Abstract

Background

Recent NICE guidelines recommend open surgical approaches for the treatment of primary unilateral inguinal hernias. However, many surgeons perform a laparoscopic approach based on the advantages of less post-operative pain and faster recovery. Our aim was to examine current evidence comparing transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) laparoscopic repair and open surgical repair for primary inguinal hernias.

Methods

A systematic search of six electronic databases was conducted for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing TAPP and open repair for primary unilateral inguinal hernia. A random-effects model was used to combine the data.

Results

A total of 13 RCTs were identified, with 1310 patients receiving TAPP repair and 1331 patients receiving open repair. There was no significant difference between the two groups for rates of haematoma (RR 0.92; 95% CI 0.49–1.71; P = 0.78), seroma (RR 1.90; 95% CI 0.87–4.14; P = 0.10), urinary retention (RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.36–2.76; P = 0.99), infection (RR 0.61; 95% CI 0.29–1.28; P = 0.19), and hernia recurrence (RR 0.67; 95% CI 0.42–1.07; P = 0.10). TAPP repair had a significantly lower rate of paraesthesia (RR 0.20; 95% CI 0.08–0.50; P = 0.0005), shorter bed stay (2.4 ± 1.4 vs 3.1 ± 1.6 days, P = 0.0006), and shorter return to normal activities (9.5 ± 7.9 vs 17.3 ± 8.4 days, P < 0.00001).

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrated that TAPP repair did not have higher rate of morbidity or hernia recurrence and is an equivalent approach to open repair, with the advantages of faster recovery and reduced paraesthesia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inguinal hernia repair is a common procedure performed in general surgery, with an annual rate of 28 per 100,000 of the population in the USA [1]. Inguinal hernias account for 75% of abdominal wall hernias, in which there is a lifetime risk of 27% for men and 3% for women [2]. Operative techniques have continuously evolved over the past six decades to provide optimal management of inguinal hernias. Recent U. K. national guidelines recommended that both laparoscopic and open repair are equivalent treatment options for primary unilateral inguinal hernias [3].

The most frequently used tension-free open techniques include Lichtenstein, Shouldice, and Bassini repairs [4]. The Lichtenstein repair involves the implantation of a mesh prosthesis ventral to the transversalis fascia [5]. On the other hand, both Shouldice and Bassini repairs are non-mesh techniques that use a continuous non-absorbable suture to reconstruct the muscle layers in order to strengthen the inguinal floor [6]. A common minimally invasive approach is the transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) technique, which places a mesh prosthesis into the pre-peritoneal space dorsal to the transversalis fascia [7]. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair is stated to have short-term advantages of shorter convalescence and less chronic post-operative pain over open repair [8]. Another laparoscopic approach is the totally extra-peritoneal (TEP) technique, which creates a pre-peritoneal space without entering the abdominal cavity and places the mesh in the same space as the TAPP technique [9].

Indeed, many surgeons now perform a laparoscopic repair of some type for all primary unilateral inguinal hernias, in which there is widespread patient expectation that the procedure should be performed laparoscopically [10]. Thus, an evaluation of current evidence that focuses on the short-term efficacy and safety and the long-term outcomes comparing TAPP and open repair is warranted to determine the most appropriate approach for the treatment of primary, unilateral inguinal hernias. To assess this, we performed a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared patients receiving TAPP versus open repair. Our aim was to assess the early outcomes of morbidity and recovery and long-term outcomes of hernia recurrence, and other surgery-related morbidities.

Methods

Search strategy

The present meta-analysis was conducted according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11]. Electronic searches were performed using Ovid Medline, PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCTR), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), American College of Physician (ACP) Journal Club, and Database of Abstracts of Review of Effectiveness (DARE) from their date of inception to January 2017. To achieve maximum sensitivity of the search strategy and identify all studies, we used the following keywords or MeSH terms: “transabdominal pre-peritoneal”, “open inguinal hernia repair”, “Lichtenstein”, “Shouldice”, “Bassini”, and “primary inguinal hernia”. The reference lists of all retrieved articles were reviewed for further identification of potentially relevant studies using the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Selection criteria

Eligible studies for the present meta-analysis included RCTs that compared patients receiving TAPP versus open repair. Studies that did not contain a comparative group report primary unilateral inguinal hernias, include hernia recurrence rate, or include post-operative complications as endpoints were excluded. When institutions published duplicate studies with accumulating numbers of patients or increased lengths of follow-up, only the most complete reports were included for quantitative assessment. All publications were limited to those that involved human subjects. Abstracts, case reports, conference presentations, editorials, reviews, and expert opinions were excluded.

