Abstract

Background

The need for surgical care far exceeds available facilities, especially in low income and poor countries. Limited data are available to help us understand the extent and nature of barriers that limit access to surgical care, particularly in the Asian subcontinent. The aim of this study was to understand factors that influence access to surgical care in a low-income urban population.

Methods

An observational cross-sectional study was conducted on 199 consecutive patients admitted for elective surgery from February to April 2010 to identify the presence and causes of delay in accessing surgical care.

Results

The median duration of symptoms were 7 and 4 months in women and men, respectively. The odds of delay between the onset of symptoms and seeking initial health care (first interval) is twice as likely for women than for men [52.7 vs. 37.5 %, odds ratio (OR) 1.9]. Lack of knowledge regarding treatment options [OR 3.8; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.4–10.3] and about disease implications (OR 2.4; 95 % CI 1.2–4.8) were cited most often. A second interval of delay (time from when surgery was first advised to the surgery) was reported by 123 (61.8 %) patients. Financial constraints (29.6 %) and environment-related delays (10.6 %) were cited most often. More women than men thought there was a second delay interval (73 vs. 58 %). The odds of women having more co-morbid conditions were nearly 4.7 times that of men (95 % CI 1.5–15.1).

Conclusions

A complex interaction of factors limits access to surgical care in developing countries. Women appear to face greater hurdles to accessing health care. Understanding local factors is essential to make care accessible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Deficiencies in access to surgical care have been highlighted in recent years as a contributing factor to increased morbidity and mortality, particularly in low- to middle-income countries (LMICs). The Global Burden of Disease study estimated that 11 % of disease conditions are amenable to surgery [1]. This estimate is expected to rise steadily in view of the epidemiologic transition exemplified by the increasing incidence of ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, cancer, and injuries due to road traffic accidents [2].

Surgery has long had an important role in traditional “strongholds” of public health. For instance, obstetric emergencies often require urgent surgical intervention for successful outcome. In fact, access to timely and adequate surgical care is likely to have a greater impact on decreasing maternal mortality than routine antenatal screening and care [2]. Other conditions equally amenable to surgical intervention have not received the same attention.

A major concern is the disparity of access to surgical care, which is underscored by far lower volumes of surgical procedures performed in poor versus rich countries [3]—specifically the LMICs where most of the global population live. In some settings, the barriers to accessing surgical care have been well documented. Poor infrastructure, lack of physical resources and severe shortage of trained health care professionals are widely reported factors [3, 4].

Recognizing the huge unmet burden of surgical disease and the growing evidence for the need of improved surgical care, the Global Initiative for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (GIEESC) was established at the World Health Organization with the objective of improving emergency and essential surgical care at resource-limited health care facilities. Establishment of the GIEESC is an important milestone in addressing the health system and provider level barriers to surgical care (i.e., by working at the health system and provider level to improve the quality and safety of essential surgical and anesthesia care). It has provided a platform for a globally agreed-upon infrastructure for surgical care that can be adapted and implemented in LMICs.

Patient-level barriers, however, still dictate whether the local population utilizes an existing facility. Along with health system and provider level reforms, it is important to understand the real and perceived barriers to accessing care in local settings from the patient’s perspective before establishing or reorganizing a surgical health delivery system. Recent data from the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey indicate that the foremost reasons for not accessing skilled health care are cost, distance/lack of transport, and not thinking it was necessary [5]. In a rural setting of Pakistan, a population-based survey indicated that lack of education and awareness, cultural factors, poverty, and inadequate health sector capacity contribute to limiting the individual accessing surgical care [6].

Few studies estimating the unmet need for surgical care in developing countries have been published. A population-based survey done in catchment areas of district hospitals across Pakistan, published in 1987 [7], found that the rate of operations was 124/100,000 population. This translates into 1.5–9.0 % of the rate of operations in Western countries during the same time period. The available number of surgeons in Pakistan was also found to be much lower, at a ratio of 0.36/100,000 (compared to 1/80 in the United States). A recently published overview of the challenges faced when providing surgical care in Pakistan highlights the critical shortage of health care workers as only one of the many factors that have led to the current dismal state of affairs [8]. Workforce limitations are expected to increasingly influence clinical care in developed countries during the coming years [9]. To a large extent, an attempt to mitigate this situation by allowing preferential immigration for health care professionals is underway. However, it is compounding an already critical shortage of health care workers in many developing countries, including Pakistan.

