Abstract

Purpose

AZD7762 is a Chk1 kinase inhibitor which increases sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents, including gemcitabine. We evaluated the safety of AZD7762 monotherapy and with gemcitabine in advanced solid tumor patients.

Experimental design

In this Phase I study, patients received intravenous AZD7762 on days 1 and 8 of a 14-day run-in cycle (cycle 0; AZD7762 monotherapy), followed by AZD7762 plus gemcitabine 750–1,000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8, every 21 days, in ascending AZD7762 doses (cycle 1; combination therapy).

Results

Forty-two patients received AZD7762 6 mg (n = 9), 9 mg (n = 3), 14 mg (n = 6), 21 mg (n = 3), 30 mg (n = 7), 32 mg (n = 6), and 40 mg (n = 8), in combination with gemcitabine. Common adverse events (AEs) were fatigue [41 % (17/42) patients], neutropenia/leukopenia [36 % (15/42) patients], anemia/Hb decrease [29 % (12/42) patients] and nausea, pyrexia and alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase increase [26 % (11/42) patients each]. Grade ≥3 AEs occurred in 19 and 52 % of patients in cycles 0 and 1, respectively. Cardiac dose-limiting toxicities occurred in two patients (both AZD7762 monotherapy): grade 3 troponin I increase (32 mg) and grade 3 myocardial ischemia with chest pain, electrocardiogram changes, decreased left ventricular ejection fraction, and increased troponin I (40 mg). AZD7762 exposure increased linearly. Gemcitabine did not affect AZD7762 pharmacokinetics. Two non-small-cell lung cancer patients achieved partial tumor responses (AZD7762 6 mg/gemcitabine 750 mg/m2 and AZD7762 9 mg cohort).

Conclusions

The maximum-tolerated dose of AZD7762 in combination with gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 was 30 mg. Although development of AZD7762 is not going forward owing to unpredictable cardiac toxicity, Chk1 remains an important therapeutic target.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many classical cytotoxic drugs and radiation therapies cause damage to DNA. Studies conducted in the 1980s demonstrated that eukaryotic cells respond to this damage by halting cell cycle progression through activation of cell cycle checkpoints [1, 2]. During the ensuing pause in growth, cells may repair DNA lesions and continue growth. If the DNA damage cannot be repaired, or attempted chromosomal segregation occurs prior to completion of repair, cell death occurs [3]. The existence of DNA damage can be understood as a signaling event, activating a cascade of cellular responses ultimately directed at restoring normal DNA structure through checkpoint-mediated pausing of cell cycle progression, or eliminating an irrevocably damaged cell by induction of apoptosis. The ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and the ataxia telangiectasia related (ATR) kinases are activated in response to double-strand breaks and, in turn, activate the checkpoint kinases Chk1 and Chk2. Chk1 then inhibits cdc25A phosphatase, resulting in cell cycle arrest in G2, and activates rad51 and related pathways to accomplish DNA repair [4]. Chk2 and ATM activate the tumor suppressor TP53, which activates transcription of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p21, causing cell cycle arrest in the G1 and G2 phases of the cell cycle [4]. TP53 can also induce the transcription of the B cell lymphoma-associated X (BAX) and p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) pro-apoptotic proteins which contribute to the occurrence of cytotoxicity in the event that DNA damage is not reversible [5].

Certain drugs, notably caffeine and other methylxanthines, were recognized in the 1990s as being able to abrogate cell cycle arrest after exposure to radiation and chemotherapeutic agents [6]. By eliminating the time for DNA repair, these agents were characterized as inducing ‘mitotic catastrophe’ and therefore had the potential to enhance the cytotoxic effects of both radiation and DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic agents. However, the >10−4 M concentrations at which methylxanthines acted to abrogate checkpoint function were greatly in excess of pharmacologically tolerable levels in humans [7, 8]. UCN-01 (7-hydroxyl-staurosporine) was recognized as diminishing the G2 fraction of certain cell lines [9]; it was subsequently shown to be a potent inhibitor of Chk1 which sensitized many cell types, including p53 mutant cells, to the effects of chemotherapeutic agents and radiation [10–12]. Unfortunately, the clinical development of UCN-01 was complicated by unfavorable pharmacology [13, 14], with a functionally narrow therapeutic window compared with other kinases [notably phosphatidylinositide-dependent kinase (PDK)-1] [15], and an association with insulin resistance and prominent dose-limiting hyperglycemia [14].