Data extraction and critical appraisal

All data were extracted from article texts, tables, and figures. Two investigators (JJW and JAW) independently reviewed each retrieved article. The risk of bias assessment in RCTs was performed based on methodological items proposed by the Cochrane Collaboration (Supplementary Table 1) [12]. These include adequacy of random sequence generation, blinding, incomplete reporting of outcome data, selective presentation of outcomes, consistency of description of sample-size calculation, and disclosure of funding sources. Discrepancies between the two investigators were resolved by discussion and consensus with the senior author (MRC).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was hernia recurrence. The secondary outcomes were haematoma, seroma, urinary retention, infection, post-operative pain, paraesthesia, and chronic pain. All endpoints were assessed at the longest follow-up available and according to the definitions reported in the original study protocols.

Statistical analysis

Clinical outcomes were analysed using a standard and cumulative meta-analysis, with risk ratio (RR) used as a summary statistic to compare rates of post-operative complication between TAPP and open repair groups. In the present meta-analysis, fixed-effects and random-effects models were both tested. The fixed-effects model assumed that treatment effect in each study was the same, whereas the random-effects model assumed that there were variations between the studies. The Chi-square test was used to assess heterogeneity between the studies. The I2 statistic was used to estimate the percentage of total variation across the studies owing to heterogeneity rather than chance, with values greater than 50% considered as substantial heterogeneity [12]. All P values were two sided. The statistical analysis was performed with RevMan Version 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen).

Results

Literature search

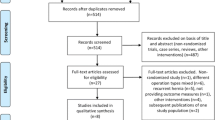

A total of 1278 studies were identified through six electronic database searches (Fig. 1). After exclusion of duplicate or irrelevant references, 168 potentially relevant articles were retrieved. After application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 13 relevant studies were included in the present meta-analysis. A total of 2641 patients were included for analysis, with 1310 receiving TAPP repair and 1331 receiving open repair. All studies reported rates of post-operative complications. Table 1 summarises the study characteristics of the included trials.

Patient and procedural characteristics

Table 2 outlines the baseline characteristics of the included trials. Overall, the age (48.3 ± 11.8 vs 48.8 ± 11.4 years; P = 0.98), male gender (96.8 vs 96.0%; P = 0.02), indirect inguinal hernias (75.5 vs 61.8%; P = 0.16), and mixed inguinal hernias (9.5 vs 7.9%; P = 0.4) were similar between the two groups. However, the proportion of direct inguinal hernias was significantly higher in the open repair group (23.2 vs 32.7%; P = 0.005). There was a significantly longer operating time for patients receiving TAPP repair than those receiving open repair (64.5 ± 15.1 vs 50.3 ± 15.6 min; P = 0.01).

Patient recovery

There was a significantly shorter hospital stay for patients receiving TAPP repair than those receiving open repair (2.4 ± 1.4 vs 3.1 ± 1.6 days; P = 0.0006). There was a significantly faster return to normal activities for patients receiving TAPP repair than those receiving open repair (9.5 ± 7.9 vs 17.3 ± 8.4 days; P < 0.0001). Likewise, there was a significantly faster return to work for patients receiving TAPP than those receiving open repair (16 ± 8 vs 26 ± 11 days; P < 0.00001).

Early morbidity

Seven trials [13,14,15,16,17,18,19] reported details of haematoma, with follow-up ranging from 1.5 to 32 months. In a comparison of 499 TAPP repair patients and 520 open repair patients, there was no significant difference for the rate of haematoma (3.4 vs 4.2%; RR 0.92; 95% CI 0.49–1.71; P = 0.78; I2 = 0%). Five trials [13, 17,18,19,20] reported details of seroma, with follow-up ranging from 1.5 to 32 months. In a comparison of 370 TAPP patients and 387 open repair patients, there was no significant difference for the rate of seroma (7.8 vs 3.9%; RR 1.90; 95% CI 0.87–4.14; P = 0.10; I2 = 25%). Four trials [15, 19, 21, 22] reported details of urinary retention, with follow-up ranging from 1.5 to 25 months. In a comparison of 268 TAPP patients and 280 open repair patients, there was no significant difference for the rate of urinary retention (4.9 vs 5.4%; RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.36–2.76; P = 0.99; I2 = 34%). Eight trials [13,14,15,16, 18, 19, 21, 23] reported details of infection, with follow-up ranging from 1.5 to 32 months. In a comparison of 579 TAPP patients and 591 open repair patients, there was no significant difference for the rate of infection (2.1 vs 3.4%; RR 0.61; 95% CI 0.29–1.28; P = 0.19; I2 = 0%).

