Abstract

Primary gastric lymphomas are the most common extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and are divided into indolent (low grade) and aggressive (high grade) types. They are mainly the disease of middle age, with a male predominance reported by most of the studies. For several years, surgery played a central role in diagnosis, staging, and treatment of this entity, yet recently there has been a move away from a surgical approach to conservative treatment. To determine the role of surgery as the initial treatment modality, we performed this retrospective single-center research on 245 patients with primary gastric lymphoma who were treated according to our protocol between 1990 and 2003. The patients’ characteristics, distribution of histological types, treatment results, and disease-specific survival were followed. According to the histology, 59.2% had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLCL), 26.1% MALT lymphoma, 9.8% mixed lymphoma (indolent and aggressive at the same time), while other types were infrequent. In total, 161 patients (65.7%) were treated with surgical resection as the initial treatment, which was then followed or not by additional therapy (chemotherapy, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, radiotherapy) depending on the histological type of lymphoma and the extent of residual disease after surgery. In 84 patients (34.3%), the treatment approach was conservative. The selection of treatment (chemotherapy, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, radiotherapy or Helicobacter pylori eradication only) was based on the histological type of lymphoma, considering also the patients’ physical condition. The disease-specific survival in the group of patients who underwent surgery was statistically significantly better than in patients who were treated conservatively (p=0.049). At 5 years, it was 96.9% for the group treated with surgery and 89.8% in patients treated conservatively. However, the results were biased, as the patients who were treated conservatively were either in a worse performance status or presented with a more extensive disease. Similarly, in the DLCL type the disease-specific survival was better in the surgically treated group (97.2%) than in the conservatively treated patients (89.2%). The difference was barely significant (p=0.046) and again the results have to be considered with caution due to the selection of patients in a worse performance status or with a more extensive disease for conservative treatment. In the MALT lymphoma and mixed lymphoma types, there were no differences in the disease-specific survival between both treatment groups. Regarding the statement that for conservative treatment patients were selected who were unsuitable for the resection on account of concomitant diseases or due to the fact that the process was inoperable, we believe that the conservative approach gives comparable outcomes to the approach including initial surgery. The existing evidence thus no longer justifies surgery as the standard initial treatment and preference should be given to conservative treatment approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal tract lymphomas are predominately of NonHodgkin’s (NHL) type. They are rather rare and account for 4 to 20% of all NHL cases. At the same time, the gastrointestinal tract is the most common extranodal site of lymphoma presentation, with the stomach being affected most frequently. Primary gastric lymphomas thus represent 55 to 65% of all gastrointestinal lymphomas [6, 7, 9, 13, 20]. Primary gastric lymphomas are mainly the disease of middle age, with a male predominance reported by most of the studies. The calculated incidence rate is given as 0.21 per 100,000 and has been steadily increasing in the past two decades [11, 21, 23, 24]. Predominant symptoms at presentation include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and bleeding [6]. The antrum of the stomach is affected most frequently, followed by the middle third and the fundus; only in exceptional cases is the whole stomach affected [1, 8].

According to pathological classification, primary gastric lymphomas comprise indolent (or low-grade) and aggressive (or high-grade) types. Low-grade lesions nearly always arise from mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) secondary to chronic Helicobacter pylori infection and disseminate slowly. High-grade lesions may develop from a low-grade MALT component or may arise de novo. They can spread to other sites (lymph nodes, adjacent organs, and distant sites) more quickly than low-grade lesions [14]. Gastric lymphomas present more frequently as high-grade malignancy than low-grade disease [11, 21, 23, 24, 30]. Nearly 60% of gastric lymphomas are high-grade lesions with or without a low-grade MALT component. These lymphomas can be treated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy according to the extent of the disease. Surgery, which used to be the initial treatment for gastric lymphoma in the past, is now often reserved for patients with localized, residual disease after nonsurgical therapy or for rare patients with complications. About 40% of gastric lymphomas are low-grade, and nearly all are classified as MALT lymphomas. For low-grade MALT lymphomas confined to the gastric wall, H. pylori eradication is highly successful in causing lymphoma regression. More advanced low-grade lymphomas or those that do not regress with antibiotic therapy can be treated with combinations of H. pylori eradication, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Surgery is again reserved for residual disease and for complications [30].