AZD7762 (AstraZeneca) is a potent and selective ATP-competitive Chk1 kinase inhibitor that has shown chemosensitizing activity with DNA-damaging agents, including gemcitabine and SN-38 (the active metabolite of irinotecan), in in vitro and in vivo model systems [16, 17]. Here, we report the findings of the first human study of AZD7762 given in combination with gemcitabine to patients with advanced solid tumors.

Patients and methods

Objectives

The primary objective was to assess the safety and tolerability of AZD7762 monotherapy (cycle 0) and in combination with gemcitabine (cycle 1 and subsequent cycles) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Secondary objectives were to assess the single-dose pharmacokinetics (PK) of AZD7762 alone and in combination with gemcitabine as well as to assess the preliminary efficacy of this combination regimen. An exploratory objective was to explore the effect of AZD7762 in combination with gemcitabine on cell cycle checkpoint biomarkers pChk1ser345 and pH2AX (DNA repair and apoptosis biomarkers, respectively) in skin and tumor biopsies.

Patients

Patients aged ≥18 years were eligible if they had a histologically or cytologically confirmed solid malignancy that was metastatic or unresectable and refractory to standard therapies, or for which no standard therapy exists, and with an ECOG performance status of 0–1. Patients were excluded if they had inadequate bone marrow reserve (absolute neutrophil count ≤1.5 × 109/l, platelet count ≤100 × 109/l, or hemoglobin ≤9 g/dl); inadequate liver function [serum bilirubin ≥1.5 times the upper limit of reference range (ULRR), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ≥2.5 times ULRR (≥5 times the ULRR where liver metastasis was present)]; glomerular filtration rate measured or derived by Cockroft–Gault equation ≤50 ml/min and serum creatinine ≥1.3 times the upper limit of normal; radiotherapy or major surgery within 4 weeks of study entry; last dose of systemic chemotherapy within 14 days of first dose of AZD7762; unresolved toxicity from previous chemotherapy of National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria Adverse Event (CTCAE) version 3.0 grade >1; brain metastasis or spinal cord compression (unless surgically removed and/or irradiated ≥4 weeks prior to study entry and stable without steroid treatment for ≥1 week); pregnancy or breast feeding; or any severe concomitant condition that in the opinion of the investigator made it undesirable for the patient to participate in the study.

Specific cardiac-related exclusion criteria were troponin I increase of CTCAE grade ≥1; stage II, III, or IV cardiac status (New York Heart Association classification); coronary artery disease or arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease within the previous 6 months; Mobitz type 2 second-degree heart block; resting left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <55 % measured by multiple gated acquisition (MUGA) or echocardiogram (ECHO); PR interval >217 ms; prior anthracycline treatment; and concurrent use of any potent negative inotropic drug.

Study design

This was a Phase I, open-label, multicenter dose-escalation study, using a standard 3 + 3 design, and was carried out at three oncology centers in the USA (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00413686). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice, and AstraZeneca policy on Bioethics [18] and was approved by the appropriate independent review boards. All patients provided written informed consent.

In the first cycle (cycle 0), patients received a single dose of AZD7762 administered as a 60-min iv infusion on days 1 and 8 of a 14-day run-in cycle. In subsequent cycles, patients received AZD7762 at the same dose as cycle 0 in combination with 750 or 1,000 mg/m2 gemcitabine administered as a 30-min iv infusion. The somewhat lower dose of gemcitabine that is usual for clinical practice in the first patient cohort was in the interest of safety, in the event that an unexpectedly potent interaction between AZD7762 and gemcitabine might occur. The first seven patients received combination treatment on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle. Following a protocol amendment to increase tolerability and acceptability in this heavily pretreated population, subsequent patients received combination treatment on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle. On cycle 1, day 1, AZD7762 was administered 4 h after gemcitabine to allow for PK and pharmacodynamic (PD) evaluation. However, for subsequent cycles, AZD7762 infusion began immediately after completion of gemcitabine infusion. Patients could continue therapy providing they were benefiting and had not experienced a cardiac dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) or any other intolerable toxicity.

