Abstract

Background

Between 2006 and 2008 the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program was implemented in colonic surgery in one-third of all hospitals in the Netherlands (n = 33). This resulted in enhanced recovery and a decrease in hospital length of stay (LOS) from a median of 9 days at baseline to 6 days at one-year follow-up. The present study assessed the sustainability of the ERAS program 3–5 years after its implementation.

Materials and methods

From the 33 ERAS hospitals, 10 initially successful hospitals were selected, with success defined as a median LOS of 6 days or lower and protocol adherence rates above 70 %. In 2012 a retrospective audit of 30 consecutive patients was performed in each of these hospitals. Sustainability of the ERAS program was assessed on hospital level, using median hospital LOS, protocol adherence rates and time to functional recovery. Data were compared with the implementation phase data.

Results

Overall median LOS in the selected hospitals increased from 5.25 days (interquartile range [IQR] 4.75–6.00; min, 4.00—max, 6.00) to 6 days (IQR 5.00–7.00; min, 5.00—max, 8.00), but this change was not significant (p = 0.052). Time to functional recovery was equal in both phases: median 3.00 days (p = 0.26). Protocol adherence decreased from 75 to 67 % (p = 0.32). Especially adherence to postoperative care elements dropped considerably.

Conclusions

Despite a slight decrease in protocol adherence, the ERAS program was sustained reasonably well in the 10 selected hospitals, although there was quite some variation between the hospitals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many innovations have been implemented in the last decades, some more successful than others [1, 2]. Implementing an effective innovation into daily routines is, generally speaking, a dynamic and difficult process [3], and results may vary between organizations CON [4–6]. Furthermore, once implementation has succeeded there often is a tendency for relapse into old routines after the implementation activities have ended [7]. Research shows that in public health 40 % of all innovations are not sustained after termination of the initial implementation activities and funding [8]. This may be seen as a waste of time and money spent on the implementation. Besides the financial implications, the discontinuation of successful innovations might result in less than optimal care for patients, and it may cause frustration and diminish the support for future healthcare indicatives. Therefore, it is important that achieved benefits of an effective intervention are sustained after implementation. Although sustainability is an important subject in healthcare, there is no standard definition of sustainability [9]. It can be seen as “holding the gains” or “maintaining health benefits” and “continuation of the program activities within an organizational structure”CON [7, 9–11]. Sustainability of change exists when a newly implemented innovation continues to deliver the achieved benefits over a longer period of time, certainly does not return to the usual processes and becomes “the way things are done around here,” even after the implementation project is no longer actively carried out or until a better innovation comes along [12]. Furthermore, little is known about differences in sustainability success between hospitals, although a recent study suggested that insight into practice variation might improve the quality of care [13]. Surgical research tends to focus on overall results on the patient level, but because it has been suggested that organizations differ in their innovative climate and urge to implement new insights, it is likely that changes are sustained in varying degrees in different hospitals.

Surgery, as other specialties, is a domain in healthcare that has a high turn-around and a fast-changing character, with many innovations in technology [14]. Many innovations have been implemented in recent decades, such as minimally invasive surgery, endovascular surgery, and ancillary innovations aimed at improving quality of careCON [15–17]. Another example is the introduction of evidence-based multimodal perioperative care protocols, leading to an enhanced recovery and a reduction in hospital length of stay (LOS) in surgical patientsCON [18–22]. In the Netherlands, the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program was implemented in colonic surgery in 33 hospitals by means of a generic implementation strategy, the so-called Breakthrough Series. This resulted in enhanced recovery and an overall decrease in LOS after colonic surgery, from a median of 9 days at baseline to 6 days after one year, at the end of the implementation activities [23]. To study whether these results were sustained we assessed the achieved benefits of the perioperative care program three to five years after the implementation activities had been ended.

Methods

For the long-term follow-up measurement we used a retrospective observational study design. As part of the primary implementation project (the Breakthrough Study) the participating hospitals had already performed a retrospective baseline measurement of surgical care during the year before implementation (2005–2007; pre-implementation phase), and a prospective measurement of care performed during the implementation project (2006–2009; implementation phase). This Breakthrough Study ended in 2009. During the present study a retrospective analysis of surgical care was performed (2012; post-implementation phase). This long-term evaluation study was not planned as part of the initial Breakthrough Study; as such, it is independent of the original implementation study. To assess sustainability, results of the post-implementation phase were compared with the implementation phase. Results of the pre-implementation phase were presented for further information.

