Abstract

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is the most common chronic rheumatic disease of childhood resulting in disability in untreated cases. Disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs form the first-line treatment in JIA. However, the data about leflunomide (LFN) in treatment of JIA is limited. We reviewed the medical files of JIA patients who were followed-up regularly and had received LFN. A total of 38 patients were included to the study. Among them, 24 had oligoarticular JIA, eleven had polyarticular JIA, two had ERA and one had psoriatic arthritis. 36 were initially treated with methotrexate and two patients diagnosed with ERA were treated with sulfasalazine. Sulfasalazine treatment was switched to LFN due to inadequate response at the 3rd month of therapy. Methotrexate was ceased due to gastrointestinal intolerance in 36 patients. Of these 36 patients, 19 patients had either low disease activity (n = 13) or remission (n = 6). LFN was administered to 13 patients with low disease activity. During the follow-up of the six patients in remission, relapse ensued and LFN treatment was started. The remaining 17 patients had moderate (n = 10) or high (n = 7) disease activity requiring biologic agents. But due to inadequate response to biologic agents, LFN was added to the therapy. All of the patients were clinically inactive at the last visit. Only two adverse events resolving within 2 weeks were noted (Lymphopenia = 1, elevated liver enzymes = 1). LFN may be an alternative therapy in case of MTX intolerance or toxicity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by arthritis of unknown origin with onset before age of 16 years [1]. The primary aim of JIA treatment is to achieve clinically inactive disease and prevent deformities. In 2011, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published recommendations for treatment of JIA [2]. Subsequently, in 2014, the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) developed three consensus treatment plans (CTPs) for new-onset polyarticular JIA [3]. According to these recommendations, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) remained first-line therapy for children with JIA. Whereas the biological therapy has a significant place in treatment algorithms. Recently, studies concerning window of opportunity and early introduction of biological therapy are held. However, the cost and potential side effects should not be ignored when deciding to introduce or switch to biological therapy. Therefore, first line treatment of JIA is still DMARDs such as methotrexate (MTX), sulfasalazine and leflunomide (LFN). As MTX is the most commonly prescribed drug, studies mainly focus on effectiveness and safety of MTX. Most recently, ACR/Arthritis Foundation have published recommendations for treatment of JIA patients with non-systemic polyarthritis, sacroiliitis, and enthesitis [4]. They underlined that there is more evidence for MTX therapy than LFN therapy [4]. LFN may be an alternative option for the management of JIA, either as monotherapy for patients who respond but cannot tolerate MTX or as combination therapy for patients with an inadequate response to MTX. It is an immunomodulatory agent inhibiting de novo pyrimidine synthesis [5]. However, the data about efficacy and safety of LFN in patients with JIA is scarce. Herein, we aim to demonstrate our experiences with LFN treatment in patients with JIA.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical files of children (aged 0–18 years) who were diagnosed with JIA and had received LFN between January 2016 and January 2019. In our clinical practice, the first line treatment for JIA is either MTX or sulfasalazine. After 3 months of follow-up, some of the patients are not responding to these medications adequately. If the patients have low disease activity a switch to LFN is made. If the patients have high disease activity biological therapy is commenced. If there is inadequate response to biological drugs, LFN is added to therapy. When the patients do not tolerate MTX, a switch to LFN is made. Demographic data, clinical manifestations, laboratory data (white blood cell [WBC] count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], C-reactive protein [CRP], anti-nuclear antibody [ANA] positivity, rheumatoid factor [RF] positivity, human leucocytes antigen [HLA]-B27), and the concomitant treatment used were documented. All the samples were screened to ANA by indirect immunofluorescence on HEp-2 cells, using the commercially available kit ANA HEp-2 (Hemagen Diagnostics, Columbia, USA), as recommended by the manufacturer. A titer of 1:160 or higher on at least two occasions was considered to indicate ANA positivity. RF (IgM) levels were checked via Latex agglutination (Reference range for the test was 0–20 IU/ml). The presence of RF on two occasions at least 3 months apart was considered as RF positivity. Patients were classified as having JIA according to the ILAR criteria [1]. Disease activity was assessed with juvenile arthritis disease activity score 71 (JADAS71) in patients with oligoarticular or polyarticular JIA [6]. It is calculated using the formula: doctor’s visual analog scale (VAS) + patient’s VAS + count of joints with active arthritis + (ESR-20)/10 [6]. Patients with oligoarticular JIA were classified as having inactive disease if JADAS71 was < 1, low disease activity if JADAS71 was 1.1-2 and moderate if JADAS71 was 2.1–4.2 or high disease activity if JADAS71 was higher 4.2. Furthermore, patients with polyarticular JIA were classified as having inactive disease if JADAS71 was < 1, low disease activity if JADAS71 was between 1.1 and 3.8 and moderate if JADAS71 was between 3.9 and 10.5 or high disease activity if JADAS71 was higher than 10.5 [7]. Activity of disease was assessed by BASDAI scoring system in patients with ERA [8].

