigue

We used two fatigue measures—the first question of BASDAI (BASDAI-F) that asked the severity of fatigue in the past week, rated on a 0–10 NRS (0 none to 10 very severe) and the vitality domain of SF-36 (SF-36 VT). We defined severe fatigue as having a BASDAI-F score of > 5/10 [12, 20] and deemed a BASDAI-F score from 0 to 5 as nil-to-moderate fatigue. The SF-36 VT, one of the 8 SF-36 domains, is computed as a standardized score (0–100) based on responses to 4 questions on “feeling full of life”, “having a lot of energy”, “feeling worn out” and “feeling tired”. The SF-36 VT is a reverse concept of fatigue; higher SF-36 VT scores suggest lower levels of fatigue.

Statistical analysis

Results were shown as median (interquartile range, IQR), or mean (standard deviation, SD) when specified, for continuous variables; and number and percentages (%) of patients for categorical variables. We described and compared baseline characteristics of patients with severe and nil-to-moderate fatigue with chi-squared tests for categorical variables and Student’s t tests or Mann–Whitney U tests as appropriate for continuous variables.

We performed a principal component analysis (PCA), without rotation, to identify clusters of variables that were clinically relevant and distinct. These variables were selected based on theoretical link and results of previous studies [12, 13, 16, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. We only allowed variables with a predefined maximum collinearity of 0.6 into the model. Variables measuring similar concepts or had high collinearity were selected through a discussion among domain experts (YYL, WF, YHK).

Swollen joint count was chosen instead of tender joint count as it may better represent disease activity [31]; BASDAI-axial pain and BASDAI-peripheral joint pain were included separately as they measure different concepts; PhGA was excluded due to high collinearity with tender and swollen joint counts; SF-36 summary scores were not chosen as the eight domains of the SF-36 represent better-defined concepts. From the eight domains of SF-36, we included the mental health (MH) domain as it may represent the psychological status of patients that has been previously associated with fatigue [20, 32, 33]. Variables included in the final PCA were age, gender, ethnicity (Chinese vs. non-Chinese), education level (primary or below, secondary, tertiary), body mass index (BMI), duration of PsA, swollen joint count, clinically damaged joints, dactylitis, LEI, PASI, ESR, PGA, BASDAI-axial pain, BASDAI-peripheral joint pain, HAQ-DI and SF-36 MH. We evaluated the associations of the identified clusters of variables (components) with both fatigue measurement using linear regression models.

We conducted a univariable analysis for the association of variables with BASDAI-F and SF-36 VT using Spearman’s rho correlations. A Spearman’s rho > 0.7 was considered strong, > 0.5–0.7 was considered moderate, > 0.3–0.5 was considered weak, and < 0.3 was considered negligible [34].

We included in the multivariable analysis variables that had an association with fatigue with a significance level of p < 0.2 in the univariable analysis and other important variables as suggested by literature. Selected variables were analysed using stepwise linear regression models with both fatigue measurements.

We considered two-sided p values less than 0.05 as statistically significant. We performed all statistical analyses with IBM SPSS Statistic Package, version 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

Patient characteristics

We recruited 142 patients with PsA to the registry, of which 131 had completed data for both BASDAI-F and SF-36 VT at baseline and were included in the analysis. Characteristics of the total patient cohort with stratification to nil-to-moderate fatigue and severe fatigue are presented in Table 1. The mean (standard deviation, SD) age and median (interquartile range, IQR) duration of PsA were 50.1 (13.5) years and 21.0 (95.0) months, respectively. There were 66 (50.4%) men and 83 (63.4%) Chinese patients. Severe fatigue (BASDAI-F > 5/10) was experienced by 45 patients (34.4%).

