Abstract

Background

Timely treatment for colorectal cancer (CRC) is a quality indicator in oncological care. However, patients with CRC might benefit more from preoperative optimization rather than rapid treatment initiation. The objectives of this study are (1) to determine the definition of the CRC treatment interval, (2) to study international recommendations regarding this interval and (3) to study whether length of the interval is associated with outcome.

Methods

We performed a systematic search of the literature in June 2020 through MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane databases, complemented with a web search and a survey among colorectal surgeons worldwide. Full-text papers including subjects with CRC and a description of the treatment interval were included.

Results

Definition of the treatment interval varies widely in published studies, especially due to different starting points of the interval. Date of diagnosis is often used as start of the interval, determined with date of pathological confirmation. The end of the interval is rather consistently determined with date of initiation of any primary treatment. Recommendations on the timeline of the treatment interval range between and within countries from two weeks between decision to treat and surgery, to treatment within seven weeks after pathological diagnosis. Finally, there is no decisive evidence that a longer treatment interval is associated with worse outcome.

Conclusions

The interval from diagnosis to treatment for CRC treatment could be used for prehabilitation to benefit patient recovery. It may be that this strategy is more beneficial than urgently proceeding with treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a very common cancer, with 1.8 million new cases registered worldwide in 2018 [1]. The preferred curative treatment option is surgical resection, when indicated in concurrence with (neo)adjuvant therapy. Timely diagnosis and start of treatment have become important goals in optimizing outcomes. The interval between diagnosis and treatment is subject of debate since a prolonged interval may negatively affect oncological outcome. Recommendations regarding length of the CRC treatment interval are incorporated in guidelines in various countries. Those recommendations are often used as an indicator for quality of care and as a surrogate measure of the effectiveness of cancer services [2, 3]. Even so, not meeting the recommendation might result in consequences. For example, in the UK a financial penalty can be imposed by the Clinical Commissioning Group [4, 5]. However, the rationale for these national guidelines is mainly based on consensus and expert opinion only [6, 7].

It is widely accepted that prehabilitation enhances functional capacity prior to CRC treatment and improves postoperative outcome [8,9,10,11,12]. The interval between diagnosis and treatment could thus be used to implement a multimodal prehabilitation program. However, the recommendations for length of the treatment interval may hinder professionals to implement such a program.

In order to find out the definition of the interval upon treatment—“the treatment interval”—and whether this treatment interval could be safely used to implement prehabilitation in CRC, we addressed the following questions:

-

(1)

What is the definition of the CRC treatment interval?

-

(2)

What are the recommendations for CRC treatment interval length included in national guidelines worldwide and are those recommendations feasible?

-

(3)

What is the possible association between outcome and length of the interval between diagnosis and treatment?

Material and methods

Data were collected through a literature review, a web search and a survey among colorectal surgeons worldwide. The literature review provided results for all three research questions. The web search and survey provided additional information about the CRC treatment interval recommendations included in international guidelines discussing timelines (research question 2).

Literature review

A systematic search was performed of the following electronic databases: MEDLINE (1946 to 2020 June 3), EMBASE (1974 to 2020 June 3) and the Cochrane Library (1992 to 2020 June 4) including the following search terms “colorectal neoplasms,” “time-to-treatment,” “time factors” and “waiting lists” (complete search string displayed in Online Resource 1). Titles and abstracts of all records identified by the search were independently screened and assessed for eligibility by two authors (CM and LJ). Articles were deemed eligible if they (1) described CRC either specifically or in combination with other diseases and (2) included a description of the treatment interval defined as any time point in the cancer care pathway until initiation of any form of CRC treatment. The search was restricted to English and Dutch written papers with no limitation in date or study design. Papers were excluded when meeting the following exclusion criteria: interval described with an ending other than treatment, interval described between treatment modalities (e.g., time between neoadjuvant treatment and surgery or between surgery and adjuvant therapy). Full-text articles were retrieved when a paper was considered eligible based on title and abstract or when information was insufficient to determine eligibility. Additionally, bibliographies of included studies were hand-searched to identify any further eligible studies. Any disagreements were discussed. When discordance continued, a third author (GS) arbitrated until consensus was reached. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline was used as guidance for reporting the current systematic review [13].

The following data were extracted independently by CM and LJ using a predefined collection form:

-

General information: first author, publication date, country, journal;

-

Study characteristics: disease(s), study design, sample size, recommendation on length of treatment interval described in the paper, outcomes and results.