With this retrospective single-center research, we tried to evaluate a rather large series of patients with primary gastric lymphoma, who were treated according to our protocol in regard to the patients’ characteristics, distribution of histological types, treatment results, and disease-specific survival to determine the role of surgery as the initial treatment modality.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study includes 245 patients with primary gastric lymphomas diagnosed between January 1990 and December 2003 at the Institute of Oncology Ljubljana. Patients were considered to have primary gastric lymphoma, according to the criteria of Isaacson [14]. Details of presenting history, physical examination, staging investigation, treatment, and outcome were taken from patient records. Of 245 patients evaluated, 145 had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLCL) (59.2%), 64 MALT lymphoma (26.1%), 24 mixed lymphoma (indolent and aggressive at the same time) (9.8%), seven unclassified B-cell lymphoma (2.9%), one patient had follicular lymphoma (0.4%) and one Burkitt’s lymphoma (0.4%), while three patients had peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) (1.2%) (Fig. 1).

Staging procedure was performed according to the recommendations of the International Workshop for gastrointestinal tract lymphomas [22] on the basis of history, physical examination, blood tests, chest radiograph, abdominal ultrasound (in a minority of patients abdominal (chest) computed tomography scans), gastroscopic biopsies (alternatively surgical staging in patients undergoing surgery), bone marrow biopsy, and, in some patients, endoscopic ultrasound. Histological diagnosis was confirmed by skilled hematopathologists.

According to the then protocol of our Institute, the patients were treated as follows. Patients with aggressive lymphomas primarily underwent surgical resection. In case of microscopically radical resection, they received five cycles of CHOP regimen, while patients with microscopic or macroscopic residual disease received five cycles of CHOP regimen followed by involved field radiotherapy with 21 Gy (30 Gy for those with macroscopic residual disease and a partial response to chemotherapy). Only patients who refused surgery, or were unsuitable for the resection (either on account of concomitant diseases or due to the fact that the process was inoperable) were treated conservatively, i.e., with six cycles of CHOP regimen followed by involved field radiotherapy with 21 Gy (complete responders) or 30 Gy (partial responders). Modifications of this procedure (e.g., other chemotherapy regimens) were applied in some patients on the basis of their individual physical condition or the type of lymphoma. Patients with histologically unclassified lymphomas were treated as above. Patients with indolent lymphomas were also primarily treated with surgical resection. In case of microscopically radical resection, they received no further treatment, while patients with microscopic or macroscopic residual disease underwent radiation treatment (involved field radiotherapy) with 30 Gy. Again, only patients who refused surgery, or were unsuitable for the resection were treated conservatively, i.e., with involved field radiotherapy with 30 Gy. Another exception to this rule was the patients with Helicobacter pylori-positive MALT lymphomas who were in histologically confirmed complete remission after the eradication treatment.

In total, 161 patients (106 with DLCL, 33 with MALT lymphoma, 19 with mixed lymphoma, two with unclassified B lymphoma, one with PTCL) were treated with surgical resection, while in 84 patients (39 with DLCL, 31 with MALT lymphoma, one with follicular and one with Burkitt’s lymphoma, five with mixed lymphoma, five with unclassified B lymphoma, two with PTCL) the treatment was conservative. In the group of patients treated with resection, 119 patients underwent chemotherapy treatment—115 patients were treated with CHOP regimen, one with COP, one with Chlorambucil, one with chemotherapy according to BFM protocol, and one patient received another type of chemotherapy. Ninety-four patients from this group were treated with radiotherapy as a part of the first treatment. Twenty-eight patients were treated with surgery only—six of them had DLCL and either refused further treatment or their condition was too poor to allow further treatment, two of them with mixed lymphoma were also unable to tolerate further treatment, while 20 patients with MALT lymphoma needed no further treatment according to radical resection of the disease. In the group of 84 patients who were not treated surgically, 46 patients received chemotherapy—40 patients were treated with CHOP regimen, two with COP, one with chemotherapy according to BFM protocol, and three patients received other types of chemotherapy. Sixty-four patients were treated with radiotherapy, while 13 patients neither received chemotherapy nor were irradiated. One of these 13 patients who had a mixed lymphoma and one with MALT lymphoma refused any kind of treatment, one with DLCL and nine with MALT lymphoma were treated just with Helicobacter pylori eradication, and one patient with unclassified lymphoma was unable to tolerate any kind of treatment. Treatment stratification in the three most common subtypes of primary gastric lymphoma (DLCL, MALT lymphoma, mixed lymphoma) is given in Table 1.