Patients who reported severe fatigue had higher tender and swollen joint counts, enthesitis count and PhGA than those with nil-to-moderate fatigue. Patients with severe fatigue also reported significantly higher PGA, axial and peripheral joint pain, more disability by HAQ-DI and poorer health-related quality of life across all SF-36 domains. A significantly lower proportion of patients met the MDA criteria in the severe fatigue group as compared to the nil-to-moderate fatigue group (15.6% vs. 50.6%; p < 0.001). Among the 50 patients who were in MDA, 7 (14%) reported severe fatigue by BASDAI-F.

Principal component analysis

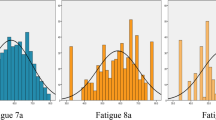

In the PCA of 17 selected variables, variables clustered to five components explaining a total of 62.9% of the variance (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1 [Online Resource]). The largest component, explaining 24.1% of the variance, reflected disease activity and impact. This component comprised HAQ-DI, BASDAI-peripheral joint pain, BASDAI-axial pain, PGA, SF-36 MH, swollen joint count, LEI, ESR, dactylitis and PASI. The second component, explaining 13.5% of the variance, reflected disease chronicity. This second component comprised age, education level, clinically damaged joints and ESR. In linear regression analyses of the five components, the first two components were statistically significantly associated with fatigue measured by both BASDAI-F and SF-36 VT. These 2 components representing (a) disease activity and impact and (b) disease chronicity explained 44.2% and 51.3% of the total variance of BASDAI-F and SF-36 VT, respectively.

Principal component analysis with 5 components and residuals (in dotted lines). Only factor loadings of magnitude greater than 0.40 are shown. PsA psoriatic arthritis; BMI body mass index; LEI Leeds Enthesitis Index; PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate; PGA patient global assessment; BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; HAQ-DI Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index; SF-36 Medical Outcome Short Form-36; MH, mental health

Univariable and multivariable analyses

In the univariable analysis (Table 2), PGA, BASDAI-axial and BASDAI-peripheral joint pain moderately and significantly correlated with BASDAI-F (rho ranges 0.52–0.59). Tender joint count, LEI, PhGA, HAQ-DI and SF-36 MH correlated weakly and significantly with BASDAI-F (rho ranges 0.31–0.40). The correlations between BASDAI-F and both ethnicity and swollen joint count were negligible but statistically significant.

In the univariable analysis for SF-36 VT, SF-36 MH was strongly and significantly correlated with SF-36 VT (rho = 0.70). Tender joint count, LEI, PhGA, PGA, BASDAI-axial pain, BASDAI-peripheral joint pain, and HAQ-DI weakly and significantly correlated with SF-36 VT (rho ranges 0.31–0.50). Age, BMI, dactylitis and ESR correlated significantly with SF-36 VT at negligible ranges.

In the multivariable analysis, age, ethnicity, BMI, duration of PsA, swollen joint count, LEI, PASI, ESR, PGA, BASDAI-axial pain, BASDAI-peripheral joint pain, HAQ-DI and SF-36 MH were included based on association with BASDAI-F with a p value < 0.2 in the univariable analysis. In addition, we included gender [12, 24] and education level [12] as they were associated with fatigue in previous studies. We also included the duration of PsA and clinically damaged joints to investigate chronicity and physical joint damage as potential variables which have been found to be associated with fatigue in a previous study [26].

Table 3 summarizes the results of the multivariable analysis for BASDAI-F and SF-36 VT, respectively. Variables that remained statistically significantly associated with BASDAI-F were BASDAI-axial pain, BASDAI-peripheral joint pain and PGA. Variables associated with SF-36 VT were BASDAI-peripheral joint pain and SF-36 MH.

Discussion

Fatigue is prevalent in our study cohort of Asian patients with PsA. More than a third (34.4%) of patients experienced severe fatigue with greater disease activity, disability and reduced health-related quality of life. In the PCA, fatigue was associated with clusters of variables representing concepts of disease activity and impact, and second, disease chronicity. In the multivariable analysis, variables of disease activity were the main drivers of fatigue after controlling for other variables. PGA, BASDAI-axial pain and peripheral joint pain were associated with BASDAI-F, while BASDAI-peripheral joint pain and SF-36 MH were associated with SF-36 VT.