Dose escalation and dose-limiting toxicities

The starting dose of AZD7762 was 6 mg. If no DLTs (see below) occurred in a cohort of ≥3 patients, the next dose cohort was started. AZD7762 dose cohorts were 6, 9, 14, 21, 32, 30, and 40 mg. For the first dose escalation, only the dose of gemcitabine was increased (from 750 to 1,000 mg/m2); AZD7762 dose was increased for all additional dose escalations (gemcitabine was dosed at 1,000 mg/m2). If one patient experienced a DLT, the cohort would be expanded to six patients and dose escalation could continue if no further patients experienced a DLT. If two or more patients experienced a DLT in the same cohort, the dose was considered non-tolerable, dose escalation was stopped, and the previous lower dose was considered the maximum-tolerated dose (MTD).

DLT was evaluated during cycles 0 and 1. DLTs were defined as CTCAE grade ≥3 troponin I increase in the absence of a well-defined concurrent event such as sepsis or pulmonary embolism (well-described causes for non-cardiac increase of troponin); grade ≥2 decrease in LVEF, with a value representing a minimum 10-point decrease from baseline to a value of <50 % or an absolute decrease of ≥16 % in a LVEF value that was above 50 % for ≥24 h post-dose; or any other grade ≥3 toxicity (in cycle 0; for cycle 1, this was modified to CTCAE grade 4 neutropenia for more than 4 days or grade ≥3 neutropenia complicated with ≥38.5 °C fever; grade ≥3 ALT and/or AST increase in patients with liver metastases lasting >7 days; grade ≥4 emesis for more than 24 h despite aggressive management; and any grade >3 non-hematological toxicity). During cycle 0, an additional DLT criteria of any CTCAE grade ≥2 cardiac toxicity lasting >24 h (except troponin I increase) was applied.

Assessments

Adverse events (AEs) were recorded throughout the treatment period and for 30 days after discontinuation of study treatment, using CTCAE version 3.0. Cardiac monitoring [MUGA or ECHO and ECG (electrocardiogram)] was performed at baseline, on days 1 and 8 of cycle 0 and 1, and on day 1 of each subsequent cycle and if clinically indicated. If LVEF declined by ≥10 points from baseline to a value <50 %, or there was an absolute decrease of ≥16 % in a LVEF value that was above 50 % for ≥24 h, assessment was repeated the following day. Central cardiac troponin I measurements were made pre-infusion, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h after the first infusion; pre-infusion, 4 and 24 h after the second and third infusions; and pre-infusion and 4 h after subsequent AZD7762 infusions. Following start of treatment, troponin I levels were measured using the Bayer Tnl-Ultra high sensitivity method, and severity graded according to the following stratification: 0.04 < grade 1 < 0.07 ng/ml; 0.07 ≤ grade 2 < 0.1 ng/ml; 0.1 ≤ grade 3 < 1.0 ng/ml; grade 4 ≥ 1.0 ng/ml. An ECG was required in the event of an increased local or central troponin I level. Hematology and clinical chemistry assessments were performed at baseline, weekly during cycles 0 and 1, on day 1 of cycle 2, weekly thereafter for hematology and 3-weekly thereafter for clinical chemistry.

Blood samples were collected on days 1 and 8 of cycles 0 (at pre-dose, 0.92, 1.03, 1.25, 1.5, 2, 3, 5, 7, 25, and 26 h after start of infusion) and 1 (at pre-dose, 4.5 and 25 h after start of infusion), and urine samples were collected on days 1 (pre-dose, 0–6, 6–12, 12–24 h intervals) and 2 (0–12 and 12–24 h intervals) of cycle 1 for analysis of PK parameters as described previously [19]. Plasma concentrations of AZD7762 were determined by York Bioanalytical Solutions Ltd. UK, using high-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass-spectrometric detection (HPLC MS/MS).