Methotrexate intolerance was defined as presence of any of the following findings: (1) gastrointestinal symptoms of various types, e.g., nausea, bloating, and distension, discomfort, pain, heaviness, acidity, epigastric distress, belching, loose motions, cramps, constipation; (2) behavioral symptoms including anticipatory symptoms, e.g., anxiety, depression, aversion to its name, sight, thought, aversion to food, unpleasant taste; (3) elevated transaminase (above 1.5 times the upper limit of normal) levels.

Patients with a body weight of < 20 kg were treated with 10 mg LFN on alternate days; patients with a body weight of > 20 kg and < 40 kg received 10 mg LFN every day, and patients weighing > 40 kg received 20 mg LFN every day.

Patients were classified as familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) according to the pediatric FMF criteria [9]. Mediterranean Fever (MEFV) gene variant analysis was performed with Sanger sequencing in the department of genetics. Exon 2, 3, 5 and 10 were tested in the MEFV gene.

The study was reviewed and approved by the ethical review committee of Kanuni Sultan Süleyman Training and Research Hospital. Patient files were evaluated retrospectively and all patients were anonymous. When the patients were admitted to the hospital, the parents gave a general consent approving anonymous data use for academic purpose.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software version 15. The variables were investigated using visual (histogram, probability plots) and analytic methods (Kolmogorov–Smirnov/Shapiro–Wilk’s test) to determine whether or not they are normally distributed. Descriptive analyses are presented using proportions, medians, minimum (min) and maximum (max) values as appropriate. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare the non-normally distributed variables between dependent groups. A P value < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant result.

Results

Totally 38 patients were included to the study. Among them, 17 were male and 21 were female. Of 38 patients, 24 (63.1%) had persistent oligoarticular JIA, eleven (28.9%) had polyarticular JIA, two (5.2%) had ERA and one (2.6%) had psoriatic arthritis. The median (min–max) age of symptom onset, diagnosis and current age were 10.5 (1–16), 11 (1–16), and 15 (5–16), respectively. The median (min–max) WBC count was 11700 (7400–18000) × 103/mm3, ESR was 28 (3–60) mm/h, CRP was 11.4 mg/dL (0.4–56), and JADAS71 was 13 (4–35) at the time of diagnosis. ANA was positive in 12 patients with oligoarticular JIA, two patients with polyarticular JIA were RF positive and one had anti-CCP antibody. Two patients with ERA were HLA-B27 positive (Table 1). Among 38 patients, two patients had uveitis and two patients had familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) concomitant to JIA. One of them carried G138G/A165A mutation and the other was homozygous for M694V.

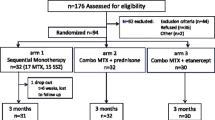

Among 38 patients, 36 were initially treated with methotrexate (MTX) (15 mg/m2/week, subcutaneous) and non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Fig. 1). The remaining two patients diagnosed with ERA were treated with sulfasalazine. Furthermore, 20 patients received short-term bridging steroid therapy (1–2 mg/kg/day; tapered and ceased within 1 month). Sulfasalazine treatment was switched to LFN due to inadequate response (morning stiffness and arthritis) at the 3rd month in two patients with ERA. These two patients did not achieved remission at the 3th month So, finally etanercept was administered concomitant to LFN.