Parameters that were analyzed were treatment response according to defined criteria [4], and disease-specific survival (patients who died of causes other than lymphoma were taken as censored). Continuous data are given as median and the respective range. Survival curves were done by applying the Kaplan–Meier method and the comparison between groups was performed through log-rank test.

Results

The group of patients included in the study consisted of 115 men and 130 women. The median age was 61.5 years (range 17 to 89 years) for the whole group, and 58.5 years (range 22 to 88 years) and 64.4 years (range 17 to 89 years) for the men and women population, respectively. The median observation period was 74.3 months (range 1.2 to 182.2 months).

The distribution of patients according to the histological types of lymphoma is given in the Materials and methods section and presented in Fig. 1.

One hundred and twenty-four patients (50.6%) had stage I disease and 121 (49.4%) had stage II disease (Table 2).

In total, 76 patients died (31.0%), 162 patients are still alive (66.1%), and seven patients were lost from observation (2.9%). Of those who died, only 15 patients died of lymphoma, while 61 deaths were on account of reasons different from lymphoma. The disease-specific survival was 94.5% at 5 years (Fig. 2).

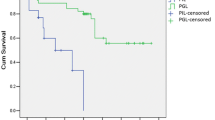

The disease-specific survival in the group of patients who underwent surgery was statistically significantly better than in patients who were treated conservatively (p=0.049). At 5 years, it was 96.9% for the group treated with surgery and 89.8% in patients treated conservatively (Fig. 3).

Treatment response and disease-specific survival were evaluated separately for patients with DLCL, MALT lymphoma, and mixed lymphoma, but not in other histological types of gastric lymphomas, due to a rather small number of patients in each group.

DLCL

This group included 145 patients of whom 61 had stage I disease and 84 stage II disease. One hundred and six patients (73.1%) were primarily treated with surgery, while 39 patients (26.9%) underwent conservative treatment.

Of the 106 patients treated with resection, six patients received no further treatment (three patients refused additional treatment and three patients were unable to tolerate it) and 100 patients were treated with chemotherapy (97 CHOP regimen, three patients other regimens). In 65 patients, the chemotherapy treatment was followed by involved field radiotherapy due to microscopic or macroscopic residual disease (Table 1). Complete response was achieved in 104 patients and partial response in two patients (in one patient treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, but who failed to finish primary treatment, and in one patient treated with surgery only). Three patients from this group died of lymphoma—the patient who failed to finish primary treatment and progressed during primary treatment and two patients who relapsed from complete remission.

Of the 39 patients treated conservatively, 37 patients received chemotherapy (34 CHOP regimen, three patients other regimens), one patient was treated with involved field radiotherapy (30 Gy) and another patient received eradication treatment for Helicobacter pylori only. In 34 out of 37 patients treated with chemotherapy, involved field radiotherapy was performed following systemic treatment (Table 1). Complete response was reached in 34 patients (including both patients who received no chemotherapy), partial response in two patients, no change of the disease in one patient, while progression was observed in two patients. In the five patients who did not achieve complete remission, the primary treatment was either inadequate (dose reductions of chemotherapy drugs, premature termination of chemotherapy) or was not finished (one patient died of massive bleeding during the chemotherapy). In total, three patients died of progressive lymphoma and one of treatment complication, while one patient with progressive lymphoma died of unrelated cause.

The disease-specific survival in the group of patients who underwent surgery was statistically significantly better than in patients who were treated conservatively (p=0.046). At 5 years, it was 97.2% for the group treated with surgery and 89.2% in patients treated conservatively (Fig. 4).