Tumor assessments were performed according to Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST, version 1.0 [20]) at screening, between days 10 and 15 (if the previous assessment was scheduled to be >28 days from the first combination dose), day 1 of cycle 3, and subsequently after every three cycles of treatment.

Paired skin biopsies for PD assessment of hair follicles were taken on day 1 of cycle 1, 3–4 h after the start of gemcitabine infusion and then 3–4 h after the start of AZD7762 infusion. Biopsy tissue was stained for pChk1ser345 and pH2AX using immunohistochemistry and antibodies as described previously [17, 21], as those markers were clearly indicative of drug effect in preclinical models. Stained tissue sections were given an H-score of 0–12 based on the overall intensity of cell staining (0, no staining; 1, weak staining; 2, moderate staining; 3, strong staining) multiplied by the percentage of cells stained (0, 0 %; 1, >0 to ≤25 %; 2, >25 to ≤50 %; 3, 50 to ≤75 %; 4, >75 %).

Statistics

No formal statistical analyses comparing dose groups were performed. Safety, PK, efficacy, and PD data were summarized with descriptive statistics only. Following log transformation of AZD7762 clearance rates, the effect of dosing regimen was analyzed using a mixed effects ANCOVA model including regimen (monotherapy and in combination with gemcitabine) and log dose. The least squares mean difference in AZD7762 clearance between the regimens was presented with the corresponding 2-sided 90 % confidence interval on a linear scale.

Results

Patient characteristics and disposition

Forty-two patients (22 male and 20 female) received at least one dose of AZD7762 and were evaluable for safety and PK analysis (Table 1); 38 patients were evaluable for efficacy and DLT assessments. Seven patients were excluded from analysis because they did not complete the required treatment duration in cycle 0 and 1, and did not experience any DLTs; further, four of these patients did not have measurable disease at baseline and therefore could not be included in the tumor assessments. The first patient was enrolled on the study on December 14, 2006, and the last patient completed study treatment on May 6, 2010. The median duration of AZD7762 treatment across all doses was 43 days (range 1–318), and the median number of cycles completed was 3 (0–13). The median duration of gemcitabine treatment was 29 days (range 1–304), and the median number of cycles completed was 2 (0–12). The most common reasons for discontinuation were progression of disease (29 patients), AEs (six patients), and voluntary discontinuation (two patients).

Safety and tolerability

Overall, the most commonly reported AEs were fatigue [41 % (17/42) patients], neutropenia/leukopenia [36 % (15/42) patients], anemia/Hb decrease [29 % (12/42) patients], and nausea, pyrexia, and ALT/AST increase [26 % (11/42) patients] each; Table 2). During cycle 0 (AZD7762 alone), the most frequent AEs were fatigue [14 % (6/42) patients], vomiting [14 % (6/42) patients], and nausea [12 % (5/42) patients]. AEs of CTCAE grade ≥3 were reported by 19 % (8/42) of patients in cycle 0 (AZD7762 alone) and 52 % (22/42) of patients in cycle 1 (AZD7762 in combination with gemcitabine; Table 3). Three patients experienced serious AEs (SAEs) considered by the investigator to be possibly related to AZD7762: grade 3 chest pain in a patient in the AZD7762 30 mg group; grade 4 neutropenia, grade 3 leukopenia and grade 3 device-related infection, in a patient in the AZD7762 40 mg group (events in both patients were judged to also be causally related to gemcitabine, except for device-related infection); and grade 3 myocardial ischemia in a patient in the AZD7762 40 mg group, which was also recorded as a DLT.

The MTD of AZD7762 in combination with gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 was determined to be 30 mg. In cycle 0, cardiac DLTs occurred in two patients: one at an AZD7762 dose of 32 mg (asymptomatic grade 3 troponin I increase) and one at an AZD7762 dose of 40 mg (grade 3 myocardial ischemia associated with chest pain, ECG changes, decreased LVEF, and increased troponin I). In both patients, these events were reversible following permanent discontinuation of AZD7762. In cycle 1, two additional patients reported non-cardiac DLTs; one patient at an AZD7762 dose of 32 mg (grade 3 nausea/vomiting for 2 days; the patient was hospitalized and the event was reported as a SAE) and one patient at an AZD7762 dose of 40 mg (grade 4 neutropenia complicated by ≥38.5 °C fever for 2 days; the patient was hospitalized and the event was reported as a SAE), in combination with gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2.