Furthermore, specific information was extracted for each research question. For research question 1 regarding the definition of the treatment interval:

-

What time points of the CRC care pathway were used to define the start and end of the treatment interval? For the scope of this question, treatment interval was considered as the time period between any time point in the cancer care pathway until initiation of any form of treatment;

-

Secondly, how were the mentioned time points determined;

-

For data extraction: when two definitions of the treatment interval and/or time point were mentioned in a paper, both definitions were registered. However, in case the paper referred to a hierarchical definition of a time point (e.g., the European Network of Cancer Registries hierarchy [14]), only the upper preferred definition was recorded;

-

A definition of the treatment interval was deemed complete when the following information was provided in the paper: (1) a description of what time points in the cancer care pathway were used to define the start and end of the interval and (2) a description of how these specific time points were determined.

For research question 2 regarding the recommendations on length of the treatment interval included in guidelines:

-

Guideline recommendations and success rate (percentage the aimed target recommended in the guideline was met) described in the paper were only registered when this guideline was actually effectuated in the country the paper originated from.

For research question 3 regarding the association between outcome and length of the interval between diagnosis and treatment:

-

Only the papers using the time point “diagnosis” as start of the treatment interval were included for this question;

-

In case length of the treatment interval was reported for several treatment types, time to surgery was chosen. When length of treatment interval was reported over a period of time, data of the most recent year were extracted. If possible, length of treatment interval without urgent treatments was reported. Finally, when length of treatment interval was described for a standard and an interventional pathway (e.g., direct access colonoscopy versus standard referral), results for the standard pathway were extracted.

Web search

A search on the World Wide Web was performed to complement the overview of international guidelines containing recommendations on length of the CRC treatment interval. The following terms were used to search the web: “colorectal” or “bowel” and “cancer” or “carcinoma” combined with “treatment interval” or “waiting time” and “target,” “recommendation” or “guideline.” Websites of Ministries of Health, cancer societies and colleges of specialists were screened. The web search was restricted to websites written in English or Dutch.

International survey

Since limited countries were represented in the literature and on the web search, additional information on the guidelines in various countries was retrieved by conducting a survey among colorectal surgeons from countries worldwide.

The authors designed a survey based on collected information (Online Resource 2). Intervals, time points and definitions described in the literature or online were used to provide various options regarding the treatment interval. It was arbitrarily decided to use our own network consisting of experts in the field in 33 countries. Based on our information, these surgeons are currently regarded as experts in the field of colorectal oncology by both their peers as well as by the international community. All of them have published studies in international literature and are currently engaged in the treatment of these populations. Moreover, they were willing to act as a representative for their country and provide the required information within a short period of time. Conversely, by randomly approaching national committees or medical societies, we were not convinced that we would receive the proper information in due time. The survey was sent by email, and in case of nonresponse, a reminder was sent after two weeks.

Results

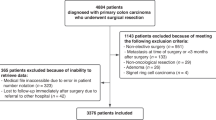

The search in the electronic databases MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Library on June 3–4, 2020 together with the search of bibliographies resulted in 110 included papers. For the first research question, 106 papers were included, 39 papers for question 2 and 30 papers for question 3. There is overlap in those numbers since some papers contained data for more than one research question. The screening and selection process is displayed in a PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1) [15].

-

1.

What is the definition of the CRC treatment interval?

Of the included articles, 106 contained a description of the treatment interval. Five papers included two separate definitions of the treatment interval resulting in 111 intervals described. Time points in the cancer care pathway used to define start and end of the interval were mentioned in all 111 intervals (Table 1). For 63 intervals, a complete definition was provided, containing both definition and determination of time points. The definition and determination of the time points varied widely. The treatment interval generally started with “diagnosis” and often ended with “treatment in general.” Subsequently, date of “diagnosis” was generally determined using date of clinical and/or pathological confirmation and for date of “treatment in general” date of initiation of any treatment was used in the majority of the papers.

-

2.

What are the recommendations for CRC treatment interval length included in national guidelines worldwide and are those recommendations feasible?

Thirty-nine included papers from the literature review described treatment interval recommendations or the lack thereof. Papers also reported the success rate, i.e., percentage the aimed target recommended in the guideline was met.

The survey on treatment interval recommendations was sent to 33 surgeons in 33 countries, and 22 surgeons completed the survey. Data from the survey are only displayed when recommendations differed from the results found through the literature review or web search, or when recommendations for the specific country were unknown.

Guidelines differed between countries regarding the definition of the treatment interval (Table 2). Additionally, the recommendations on the timeline of this interval varied as well, ranging from surgery within two weeks from decision to treat, to treatment within seven weeks from pathological confirmation. Some countries have more than one guideline containing different recommendations on length of the treatment interval, others have no guideline (yet). The majority of the recommendations were based on expert opinion. The recommended targets of these guidelines were met in 21–80%.

-

3.

What is the possible association between outcome and length of the interval between diagnosis and treatment?