The prevalence of severe fatigue in the current study was similar to that reported in the western literature [26, 30, 33, 35]. In a multinational study across 13 European countries in 246 PsA patients, 44.7% experienced high fatigue with the same definition of severe fatigue as this study (NRS fatigue score > 5/10) [12]. In a Canadian study of 499 PsA patients, 49.5% and 28.7% of patients with PsA experienced at least moderate and severe fatigue as defined by the modified fatigue severity scale ≥ 5 and ≥ 7, respectively [24]. In addition, we found that 14% of patients were in MDA and still reported having severe fatigue. Within our multi-ethnic cohort of PsA patients, non-Chinese patients were more likely to experience greater fatigue, but ethnicity was not statistically significantly associated with both measurements of fatigue in the multivariable analysis.

In the PCA, the clusters of variables explaining fatigue were disease activity and disease impact; disease chronicity came second. Disease chronicity may be contributed by structural damage from long-standing active PsA. These two components, namely disease activity and disease chronicity, were also found to have significant associations with fatigue in a PCA conducted within a Danish registry for PsA [26]. From both the PCA and regression models in the current study, the key driver of fatigue was disease activity. In the BASDAI-F model, both peripheral joint and axial pain were significantly associated with fatigue, while in the SF-36 VT model, only peripheral joint pain was associated with fatigue. Disease activity being the key driver of fatigue corroborates with findings from other PsA cohort studies conducted mainly among Caucasians [12, 20, 24, 27, 36]. The association of severity of skin psoriasis with fatigue was observed in some studies [12, 13]. In our study, PASI was clustered to the first variable cluster in the PCA and associated with fatigue, but statistical significance was lost in the regression models. This could be related to the relatively low severity of psoriasis in our PsA cohort (median PASI 1.5/72). Effective treatments for PsA like biologics generally reduce but do not completely eliminate fatigue, and the magnitudes of improvement of fatigue are generally lower than that for pain following biological treatments [37], which echoes our findings that 14% of patients who achieved MDA still experienced severe fatigue. This may indicate the existence of factors in addition to inflammation in the pathophysiology of fatigue, for which other dedicated treatment, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, may be required.

While the reason for the persistence of fatigue in PsA was not entirely clear [38], multiple factors, including disability [33], and psychological distress were thought to have important contributions [32, 33]. Variables clustered to central pain sensitization were also shown to be associated with fatigue in PsA [26]. Some studies postulate that along with chronic pain from joint symptoms and reduced physical fitness [5], elevated cytokine levels, such as IL-1β, in systemic inflammatory conditions exert central nervous system effects which contribute to fatigue [39, 40]. Psychological conditions, such as depression and anxiety, significantly exacerbate fatigue [32, 33], highlighting the central alteration of fatigue perceptions and the need to address these comorbidities of many chronic inflammatory diseases. We explored psychological status using the MH domain of SF-36 in the current study. The SF-36 MH clustered with the first component in the PCA with other variables of disease activity and impact. In the univariable analysis, statistically significant association of SF-36 MH with both BASDAI-F and SF-36 VT was shown; while in the multivariable analysis, SF-36 MH was only associated with SF-36 VT, but not with BASDAI-F. This may suggest the association of fatigue with mental health in our patients. However, this association may need to be interpreted with caution. Studies done in general populations in Asia or among Asian dependents have found that the SF-36 VT and MH had stronger correlations with each other than that reported by the western literature, casting doubts on whether SF-36 VT and MH are measuring distinct concepts [41, 42]. Furthermore, unlike BASDAI-F which enquires patients of fatigue attributable to their disease, SF-36 VT is a general measure of patients’ perceived energy. These reasons may explain the slight differences in variables associated with fatigue measured by these two different measures. Other patient-related factors, such as gender [12, 21,22,23,24], education level [12, 43] and comorbidities, such as sleeping disorders [44,45,46] and fibromyalgia [47], were found to be associated with fatigue in previous studies. In our study, ethnicity, age and BMI were associated with fatigue in the univariable analysis but became insignificant in the multivariable analysis.