There were seven deaths during the study, six due to disease progression and one due to an AE of endocarditis, which was considered by the investigator to be unrelated to study treatment.

Pharmacokinetics

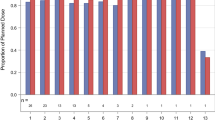

The PK parameters of AZD7762 as a single agent and in combination with gemcitabine are summarized in Table 4. AZD7762 exposure (C max, C 24 h, and AUC) increased in a dose-proportional manner over the dose range studied (Table 4; Fig. 1). Following AZD7762 monotherapy, the mean half-life ranged from 8–15.5 h and mean clearance ranged from 35–73 l/h. The treatment ratio of AZD7762 combination to AZD7762 alone was 0.93, 90 % CI (0.80, 1.08); hence, gemcitabine did not appear to affect the PK of AZD7762. Analysis of urine samples indicated that across all dose levels 11–20 % of unchanged drug was excreted in the urine during the first 48 h post-dosing. Plasma concentrations at doses of AZD7762 >21 mg were consistent with those found to be biologically effective in preclinical studies (data on file).

Pharmacodynamics

The PD effect of AZD7762 alone and in combination with gemcitabine was evaluated in hair follicles from skin biopsies. The degree of staining for both Chk1 and pH2AX was minimal (<25 %) and as a result, the H-scores for both biomarkers ranged from 0–3 out of 12. Consequently, staining results were compared according to percentage overall staining rather than H-score. There were small increases in staining of pChk1ser345 and pH2AX in samples from patients in the 32 mg cohort (Fig. 2), but no increased staining in other dose cohorts. The lack of effect at 40 mg is likely to reflect the limited number of samples at this higher than MTD, as well as variability, since it is close to the bottom of the concentration-effect curve for augmenting DNA damage compared with preclinical studies [16, 21]. This correlates with essentially no pH2AX changes seen in samples at that dose level.

Efficacy

Four patients had non-measurable disease at baseline and were not evaluable for efficacy analyses. Of the remaining 38 patients who were evaluable, two achieved a partial objective tumor response (AZD7762 6 mg/gemcitabine 750 mg/m2 and AZD7762 9 mg cohort). Both patients had non-small-cell lung cancer and neither had received prior gemcitabine treatment. A best response of stable disease for ≥6–<12 weeks was reported for five patients (AZD7762 6 mg/gemcitabine 750 mg/m2, AZD7762 14 mg and AZD7762 30 mg cohorts, n = 1 patient per cohort, and AZD7762 40 mg cohort n = 2 patients) and four patients recorded stable disease for ≥12 weeks (AZD7762 6 mg/gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2, AZD7762 14 mg, AZD7762 32 mg and AZD7762 40 mg cohorts, n = 1 patient per cohort). Disease progression was reported as best response in 20 patients; seven were not evaluable (no post-baseline scan).

Discussion

The results presented here allow the following conclusions: first, the MTD of AZD7762 given as a single agent in this cohort of patients was 30 mg, with reversible cardiac events in two patients: one with chest pain and decreased LVEF and a second patient with asymptomatic increase in troponin; second, when combined with gemcitabine at doses >30 mg, nausea and neutropenic fever proved dose limiting; third, peak plasma concentrations at the 30 mg dose (291 ng/ml) are well within a range consistent with modulation of Chk1 activity in vivo, although only minimal increases in pChk1ser345 and pH2AX staining in skin follicles were observed in the 32 mg cohort with no increased staining in other dose cohorts; fourth, no evidence of pharmacological interaction of AZD7762 with the elimination of gemcitabine was noted, or vice versa; and finally, partial objective responses were observed, but only in gemcitabine-naïve patients. In light of this information, and taking into consideration the cardiac toxicities reported both here and in companion studies [22, 23], further development of AZD7762 has been stopped. While this manuscript was in preparation, Seto et al. [23] have reported the results of a Phase I study of AZD7762 in combination with gemcitabine on a similar schedule in Japanese patients. Analogous to the experience reported here, cardiac AEs including bradycardia, hypertension, and a DLT troponin T increase did not support dose escalation beyond 21 mg in that study, generally concordant with the results presented here in US patients.