MALT lymphoma

This group included 64 patients of whom 47 had stage I disease and 17 stage II disease. Thirty-three patients (51.6%) were treated with surgery, while 31 patients (48.4%) underwent conservative treatment.

Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection was confirmed in 26 patients, seven patients were negative for HP, and in 31 patients the HP status was not determined. In all 26 patients positive for HP, eradication treatment was performed—which was the only treatment in nine patients, but was followed by surgery in seven patients, by involved field radiotherapy in six patients, and by surgery plus radiotherapy in four patients.

Of the 33 patients treated with resection, 20 patients received no further treatment (due to microscopically radical resection) and 13 patients were treated with involved field radiotherapy (Table 1). Complete remission was achieved in all 33 patients, yet two patients relapsed from complete remission and eventually died of lymphoma.

Of the 31 patients who were not treated with resection, one older patient (in whom the HP status was not determined) underwent no treatment at all, nine patients received eradication treatment for HP, one patient chemotherapy according to CHOP regimen followed by involved field radiotherapy, and 20 patients were treated with involved field radiotherapy (30 Gy) (Table 1). Complete remission was achieved in 29 patients, partial remission in one patient and stable disease in the patient who received no treatment. Only one patient died of progressive lymphoma after having relapsed from complete response.

The disease-specific survival in the group of patients who underwent surgery did not differ from the survival in the group of patients who were treated conservatively (p=0.758). At 5 years, it was 100% for the group treated with surgery and 96.0% in patients treated conservatively (Fig. 5).

Mixed lymphoma

This group included 24 patients of whom 11 had stage I disease and 13 stage II disease. Nineteen patients (79.2%) were treated with surgery, while five patients (20.8%) underwent conservative treatment.

Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection was confirmed in eight patients, five patients were negative for HP, and in 11 patients the HP status was not determined. In five patients positive for HP, eradication treatment was performed—which was followed by surgery and CHOP therapy in one patient, by surgery, CHOP and radiotherapy in two patients, by CHOP therapy in one patient, and by radiotherapy in one patient. The three patients who had no eradication treatment (despite HP positive status) were treated with resection and CHOP therapy, which was followed by radiotherapy in two patients.

Of the 19 patients treated with resection, one older patient received no further treatment and 18 patients were treated with chemotherapy (17 CHOP regimen, one patient another regimen). In 12 patients, the chemotherapy treatment was followed by involved field radiotherapy due to microscopic or macroscopic residual disease (Table 1). Complete remission was achieved in all 19 patients, and there were no deaths from lymphoma in this group.

Of the five patients who were not treated with resection, three patients received chemotherapy (2 CHOP regimen, one patient another regimen), one patient was treated with involved field radiotherapy (30 Gy) only and another patient refused any kind of treatment. In two out of three patients treated with chemotherapy, involved field radiotherapy was performed following systemic treatment (Table 1). Complete response was achieved in three patients, partial response in one patient who was treated just with CHOP therapy, while the patient who refused any kind of treatment also refused further evaluation, but is still alive 7 years after the diagnosis of mixed lymphoma has been confirmed. Also in this group there were no lymphoma-related deaths.

Discussion

Our study presents the clinical course of 245 patients with primary gastric lymphoma 46.9% of which were men and 53.1% women. Most of the studies otherwise report male predominance in cases of primary gastric lymphoma [5, 16, 17, 26, 29] and in only a few, the opposite was detected [25]. The median age in our study, however, corresponds to previous observations [5, 17, 26, 29].

According to histological types, the proportion of the DLCL (59.2%) in our study was similar to the 59.9% reported by Koch et al. [17], yet our cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with small cell component were classified as mixed lymphomas and represented extra 9.8%. The proportion of MALT lymphomas (26.1%) was thus understandably lower compared to 37.9% reported by Koch et al. The distribution of the rare subtypes (follicular lymphoma 0.4%, Burkitt’s lymphoma 0.4%, peripheral T-cell lymphoma 1.2%) was similar in both studies. On the other hand, seven patients in our study (2.9%) had unclassified B-cell lymphomas on account of the rather poor quality of the endoscopic biopsies.