Information of fatigue in PsA is scant in Asia, and to the best of our knowledge, variables associated with fatigue in PsA have not been explored before in Asia. Fatigue may be influenced by culture and geographical location [16]. Previous studies were all conducted mainly in Caucasian countries and the generalizability of their results to Asian populations is limited. A cohort study conducted within a multi-ethnic population has allowed us to study the effects of ethnicity, even though only Chinese and non-Chinese groups could be compared owing to the small sample size. The dataset comprised consecutive and all cases seen in a designated PsA clinic, minimizing selection bias. Furthermore, we were able to analyse a large set of variables, both clinical and PROs, for associations with fatigue. In this study, we used two fatigue measurements which have provided generally consistent perspectives on the variables associated with the concept of fatigue.

There are several limitations of our study. First, the cohort studied patients from a tertiary referral centre with results that may not be generalizable to milder PsA cases seen in general practices or dermatology settings. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow for causality inferences regarding the determinants of fatigue to be made and for longitudinal changes in fatigue to be assessed. Third, we used a single item BASDAI-F to measure fatigue which may be vulnerable to misinterpretation and measurement error. The SF-36 VT, therefore, served as a surrogate and similar results were demonstrated with an additional contribution by SF-36 MH. Notably, the SF-36 VT reflects a reverse concept of fatigue that may not necessarily have a specific attribution to PsA per se. We did not utilize other specific fatigue measures like the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Scale (FACIT-F) as they have not been translated and adapted for use in our population. Lastly, we did not include other psychological variables like central sensitization, fibromyalgia, anxiety and depression which may greatly impact fatigue, possibly accounting for the large unexplained variance in our PCA.

In conclusion, fatigue is a prevalent and important complaint among Asian patients with PsA even in those with minimal disease activity. Its association with disease activity and chronicity supports an inflammatory component which is amenable to treatment but does not fully explain its existence. PsA-associated fatigue has negative impact on physical disability and quality of life. Clinicians need to be mindful of this and identify potential patient-related factors to address this important domain.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Gossec L, de Wit M, Kiltz U, Braun J, Kalyoncu U, Scrivo R, Maccarone M, Carton L, Otsa K, Sooaar I, Heiberg T, Bertheussen H, Canete JD, Sanchez Lombarte A, Balanescu A, Dinte A, de Vlam K, Smolen JS, Stamm T, Niedermayer D, Bekes G, Veale D, Helliwell P, Parkinson A, Luger T, Kvien TK, Taskforce EP (2014) A patient-derived and patient-reported outcome measure for assessing psoriatic arthritis: elaboration and preliminary validation of the Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease (PsAID) questionnaire, a 13-country EULAR initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 73(6):1012–1019. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205207

Tillett W, Dures E, Hewlett S, Helliwell PS, FitzGerald O, Brooke M, James J, Lord J, Bowen C, de Wit M, Orbai AM, McHugh N (2017) A multicenter nominal group study to rank outcomes important to patients, and their representation in existing composite outcome measures for psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 44(10):1445–1452. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.161459

Orbai AM, de Wit M, Mease P, Shea JA, Gossec L, Leung YY, Tillett W, Elmamoun M, Callis Duffin K, Campbell W, Christensen R, Coates L, Dures E, Eder L, FitzGerald O, Gladman D, Goel N, Grieb SD, Hewlett S, Hoejgaard P, Kalyoncu U, Lindsay C, McHugh N, Shea B, Steinkoenig I, Strand V, Ogdie A (2017) International patient and physician consensus on a psoriatic arthritis core outcome set for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 76(4):673–680. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210242

Betteridge N, Boehncke W-H, Bundy C, Gossec L, Gratacós J, Augustin M (2016) Promoting patient-centred care in psoriatic arthritis: a multidisciplinary European perspective on improving the patient experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 30(4):576–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.13306