Pakistan is the sixth most populous country in the world, with an estimated population of 187 million in 2011. The rapidly increasing urbanization has led to more than a third of the population living in cities, making Pakistan one of the most urbanized countries in South Asia [10]. Karachi is the largest city of Pakistan and ranks among the 20 largest metropolitan areas in the world [11]. Population estimates vary from 13 million to 20 million for this developing megacity, and the larger metropolitan area has an estimated population of 25 million [12]. This multi-ethnic city is growing rapidly because of a combination of internal rural–urban migration, refugee populations, and indigenous growth [12].

The Indus Hospital is located in Korangi, a low-income area with a population of ~2.5 million people living within a 1 km radius. The majority of the population is comprised of migrant workers and their families, including practically every ethnic group in the country. This cultural diversity translates into differences in social structure and norms and hence in health-seeking behavior. Several public and private clinics and hospitals provide health facilities, but the Indus Hospital is the only tertiary care center in that area, providing a wide range of medical and surgical care completely free of cost. This includes medicines, diagnostic tests, supplies, and food for admitted patients. The quality of care provided is comparable to some of the best private-sector hospitals in the city. The facility is funded by private philanthropists, mainly based in the country.

Even in the presence of a free-of-cost, high-quality facility, there are many barriers and delays to seeking care. Health-seeking behavior is complex and often influenced by traditional beliefs. The quality of, and accessibility to, a facility are factors that influence but do not wholly determine how patients use a facility. Understanding these patient level barriers in the presence of a quality health care infrastructure can facilitate developing local health care delivery models that are directed by the needs of the population and are relevant not only to a cosmopolitan city but across the country and region. The aim of this study was to understand the specific challenges that determine health care access in the urban setting of Karachi.

Materials and methods

Study design

A cross-sectional survey was conducted from February to April 2010 at Indus Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. Consecutive patients admitted to all surgical services for elective procedures under general anesthesia were recruited. The study team approached eligible patients. Once informed consent was obtained, a standardized questionnaire in Urdu (Pakistan’s national language) was administered. Patients with acute surgical conditions or trauma were excluded from this study. Where the patient was a child, information was obtained from the parents.

Sample size

Because of the paucity of information from Pakistan or regional countries regarding delay in seeking health care for surgical conditions, the sample size was calculated using Slovin’s formula. The formula is based on the number of surgeries performed at the hospital during the 3 months prior to our data collection with a 7 % error tolerance and 10 % refusal to participate. Hence, a sample size of ~202 patients was required.

Data collection

Information on the sociodemographic profile of enrolled patients was collected. Questions were asked that pertained to symptoms and their severity as perceived by the patients. Interviewers administered the questionnaire verbally because literacy levels are low in our population. Explanations were provided when necessary. Symptom severity was documented as perceived by the patient. They were subjectively classified as symptoms that did not interfere with daily activities (mild), those that limited daily activities to some extent (moderate), and those that did not allow daily tasks to be performed (severe). The questionnaire asked for details about the health care sought from the time of onset of the symptoms. The time period from the initial onset of symptoms to the initial presentation to any type of health provider was defined as the “first interval.” The time from being first advised to have surgery to performance of the operation was defined as the “second interval.” Delays in receiving care during these two periods were recorded as they were perceived by the patient. Open-ended questions were asked to understand patients’ perceptions and reasons for delays, if any.

Data analysis and quality control measures

Open-ended questions and questions generating additional information were given codes by the study team. The complete data were single-entered using MS Excel. Data were imported into SPSS software (version 16; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) where analysis was performed. The χ 2 test and analysis of variance were used to assess for possible associations. Odds ratios for associations between sex and variables of interest were also computed.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol, questionnaire, and consent form were submitted to the institutional review board, and the study was started after approval was obtained. Respondents were ensured confidentiality and were briefed that their participation was voluntary with full rights to refuse enrollment or withdraw from the study with no impact on the care being provided to them.