In 30 papers, the association between length of the treatment interval (diagnosis—treatment) and outcome in colon, rectal or colorectal cancer was studied (Table 3). The majority of included studies (n = 19) did not find an association between length of CRC treatment interval and outcome. Six papers concluded that a long treatment interval for colonic and/ or rectal cancer treatment is associated with worse outcome than a short treatment interval. Length of the treatment interval described as “long” in those papers ranged from > 31 to > 84 days. Meanwhile, one paper concluded that a long CRC treatment interval is associated with better outcome. Finally, four papers described a U-shaped association with worse outcome when length of the treatment interval was either short or long, compared to an intermediate length. Outcome included surgical outcome (e.g., length of hospital stay, complication rate) or oncological outcome (e.g., tumor stage, recurrence rate, or survival). Survival included 5-year survival, overall survival and disease-specific survival.

Discussion

Based on this study, we conclude that a uniform description of the treatment interval for CRC is absent. Time points defining the start of the interval are not consistently determined. Guidelines and their recommendations for this interval differ widely among countries. Finally, there is no evidence that a short interval between diagnosis and treatment improves oncological outcome.

Heterogeneity in the reporting of cancer care pathway intervals has also been described by other authors [80,81,82,83]. We found that the end of the treatment interval is rather consistent defined as date of initiation of treatment. However, variety in the start of the treatment interval is high ranging from onset of symptoms to definitive diagnosis. Date of diagnosis is often used as start of the interval; however, a clear description of what event represents “diagnosis” is then often unclear and even not specified in nearly one-third of the papers. A clear definition is a necessity since, for example, date of diagnosis and consequently the treatment interval might differ a full week when date of biopsy or date of final pathology report is used [80, 82]. This makes comparison of this quality indicator among institutes difficult. Date of pathological confirmation is a clear and internationally applicable time point in the cancer care pathway and is often used in the literature as date of diagnosis. We therefore recommend the following universal definition for the CRC treatment interval: the interval starts with date of diagnosis, determined by date of pathological confirmation, and the interval ends with the date any primary treatment for CRC is initiated.

Timely diagnosis and treatment is thought to improve oncological outcome. Based on the results of this study, we conclude that length of the CRC treatment interval—starting with date of diagnosis—is not associated with worse outcome. The reported association between a short treatment interval and worse outcome is likely caused by selection; patients with poorer clinical condition or a complication of CRC are generally treated in an emergency setting. Of the papers describing worse outcome with a long treatment interval (including a U-shaped association), only three papers relate a relatively short treatment interval of approximately four weeks to worse outcome [32, 76, 78]. The remaining papers described similar findings with longer intervals ranging from five to 13 weeks. An interval of five weeks from diagnosis to treatment seems safe. Hangaard Hansen et al. even suggested that an interval of eight to nine weeks between diagnosis and treatment is safe regarding the long-term oncological outcomes in colonic cancer [7]. Despite these results, a prolonged treatment interval may worry patients. Healthcare professionals should therefore inform patients optimally regarding the expectations of timeliness in perspective of its meaning to the disease and process [84].

Since timeliness of treatment has become a fundamental objective to ensure quality of care, guidelines including recommendations have been published worldwide. The majority of the recommendations for the treatment interval are based on consensus and expert opinion [6, 7] and are drafted by Ministries of Health, cancer or Medical Societies. Recommendations take the possible distress of the patient, caused by a long interval, into account. However, beside timeliness [84], interpersonal skills of the treating physician and coordination of care have a large influence on the patients’ satisfaction with waiting times [85]. This study found that a universal recommendation for the treatment interval is not available. Guidelines differ between countries, and some countries remarkably have more than one guideline, containing distinct recommendations. The recommended time to treatment ranges from two to seven weeks from decision to treat and pathological confirmation, respectively.

Ideally, the recommended lengths of the treatment interval are feasible in practice, especially considering the potential consequences when timelines do not comply with those recommendations [4, 5]. However, the reported success rates of 21–80% suggest that guidelines are not in line with practice. When these recommendations are considered indispensable, at least a uniform and feasible guideline should exist, leaving room for the professionals to deviate from this guideline. To our knowledge, there is no global initiative to draft such a uniform guideline.

Several limitations apply to the current study. Since CRC and waiting time were the focus in the search string, papers containing information on the CRC treatment interval may be missed when this was not the main subject of the paper or were included in the key words but rather mentioned as a detail. However, due to the systematic conduct including a thorough search of the bibliographies, the amount of missed records is expected to be minimal. Preferably, only papers reporting on the interval to primary treatment for elective CRC cases were included. Since the reporting on this subject is heterogenic and sometimes incomplete, this was not possible. The systematic approach of data extraction and reporting as described in the methods section diminished variety in the results. Because of the language restriction applied to this study, we conducted a survey to collect information from other countries to complement the overview. Another limitation is the retrospective nature of most of included papers assessing the association between CRC treatment interval length and outcome. However, a randomized design could be deemed unethical. This is therefore the highest level of evidence available. Finally, due to heterogeneity of studies, stratification of patients by tumor stage or location was not possible, which assumably affects outcome.