Ethical approval and informed consent

The Medical Ethical Committee of the University of Maastricht Granted approval for the project, METC 11-4-015.10. The privacy of the included patients was protected, and all data were coded and processed anonymously. Medical files with explicit patient statements that their medical information should not be used for clinical research were not included.

Participants

Hospitals

Ten hospitals were selected out of the total of 33 hospitals that had participated in the original Breakthrough Study. Only those hospitals were selected in which the primary implementation strategy was successfully executed. Initial implementation success was defined as follows: (1) a median LOS of 6 days or lower, (2) an overall protocol adherence above 70 %, and (3) at least 40 patients treated within the year of the implementation project.

Patients

For the post-implementation audit of each selected hospital, 30 consecutive patients undergoing colorectal surgery were included from the period 2011–February 2012. The same inclusion and exclusion criteria were used as in the primary implementation project: patients undergoing elective colorectal resection above the peritoneal reflection for benign or malignant disease were eligible for this study. Patients who needed emergency surgery and those requiring an end or diverting ileostomy or colostomy were excluded.

Outcomes

Sustainability was assessed according to three different outcomes: LOS, functional recovery, and protocol adherence rates. These results were compared with the results of the audit during implementation. We defined sustainability at the hospital level as being reached if the performance in the post-implementation phase was equal to or better than performance during the implementation phase.

Length of stay

Hospital length of stay was defined as the number of nights in hospital after surgery.

Time to functional recovery

Time to functional recovery (FR) was defined as the number of postoperative days until adequate pain control requiring oral analgesia only was achieved, as well as tolerance of solid foods and independent mobility sufficient to perform activities of daily living at the preoperative level.

Protocol adherence

The performance on key elements of the ERAS program was evaluated per element.

Data collection

Data collection started in March 2012. Hospitals were asked to provide a list of the last consecutive 30 patients who underwent elective colonic surgery, until the start of data collection. Data were extracted from the (electronic) patient files by two of the authors (F.G., S.A.). In the beginning this was done as a joint exercise to guarantee standardization of auditing methods. At a later stage, the data collection was done by one of these two authors separately.

Statistical analysis

Differences between the pre-implementation, implementation, and post-implementation phases were checked using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and the Chi square test for categorical variables. Differences in LOS and FR between the implementation phase and the post-implementation phase were analyzed with log rank tests, as LOS and FR were censored if the patient had died. A p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. The unit of analysis was hospital level, to assess the variation between hospitals. Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations (SD) or as median and range in the case of skewed data. Both LOS and FR are presented as median of the median per hospital. Interquartile ranges and minimum and maximum values are presented between bars. Number and percentage were used for categorical variables. All analyses were performed with SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). In the pre-implementation phase, fewer data were available for analysis. These are reported as not available/missing (NA) in the Results section.

Results

The 10 selected hospitals participating in the project included 7 teaching hospitals and 3 non-teaching hospitals. In the pre-implementation phase 450 patients in total were included. In the implementation phase 523 patients were included, with 297 patients remaining in the post-implementation phase. Overall demographics are shown in Table 1. In the post-implementation phase significantly older patients were included, with more patients in American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade III/IV and more patients with a malignancy (p < 0.001). Also, in the post-implementation phase, more than half of the surgical procedures were performed laparoscopically, whereas some 40 % of procedures were laparoscopic during the implementation phase (p = 0.45).

Results on LOS, FR, and protocol adherence are shown on hospital level (Table 2).

Length of stay

Overall, the median LOS increased from 5.25 days (IQR P25 4.75– P75 6.00; min 4.00; max 6.00) in the implementation phase to 6.00 days (IQR P25 5.00–P75 7.00; min 5.00; max 8.00) in the post-implementation phase, but this difference was not significant (p = 0.052).

Hospital LOS was sustained in three hospitals: two hospitals achieved a further reduction in LOS in the post-implementation phase, and one hospital showed an equal LOS. Seven hospitals showed an increase in LOS in the post-implementation phase. One of these hospitals fell back to the same level noted before the implementation phase (Fig. 1).

