Abstract

Data on clinical features and outcome in pediatric follicular lymphoma (pFL) are scarce. The aim of this retrospective study including 13 EICNHL and/or i-BFM study group members was to assess clinical characteristics and course in a series of 63 pFL patients. pFL was found to be associated with male gender (3:1), older age (72 % ≥10 years old), low serum LDH levels (<500 U/l in 75 %), grade 3 histology (in 88 %), and limited disease (87 % stage I/II disease), mostly involving the peripheral lymph nodes. Forty-four out of sixty-three patients received any polychemotherapy and 1/63 rituximab only, while 17/63 underwent a “watch and wait” strategy. Of 36 stage I patients, 30 had complete resections. Only one patient relapsed; 2-year event-free survival and overall survival were 94 ± 5 and 100 %, respectively, after a median follow-up of 2.2 years. Conclusively, treatment outcome in pFL seems to be excellent with risk-adapted chemotherapy or after complete resection and an observational strategy only.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While follicular lymphoma (FL) accounts for 25 % of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (NHL) in adulthood, it rarely occurs in children and adolescents (<2 % of cases) [1–4]. FL is recognized as a unique histopathological entity in the pediatric age group, with a high proportion, having grade 3 morphology, and no BCL2-rearrangement [1, 3, 5]. Moreover, while most adult patients present with disseminated disease at initial diagnosis, children usually present with localized disease often confined to the peripheral lymph nodes only [1, 3, 6, 7]. Optimal treatment of pediatric FL (pFL) has not yet been defined, and therapeutic strategies differ considerably with some groups applying intensive B cell NHL-type chemotherapy according to the stage of disease, others relying on CHOP-like cycles ± rituximab and others favoring a “watch and wait” strategy after complete resection for at least BCL2–negative pFL [3, 6–12]. Regardless of the type of therapy, cure rates approach 90 % [3, 6, 8–10, 12]. Nevertheless, systematic data are scarce regarding clinical, biological, and outcome data in children and adolescents with FL. Thus, the two largest consortia in childhood NHL, the European Intergroup for Childhood NHL (EICNHL) and the international Berlin–Frankfurt–Münster (i-BFM) group, designed a retrospective multinational study on this rare B cell NHL. Herein, we report on the characteristics and outcome of 63 patients with pFL included in this analysis.

Patients and methods

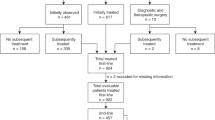

Between May and December 2011, we performed an international survey of pFL, including only patients with nationally centrally reviewed histopathology from 13 EICNHL and/or i-BFM study group members. The survey included questions on demographics and disease (age, gender, sites of involvement, stage of disease, pretherapeutic lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level) as well as on treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy) and outcome (date of remission, relapse, death, last follow-up). After 2000, a total of 63 children and adolescents up to 18 years old diagnosed with pFL were identified in the respective countries. The diagnosis was based on morphological and immunophenotypic criteria according to the World Health Organization classification [13]. Staging procedures as well as therapy protocols applied to the patients are described in detail elsewhere [3, 11, 14–19]. Most, if not all, patients were treated according to national treatment guidelines. All patients were treated, with informed consent from the patients, patient's parents, or legal guardians. Studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approval was delivered by the ethic committees. Event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) were estimated with Kaplan–Meier curves.

Results and discussion

Among the 63 patients, the male to female ratio was 3:1, and median age was 13.0 years (range 1.4–17.1 years), with 45/63 patients (72 %) ≥10 years old. The median pretherapeutic serum LDH level was 252 U/l (range 93–550 U/l), with 47/63 patients (75 %) having levels <500 U/l. Thirty-six out of sixty-three (57 %) had stage I (30 (83 %) with initial complete resection), 19 (30 %) stage II (2 (11 %) with initial complete resection), six (10 %) stage III, and two (3 %) children had stage IV disease, according to the St. Jude staging system, resulting in 54/63 patients (87 %) with limited stage I/II disease [19]. Details on patient characteristics and sites of involvement are summarized in Table 1, showing that 50/63 patients (79 %) had peripheral lymph node involvement. Histopathological grading was available in 48/63 patients (76 %), demonstrating grade 1 or 2 morphology in 6/48 (12.5 %) and grade 3 morphology in 42/48 patients (87.5 %). Nine out of forty-two patients (21 %) with grade 3 pFL had components of diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Forty-four out of sixty-three patients (70 %) received any polychemotherapy and one (2 %) rituximab only, while 17 (26 %) underwent a “watch and wait” strategy (all with initial complete resection) (Table 1). In one patient (2 %), the type of therapy received could not be retrieved. Of the 38/44 patients with available information, all but two patients received low or intermediate risk B cell NHL-type therapy (Table 1). Only 1/63 patients (2 %) relapsed (after “watch and wait”), and none of the patients died from the disease itself or therapy-related toxicity. The 2-year EFS and OS rates were 94 ± 5 and 100 % (Fig. 1), respectively, after a median follow-up of 2.2 years (range 0.19–8.71 years).