The strength of the current paper is the complete evaluation of the CRC treatment interval. Previously published systematic reviews did study the association between length of the treatment interval, and outcome, however, was not corrected for heterogeneity in the use of recommendations and definitions regarding the start of the treatment interval. Furthermore, this paper displays the recommendations of nearly 30 countries worldwide.

We focussed on the treatment interval for CRC. CRC develops slowly over time and may take up to 10–15 years before it is diagnosed [86, 87]. Furthermore, 70% of total delay until treatment is determined by the period prior to diagnosis [28, 77, 88,89,90,91]. Based on these findings, one can assume that extending time to treatment (with a reasonable amount of time) will not harm the patient. Several authors state that time frames should be flexible in order to improve a patients’ functional capacity without detrimental effects on outcome [6, 18, 36, 71, 92]. Preoperative optimization can be achieved with a multimodal prehabilitation program to enable a patient to recover faster and better, with less complications and perhaps with an improved disease-free survival [11, 12]. In other words, delaying surgery when preoperative optimization is indicated rather than nationally applied treatment goals could benefit the patient [93].

Distinct from the previously suggested start of the treatment interval, namely pathological confirmation, prehabilitation could already start earlier in the cancer care pathway. Endoscopists are capable of determining (pre)malignant lesions that need a full work-up with approximately 90% accuracy [86]. This time point often initiates the oncological care pathway including work-up. Endoscopists should be able to initiate steps toward treatment and initiate prehabilitation after date of endoscopy. In order to maximize the time available for prehabilitation, work-up until diagnosis should be arranged effectively. The amount of time possibly gained by shortening the period for work-up can be used for prehabilitation without delaying time to treatment further. Some papers even suggest to consider prehabilitation as the start of initial treatment in CRC care and as an addition to anticancer therapy regimen [7, 10].

Finally, in the current study CRC is considered as a single tumor entity. Rectal cancer surgery is often preceded by neoadjuvant treatment, and surgery is generally more radical. The differences in cancer care pathways should be taken into account when implementing a prehabilitation program.

We conclude that there is no uniform definition of the CRC treatment interval. There is no decisive evidence for an association between length of the treatment interval and outcome in CRC. Justification to consider this as a quality measure and penalize institutes not meeting this criterion is therefore questionable. Furthermore, recommendations for CRC treatment interval length included in guidelines vary widely worldwide. Meanwhile, flexibility in the length of the CRC treatment interval enables professionals to implement prehabilitation in order to improve preoperative functional capacity and outcome.

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68(6):394–424

Collins I, Naidoo J, Rowley S, Reynolds JV, Kennedy MJ (2009) Waiting times for access, diagnosis and treatment in a cancer centre. Ir Med J 102(9):279–282

Roland CL, Schwarz RE, Tong L et al (2013) Is timing to delivery of treatment a reliable measure of quality of care for patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma? Surgery 154(3):421–428

Leong KJ, Chapman MAS (2017) Current data about the benefit of prehabilitation for colorectal cancer patients undergoing surgery are not sufficient to alter the NHS cancer waiting targets. Colorectal Dis 19(6):522–524

Trickett JP, Donaldson DR, Bearn PE, Scott HJ, Hassall AC (2004) A study on the routes of referral for patients with colorectal cancer and its affect on the time to surgery and pathological stage. Colorectal Dis 6(6):428–431

Flemming JA, Nanji S, Wei X, Webber C, Groome P, Booth CM (2017) Association between the time to surgery and survival among patients with colon cancer: a population-based study. Eur J Surg Oncol 43(8):1447–1455

Hangaard Hansen C, Gogenur M, Tvilling Madsen M, Gogenur I (2018) The effect of time from diagnosis to surgery on oncological outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for colon cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol 44(10):1479–1485

Minnella EM, Bousquet-Dion G, Awasthi R, Scheede-Bergdahl C, Carli F (2017) Multimodal prehabilitation improves functional capacity before and after colorectal surgery for cancer: a five-year research experience. Acta Oncol 56(2):295–300

Heger P, Probst P, Wiskemann J, Steindorf K, Diener MK, Mihaljevic AL (2019) A systematic review and meta-analysis of physical exercise prehabilitation in major abdominal surgery (PROSPERO 2017 CRD42017080366). J Gastrointest Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-019-04287-w

West MA, Astin R, Moyses HE et al (2019) Exercise prehabilitation may lead to augmented tumor regression following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Acta Oncol 58(5):588–595