In the cohort, 50.6% of patients had stage I disease and 49.4% stage II disease. The proportion of patients with stage II disease was the lowest in case of MALT lymphomas (26.6%), increased to 54.2% in mixed lymphomas and even to 57.9% in DLCL, confirming the more aggressive potential of spread in the latter two subtypes. These results are not as extreme as in the study of Ko et al. [15]; however, the frequency of lymph node involvement in our study correlates with the grade of lymphoma.

The disease-specific survival in our study, regardless of the grade and stage of lymphoma, was 94.5% at 5 years—similar percentages were reported by Schmidt et al. (93%) [25] and Gospodarowicz et al. (95.5%) [12]. If the disease-specific 5-year survival was evaluated according to the type of treatment, then the results were better in the group of patients who underwent surgery than in patients who were treated conservatively (96.9% for the group treated with surgery and 89.8% in patients treated conservatively). However, the results were biased, as the patients who were treated conservatively were either in a worse performance status or presented with a more extensive disease. For conservative treatment, actually the patients were selected who were unsuitable for the resection on account of concomitant diseases or due to the fact that the process was inoperable. Thus, by our opinion the conservative approach to treatment gives comparable outcomes to the surgical approach. Another argument for this statement lies in the low significance of difference (p=0.049) between the two rather unequal populations.

If we consider only the group of patients with DLCL, a substantially higher proportion of patients were treated surgically (73.1%) than conservatively (26.9%). Complete responses were achieved in 98.1% of patients treated with surgery and in 87.2% of patients treated conservatively. Again, the treatment results were more than acceptable in the conservatively treated group if we consider their worse performance status and a more extensive disease. Moreover, those patients who did not achieve a complete remission quite often received less than the planned number of chemotherapy cycles or they were applied in reduced doses. Complete response was surprisingly observed also in the patient treated with involved field radiotherapy only and in another patient who only had eradication treatment for Helicobacter pylori. Similar observations were reported by Kocher et al. [18] and Nakamura et al. [19].

When comparing the survival of patients with aggressive lymphomas, one of the largest recent prospective studies [17] reported a 91% cause-specific survival for the surgically treated group and 91.2% for the conservatively treated group at 42 months median time of observation. The disease-specific survivals in our group were 97.2% (surgical treatment) and 89.2% (conservative treatment) at 5 years, respectively. The difference was significant, yet with a low significance of difference (p=0.046), and again the results have to be considered with caution due to the selection of patients in a worse performance status or with a more extensive disease for conservative treatment. The conclusion is equal as above—the conservative approach to treatment gives comparable outcomes to the surgical approach.

The eradication treatment for Helicobacter pylori-positive MALT lymphoma is considered as the primary treatment, as researchers have confirmed that such treatment leads to regression of lymphoma in approximately 80% of patients [27]. However, in our series only 51.5% of MALT lymphoma patients and 54.2% of patients with mixed lymphoma had their HP status determined. Routine determinations of HP status were not performed until 1997. In the MALT group, 78.8% were positive for HP and were all treated with the eradication, while in the mixed lymphoma group, 61.5% (eight patients) were HP-positive, of whom only five patients were treated with eradication. The eradication resulted in only 34.6% of complete responses in the MALT group and was, in all five cases of mixed lymphoma, followed by other treatment modalities due to the associated aggressive component of the lymphoma. The low proportion of complete responses to eradication goes at least partially on account of a too-short-observation period after a successful eradication (lymphoma presence after approximately 6 months was regarded as a treatment failure). At least some of MALT lymphoma patients were, therefore, probably over-treated.

In the group of MALT lymphoma patients, approximately half of the patients (51.6%) underwent surgery, while the others (48.4%) were treated conservatively. The disease-specific survival did not differ between the two groups (p=0.758) and was 100% for the surgical group and 96% in patients treated conservatively. The cause specific survival at 42 months reported by Koch et al. [17] was slightly worse 82.5% for the surgically treated group and 97.2% for the conservatively treated group, respectively. This study, however, included only patients experiencing failure after HP eradication.