To our knowledge, this report including 63 patients with centrally reviewed pFL covering a time period >10 years represents by far the largest series of pFL in childhood and adolescence reported to date. Although the analysis has been conducted retrospectively, was not population-based, and patients were not treated according to a common protocol or strategy, it allows several insights into the clinical presentation and outcome of pFL patients and thus may have important implications on the future management of this indolent disease. Our data convincingly show that pFL is usually associated with male gender (3:1), older age (40 % 10–15 years, 32 % ≥15 years old), low serum LDH levels (<500 U/l in 75 %), and limited disease (87 % with stage I/II disease), mostly involving the peripheral lymph nodes. However, as we identified stage III/IV patients, initial diagnostic work-up should always follow the St. Jude staging system [19]. Due to its rarity, only few case reports and series on pFL have been published so far with patient numbers ranging from 4–25 [3, 6, 8–10, 12]. Most of the reports demonstrated similar findings concerning the initial clinical and laboratory features of pFL [1, 3, 6, 8–10, 12].

Nonetheless, we demonstrated that in contrast to FL in adults which is usually of low-grade morphology and not curable with diverse treatment approaches, pFL is frequently associated with grade 3 morphology and has a very good outcome after limited chemotherapy or complete resection followed by a “watch and wait” strategy [3, 11, 20]. Chemotherapy was performed according to stage-adapted protocols of the NHL-BFM (n = 27), AIEOP (n = 3), LMB (n = 2), JACLS (n = 5), and UKCCSG (n = 1) studies and with CHOP (n = 5) and CVP (n = 1) cycles, respectively [6, 15–18, 21, 22].

Importantly, neither higher histological grading nor initial components of DLBCL were associated with an unfavorable prognosis. In addition, of the 32 patients with initial complete resection (including 30/36 stage I patients), 17 (53 %) children had no further treatment with only one relapse (local), suggesting no systemic disease in localized pFL. The excellent overall outcome of our cohort of FL patients is comparable to the results published in the literature, showing that pediatric stage-adapted B cell NHL-type chemotherapy and CHOP-like cycles ± rituximab are effective in (in)completely resectable disease [1, 3, 6, 8–10, 12, 22]. However, the exact role of complete resection and observation has not been validated until yet. Thus, future clinical trials should aim to establish the least amount of effective (chemo) therapy necessary for cure of pFL. As almost all cycles of chemotherapy used for pediatric B cell NHL include anthracyclines, alkylating agents, and intrathecal therapy, low intensity chemotherapy for pFL should be ideally free of the latter components usually carrying the risk for acute and long-term toxicity [16–18, 23]. A recent study in pediatric early-stage nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin's lymphoma may serve as a paradigm, as it has shown that low intensity chemotherapy is successful in noncompletely resectable disease, while more toxic treatment blocks applied for classic Hodgkin's lymphoma can be reserved for relapse [24].

Notably, there are several limitations when analyzing data from a multinational retrospective survey on a very rare lymphoma subtype, all of which necessitate further evaluation in well-defined prospective trials. As such, we were unable to report on genetic studies, minimal residual disease screening, and in particular on how and why the decision was taken by the responsible physicians to follow a “watch and wait strategy” or chemotherapy in completely resected disease.

Nevertheless, based on the data gained from our unique survey on pFL, we concluded that in the case of complete resections in carefully evaluated stage I patients a “watch and wait” strategy might be possible. However, we suggest that patients are only candidates for complete surgical resection if the operation can be performed easily and safely, and, most importantly, without any functional impairment. In all other patients, initial surgery should include the least invasive procedure to establish the diagnosis followed by limited chemotherapy. Given the difficulties in differentiating pFL from reactive lymphadenopathy, evaluation by an experienced hematopathologist is highly recommended before starting any therapy [13]. As children with nonresectable pFL had an excellent outcome with multidrug chemotherapy, which is associated with acute and long-term toxicity, multinational controlled trials have to be performed, taking genetics (BCL2, BCL6, IGH, C-MYC) into account, to clearly establish not only that no chemotherapy is a safe approach in stage I patients with complete resection, but low intensity chemotherapy ± monoclonal antibodies is sufficient for patients with noncompletely resectable disease [7, 21–23, 25, 26].