Barberan-Garcia A, Ubre M, Roca J et al (2018) Personalised prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery: a randomized blinded controlled trial. Ann Surg 267(1):50–56

Trepanier M, Minnella EM, Paradis T et al (2019) Improved disease-free survival after prehabilitation for colorectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003465

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 62(10):1

European network of cancer registries—call for data. https://www.encr.eu/sites/default/files/pdf/2015_ENCR_JRC_Call_for_Data_Version_1_1.pdf. Updated 2015. Accessed 19 Sep 2019

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097

Roder D, Karapetis CS, Olver I et al (2019) Time from diagnosis to treatment of colorectal cancer in a south australian clinical registry cohort: How it varies and relates to survival. BMJ Open 9(9):e031421-031421

National definitions for elective surgery urgency categories—Australia. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/hospitals/national-definitions-for-elective-surgery-urgency/contents/table-of-contents. Updated 2013. Accessed 23 July 2020

Wanis KN, Patel SVB, Brackstone M (2017) Do moderate surgical treatment delays influence survival in colon cancer? Dis Colon Rectum 60(12):1241–1249

Cancer care Ontario expert panel report. https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/content/target-wait-times-cancer-surgery-ontario, http://waittimes.alberta.ca/AWTRInfoPage.jsp?pageID=32. Updated 2006. Accessed 18 Sep 2019

Bardell T, Belliveau P, Kong W, Mackillop WJ (2006) Waiting times for cancer surgery in ontario: 1984–2000. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 18(5):401–409

Simunovic M, Gagliardi A, McCready D, Coates A, Levine M, DePetrillo D (2001) A snapshot of waiting times for cancer surgery provided by surgeons affiliated with regional cancer centres in ontario. CMAJ 165(4):421–425

Simunovic M, Rempel E, Theriault ME et al (2009) Influence of delays to nonemergent colon cancer surgery on operative mortality, disease-specific survival and overall survival. Can J Surg 52(4):E79–E86

Helewa RM, Turner D, Park J et al (2013) Longer waiting times for patients undergoing colorectal cancer surgery are not associated with decreased survival. J Surg Oncol 108(6):378–384

Wait time alliance—Canada. http://www.waittimealliance.ca/benchmarks/general-surgery/. Accessed 19 Sept 2019

Rectal cancer surgery standards—Canada. https://s22457.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Rectal-Cancer-Surgery-Standards-EN.pdf. Updated 2019. Accessed 19 Sept 2019

Johnston GM, MacGarvie VL, Elliott D, Dewar RA, MacIntyre MM, Nolan MC (2004) Radiotherapy wait times for patients with a diagnosis of invasive cancer, 1992–2000. Clin Invest Med 27(3):142–156

Korsgaard M, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT, Laurberg S (2006) Delay of treatment is associated with advanced stage of rectal cancer but not of colon cancer. Cancer Detect Prev 30(4):341–346

Korsgaard M, Pedersen L, Laurberg S (2008) Delay of diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer–a population-based danish study. Cancer Detect Prev 32(1):45–51

Estonian cancer treatment quality assurance plan. https://www.sm.ee/sites/default/files/content-editors/eesmargid_ja_tegevused/Tervis/Tervislik_eluviis/eesti_vahiravi_kvaliteedi_tagamise_nouded.pdf. Updated 2011. Accessed 11 Aug 2020

Valente R, Testi A, Tanfani E et al (2009) A model to prioritize access to elective surgery on the basis of clinical urgency and waiting time. BMC Health Serv Res 9:1–1

Abu-Helalah AM, Alshraideh HA, Al-Hanaqtah M, Da’na M, Al-Omari A, Mubaidin R (2016) Delay in presentation, diagnosis, and treatment for breast cancer patients in jordan. Breast J 22(2):213–217

Yun YH, Kim YA, Min YH et al (2012) The influence of hospital volume and surgical treatment delay on long-term survival after cancer surgery. Ann Oncol 23(10):2731–2737

Lino-Silva LS, Guzmán-López JC, Zepeda-Najar C, Salcedo-Hernández RA, Meneses-García A (2019) Overall survival of patients with colon cancer and a prolonged time to surgery. J Surg Oncol 119(4):503–509

Multidisciplinary standardization oncological care in the Netherlands. https://www.soncos.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/43SONCOS-normeringsrapport-versie-5.pdf. Updated 2017. Accessed 13 March 2018

Gort M, Otter R, Plukker JT, Broekhuis M, Klazinga NS (2010) Actionable indicators for short and long term outcomes in rectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 46(10):1808–1814