Functional recovery

Overall FR was reached in a period of median 3.00 days (IQR P25 2.88–P75 3.00; min 2.00; max 4.00) in the post-implementation phase, which was equal to the median FR 3.00 (IQR P25 3.00–P75 3.50; min 3.00; max 4.00) in the implementation phase. Time to FR was sustained in eight hospitals: three hospitals showed a further reduction of FR of one day, and time to FR remained equal in five hospitals. One hospital showed an increase in time to FR of one-and-a-half day. In one hospital no data were available for FR in the implementation phase. Overall, the proportion of patients recovered on postoperative day two increased from 18 to 37 % (range 27–52 %), and increased on postoperative day three from 54 to 64 % (range 40–85 %). These results differed markedly between hospitals, the proportion of patients showing FR on day two in the best-performing hospital being 52 %, while FR was 27 % in the hospital with the poorest performance. The same observation was made on the third postoperative day: in the best-performing hospital 85 % of patients were functionally recovered on the third postoperative day, whereas in the least-performing hospital 40 % of patients were functionally recovered on this day (Fig. 2).

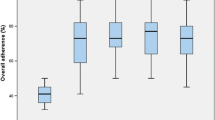

Protocol adherence

Overall mean protocol adherence rate in the post-implementation phase was 67 % (SD 6.3 min 56 %; max 73 %), whereas it was 75 % (SD 7.6 min 64 %; max 87 %) in the implementation phase. Overall adherence in the preoperative and perioperative period remained almost equal in the implementation and post-implementation phases, but postoperative adherence dropped considerably in the post-implementation phase (Table 3). Particularly, the cessation of IV fluids on the first postoperative day (from 36 to 9 %), mobilization for more than 3 h (90–38 %), and resumption of solid foods (65–37 %) were protocol elements less adhered to. There was a wide variation between hospitals. Three hospitals sustained their performance on protocol adherence, two hospitals showed a reduction of less than 10 %, and five hospitals showed a reduction of adherence of more than 10 % (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The present study shows that initial results of a large-scale implementation project of the ERAS program were sustained reasonably well, although there was a large variation among hospitals. The primary aim of the evidence-based perioperative care program was to decrease the time to postoperative recovery and, subsequently, the time of hospitalization. The present long-term follow-up demonstrated that time to recovery was sustained in most hospitals, whereas the achieved reduction in LOS was not fully sustained in all hospitals. The implementation successes in protocol adherence were not very well sustained, as, in most hospitals, adherence rates dropped in the post-implementation phase.

With regard to LOS, other studies showed a median of 2 days after colonic surgery within a fast track protocol [20, 24], but these results were not reached in the present study. In the Netherlands, the overall median LOS after colonic surgery was 7–8 days in 2012 [25]. Although the optimum was not reached, 9 of the 10 hospitals in the current study performed considerably better with respect to LOS than the rest of the Netherlands, and LOS of only one hospital increased to 8 days. These results suggest that the ERAS program is still effective in the participating hospitals. The fact that a LOS of 2 days after colonic surgery was not reached could be due to the healthcare policy regarding reimbursement in the Netherlands. The system does not stimulate discharge of patients as soon as they are capable of going home (FR). Evaluation of the initial implementation results showed that all hospitals had difficulties with discharging patients at the moment of FR [23]. The present study shows that the gap between FR and discharge of postoperative patients remains large. More research is needed to determine possible reasons for this gap that prohibits reaching a hospital LOS of 2 days, as seen in other countries.

Despite a significant increase in the age of the patients and a larger proportion of ASA III/IV patients who were operated and cared for according to the ERAS program, LOS and FR were sustained in several hospitals. This might be explained by the proportion of patients operated laparoscopically being significantly larger in the post-implementation phase compared with the implementation phase, again with a wide variation among hospitals (range 21–90 %).

In contrast to the preoperative and perioperative adherence rates of the ERAS program, the adherence rates to postoperative care elements in our series dropped remarkably, similar to other studies [26]. In particular, adherence to three protocol elements deteriorated: (1) mobilization of patients for more than 3 h on the first postoperative day, (2) cessation of IV fluids on the first postoperative day, and (3) resumption of solid foods. These postoperative protocol elements were also those that were the most difficult to adhere to in the implementation phase [23]. Postoperative mobilization of patients and the cessation of IV fluids are elements in postoperative care that are influenced by multiple factors, such as patient characteristics, the doctors on the ward, the nurses, and physiotherapists. The number of professionals involved may be causal for the difficulty to sustain the required changes, particularly if there is no specific attention to the continuation of these elements.