References

Agrawal R, Wang J (2009) Pediatric follicular lymphoma: a rare clinicopathologic entity. Arch Pathol Lab Med 133:142–146

Anderson JR, Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD (1998) Epidemiology of the non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: distributions of the major subtypes differ by geographic locations. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma classification project. Ann Oncol 9:717–720

Oschlies I, Salaverria I, Mahn F, Meinhardt A, Zimmermann M, Woessmann W, Burkhardt B, Gesk S, Krams M, Reiter A, Siebert R, Klapper W (2010) Pediatric follicular lymphoma—a clinicopathological study of a population-based series of patients treated within the non-Hodgkin's lymphoma-Berlin–Frankfurt–Munster (NHL-BFM) multicenter trials. Haematologica 95:253–259

Kansal R, Singleton TP, Ross CW, Finn WG, Padmore RF, Schnitzer B (2002) Follicular Hodgkin lymphoma: a histopathologic study. Am J Clin Pathol 117:29–35

Louissaint A Jr, Ackerman AM, Dias-Santagata D, Ferry JA, Hochberg EP, Huang MS, Iafrate AJ, Lara DO, Pinkus GS, Salaverria I, Siddiquee Z, Siebert R, Weinstein HJ, Zukerberg LR, Harris NL, Hasserjian RP (2012) Pediatric-type nodal follicular lymphoma: an indolent clonal proliferation in children and adults with high proliferation index and no BCL2 rearrangement. Blood 120:2395–2404

Atra A, Meller ST, Stevens RS, Hobson R, Grundy R, Carter RL, Pinkerton CR (1998) Conservative management of follicular non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in childhood. Br J Haematol 103:220–223

Kumar R, Galardy PJ, Dogan A, Rodriguez V, Khan SP (2011) Rituximab in combination with multiagent chemotherapy for pediatric follicular lymphoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 57:317–320

Finn LS, Viswanatha DS, Belasco JB, Snyder H, Huebner D, Sorbara L, Raffeld M, Jaffe ES, Salhany KE (1999) Primary follicular lymphoma of the testis in childhood. Cancer 85:1626–1635

Lones MA, Raphael M, McCarthy K, Wotherspoon A, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, Ramsay AD, Maclennan K, Cairo MS, Gerrard M, Michon J, Patte C, Pinkerton R, Sender L, Auperin A, Sposto R, Weston C, Heerema NA, Sanger WG, von Allmen D, Perkins SL (2012) Primary follicular lymphoma of the testis in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 34:68–71

Lorsbach RB, Shay-Seymore D, Moore J, Banks PM, Hasserjian RP, Sandlund JT, Behm FG (2002) Clinicopathologic analysis of follicular lymphoma occurring in children. Blood 99:1959–1964

McNamara C, Davies J, Dyer M, Hoskin P, Illidge T, Lyttelton M, Marcus R, Montoto S, Ramsay A, Wong WL, Ardeshna K (2012) Guidelines on the investigation and management of follicular lymphoma. Br J Haematol 156:446–467

Pinto A, Hutchison RE, Grant LH, Trevenen CL, Berard CW (1990) Follicular lymphomas in pediatric patients. Mod Pathol 3:308–313

Murphy SB, Fairclough DL, Hutchison RE, Berard CW (1989) Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas of childhood: an analysis of the histology, staging, and response to treatment of 338 cases at a single institution. J Clin Oncol 7:186–193

Amos Burke GA, Imeson J, Hobson R, Gerrard M (2003) Localized non-Hodgkin's lymphoma with B cell histology: cure without cyclophosphamide? A report of the United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group on studies NHL 8501 and NHL 9001 (1985–1996). Br J Haematol 121:586–591

Fujita N, Kobayashi R, Takimoto T, Nakagawa A, Ueda K, Horibe K (2011) Results of the Japan Association of Childhood Leukemia Study (JACLS) NHL-98 protocol for the treatment of B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and mature B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. Leuk Lymphoma 52:223–229

Gerrard M, Cairo MS, Weston C, Auperin A, Pinkerton R, Lambilliote A, Sposto R, McCarthy K, Lacombe MJ, Perkins SL, Patte C (2008) Excellent survival following two courses of COPAD chemotherapy in children and adolescents with resected localized B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: results of the FAB/LMB 96 international study. Br J Haematol 141:840–847