Strous MTA, Janssen-Heijnen MLG, Vogelaar FJ (2019) Impact of therapeutic delay in colorectal cancer on overall survival and cancer recurrence: Is there a safe timeframe for prehabilitation? Eur J Surg Oncol 45(12):2295–2301

van der Geest LG, Elferink MA, Steup WH et al (2014) Guidelines-based diagnostic process does increase hospital delay in a cohort of colorectal cancer patients: A population-based study. Eur J Cancer Prev 23(5):344–352

Treeknorm—Netherlands. https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-25170-31.html#IDAPMDFB. Updated 2003. Accessed 1 Oct 2019

van Steenbergen LN, Lemmens VE, Rutten HJ, Martijn H, Coebergh JW (2010) Was there shortening of the interval between diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer in southern netherlands between 2005 and 2008? World J Surg 34(5):1071–1079. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0480-x

Recommendations waiting time standards for cancer care of Dutch Cancer Society. https://www.oncoline.nl/uploaded/docs/Draaiboek/Normatieve%20wachttijden.pdf. Updated 2006. Accessed 26 Sept 2019

Tiong J, Gray A, Jackson C, Thompson-Fawcett M, Schultz M (2017) Audit of the association between length of time spent on diagnostic work-up and tumour stage in patients with symptomatic colon cancer. ANZ J Surg 87(3):138–142

National cancer program—New Zealand. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/national-cancer-programme/cancer-initiatives/faster-cancer-treatment#:~:text=Faster%20cancer%20treatment%20indicators%20were,a%20high%20suspicion%20of%20cancer. Updated 2018. Accessed 13 Aug 2020

National cancer strategy 2013–2017 – Norway https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/07cd14ff763444a3997de1570b85fad1/i-1158_together-against_cancer_web.pdf. Accessed 8 July 2020

Nilssen Y, Brustugun OT, Tandberg Eriksen M et al (2019) Decreasing waiting time for treatment before and during implementation of cancer patient pathways in norway. Cancer Epidemiol 61:59–69

National colorectal cancer program—Norway. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/kreft-i-tykktarm-og-endetarm-handlingsprogram/IS%202849%20Nasjonalt%20handlingsprogram%20kreft%20i%20tykktarm%20og%20endetarm.pdf/_/attachment/inline/4a5fa48e-8d76-4618-98b3-43af5a85b76e:4c4a29f71e7a68ff93a19dd82848f36a49abff81/IS-2849%20Nasjonalt%20handlingsprogram%20kreft%20i%20tykktarm%20og%20endetarm.pdf. Updated 2019. Accessed 17 Aug 2020

Osowiecka K, Rucinska M, Nowakowski JJ, Nawrocki S (2018) How long are cancer patients waiting for oncological therapy in poland? Int J Environ Res Public Health 15:4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040577

Zarcos-Pedrinaci I, Fernandez-Lopez A, Tellez T et al (2017) Factors that influence treatment delay in patients with colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 8(22):36728–36742

Guzman Laura KP, Bolibar Ribas I, Alepuz MT, Gonzalez D, Martin M (2011) Impact on patient care time and tumor stage of a program for fast diagnostic and treatment of colorectal cancer. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 103(1):13–19

Prades J, Espinas JA, Font R, Argimon JM, Borras JM (2011) Implementing a cancer fast-track programme between primary and specialised care in catalonia (spain): a mixed methods study. Br J Cancer 105(6):753–759

Standardized program for colorectal cancer—Sweden. https://kunskapsbanken.cancercentrum.se/diagnoser/tjock-och-andtarmscancer/vardforlopp/#-Fldesschema-fr-vrdfrloppet). Accessed 27 Feb 2020

Raje D, La Touche S, Mukhtar H, Oshowo A, Ingham CC (2006) Changing trends in the management of colorectal cancers and its impact on cancer waiting times. Colorectal Dis 8(2):140–144

Di Girolamo C, Walters S, Gildea C, Benitez Majano S, Rachet B, Morris M (2018) Can we assess cancer waiting time targets with cancer survival? A population-based study of individually linked data from the national cancer waiting times monitoring dataset in england, 2009–2013. PLoS ONE 13(8):e0201288

National health service cancer progamme 2000—United Kingdom. https://www.thh.nhs.uk/documents/_Departments/Cancer/NHSCancerPlan.pdf. Accessed 1 Oct 2019

Duff SE, Wood C, McCredie V, Levine E, Saunders MP, O’Dwyer ST (2004) Waiting times for treatment of rectal cancer in north west england. J R Soc Med 97(3):117–118

Robertson R, Campbell NC, Smith S et al (2004) Factors influencing time from presentation to treatment of colorectal and breast cancer in urban and rural areas. Br J Cancer 90(8):1479–1485