Merola JF, Shrom D, Eaton J, Dworkin C, Krebsbach C, Shah-Manek B, Birt J (2019) Patient perspective on the burden of skin and joint symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: results of a multi-national patient survey. Rheumatol Ther 6(1):33–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-018-0135-1

Minnock P, Kirwan J, Veale D, Fitzgerald O, Bresnihan B (2010) Fatigue is an independent outcome measure and is sensitive to change in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 28(3):401–404

Moverley AR, Vinall-Collier KA, Helliwell PS (2015) It’s not just the joints, it's the whole thing: qualitative analysis of patients' experience of flare in psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 54(8):1448–1453. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kev009

Wang CTM, Kwan YH, Fong W, Xiong SQ, Leung YY (2019) Factors associated with patient-physician discordance in a prospective cohort of patients with psoriatic arthritis: an Asian perspective. Int J Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185x.13568

Eder L, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Cook R, Gladman DD (2015) Factors explaining the discrepancy between physician and patient global assessment of joint and skin disease activity in psoriatic arthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 67(2):264–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22401

Rosen J, Landriscina A, Friedman AJ (2016) Psoriasis-associated fatigue: pathogenesis, metrics, and treatment. Cutis 97(2):125–132

Carneiro C, Chaves M, Verardino G, Drummond A, Ramos-e-Silva M, Carneiro S (2011) Fatigue in psoriasis with arthritis. Skinmed 9(1):34–37

Gudu T, Etcheto A, de Wit M, Heiberg T, Maccarone M, Balanescu A, Balint PV, Niedermayer DS, Canete JD, Helliwell P, Kalyoncu U, Kiltz U, Otsa K, Veale DJ, de Vlam K, Scrivo R, Stamm T, Kvien TK, Gossec L (2016) Fatigue in psoriatic arthritis - a cross-sectional study of 246 patients from 13 countries. Joint Bone Spine 83(4):439–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2015.07.017

Mease PJ, Karki C, Palmer JB, Etzel CJ, Kavanaugh A, Ritchlin CT, Malley W, Herrera V, Tran M, Greenberg JD (2017) Clinical and patient-reported outcomes in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) by body surface area affected by psoriasis: results from the Corrona PsA/spondyloarthritis registry. J Rheumatol 44(8):1151–1158. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.160963

Leung YY, Fong W, Lui NL, Thumboo J (2017) Effect of ethnicity on disease activity and physical function in psoriatic arthritis in a multiethnic Asian population. Clin Rheumatol 36(1):125–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-016-3460-1

Roussou E, Chopra S, Ngandu DL (2013) Phenotypic and clinical differences between Caucasian and South Asian patients with psoriatic arthritis living in North East London. Clin Rheumatol 32(5):591–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-012-2139-5

Hifinger M, Putrik P, Ramiro S, Keszei AP, Hmamouchi I, Dougados M, Gossec L, Boonen A (2015) In rheumatoid arthritis, country of residence has an important influence on fatigue: results from the multinational COMORA study. Rheumatology 55(4):735–744. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kev395

Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, Marchesoni A, Mease P, Mielants H (2006) Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 54(8):2665–2673. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.21972

Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A (1994) A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index. J Rheumatol 21(12):2286–2291

Coates LC, Fransen J, Helliwell PS (2010) Defining minimal disease activity in psoriatic arthritis: a proposed objective target for treatment. Ann Rheum Dis 69(01):48–53. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2008.102053

Walsh JA, McFadden ML, Morgan MD, Sawitzke AD, Duffin KC, Krueger GG, Clegg DO (2014) Work productivity loss and fatigue in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 41(8):1670–1674. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.140259

Nas K, Capkin E, Dagli AZ, Cevik R, Kilic E, Kilic G, Karkucak M, Durmus B, Ozgocmen S (2017) Gender specific differences in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 27(2):345–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/14397595.2016.1193105