Results

A total of 202 interviews were conducted during the study period. Three interviews were not included in the analysis because of incomplete information. The median ages as reported by the patient or their family members were 30 years for men and 34 years for women (Table 1).Three-fourths of the patients were men (72.4 %). The duration of reported symptoms ranged from 1 day to 30 years (median 5 months). The majority of the women were admitted for orthopedic surgery (60 %) whereas the distribution for men ranged from orthopedics (38 %) to urology (19 %), pediatric surgery (16.1 %), and general surgery (12.6 %) (Table 1).

Nearly 25 % of the patients reported either mild or moderate symptoms. Another 31 % reported severe symptoms from the onset. Almost 13 % of the patients reported ever having mild symptoms that progressed to moderate symptoms, 5 % reported progression from moderate to severe symptoms, and 2 % reported progression from mild to moderate to severe symptoms. The median duration of any symptoms was 7 months for women and 4 months for men (Table 1).

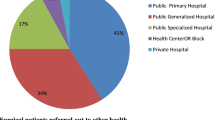

Nearly 78 % of the men stated that a hospital was their first point of care for treatment of their condition, whereas only 58 % of the women did so. Almost 33 % of the women and 18 % of the men sought their first treatment advice from a general physician (GP). More than 92 % of the study participants were first advised to have surgery in a hospital setting (Table 2).

The odds of delay between onset of symptoms and seeking initial health care was twice as likely for women than for men [52.7 vs. 37.5 %, odds ratio (OR) 1.9]. Statistically significant reasons for the first-interval delay were lack of knowledge regarding treatment options [OR 3.8; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.4–10.3] and lack of knowledge about disease implications (OR 2.4; 95 % CI 1.2–4.8) (Table 3).

Overall, a second-interval delay was reported by 123 (61.8 %) patients. No association was observed between reported delays and the severity of the presenting symptoms for this interval. Reasons for the second-interval delay are detailed in Table 3, with financial difficulty being the most commonly cited overall reason (29.6 %) followed by environment-related delays (10.6 %), which included access issues, geographic limitations, and city disturbances. Almost 73 % of the women (vs. 58 % of the men) perceived that there was a delay between the times they were first advised surgery to the surgery itself. The odds of women having more co-morbid conditions were nearly 4.7 times that of men (95 % CI 1.5–15.1). Reasons for delay given by the patients were recorded verbatim; English translations of some responses are shown in Table 4 to give an insight into the complex nature of problems faced by patients.

A larger percentage of delays for both intervals were reported by women than by men. No association was seen between patient age (pediatric vs. adult age groups) and the first- or second-interval delays. Similarly, no association was found between surgical specialties and the first- or second-interval delays (data not shown).

Discussion

This study clearly demonstrated that financial challenges are only one of the many barriers to accessing health care. Lack of access to health care is generally equated with an inability to pay for services. It is clear, though, that patterns of seeking medical care are guided by a complex interaction of multiple factors. Our study showed that financial barriers contribute less to the reasons for delay during the first interval, when advice is often sought from locally accessible doctors or facilities as the first port of call. Once it has been determined that there is a need for surgical intervention that is usually available at a greater distance from home, financial limitations seem to play a larger role. Environment-related issues—geographic location, access issues, city disturbances (viewed separately from purely financial concerns)—accounted for only a small percentage (5.6 %) of the reasons for delay during the first interval but to nearly 14.5 % of the delays for women during the second interval (vs. 9.1 % among men).

Barriers to accessing health facilities have been well studied for rural communities [6, 13–15], but low-income urban slum populations face equally prohibitive, if different, challenges that are poorly documented. Data from Kenya has shown worse health indicators for the urban poor than for their rural counterparts [14]. It is obvious that low-income and poor urban populations face unique challenges to accessing health care that are more pronounced in acute or emergency settings but also play a significant role when seeking care for nonurgent medical conditions. Interestingly, access issues were less of a contributing factor for women during the first-interval delay—when they mainly saw general physicians and local healers as their first treatment advice point—than when they were required to be admitted for surgery at a tertiary hospital. Mobility and access to health care at some distance from their home can influence the decision of a family to seek care outside their neighborhood, particular during the night.

Barriers vary from one population to another. Even within a given community, the challenges and constraints that the members of one household face in accessing care may vary from those in a neighboring household. Factors that have been found to influence outcomes in surgical patients in the developed world include socioeconomics, access to insurance, sex, race and ethnicity, language, and education [9, 15–17]. These factors influence patient–provider communication, which is a key determinant in how patients use existing facilities. In our study population, these aspects are clearly highlighted in the patients’ comments cited in Table 4.