Chohan DP, Goodwin K, Wilkinson S, Miller R, Hall NR (2005) How has the “two-week wait” rule affected the presentation of colorectal cancer? Colorectal Dis 7(5):450–453

Maruthachalam K, Stoker E, Chaudhri S, Noblett S, Horgan AF (2005) Evolution of the two-week rule pathway–direct access colonoscopy vs outpatient appointments: one year’s experience and patient satisfaction survey. Colorectal Dis 7(5):480–485

Robinson D, Massey T, Davies E, Jack RH, Sehgal A, Moller H (2005) Waiting times for radiotherapy: variation over time and between cancer networks in southeast england. Br J Cancer 92(7):1201–1208

Currie AC, Evans J, Smith NJ, Brown G, Abulafi AM, Swift RI (2012) The impact of the two-week wait referral pathway on rectal cancer survival. Colorectal Dis 14(7):848–853

Redaniel MT, Martin RM, Blazeby JM, Wade J, Jeffreys M (2014) The association of time between diagnosis and major resection with poorer colorectal cancer survival: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer 14:642–642

Aslam MI, Chaudhri S, Singh B, Jameson JS (2017) The “two-week wait” referral pathway is not associated with improved survival for patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Surg 43:181–185

Etzioni DA (2011) Timeliness of care. Semin Colon Rectal Surg 22:222–225

Eaglehouse YL, Georg MW, Shriver CD, Zhu K (2020) Racial comparisons in timeliness of colon cancer treatment in an equal-access health system. J Natl Cancer Inst 112(4):410–417

Law CW, Roslani AC, Ng LL (2009) Treatment delay in rectal cancer. Med J Malaysia 64(2):163–165

Terhaarsive Droste JS, Oort FA, van der Hulst RW et al (2010) Does delay in diagnosing colorectal cancer in symptomatic patients affect tumor stage and survival? A population-based observational study. BMC Cancer 10:332–332

Van Hout AM, de Wit NJ, Rutten FH, Peeters PH (2011) Determinants of patient’s and doctor’s delay in diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 23(11):1056–1063

Deng SX, An W, Gao J et al (2012) Factors influencing diagnosis of colorectal cancer: a hospital-based survey in china. J Dig Dis 13(10):517–524

Pruitt SL, Harzke AJ, Davidson NO, Schootman M (2013) Do diagnostic and treatment delays for colorectal cancer increase risk of death? Cancer Causes Control 24(5):961–977

Amri R, Bordeianou LG, Sylla P, Berger DL (2014) Treatment delay in surgically-treated colon cancer: Does it affect outcomes? Ann Surg Oncol 21(12):3909–3916

Curtis NJ, West MA, Salib E et al (2018) Time from colorectal cancer diagnosis to laparoscopic curative surgery-is there a safe window for prehabilitation? Int J Colorectal Dis 33(7):979–983

Weller D, Menon U, Zalounina Falborg A et al (2018) Diagnostic routes and time intervals for patients with colorectal cancer in 10 international jurisdictions; findings from a cross-sectional study from the international cancer benchmarking partnership (ICBP). BMJ Open 8(11):e023870-023870

Shin DW, Cho J, Kim SY et al (2013) Delay to curative surgery greater than 12 weeks is associated with increased mortality in patients with colorectal and breast cancer but not lung or thyroid cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 20(8):2468–2476

Bagaria SP, Heckman MG, Diehl NN, Parker A, Wasif N (2019) Delay to colectomy and survival for patients diagnosed with colon cancer. J Invest Surg 32(4):350–357

Khorana AA, Tullio K, Elson P et al (2019) Time to initial cancer treatment in the united states and association with survival over time: an observational study. PLoS ONE 14(3):e0213209

Lee YH, Kung PT, Wang YH, Kuo WY, Kao SL, Tsai WC (2019) Effect of length of time from diagnosis to treatment on colorectal cancer survival: a population-based study. PLoS ONE 14(1):e0210465

McConnell YJ, Inglis K, Porter GA (2010) Timely access and quality of care in colorectal cancer: Are they related? Int J Qual Health Care 22(3):219–228

Kaltenmeier C, Shen C, Medich DS et al (2019) Time to surgery and colon cancer survival in the united states. Ann Surg. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003745

Kucejko RJ, Holleran TJ, Stein DE, Poggio JL (2020) How soon should patients with colon cancer undergo definitive resection? Dis Colon Rectum 63(2):172–182

Grunfeld E, Watters JM, Urquhart R et al (2009) A prospective study of peri-diagnostic and surgical wait times for patients with presumptive colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer. Br J Cancer 100(1):56–62

Weller D, Vedsted P, Rubin G et al (2012) The aarhus statement: Improving design and reporting of studies on early cancer diagnosis. Br J Cancer 106(7):1262–1267