Interestingly, the best performing hospital with regard to length of stay and recovery showed a low protocol adherence rate, whereas the least performing hospital showed a high adherence rate. It therefore remains unclear what elements of the ERAS program are the determinants of success of implementation.

Hospitals in the present study were selected because they initially showed good results on LOS and adherence rates. This suggests that implementation of the ERAS program caused a change in the mind-set of healthcare professionals in these hospitals [27, 28], although this kind of change has been suggested to be difficult [1, 29, 30]. After the initial implementation, the ERAS program needs to be normalized within the local hospital organization. Because results on sustainability of the ERAS program varied remarkably, it could be argued that this change in mind-set was not equally strong in every hospital.

A strength of the study is that we analyzed surgical care 3–5 years after the primary implementation of the ERAS program. The median follow-up time for interventions aimed at improving quality of care is generally less than one year [31], although a recent review shows that more than 50 % of sustainability studies are performed 2 years or later after implementation [32]. By expanding the follow-up period, more insight is gained regarding the long-term impact of implementing change and its sustainability. If an innovation is effective the first year after implementation but the effect dies out in the succeeding years, the benefit of the innovation becomes questionable.

Another strength of the study is the analysis on the hospital level. Most surgical implementation studies present results on the patient level, overlooking institutional variation [6]. By analyzing results on the hospital level, more detailed insight is gained into the variation in performance of the ERAS program in each hospital. The choice to analyze the data on the hospital level, however, made it impossible to develop a reliable multivariate regression model. This means that the influence on LOS of important factors such as laparoscopy and rising patient age was not assessed.

A further strong point of the present study is the definition of sustainability. We applied a narrative definition based on the literature, and in light of this definition we specified endpoints applicable for this specific case, the ERAS program for colonic surgery. Choosing specific endpoints is necessary for a transparent and meaningful evaluation of sustainability. We realize, however, that our endpoints cannot be applied universally. Another issue concerning these endpoints was the use of three outcome parameters. Because all three are influenced by several factors other than the patient alone, it was impossible to conclude which outcome parameter is the most important one. Therefore, we did not provide an overall result regarding sustainability, but assessed sustainability according to these three parameters separately.

A weakness of the current study is the retrospective character of the audit. A problem with auditing patient files retrospectively could be that not all process indicators were recorded accurately, meaning that the actual performance on care elements could have been underestimated by a lack of registration. However, by choosing a retrospective audit, a Hawthorne effect was prevented. This is the phenomenon that a team of professionals is improving its performance due to awareness of being evaluated. Thus, although performance on some process indicators may have been underestimated, the retrospective audit provides a more honest insight into the actual care provided.

Another weakness of the study is the restriction to a subsample of hospitals. It was not possible to assess the sustainability of the ERAS program in all 33 hospitals because of the limitations of time and resources. We therefore chose the best-performing hospitals at the time of primary implementation of the ERAS program, as successful primary implementation is a prerequisite for a sustainability evaluation in the long term. We assume that the overall sustainability of all hospitals in the ERAS group is lower than the study group of the 10 best-performing hospitals, although it is theoretically possible that the other 23 hospitals kept developing colonic surgery after the implementation phase, and showed a delayed success with reduction in median LOS and FR because of a slow learning curve. This could mean that these results might not be generalizable to all hospitals.

Conclusions

This study shows that the ERAS program was reasonably well sustained, although results varied remarkably between hospitals. Six years after the implementation of the ERAS program median LOS increased from 5.25 to 6 days, but this result was not statistically significant. There was, however, a large variation among hospitals regarding LOS, time to FR, as well as protocol adherence.