Kalyoncu U, Bayindir O, Ferhat Oksuz M, Dogru A, Kimyon G, Tarhan EF, Erden A, Yavuz S, Can M, Cetin GY, Kilic L, Kucuksahin O, Omma A, Ozisler C, Solmaz D, Bozkirli ED, Akyol L, Pehlevan SM, Gunal EK, Arslan F, Yilmazer B, Atakan N, Aydin SZ (2017) The Psoriatic Arthritis Registry of Turkey: results of a multicentre registry on 1081 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 56(2):279–286. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kew375

Tobin AM, Sadlier M, Collins P, Rogers S, FitzGerald O, Kirby B (2017) Fatigue as a symptom in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: an observational study. Br J Dermatol 176(3):827–828. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15258

Husted JA, Tom BD, Schentag CT, Farewell VT, Gladman DD (2009) Occurrence and correlates of fatigue in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 68(10):1553–1558. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2008.098202

Klingberg E, Bilberg A, Bjorkman S, Hedberg M, Jacobsson L, Forsblad-d'Elia H, Carlsten H, Eliasson B, Larsson I (2019) Weight loss improves disease activity in patients with psoriatic arthritis and obesity: an interventional study. Arthritis Res Ther 21(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-019-1810-5

Skougaard M, Jorgensen TS, Rifbjerg-Madsen S, Coates LC, Egeberg A, Amris K, Dreyer L, Hojgaard P, Guldberg-Moller J, Merola JF, Frederiksen P, Gudbergsen H, Kristensen LE (2019) In psoriatic arthritis fatigue is driven by inflammation, disease duration, and chronic pain: An observational DANBIO registry study. J Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.181412

Mease PJ, Karki C, Palmer JB, Etzel CJ, Kavanaugh A, Ritchlin CT, Malley W, Herrera V, Tran M, Greenberg JD (2017) Clinical characteristics, disease activity, and patient-reported outcomes in psoriatic arthritis patients with dactylitis or enthesitis: results from the Corrona psoriatic arthritis/spondyloarthritis registry. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 69(11):1692–1699. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23249

Mease PJ, Palmer JB, Liu M, Kavanaugh A, Pandurengan R, Ritchlin CT, Karki C, Greenberg JD (2018) Influence of axial involvement on clinical characteristics of psoriatic arthritis: analysis from the corrona psoriatic arthritis/spondyloarthritis registry. J Rheumatol 45(10):1389–1396. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.171094

McDonough E, Ayearst R, Eder L, Chandran V, Rosen CF, Thavaneswaran A, Gladman DD (2014) Depression and anxiety in psoriatic disease: prevalence and associated factors. J Rheumatol 41(5):887–896. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.130797

Pilgaard T, Hagelund L, Stallknecht SE, Jensen HH, Esbensen BA (2019) Severity of fatigue in people with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and spondyloarthritis - results of a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 14(6):e0218831. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218831

Hensor EMA, McKeigue P, Ling SF, Colombo M, Barrett JH, Nam JL, Freeston J, Buch MH, Spiliopoulou A, Agakov F, Kelly S, Lewis MJ, Verstappen SMM, MacGregor AJ, Viatte S, Barton A, Pitzalis C, Emery P, Conaghan PG, Morgan AW (2019) Validity of a two-component imaging-derived disease activity score for improved assessment of synovitis in early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 58(8):1400–1409. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kez049

Carneiro C, Chaves M, Verardino G, Frade AP, Coscarelli PG, Bianchi WA, Ramos ESM, Carneiro S (2017) Evaluation of fatigue and its correlation with quality of life index, anxiety symptoms, depression and activity of disease in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 10:155–163. https://doi.org/10.2147/ccid.S124886

Husted JA, Tom BD, Farewell VT, Gladman DD (2010) Longitudinal analysis of fatigue in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 37(9):1878–1884. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.100179

Hinkle DE, Wiersma W, Jurs SG (2003) Applied statistics for the behavioral sciences. Houghton Mifflin College Division, Boston