Macia F, Pumarega J, Gallen M, Porta M (2013) Time from (clinical or certainty) diagnosis to treatment onset in cancer patients: The choice of diagnostic date strongly influences differences in therapeutic delay by tumor site and stage. J Clin Epidemiol 66(8):928–939

Neal RD, Tharmanathan P, France B et al (2015) Is increased time to diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic cancer associated with poorer outcomes? systematic review. Br J Cancer 112(Suppl 1):92

Malmstrom M, Rasmussen BH, Bernhardson BM et al (2018) It is important that the process goes quickly, isn’t it?" A qualitative multi-country study of colorectal or lung cancer patients’ narratives of the timeliness of diagnosis and quality of care. Eur J Oncol Nurs 34:82–88

Mathews M, Ryan D, Bulman D (2015) What does satisfaction with wait times mean to cancer patients? BMC Cancer 15:1017-z

Moore JS, Aulet TH (2017) Colorectal cancer screening. Surg Clin North Am 97(3):487–502

Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM, Wallace MB (2019) Colorectal cancer. Lancet 394(10207):1467–1480

Langenbach MR, Schmidt J, Neumann J, Zirngibl H (2003) Delay in treatment of colorectal cancer: multifactorial problem. World J Surg 27(3):304–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-002-6678-9

Flashman K, O’Leary DP, Senapati A, Thompson MR (2004) The department of health’s “two week standard” for bowel cancer: Is it working? Gut 53(3):387–391

Langenbach MR, Sauerland S, Krobel KW, Zirngibl H (2010) Why so late?!–delay in treatment of colorectal cancer is socially determined. Langenbecks Arch Surg 395(8):1017–1024

Thompson MR, Heath I, Swarbrick ET, Wood LF, Ellis BG (2011) Earlier diagnosis and treatment of symptomatic bowel cancer: Can it be achieved and how much will it improve survival? Colorectal Dis 13(1):6–16

Dua RS, Brown VS, Loukogeorgakis SP, Kallis G, Meleagros L (2009) The two-week rule in colorectal cancer: Can it deliver its promise? Int J Surg 7(6):521–525

Sothisrihari SR, Wright C, Hammond T (2017) Should preoperative optimization of colorectal cancer patients supersede the demands of the 62-day pathway? Colorectal Dis 19(7):617–620

Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P et al (2013) Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med 369(12):1095–1105

Acknowledgements

The authors thank E. Delvaux (Máxima MC) for her contribution in the literature search and S.J.P. Jansen for his contribution in the development of the survey. We thank the following colorectal surgeons for their contribution to the current study by completing the survey: A. Ponson, Dr. Horacio Oduber Hospital (Aruba); Assoc. Prof. T. Sammour, Royal Adelaide Hospital (Australia); Prof. A.M. Wolthuis, University Hospitals Leuven (Belgium); M. Valadão, Instituto Nacional de Câncer (Brazil); Z. Wu, Peking University Cancer Hospital (China); P. Vlček, St. Ann's University Hospital (Czech Republic); Prof. I. Gögenur, Zealand University Hospital (Denmark); O. Tammik, Tartu University Clinic (Estonia); Prof. E. Cotte, Lyon-Sud Hospital (France); Prof. E. Xynos, Creta Interclinic Hospital (Greece); D. Toth, Academic County Hospital (Hungary); Prof. D.C. Winter, St. Vincent's University Hospital (Ireland); Prof. L. Boni, Surgery Policlinico of Milan (Italy); H. Ota, Ikeda City Hospital (Japan); Assoc. Prof. G. O’Grady, Auckland City Hospital (New Zealand); R. Gaupset, Akershus University Hospital (Norway); I. Negoi, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy Bucharest (Romania); Assoc. Prof. L. Marko, Roosevelt Hospital (Slovak Republic); M. Frasson, University Hospital La Fe (Spain); Assoc. Prof. P.J. Nilsson, Karolinska University Hospital (Sweden); Prof. D. Hahnloser, University Hospital Lausanne (Switzerland); and Prof. T.A. Rockall, Royal Surrey County Hospital NHS Trust (UK). Finally, we would like to thank the peer reviewers for their feedback and recommendations on this manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CM, LJ and GS made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study. CM performed the literature and web search. CM, LJ and GS screened and selected papers and extracted data from the included studies. CM, LJ and GS designed the survey. CM and GS sent the survey and extracted data. CM and GS conducted the web search. All authors contributed to data interpretation. CM, LJ, RR and GS primarily drafted the manuscript, and all authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Molenaar, C.J.L., Janssen, L., van der Peet, D.L. et al. Conflicting Guidelines: A Systematic Review on the Proper Interval for Colorectal Cancer Treatment. World J Surg 45, 2235–2250 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-021-06075-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-021-06075-7