The mixed lymphoma group consisted of predominately surgically treated patients (79.2%), similar to the DLCL group. Excellent treatment results were achieved in both surgical and conservative treatment arms, and there were no lymphoma-related deaths in either of the groups. Correspondingly, one of the largest recent prospective studies showed equal cause-specific survivals after 42 months median time of observation [17].

Even though the grade of lymphoma has been identified as an adverse prognostic factor for survival in primary gastric lymphomas [5], the case of the patient from our study who refused any kind of treatment and is still alive 7 years after the diagnosis of mixed lymphoma indicates that sometimes also this type of lymphoma takes a more indolent course.

In conclusion, a conservative approach to treatment of primary gastric lymphomas is also highly effective. According to our analysis as well as other recent studies [2, 3, 10, 16, 17, 28], its outcome equals the outcome of the approach including initial surgery. The existing evidence thus no longer justifies surgery as the standard initial treatment. Preference should be given to conservative treatment approaches.

References

Aozasa K, Ueda T, Kurata A, Kim CW, Inoue M, Matsuura N, Takeuchi T, Tsujimura T, Kadin ME (1988) Prognostic value of histologic and clinical factors in 56 patients with gastrointestinal lymphomas. Cancer 61:309–315

Aviles A, Nambo MJ, Neri N, Huerta-Guzman J, Cuadra I, Alvarado I, Castaneda C, Fernandez R, Gonzalez M (2004) The role of surgery in primary gastric lymphoma: results of a controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg 240:44–50

Brincker H, D’Amore F (1995) A retrospective analysis of treatment outcome in 106 cases of localized gastric non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Danish Lymphoma Study Group, LYFO. Leuk Lymphoma 18:281–288

Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Shipp MA, Fisher RI, Connors JM, Lister TA, Vose J, Grillo-Lopez A, Hagenbeek A, Cabanillas F, Klippensten D, Hiddemann W, Castellino R, Harris NL, Armitage JO, Carter W, Hoppe R, Canellos GP (1999) Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. J Clin Oncol 17:1244–1253

Cogliatti SB, Schmid U, Schumacher U, Eckert F, Hansmann ML, Hedderich J, Takahashi H, Lennert K (1991) Primary B-cell gastric lymphoma: a clinicopathological study of 145 patients. Gastroenterology 101:1159–1170

Crump M, Gospodarowicz M, Shepherd FA (1999) Lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Semin Oncol 26:324–337

d’Amore F, Christensen BE, Brincker H, Pedersen NT, Thorling K, Hastrup J, Pedersen M, Jensen MK, Johansen P, Andersen E et al (1991) Clinicopathological features and prognostic factors in extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Danish LYFO Study Group. Eur J Cancer 27:1201–1208

Dragosics B, Bauer P, Radaszkiewicz T (1985) Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. A retrospective clinicopathologic study of 150 cases. Cancer 55:1060–1073

Fagioli F, Rigolin GM, Cuneo A, Scapoli G, Spanedda R, Cavazzini P, Castoldi G (1994) Primary gastric lymphoma: distribution and clinical relevance of different epidemiological factors. Haematologica 79:213–217

Ferreri AJ, Cordio S, Ponzoni M, Villa E (1999) Non-surgical treatment with primary chemotherapy, with or without radiation therapy, of stage I–II high-grade gastric lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 33:531–541

Fischbach W, Kestel W, Kirchner T, Mossner J, Wilms K (1992) Malignant lymphomas of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Results of a prospective study in 103 patients. Cancer 70:1075–1080

Gospodarowicz MK, Pintilie M, Tsang R, Patterson B, Bezjak A, Wells W (2000) Primary gastric lymphoma: brief overview of the recent Princess Margaret Hospital experience. Res 156:108–115

Gurney KA, Cartwright RA, Gilman EA (1999) Descriptive epidemiology of gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in a population-based registry. Br J Cancer 79:1929–1934

Isaacson P (1994) Gastrointestinal lymphoma. Hum Pathol 25:1020–1029

Ko YH, Han JJ, Noh JH, Ree HJ (2002) Lymph nodes in gastric B-cell lymphoma: pattern of involvement and early histological changes. Histopathology 40:497–504