References

Grol R, Wensing M (2004) What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Med J Aust 180(6 Suppl):S57–S60

Wilson KD, Kurz RS (2008) Bridging implementation and institutionalization within organizations: proposed employment of continuous quality improvement to further dissemination. J Public Health Manag Pract 14:109–116

Grol R, Grimshaw J (2003) From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet 362(9391):1225–1230

Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B (1998) Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care 7:149–158

Scott-Findlay S, Golden-Biddle K (2005) Understanding how organizational culture shapes research use. J Nurs Adm 35:359–365

Rangachari P, Rissing P, Rethemeyer K (2013) Awareness of evidence-based practices alone does not translate to implementation: insights from implementation research. Qual Manag Health Care 22:117–125

Scheirer MA (2005) Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. Am J Eval 26:27

Schell SF, Luke DA, Schooley MW et al (2013) Public health program capacity for sustainability: a new framework. Implement Sci 8:15

Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Bone LR (1998) Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Educ Res 13:87–108

Gruen RL, Elliot JH, Nolan ML et al (2008) Sustainability science: an integrated approach for health-programme planning. Lancet 372(9649):1579–1589

Rabin BA, Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D et al (2008) A glossary for dissemination and implementation research in health. J Public Health Manag Pract 14:117–123

Ament SM, Gillissen F, Maessen JMC et al (2012) Sustainability of healthcare innovations (SUSHI): long term effects of two implemented surgical care programmes (protocol). BMC Health Serv Res 12:423

Tomson CR, van der Veer SN (2013) Learning from practice variation to improve the quality of care. Clin Med 13:19–23

Rogers WA, Lotz M, Hutchison K et al (2014) Identifying surgical innovation: a qualitative study of surgeons’ views. Ann Surg 259:273–278

Cahill RA, Lindsey I (2011) Operative innovations for colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 13(Suppl 7):1–2

Mathis KL, Boostrom SY, Pemberton JH (2013) New developments in colorectal surgery. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 29:72–78

Atallah S, Nassif G, Polavarapu H et al (2013) Robotic-assisted transanal surgery for total mesorectal excision (RATS-TME): a description of a novel surgical approach with video demonstration. Tech Coloproctol 17:441–447

Fearon KC, Ljungqvist O, Von Meyenfeldt M et al (2005) Enhanced recovery after surgery: a consensus review of clinical care for patients undergoing colonic resection. Clin Nutr 24:466–477

Kehlet H (1997) Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth 78:606–617

Kehlet H, Mogensen T (1999) Hospital stay of 2 days after open sigmoidectomy with a multimodal rehabilitation programme. Br J Surg 86:227–230

Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Dejong CH et al (2010) The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for patients undergoing major elective open colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr 29:434–440

Vlug MS, Wind J, Hollmann MW et al (2011) Laparoscopy in combination with fast track multimodal management is the best perioperative strategy in patients undergoing colonic surgery: a randomized clinical trial (LAFA-study). Ann Surg 254:868–875

Gillissen F, Hoff C, Maessen JM et al (2013) Structured synchronous implementation of an enhanced recovery program in elective colonic surgery in 33 hospitals in the Netherlands. World J Surg 37:1082–1093. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-1938-4

Rossi G, Vaccarezza H, Vaccaro CA et al (2013) Two-day hospital stay after laparoscopic colorectal surgery under an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway. World J Surg 37:2483. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-2155-x

Jaarrapportage (2012) Dutch surgical colorectal audit (DSCA). http://www.clinicalaudit.nl/jaarrapportage/2012/

Hendry PO, Hausel J, Nygren J et al (2009) Determinants of outcome after colorectal resection within an enhanced recovery programme. Br J Surg 96:197–205

Biffl WL, Spain DA, Reitsma AM et al (2008) Responsible development and application of surgical innovations: a position statement of the Society of University Surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 206:1204–1209

Ahmed J, Kahn S, Lim M et al (2012) Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols—compliance and variations in practice during routine colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis 14:1045–1051

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Walker AE et al (2002) Changing physicians’ behavior: what works and thoughts on getting more things to work. J Contin Educ Health Prof 22:237–243

Polle SW, Wind J, Fuhring JW et al (2007) Implementation of a fast-track perioperative care program: what are the difficulties? Dig Surg 24:441–449

Hovlid E, Bukve O, Haug K et al (2012) Sustainability of healthcare improvement: what can we learn from learning theory? BMC Health Serv Res 12:235

Wiltsey Stirman S, Kimberly J, Cook N et al (2012) The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci 7:17

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) and The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) for financial support (project number 171103004). In addition, they thank all hospital personnel who participated in this study and A. Kessels, who provided statistical advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gillissen, F., Ament, S.M.C., Maessen, J.M.C. et al. Sustainability of an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Program (ERAS) in Colonic Surgery. World J Surg 39, 526–533 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-014-2744-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-014-2744-3