Although there was no significant difference between the two groups for specific complications, there was significantly less post-operative pain at 24 h in the TAPP repair group (3.5 ± 0.8 vs 6.6 ± 0.7; P = 0.007). This was reported in two trials [14, 19] where post-operative pain was assessed by the visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 to 10.

Late outcomes

All trials reported details of hernia recurrence, with follow-up ranging from 1.5 to 70 months. In a comparison of 1336 TAPP patients and 1335 open repair patients, there was no significant difference for the rate of hernia recurrence (3.8 vs 5.5%; RR 0.67; 95% CI 0.42–1.97; P = 0.10; I2 = 18%; Fig. 2). Subgroup analysis found no significant difference between TAPP and open mesh repair for the rate of hernia recurrence (2.1 vs 4.8%; RR 0.52; 95% CI 0.22–1.24; P = 0.14; I2 = 0%). Similarly, there was no significant difference between TAPP and open non-mesh repair for the rate of hernia recurrence (4.4 vs 5.8%; RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.37–1.55; P = 0.44; I2 = 44%).

Four studies [18, 20, 21, 23] reported details of paraesthesia, with follow-up ranging from 16 to 52 months. In a comparison of 339 TAPP patients and 323 open repair patients, there was a significantly lower rate of paraesthesia (5.3 vs 30.0%; RR 0.20; 95% CI 0.08–0.50; P = 0.0005; I2 = 67%; Fig. 3). Two trials [13, 15] reported details of visceral injury and demonstrated no significant difference between TAPP and open repairs (0.4 vs 0.0%; RR 3.30; 95% CI 0.14–80.05; P = 0.46). Only one trial [17] reported details of vascular injury, and there was no difference between TAPP and open repairs. Only one trial [13] reported details of chronic pain, and there was no difference between TAPP and open repairs.

Discussion

In the present meta-analysis of RCTs, we found no significant difference for the rate of hernia recurrence in patients receiving TAPP repair than those receiving open repair for primary unilateral inguinal hernias. Although there was no difference in the incidence of chronic post-operative pain, there was a significantly lower rate of paraesthesia in the TAPP repair group. Comparison of early outcomes showed that there were similar rates of other surgery-related morbidities, such as haematoma, seroma, urinary retention, and infection, between the two groups. The sole advantage of open surgery was its significantly shorter operating time. TAPP repair had significantly less post-operative pain, shorter hospital stay, return to normal activities, and return to work.

Our findings showed similar recurrence rates, which have previously been reported in a meta-analysis [24] of 7161 patients receiving TAPP versus open repair. In the same study, TAPP had reduced post-operative pain and paraesthesia, and faster return to normal activities. In our meta-analysis, one of the included trials [25] showed a recurrence rate of 6.6% after 5 years in the TAPP repair group, which was possibly higher than expected. The investigators suggested that this may be a consequence of the use of a small mesh (7 × 12 cm), which was recommended when the study was initiated. Polypropylene mesh shrinks up to 40%, emphasising the need for a large mesh to achieve good coverage of the inguinal area [26].

Early concerns that laparoscopic repair would be associated with a higher recurrence rate are clearly not supported by our results. Furthermore, our findings confirmed other studies that TAPP had significant advantages of a shorter hospital stay, earlier return to normal activities, and earlier return to work [27, 28]. Although the operating time for open surgery is on average 14 min faster, this apparent advantage is in no way outweighed by the significant improvements noted in the recovery time.

TEP has been widely accepted as an alternative laparoscopic technique for primary inguinal hernia repair. However, when considering a comparison between TEP and open repair, examination of the literature revealed a paucity of RCTs comparing TEP with open surgery. Hence, the study comparing TAPP with open surgery was performed instead. It is highly likely that the advantages seen in primary repair of unilateral inguinal hernia with TAPP compared to open surgery would also exist for TEP compared to open surgery. A meta-analysis [29] of 1047 patients reported that TEP, as a modified and more complex laparoscopic procedure, did not lead to a significant difference in early or late clinical outcomes compared with TAPP. However, surgeons may encounter technical difficulties when performing TEP owing to unfamiliar pelvic anatomy and limited working space. Both of these factors translate to a steeper learning curve for inexperienced surgeons to become proficient at TEP [30]. The choice of laparoscopic approach would be made according to the clinical characteristics of patients and experience of surgeons.

Our results demonstrated similar rates of haematoma, seroma, urinary retention, and infection between TAPP and open repair. Likewise, a retrospective study [31] showed that the rates of these post-operative complications in patients with laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair were comparable to those with open repair.