The basis for AZD7762-induced cardiac toxicity is unknown; although Chk1(−/−) mice experience embryonic lethality [24], there is no obvious cardiac defect. During selectivity screening which formed part of its preclinical evaluation, AZD7762 displayed less than tenfold selectivity for kinases that were generally from the same family as Chk1, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases (CaM kinases) and src-like kinases, with further investigations of cell cycle-related kinases revealing greater selectivity for Chk1 versus CDKs and MAP kinases [16]. Very recently obtained data, however, have revealed the importance of particular CaM kinases in maintaining various aspects of cardiac function including, but not limited to, contractility [25]. In addition, proteomic analyses reveal the importance of CaM signaling to the action of ATPases, recently characterized as ‘critical’ to heart muscle function in zebrafish [26].

The toxicological profile of AZD7762 in preclinical species reveals a mixed picture of cardiovascular changes. In rats, AZD7762 (0.43–150 mg/M2) produced reversible decreases in blood pressure with, in a minority of animals, increases in troponins. In conscious dogs, transient dose-dependent decreases in left ventricular contractility (22 %) have been reported at doses between 5 and 152 mg/M2 with no effects on systolic or diastolic arterial blood pressure (data on file, AstraZeneca). As a result of these preclinical observations, frequent LVEF and troponin monitoring were employed in the current protocol. In addition, the importance of assessing AZD7762-related effects, as well as those due to the combination of AZD7762 with gemcitabine, encouraged the use of ‘cycle 0’ with AZD7762 alone and subsequent ‘cycle 1’ of AZD7762 with gemcitabine, rather than a ‘phase 0’ approach. In both this clinical study and its companion study [22], there was clear evidence of concomitant myocardial ischemia as a DLT, in addition to ‘asymptomatic’ evidence of troponin damage in both companion studies [22, 23].

As evidenced by the use of anthracyclines, clinical oncologists have long accepted the use of overt cardiotoxins that exhibit relatively predictable dose-related AEs but in concert with evidence of irrefutable efficacy. In contrast, the cardiac AE profile of AZD7762 demonstrated acute events that were medically unacceptable across an unpredictable dose range. In the cohort of patients studied here and in the study reported from Japan [23], clear evidence of cardiac toxicity occurred at doses as low as 30 mg, while in the companion study cardiac AEs of a serious nature were not evident until higher doses of AZD7762 were administered [22]. Taken together, the data suggest that a broad and, likely flat, concentration-effect curve of a range of serious cardiovascular AEs would be associated with AZD7762 iv bolus administration in humans. This would render the use of AZD7762 iv bolus impractical in the range of concomitant cardiovascular co-morbidities encountered in the usual oncology population.

Also of importance is whether Chk1 inhibitors will be expected to have a cardiovascular DLT as a class-limiting aspect of their use. In this regard, the recently reported information concerning the Chk1 antagonist SCH 900776 is of interest [27]. While there was evidence of QTc prolongation as a DLT in a population of heavily pretreated leukemia patients treated in the salvage setting with concomitant ‘timed sequential’ cytarabine, the toxicity was reversible and not accompanied by more dire cardiovascular AEs [27]. Importantly, clinically significant responses in a population already previously exposed to cytarabine were observed, along with evidence of clear upregulation of histone 2AX phosphorylation in leukemic blasts [27]. Therefore, from a pharmacological perspective, a detailed characterization of kinases differentially inhibited by both agents may illuminate potentially significant sources for differential cardiovascular toxicity that could be associated with Chk1 antagonists.

Another question that could be considered in relation to our findings is whether the selection of patients with mutated p53 would lead to greater efficacy, even at lower doses, owing to the expected ‘synthetic lethality’ between the p53-mutated state and Chk1 loss or inhibition [12]. Furthermore, Chk1 may have both p53-dependent and p53-non-dependent mechanisms for enhancing DNA-damaging agent sensitivity (e.g., to initiate and maintain DNA replication) [28]. Early-phase studies defining pharmacology and PD might therefore reasonably proceed without requiring a biologically defined population. However, once a Chk1 kinase antagonist with a suitable human toxicity profile is defined, assessing its efficacy in biologically distinct patient subsets will be of great importance to assure its most expeditious testing in populations likely to benefit from this approach to modulating sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents.