Women tend to delay seeking health care more than men. This sex difference was noted during both the first and second intervals in our study. Women, especially those belonging to a low socioeconomic status with low literacy are often not allowed to leave home or travel a distance to seek care without being accompanied by a male member of the family [18, 19]. Men of the families are usually at work during the daytime, which often leads to nonacute health issues being neglected. In some communities, the restriction of the purdah, or veil, has been shown to prevent mothers from accessing treatment for themselves or their children [19, 20]. Access issues studied in women seeking emergency obstetric care in rural Haiti show that lack of transportation was a deciding factor in seeking health care in a small number of cases [13]. Potential interventions to lessen these barriers may include education of the community and other opinion leaders on the need for women to use health services under certain circumstances. Programs to empower women through education and health awareness may also be helpful in breaking down these barriers to seeking care [18].

Recognizing the challenges highlighted by this study, our institution is looking to expand in the catchment population with a network of outreach clinics and teams, providing an easier point of initial contact between patient and provider. As the significant hurdle of distances and need to travel out of the community will be addressed through this strategy, it is hoped that especially women will benefit from this network. Moreover, our institution is committed to increasing the number and retention of female specialists at the tertiary care facility, which is likely to encourage female patients in our conservative society to seek specialist care.

A major reason for delay reported by patients in our series, especially for the first interval, was the lack of awareness of disease implications and available treatment options. This is a reflection of the lower levels of education in our catchment population but, more importantly, the influence of age-old remedies and perceptions that still shape the approach to seeking health care. During this survey, we did not ask the respondents for their educational qualifications or duration of schooling. However, a detailed baseline survey done in the catchment population of our institution indicates that 67 % of respondents are illiterate and 58 % have not received any formal schooling [21]. Given this scenario, we need to initiate focused campaigns in simple, local language that address common health issues and educate the general population. Such a campaign would have a positive impact on seeking early treatment at an appropriate facility. A population more aware of the disease and its complications would be more willing to present to a health care facility and seek help sooner.

General practitioners comprise an important front line of health care. As many as 80 % of our population go to GPs for their initial evaluation and treatment, especially for minor ailments [22]. GPs, who are doctors with minimal or no formal training following graduation from medical college, constitute ~85 % of the registered doctors in Pakistan. Continuing medical education and integration of GPs into a better referral network would improve their ability to diagnose and refer patients appropriately for surgical care.

Karachi has a large, mostly uncontrolled private health sector. Prices vary, but even more variable is the quality of care that is offered at these facilities. Public sector hospitals are meant to be free of cost, but even at these facilities patients are required to pay for consumables, medicines, and most diagnostic tests. These expenses are beyond the ability of a majority of the population, leading them to sideline nonemergent conditions. Anecdotally, surgeons at our facility have seen many patients with long-standing surgical problems seek care when the hospital opened for the first time and once the financial barrier was removed. The quality of the hospital plays a critical role in determining access. Facilities that are below par with respect to quality, capacity, and sensitivity are themselves “the problem” [23]. It is clear that even if a facility is free of cost, its utilization by the community will be suboptimal if it is perceived to be providing poor quality or substandard care.

The challenge of providing surgical care in developing countries involves not only providing safe surgical services at all levels of health care but also ensuring that accessibility to these services is maximized. The district general hospital model recommended as the cornerstone of surgical care in the Bellagio report [24] is an excellent way to focus resources in centers throughout the catchment population. It allows commonly seen elective operations and most emergency surgery to be performed safely and effectively at the district level. Building on this, GIIESC emphasizes that training the trainers and setting minimum standards for surgical care are essential for a successful surgical care delivery program [25]. This concept is classically applicable to a rural community, but the model can be adapted to large urban populations with high-quality secondary-level care being provided completely free of cost in each major locality. It would allow the tertiary care centers to be reserved for handing those complex diseases that cannot be treated at the secondary-level hospitals. It is important to connect the secondary-level facilities to a strong community-based network that allows maximum utilization of these facilities by even the most marginalized sections of the catchment area. This has clearly been demonstrated in the Zamne Lasante model in Haiti [15]. Making sure that a facility is either free of cost or affordable to the local community is an essential first step. Ensuring that a minimum standard of quality is maintained is equally important. Even the poorest of the poor are quick to recognize substandard care and that it plays a major role in the utilization of a facility. Moreover, ensuring that these facilities are “user-friendly” and therefore as accessible as possible remains the main, and most difficult, challenge to address.