Although the present meta-analysis revealed that TAPP repair was associated with a lower rate of paraesthesia than open repair, many surgeons are now performing prophylactic ilioinguinal neurectomy during inguinal hernia repair to avoid nerve entrapment. A RCT [32] showed that prophylactic excision of the ilioinguinal nerve during Lichtenstein repair significantly reduced the incidence of chronic groin pain and numbness without added morbidities. The investigators recommended that prophylactic ilioinguinal neurectomy should be performed as a routine surgical step during an open operation. The wide adoption of this practice is the likely reason for the increase in paraesthesia noted in the present meta-analysis. However, the occurrence of paraesthesia, which was higher than expected, is not necessarily a significant problem. The incidence of chronic pain is a more significant clinical problem for which there was no significant difference in the present meta-analysis.

Laparoscopic repairs have been associated with higher rates of visceral and vascular injuries compared to open repairs [33]. In the present study, there was a low incidence of these injuries in the TAPP group and none in the open group. Due to the low incidence of these injuries, there was no significant difference between the groups. Nonetheless, the potential for serious and potentially devastating complications needs to be considered when comparing the two techniques.

Our meta-analysis reduced the risk of bias by combining data from RCTs only. A larger patient cohort for each comparator arm would have been possible if data from observational studies were included. Given the cumulative evidence and absence of significant heterogeneity, the overall summary estimates for the post-operative outcomes were unlikely to change by the inclusion of observational studies using less stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria. There are limitations that should be acknowledged, and the results should be interpreted with caution. Firstly, RCTs with greater follow-up and number of patients are required to evaluate the long-term efficacy beyond 10 years of either TAPP or TEP for primary inguinal hernias. Furthermore, post-operative pain should be measured according to a standardised definition across the trials, allowing a more reliable assessment of the degree of pain after primary inguinal hernia repair. This is particularly relevant for the assessment of chronic post-operative pain. The included RCTs used open techniques that involved repairs with or without mesh. This may dilute all outcome measures in the present meta-analysis, particularly recurrence rates, morbidity, and chronic post-operative pain.

In summary, our findings demonstrated that TAPP repair is an equivalent surgical approach to open repair for the treatment of primary unilateral inguinal hernias. TAPP repair has the additional advantages of faster post-operative recovery and reduced paraesthesia.

References

Jenkins JT, O’Dwyer PJ (2008) Inguinal hernias. BMJ 336(7638):269–272

Kingsnorth A, LeBlanc K (2003) Hernias: inguinal and incisional. Lancet 362(9395):1561–1571

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016) NICE technology appraisal guidance no. 83: laparoscopic surgery for inguinal hernia repair

Anand A, Sinha PA, Kittappa K, Mulchandani MH, Debrah S, Brookstein R (2011) Review of inguinal hernia repairs by various surgical techniques in a district general hospital in the UK. Indian J Surg 73(1):13–18

Pahwa HS, Kumar A, Agarwal P, Agarwal AA (2015) Current trends in laparoscopic groin hernia repair: a review. World J Clin Cases 3(9):789–792

Amid PK (2005) Groin hernia repair: open techniques. World J Surg 29(8):1046–1051. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-7967-x

Watson A, Ziprin P, Chadwick S (2006) TAPP repair for inguinal hernia: a new composite mesh technique. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 88(7):678

Berndsen F, Arvidsson D, Enander LK, Leijonmarck CE, Wingren U, Rudberg C, Smedberg S, Wickbom G, Montgomery A (2002) Postoperative convalescence after inguinal hernia surgery: prospective randomized multicenter study of laparoscopic versus shouldice inguinal hernia repair in 1042 patients. Hernia 6(2):56–61

Carter J, Duh QY (2011) Laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernias. World J Surg 35(7):1519–1525. doi:10.1007/s00268-011-1030-x

Bhandarkar DS, Shankar M, Udaadia TE (2006) Laparoscopic surgery for inguinal hernia: current status and controversies. J Minim Access Surg 2(3):178–186

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151(4):264–269

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327(7414):557–560

Abbas AE, Abd Ellatif ME, Noaman N, Negm A, El-Morsy G, Amin M, Moatamed A (2012) Patient-perspective quality of life after laparoscopic and open hernia repair: a controlled randomized trial. Surg Endosc 26(9):2465–2470

Anadol ZA, Ersoy E, Taneri F, Tekin E (2004) Outcome and cost comparison of laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal hernia repair versus open Lichtenstein technique. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 14(3):159–163