Koch P, del Valle F, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reers B, Hiddemann W, Grothaus-Pinke B, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Temmesfeld A, Schmitz R, Rube C, Probst A, Jaenke G, Bodenstein H, Junker A, Pott C, Schultze J, Heinecke A, Parwaresch R, Tiemann M (2001) Primary gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: II. Combined surgical and conservative or conservative management only in localized gastric lymphoma-results of the prospective German Multicenter Study GIT NHL 01/92. J Clin Oncol 19:3874–3883

Koch P, Probst A, Berdel WE, Willich NA, Reinartz G, Brockmann J, Liersch R, del Valle F, Clasen H, Hirt C, Breitsprecher R, Schmits R, Freund M, Fietkau R, Ketterer P, Freitag EM, Hinkelbein M, Heinecke A, Parwaresch R, Tiemann M (2005) Treatment results in localized primary gastric lymphoma: data of patients registered within the German multicenter study (GIT NHL 02/96). J Clin Oncol 23:7050–7059

Kocher M, Muller RP, Ross D, Hoederath A, Sack H (1997) Radiotherapy for treatment of localized gastrointestinal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Radiother Oncol 42:37–41

Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Suekane H, Takeshita M, Hizawa K, Kawasaki M, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M, Iida M, Fujishima M (2001) Predictive value of endoscopic ultrasonography for regression of gastric low grade and high grade MALT lymphomas after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gut 48:454–460

Newton R, Ferlay J, Beral V, Devesa SS (1997) The epidemiology of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: comparison of nodal and extra-nodal sites. Int J Cancer 72:923–930

Radaszkiewicz T, Dragosics B, Bauer P (1992) Gastrointestinal malignant lymphomas of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue: factors relevant to prognosis. Gastroenterology 102:1628–1638

Rohatiner A, d’Amore F, Coiffier B, Crowther D, Gospodarowicz M, Isaacson P, Lister TA, Norton A, Salem P, Shipp M et al (1994) Report on a workshop convened to discuss the pathological and staging classifications of gastrointestinal tract lymphoma. Ann Oncol 5:397–400

Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, Aegerter P, Delmer A, Brousse N, Galian A, Rambaud JC (1993) Primary digestive tract lymphoma: a prospective multicentric study of 91 patients. Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes Digestifs. Gastroenterology 105:1662–1671

Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, Rambaud JC (2001) Gastrointestinal lymphoma: prevention and treatment of early lesions. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 15:337–354

Schmidt WP, Schmitz N, Sonnen R (2004) Conservative management of gastric lymphoma: the treatment option of choice. Leuk Lymphoma 45:1847–1852

Shimm DS, Dosoretz DE, Anderson T, Linggood RM, Harris NL, Wang CC (1983) Primary gastric lymphoma. An analysis with emphasis on prognostic factors and radiation therapy. Cancer 52:2044–2048

Stolte M, Bayerdorffer E, Morgner A, Alpen B, Wundisch T, Thiede C, Neubauer A (2002) Helicobacter and gastric MALT lymphoma. Gut 50(Suppl 3):19–24

Taal BG, Burgers JM, van Heerde P, Hart AA, Somers R (1993) The clinical spectrum and treatment of primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the stomach. Ann Oncol 4:839–846

Weingrad DN, Decosse JJ, Sherlock P, Straus D, Lieberman PH, Filippa DA (1982) Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma: a 30-year review. Cancer 49:1258–1265

Yoon SS, Coit DG, Portlock CS, Karpeh MS (2004) The diminishing role of surgery in the treatment of gastric lymphoma. Ann Surg 240:28–37

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. M. Dremelj, L. Zadravec Zaletel, and R. Tomšič from the Department of Radiotherapy of the Institute of Oncology Ljubljana for their cooperation in data evaluation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jezeršek Novaković, B., Vovk, M. & Južnič Šetina, T. A single-center study of treatment outcomes and survival in patients with primary gastric lymphomas between 1990 and 2003. Ann Hematol 85, 849–856 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-006-0172-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-006-0172-7