Methotrexate was ceased due to gastrointestinal intolerance in 36 patients. Among them, 33 patients suffered from nausea-vomiting and three patients had elevated liver enzymes. The median (min–max) duration of MTX treatment was 5 (1–75) months. Of 36 patients, 19 patients had either low disease activity (n = 13) or remission (n = 6). LFN was administered to 13 patients with low disease activity. Six patients had remission and were followed without medication (Fig. 1), but after 2 (1–5) months of MTX cessation, they had relapse and so LFN treatment was started. The median (min–max) WBC count was 9600 (7400–16,000) × 103/mm3, ESR was 14 (10–28) mm/h, CRP was 5.8 (range 2–9.2), and JADAS71 was 1.1 (1.1–2) at the time of LFN initiation. At the 3th month of LFN initiation, 15 patients achieved remission and four had inadequate response and biologic agents (etanercept = 1, adalimumab = 3) were administered concomitant to LFN. The median follow-up of these patients were 12 (6–24) months. All of them were inactive at the last visit.

The remaining 17 patients had moderate (n = 10) or high (n = 7) disease activity (Fig. 1). Biologic agents were started to these patients (etanercept = 11, adalimumab = 5, tocilizumab = 1). Subsequently, patients who received biologic agents had disease activation after 11.5 (5–36) months and LFN was prescribed concomitant to biologic agents. The median (min–max) WBC count was 10,700 (6400–14,200) × 103/mm3, ESR was 24 (10–30) mm/h, CRP was 9.8 (range 1–18), and JADAS71 was 3.2 (1–5.1) at the time of LFN initiation. The median follow-up after LFN initiation was 11 (6–36) months. All of the patients were clinically inactive at the last visit.

We checked the patients every 2 weeks in the first month of treatment, then every month during the follow-up period. Two patients had adverse events. One had lymphopenia (lymphocyte count = 900/mm3) resolving spontaneously within 2 weeks of cessation of LFN and the other patient had elevated liver enzymes (aspartate transaminase = 136 U/L and alanine transaminase = 126 U/L) and was under adalimumab and colchicine treatment besides LFN. LFN was discontinued for 2 weeks and after normalization of liver enzymes LFN was re-started without new side effects.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that LFN remained a valid alternative therapy in case of MTX intolerance or toxicity. Furthermore, it is safe when used concomitantly with biologic agents. This is one of the widest monocentric case series of JIA patients treated with LFN.

There were few studies regarding to the efficacy of LFN in JIA. Silverman et al., conducted an open label study to assess the efficacy and safety of LFN in polyarticular JIA patients. This study consists of 26-week duration and further 2-year extension phase. They demonstrated response rate as 52% in 26 weeks and 53% in patients who entered into the extension phase [5]. Subsequently, a multicenter multinational randomized controlled study had shown that methotrexate and LFN had similar rates of clinical improvement, but the rate of improvement was slightly higher in polyarticular JIA patients treated with MTX [10]. A study from China evaluated the combined MTX and LFN treatment and demonstrated that combination of LFN and MTX in patients with active polyarticular JIA was better than MTX therapy alone [11]. They have also showed that the combination therapy with LFN and MTX was safe and well tolerated [11]. Chickermane et al. [12] have also showed the efficacy of LFN contaminant to MTX in case of polyarticular JIA patients failing standard dose of MTX. In presented study, we showed that LFN may be an alternative treatment option in patients who were intolerant to MTX. In case of patients with low disease activity, LFN may reduce the requirement for biologic agents. Alcântara et al. [13] also reported 43 patients with JIA who were successfully treated with LFN with a long term follow-up.

Effectiveness of LFN in uveitis is controversial. Molina et al. [14] had reported that patients with JIA associated uveitis had a 61.5% of response rate under LFN treatment. However, Bichler et al. [15] had shown that patients with JIA had significantly more uveitis flares on LFN compared to MTX. In our cohort, two patients had uveitis and two of them were inactive with adalimumab and LFN.

According to adult studies, LFN may be combined with biologic agents in unresponsive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients. However, the data about concomitant use of biologic agents and LFN is insufficient in childhood. We demonstrated that using LFN with biologic agents was safe and well tolerated in our cohort of 21 patients.

The most common adverse effects of leflunomide are gastrointestinal symptoms including abdominal pain, dyspepsia, anorexia, diarrhea and elevated hepatic transaminases Furthermore, the most common reasons for discontinuation were nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abnormal liver function test results [16]. In presented study, only two adverse events completely resolving within 2 weeks of cessation of LFN were reported.

Our study is limited by the confounding factors associated with small sample size and its retrospective design.