Gong K, Zhang N, Lu Y, Zhu B, Zhang Z, Du D, Zhao X, Jiang H (2011) Comparison of the open tension-free mesh-plug, transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP), and totally extraperitoneal (TEP) laparoscopic techniques for primary unilateral inguinal hernia repair: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc 25(1):234–239

Juul P, Christensen K (1999) Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 86(3):316–319

Lawrence K, McWhinnie D, Goodwin A, Doll H, Gordon A, Gray A, Britton J, Collin J (1995) Randomised controlled trial of laparoscopic versus open repair of inguinal hernia: early results. BMJ 311(7011):981–985

Tanphiphat C, Tanprayoon T, Sangsubhan C, Chatamra K (1998) Laparoscopic vs open inguinal hernia repair. A randomized, controlled trial. Surg Endosc 12(6):846–851

Zieren J, Zieren HU, Jacobi CA, Wenger FA, Müller JM (1998) Prospective randomized study comparing laparoscopic and open tension-free inguinal hernia repair with Shouldice’s operation. Am J Surg 175(4):330–333

Wang WJ, Chen JZ, Fang Q, Lin JF, Jin PF, Li ZT (2013) Comparison of the effects of laparoscopic hernia repair and Lichtenstein tension-free hernia repair. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 23(4):301–305

Dirksen CD, Beets GL, Go PM, Geisler FE, Baeten CG, Kootstra G (1998) Bassini repair compared with laparoscopic repair for primary inguinal hernia: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Surg 164(6):439–447

Khan N, Babar TS, Ahmad M, Ahmad Z, Shah LA (2013) Outcome and cost comparison of laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal hernia repair versus open Lichtenstein technique. J Postgrad Med Inst 27(3):310–316

Butters M, Redecke J, Koninger J (2007) Long-term results of a randomized clinical trial of Shouldice, Lichtenstein and transabdominal preperitoneal hernia repair. Br J Surg 94(5):562–565

O’Reilly EA, Burke JP, O’Connell PR (2012) A meta-analysis of surgical morbidity and recurrence after laparoscopic and open repair of primary unilateral inguinal hernia. Ann Surg 255(5):846–853

Arvidson D, Berndsen FH, Larsson LG, Leijonmarck CE, Rimbäck G, Rudberg C, Smedberg S, Spangen L, Montgomery A (2005) Randomized clinical trial comparing 5-year recurrence rate after laparoscopic versus Shouldice repair of primary inguinal hernia. Br J Surg 92(9):1085–1091

Klinge U, Klosterhalfen B, Müller M, Ottinger AP, Schumpelick V (1998) Shrinking of polypropylene mesh in vivo: an experimental study in dogs. Eur J Surg 164(12):965–969

El-Dhuwaib Y, Corless D, Emmett C, Deakin M, Slavin J (2013) Laparoscopic versus open repair of inguinal hernia: a longitudinal cohort study. Surg Endosc 27(3):936–945

Schmedt CG, Sauerland S, Bittner R (2005) Comparison of endoscopic procedures vs Lichtenstein and other open mesh techniques for inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc 19(2):188–199

Bracale U, Melillo P, Pignata G, Di Salvo E, Rovani M, Merola G, Pecchia L (2012) Which is the best laparoscopic approach for inguinal hernia repair: TEP or TAPP? A systematic review of the literature with a network meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 26(12):3355–3366

Choi YY, Kim Z, Hur KY (2012) Learning curve for laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal repair of inguinal hernia. Can J Surg 55(1):33–36

Dallas KB, Froylich D, Choi JJ, Risa JH, Lo C, Colon MJ, Telem DA, Divino CM (2013) Laparoscopic versus open inguinal hernia repair in octogenarians: a follow-up study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 13(2):329–333

Mui WL, Ng CS, Fung TM, Cheung FK, Wong CM, Ma TH, Bn MY, Ng EK (2006) Prophylactic ilioinguinal neurectomy in open inguinal hernia repair: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 244(1):27–33

McCormack K, Scott NW, Go PM, Ross S, Grant AM, EU Hernia Trialists Collaboration (2003) Laparoscopic techniques versus open techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD001785

Leibl BJ, Däubler P, Schmedt CG, Kraft K, Bittner R (2000) Long-term results of a randomized clinical trial between laparoscopic hernioplasty and shouldice repair. Br J Surg 87(6):780–783

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animal performed by any of the authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, J.J., Way, J.A., Eslick, G.D. et al. Transabdominal Pre-Peritoneal Versus Open Repair for Primary Unilateral Inguinal Hernia: A Meta-analysis. World J Surg 42, 1304–1311 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4288-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4288-9