References

Weinert TA, Hartwell LH (1988) The RAD9 gene controls the cell cycle response to DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science 241:317–322

Hartwell LH, Weinert TA (1989) Checkpoints: controls that ensure the order of cell cycle events. Science 246:629–634

Wahl GM, Linke SP, Paulson TG, Huang LC (1997) Maintaining genetic stability through TP53 mediated checkpoint control. Cancer Surv 29:183–219

Abraham RT (2001) Cell cycle checkpoint signaling through the ATM and ATR kinases. Genes Dev 15:2177–2196

Zinkel S, Gross A, Yang E (2006) BCL2 family in DNA damage and cell cycle control. Cell Death Differ 13:1351–1359

Lau CC, Pardee AB (1982) Mechanism by which caffeine potentiates lethality of nitrogen mustard. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79:2942–2946

Sausville EA, Johnson J, Alley M, Zaharevitz D, Senderowicz AM (2000) Inhibition of CDKs as a therapeutic modality. Ann N Y Acad Sci 910:207–221

Shapiro GI, Harper JW (1999) Anticancer drug targets: cell cycle and checkpoint control. J Clin Invest 104:1645–1653

Wang Q, Worland PJ, Clark JL, Carlson BA, Sausville EA (1995) Apoptosis in 7-hydroxystaurosporine-treated T lymphoblasts correlates with activation of cyclin-dependent kinases 1 and 2. Cell Growth Differ 6:927–936

Graves PR, Yu L, Schwarz JK, Gales J, Sausville EA, O’Connor PM, Piwnica-Worms H (2000) The Chk1 protein kinase and the Cdc25C regulatory pathways are targets of the anticancer agent UCN-01. J Biol Chem 275:5600–5605

Zhao B, Bower MJ, McDevitt PJ, Zhao H, Davis ST, Johanson KO, Green SM, Concha NO, Zhou BB (2002) Structural basis for Chk1 inhibition by UCN-01. J Biol Chem 277:46609–46615

Wang Q, Fan S, Eastman A, Worland PJ, Sausville EA, O’Connor PM (1996) UCN-01: a potent abrogator of G2 checkpoint function in cancer cells with disrupted p53. J Natl Cancer Inst 88:956–965

Fuse E, Tanii H, Kurata N, Kobayashi H, Shimada Y, Tamura T, Sasaki Y, Tanigawara Y, Lush RD, Headlee D, Figg WD, Arbuck SG, Senderowicz AM, Sausville EA, Akinaga S, Kuwabara T, Kobayashi S (1998) Unpredicted clinical pharmacology of UCN-01 caused by specific binding to human alpha1-acid glycoprotein. Cancer Res 58:3248–3253

Sausville EA, Arbuck SG, Messmann R, Headlee D, Bauer KS, Lush RM, Murgo A, Figg WD, Lahusen T, Jaken S, Jing X, Roberge M, Fuse E, Kuwabara T, Senderowicz AM (2001) Phase I trial of 72-hour continuous infusion UCN-01 in patients with refractory neoplasms. J Clin Oncol 19:2319–2333

Sato S, Fujita N, Tsuruo T (2002) Interference with PDK1-Akt survival signaling pathway by UCN-01 (7-hydroxystaurosporine). Oncogene 21:1727–1738

Zabludoff SD, Deng C, Grondine MR, Sheehy AM, Ashwell S, Caleb BL, Green S, Haye HR, Horn CL, Janetka JW, Liu D, Mouchet E, Ready S, Rosenthal JL, Queva C, Schwartz GK, Taylor KJ, Tse AN, Walker GE, White AM (2008) AZD7762, a novel checkpoint kinase inhibitor, drives checkpoint abrogation and potentiates DNA-targeted therapies. Mol Cancer Ther 7:2955–2966