In conclusion, our findings support that LFN may be an effective treatment alternative in patients with MTX intolerance and in presence of low disease activity may diminish the requirement for biologic agents. Even though, we did not observe any adverse effect among our patients, prospective trials with larger series are needed to show the safety of adding LFN to biologic agents in case of inadequate response to biological drugs.

References

Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, Goldenberg J, International League of Associations for R et al (2004) International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheum 31:390–392

Beukelman T, Patkar NM, Saag KG, Tolleson-Rinehart S, Cron RQ, DeWitt EM, Ilowite NT et al (2011) 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: initiation and safety monitoring of therapeutic agents for the treatment of arthritis and systemic features. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 63:465–482

Ringold S, Weiss PF, Colbert RA, DeWitt EM, Lee T, Onel K, Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Research Committee of the Childhood A, Rheumatology Research A et al (2014) Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance consensus treatment plans for new-onset polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 66:1063–1072

Ringold S, Angeles-Han ST, Beukelman T, Lovell D, Cuello CA, Becker ML et al (2019) 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: therapeutic Approaches for Non-Systemic Polyarthritis, Sacroiliitis, and Enthesitis. Arthritis Rheumatol 71:846–863

Silverman E, Spiegel L, Hawkins D, Petty R, Goldsmith D, Schanberg L et al (2005) Long-term open-label preliminary study of the safety and efficacy of leflunomide in patients with polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 52:554–562

McErlane F, Beresford MW, Baildam EM, Chieng SE, Davidson JE, Foster HE et al (2013) Validity of a three-variable juvenile arthritis disease activity score in children with new-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 72:1983–1988

Demirkaya E, Consolaro A, Sonmez HE, Giancane G, Simsek D, Ravelli A (2016) Current research in outcome measures for pediatric rheumatic and autoinflammatory diseases. Curr Rheumatol Rep 18:8

Akkoc Y, Karatepe AG, Akar S, Kirazli Y, Akkoc N (2005) A Turkish version of the bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index: reliability and validity. Rheumatol Int 25:280–284

Yalcinkaya F, Ozen S, Ozcakar ZB, Aktay N, Cakar N, Duzova A et al (2009) A new set of criteria for the diagnosis of familial Mediterranean fever in childhood. Rheumatol (Oxf) 48:395–398

Silverman E, Mouy R, Spiegel L, Jung LK, Saurenmann RK, Lahdenne P et al (2005) Leflunomide or methotrexate for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 352:1655–1666

Gao JS, Wu H, Tian J (2003) Treatment of patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis with combination of leflunomide and methotrexate. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 41:435–438

Chickermane PR, Khubchandani RP (2015) Evaluation of the benefits of sequential addition of leflunomide in patients with polyarticular course juvenile idiopathic arthritis failing standard dose methotrexate. Clin Exp Rheumatol 33:287–292

Alcantara AC, Leite CA, Leite AC, Sidrim JJ, Silva FS Jr, Rocha FA (2014) A longterm prospective real-life experience with leflunomide in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 41:338–344

Molina C, Modesto C, Martin-Begue N, Arnal C (2013) Leflunomide, a valid and safe drug for the treatment of chronic anterior uveitis associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 32:1673–1675

Bichler J, Benseler SM, Krumrey-Langkammerer M, Haas JP, Hugle B (2015) Leflunomide is associated with a higher flare rate compared to methotrexate in the treatment of chronic uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 44:280–283

Smolen JS, Kalden JR, Scott DL, Rozman B, Kvien TK, Larsen A, Loew-Friedrich I, Oed C, Rosenburg R (1999) Efficacy and safety of leflunomide compared with placebo and sulphasalazine in active rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, randomised, multicentre trial. European Leflunomide Study Group. Lancet 353:259–266

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NAA wrote and revised the paper and together with SGK interpreted the data and formulated conclusions. HES and AT also wrote the statistical analysis plan, cleaned and analyzed the data, and revised each draft. FÇ and MÇ was involved with study design and recruitment. All authors approved the final version of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the ethical review committee of Kanuni Sultan Süleyman Training and Research Hospital.

Informed consent

All these patient files were evaluated retrospectively and all patients were anonymous. When the patients admitted to the hospital, the parents gave a general consent approving anonymous data use for academic purpose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ayaz, N.A., Karadağ, Ş.G., Çakmak, F. et al. Leflunomide treatment in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatol Int 39, 1615–1619 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04385-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04385-7