Overman CL, Kool MB, Da Silva JA, Geenen R (2016) The prevalence of severe fatigue in rheumatic diseases: an international study. Clin Rheumatol 35(2):409–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-3035-6

Chandran V, Bhella S, Schentag C, Gladman DD (2007) Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue scale is valid in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 66(7):936–939. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2006.065763

Reygaerts T, Mitrovic S, Fautrel B, Gossec L (2018) Effect of biologics on fatigue in psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review with meta-analysis. Joint Bone Spine 85(4):405–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2018.01.011

Krajewska-Wlodarczyk M, Owczarczyk-Saczonek A, Placek W (2017) Fatigue - an underestimated symptom in psoriatic arthritis. Reumatologia 55(3):125–130. https://doi.org/10.5114/reum.2017.68911

Carmichael MD, Davis JM, Murphy EA, Brown AS, Carson JA, Mayer EP, Ghaffar A (2006) Role of brain IL-1β on fatigue after exercise-induced muscle damage. Am J Physiol Regul Int Compa Physiol 291(5):R1344–R1348. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00141.2006

Norden DM, Bicer S, Clark Y, Jing R, Henry CJ, Wold LE, Reiser PJ, Godbout JP, McCarthy DO (2015) Tumor growth increases neuroinflammation, fatigue and depressive-like behavior prior to alterations in muscle function. Brain Behav Immun 43:76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2014.07.013

Thumboo J, Fong KY, Machin D, Chan SP, Leong KH, Feng PH, Thio ST, Boey ML (2001) A community-based study of scaling assumptions and construct validity of the English (UK) and Chinese (HK) SF-36 in Singapore. Qual Life Res 10(2):175–188. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016701514299

Chang DF, Chun C-A, Takeuchi DT, Shen H (2000) SF-36 Health survey: tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability in a community sample of Chinese Americans. Med Care 38(5):542–548

Haroon M, Szentpetery A, Ashraf M, Gallagher P, FitzGerald O (2020) Bristol rheumatoid arthritis fatigue scale is valid in patients with psoriatic arthritis and is associated with overall severe disease and higher comorbidities. Clin Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-04945-4

Krajewska-Wlodarczyk M, Owczarczyk-Saczonek A, Placek W (2018) Sleep disorders in patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. Reumatologia 56(5):301–306. https://doi.org/10.5114/reum.2018.79501

Wong ITY, Chandran V, Li S, Gladman DD (2017) Sleep disturbance in psoriatic disease: prevalence and associated factors. J Rheumatol 44(9):1369–1374. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.161330

Sandikci SC, Colak S, Aydogan Baykara R, Oktem A, Cure E, Omma A, Kucuk A (2018) Evaluation of restless legs syndrome and sleep disorders in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Z Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00393-018-0562-y

Mease PJ (2017) Fibromyalgia, a missed comorbidity in spondyloarthritis: prevalence and impact on assessment and treatment. Curr Opin Rheumatol 29(4):304–310. https://doi.org/10.1097/bor.0000000000000388

Acknowledgements

No external editing agencies were employed in writing or submitting the manuscript.

Funding

YYL was supported by the National Medical Research Council, Singapore (NMRC/CSA-INV/0022/2017). The funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript writing, or decision to submit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YYL and WF conceptualized the study design. YYL acquired the data. JSQT and YYL performed the data analysis. All authors performed the data interpretation. JSQT and YYL wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

YYL has received speaking fee from Novartis, Janssen, Eli Lilly and AbbVie (all under US$10,000).

Ethics approval

The SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol (CIRB Ref: 2012/498/E).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This work has previously been submitted for the eular congress 2020 with the following abstract publication (doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-eular.2068): Tan Jsq, Fong W, Kwan Yh, Leung Yy (2020) ab0836 prevalence and determinants of fatigue in psoriatic arthritis in an asian population. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 79 (suppl 1):1723

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, J.S.Q., Fong, W., Kwan, Y.H. et al. Prevalence and variables associated with fatigue in psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatol Int 40, 1825–1834 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04678-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04678-2