Pillon M, Di Tullio MT, Garaventa A, Cesaro S, Putti MC, Favre C, Lippi A, Surico G, Di Cataldo A, D'Amore E, Zanesco L, Rosolen A (2004) Long-term results of the first Italian Association of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology protocol for the treatment of pediatric B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (AIEOP LNH92). Cancer 101:385–394

Woessmann W, Seidemann K, Mann G, Zimmermann M, Burkhardt B, Oschlies I, Ludwig WD, Klingebiel T, Graf N, Gruhn B, Juergens H, Niggli F, Parwaresch R, Gadner H, Riehm H, Schrappe M, Reiter A (2005) The impact of the methotrexate administration schedule and dose in the treatment of children and adolescents with B cell neoplasms: a report of the BFM Group Study NHL-BFM95. Blood 105:948–958

Murphy SB (1980) Classification, staging, and end results of treatment of childhood non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: dissimilarities from lymphomas in adults. Semin Oncol 7:332–339

Kridel R, Sehn LH, Gascoyne RD (2012) Pathogenesis of follicular lymphoma. J Clin Invest 122:3424–3431

Marcus R, Imrie K, Solal-Celigny P, Catalano JV, Dmoszynska A, Raposo JC, Offner FC, Gomez-Codina J, Belch A, Cunningham D, Wassner-Fritsch E, Stein G (2008) Phase III study of R-CVP compared with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone alone in patients with previously untreated advanced follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 26:4579–4586

Perkins SL, Gross TG (2011) Pediatric indolent lymphoma–would less be better? Pediatr Blood Cancer 57:189–190

Goldman S, Smith L, Anderson JR, Perkins S, Harrison L, Geyer MB, Gross TG, Weinstein H, Bergeron S, Shiramizu B, Sanger W, Barth M, Zhi J, Cairo MS (2012) Rituximab and FAB/LMB 96 chemotherapy in children with Stage III/IV B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a Children's Oncology Group report. Leukemia

Shankar A, Hall GW, Gorde-Grosjean S, Hasenclever D, Leblanc T, Hayward J, Lambilliotte A, Daw S, Perel Y, McCarthy K, Lejars O, Coulomb A, Oberlin WO, Wallace WH, Landman-Parker J (2012) Treatment outcome after low intensity chemotherapy (CVP) in children and adolescents with early stage nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin's lymphoma—an Anglo–French collaborative report. Eur J Cancer 48:1700–1706

Marcus R, Imrie K, Belch A, Cunningham D, Flores E, Catalano J, Solal-Celigny P, Offner F, Walewski J, Raposo J, Jack A, Smith P (2005) CVP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CVP as first-line treatment for advanced follicular lymphoma. Blood 105:1417–1423

Meinhardt A, Burkhardt B, Zimmermann M, Borkhardt A, Kontny U, Klingebiel T, Berthold F, Janka-Schaub G, Klein C, Kabickova E, Klapper W, Attarbaschi A, Schrappe M, Reiter A (2010) Phase II window study on rituximab in newly diagnosed pediatric mature B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and Burkitt leukemia. J Clin Oncol 28:3115–3121

Acknowledgments

We thank all participating institutions and physicians for their support of the study. This EICNHL and i-BFM paper was written on behalf of the Berlin–Frankfurt–Münster (BFM) study group (Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Czech Republic), Associazione Italiana Ematologia Oncologia Pediatrica (AIEOP), UK Children's Cancer and Leukemia study group (CCLG), Nordic Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology (NOPHO), Belgian Society of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Dutch Childhood Oncology Group (DCOG), Hungarian Pediatric Oncology Network, Japanese Pediatric Leukemia/Lymphoma study group (JPLSG), and Hong Kong Pediatric Hematology and Oncology study group (HKPHOSG). This work was supported by the Cancer Research UK, the Forschungshilfe Station Peiper (BFM Germany), the St. Anna Kinderkrebsforschung (BFM Austria), the Czech Ministry of Health supported projects for conceptual development of research organization 00064203 and 65269705 (BFM Czech Republic), the Associazione Italiana Contro le Leucemie and Fondazione Citta della Speranza (AIEOP), and the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (JPLSG).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Attarbaschi, A., Beishuizen, A., Mann, G. et al. Children and adolescents with follicular lymphoma have an excellent prognosis with either limited chemotherapy or with a “watch and wait” strategy after complete resection. Ann Hematol 92, 1537–1541 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-013-1785-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-013-1785-2