Mitchell JB, Choudhuri R, Fabre K, Sowers AL, Citrin D, Zabludoff Z, Cook JA (2010) In vitro and in vivo radiation sensitization of human tumor cells by a novel checkpoint kinase inhibitor, AZD7762. Clin Cancer Res 16:2076–2084

AstraZeneca (2011) Global policy: bioethics. http://www.astrazeneca.com/Responsibility/Code-policies-standards/Our-global-policies

Rowland M, Tozer TN (1995) Clinical pharmacokinetics: concepts and applications, 3rd edn. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:205–216

Morgan MA, Parsels LA, Zhao L, Parsels JD, Davis MA, Hassan MC, Arumugarajah S, Hylander-Gans L, Morosini D, Simeone DM, Canman CE, Normolle DP, Zabludoff SD, Maybaum J, Lawrence TS (2010) Mechanism of radiosensitization by the Chk1/2 inhibitor AZD7762 involves abrogation of the G2 checkpoint and inhibition of homologous recombinational DNA repair. Cancer Res 70:4972–4981

Ho AL, Bendell JC, Cleary JM, Schwartz GK, Burris HA, Oakes P, Agbo F, Barker PN, Senderowicz AM, Shapiro G (2011) Phase I, open-label, dose–escalation study of AZD7762 in combination with irinotecan (irino) in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 29(15S):abst 3033

Seto T, Esaki T, Hirai T, Arita S, Nosaki K, Makiyama A, Kometani T, Fujimoto C, Hamatake M, Takeoka H, Agbo F, Shi X (2013) Phase I, dose–escalation study of AZD7762 alone and in combination with gemcitabine in Japanese patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 72:619–627

Takai H, Tominaga K, Motoyama N, Minamishima YA, Nagahama H, Tsukiyama T, Ikeda K, Nakayama K, Nakanishi M, Nakayama K (2000) Aberrant cell cycle checkpoint function and early embryonic death in Chk1(-/-) mice. Genes Dev 14:1439–1447

Erickson JR, He BJ, Grumbach IM, Anderson ME (2011) CaMKII in the cardiovascular system: sensing redox states. Physiol Rev 91:889–915

Doganli C, Kjaer-Sorensen K, Knoeckel C, Beck HC, Nyengaard JR, Honore B, Nissen P, Ribera A, Oxvig C, Lykke-Hartmann K (2012) The alpha 2Na+/K+-ATPase is critical for skeletal and heart muscle function in zebrafish. J Cell Sci 125:6166–6175

Karp JE, Thomas BM, Greer JM, Sorge C, Gore SD, Pratz KW, Smith BD, Flatten K, Peterson KL, Schneider P, Mackey K, Freshwater T, Levis M, McDevitt M, Carraway HE, Gladstone DE, Showel MM, Loechner S, Parry DA, Horowitz JA, Issacs R, Kaufmann SH (2012) Phase I and pharmacologic trial of cytosine arabinoside with the selective checkpoint 1 inhibitor SCH 900776 in refractory acute leukemias. Clin Cancer Res 18:6723–6731

Depamphilis ML, de Renty CM, Ullah Z, Lee CY (2012) “The Octet”: eight protein kinases that control mammalian DNA replication. Front Physiol 3:368

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Judith Ochs, Louise Grochow (both of Astrazeneca, US) and Victor Sandor (Incyte Corporation, US) for their assistance in protocol design and initiation of the study. We are also grateful to The General Clinical Research Center, University of Maryland, US. We thank Zoë van Helmond, PhD from Mudskipper Business Ltd, for medical writing support funded by AstraZeneca.

Conflict of interest

P. LoRusso, M. Carducci and E. Sausville have received research funding and attended advisory boards for AstraZeneca. P. Oakes, A. Senderowicz, P. Barker, S. Zabludoff, R. Knight and F. Agbo are all employees of and own stock in AstraZeneca. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sausville, E., LoRusso, P., Carducci, M. et al. Phase I dose-escalation study of AZD7762, a checkpoint kinase inhibitor, in combination with gemcitabine in US patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 73, 539–549 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-014-2380-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-014-2380-5