Limitations

Convenience sampling was used. Therefore, the patients interviewed may not reflect the barriers encountered by the population of the whole region. Also, because of a small sample size, we may have missed some variable at play, particularly in the stratified analyses. We recommend that the methods and results from our study be used in a larger, countrywide survey to assess this pressing issue in its entirety.

Conclusions

A number of factors are at play in delaying patients from seeking surgical care and having necessary procedures done. In this study, the factors included unawareness about the disease implications and treatment options, financial limitations, location of the health care facility, transport unavailability, travel costs, and cultural and religious barriers. Because of these hindrances patients usually wait until their symptoms are severe enough to seek help. For many surgical conditions this could mean increased rates of intraoperative and postoperative complications.

The barriers can be reduced by two main groups of interventions. First, providing education and information to individuals, households, and communities in a way of dealing with the information gaps may lead to better health-seeking behavior. Second, developing infrastructures to provide more accessible and affordable health care facilities can encourage patients to get essential care in a timely manner closer to their homes.

References

Mathers C, Fat DM, Boerma JT et al (2008) The global burden of disease: 2004 update, vol vii. World Health Organization, Geneva, p 146

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M et al (2006) Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 367:1747–1757

Spiegel DA, Gosselin RA (2007) Surgical services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 370:1013–1015

Ozgediz D, Jamison D, Cherian M et al (2008) The burden of surgical conditions and access to surgical care in low- and middle-in come countries. Bull World Health Organ 86:646–647

Anonymous (2008) Pakistan demographic health Survey 2006–07. National Institute of Population Studies and Macro International Inc., Islamabad

Ahmed M, Shah M, Luby S et al (1999) Survey of surgical emergencies in a rural population in the northern areas of Pakistan. Trop Med Int Health 4:846–857

Blanchard RJ, Blanchard ME, Toussignant P et al (1987) The epidemiology and spectrum of surgical care in district hospitals of Pakistan. Am J Public Health 77:1439–1445

Zafar SN, McQueen KA (2011) Surgery, public health, and Pakistan. World J Surg 35:2625–2634. doi:10.1007/s00268-011-1304-3

Ryoo JJ, Ko CY (2008) Minimizing disparities in surgical care: a research focus for the future. World J Surg 32:516–521. doi:10.1007/s00268-007-9421-8

UNDP (2007) Human development report 2007/2008. United Nations Development Programme, New York

Forstall RL, Greene RP, Pick JB (2009) Which are the largest? Why lists of major urban areas vary so greatly. Tijdschr Econ Soc Geogr 100:277–297

Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat (2008) World population prospects, the 2006 revision and world urbanization prospects: 2007 revision. New York

Barnes-Josiah D, Myntti C, Augustin A (1998) The “three delays” as a framework for examining maternal mortality in Haiti. Soc Sci Med 46:981–993

Center APaHR (2002) Population and health dynamics in Nairobi’s informal settlements. African Population and Health Research Center, Nairobi

Ivers LC, Garfein ES, Augustin J et al (2008) Increasing access to surgical services for the poor in rural Haiti: surgery as a public good for public health. World J Surg 32:537–542. doi:10.1007/s00268-008-9527-7

Bigby J, Ashley SW (2008) Disparities in surgical care: strategies for enhancing provider-patient communication. World J Surg 32:529–532. doi:10.1007/s00268-007-9386-7

Rogers SO Jr (2008) Disparities in surgery: access to outcomes. World J Surg 32:505–508. doi:10.1007/s00268-007-9382-y

Anonymous (2005) Pakistan, country gender assessment 2005. World Bank, Islamabad

Khan A (1999) Mobility of women and access to health and family planning services in Pakistan. Reprod Health Matters 7:39–48

Ensor T, Cooper S (2004) Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy Plan 19:69–79

Khan FS, Lotia-Farrukh I, Khan AJ et al (2013) The burden of non-communicable disease in transition communities in an Asian megacity: baseline findings from a cohort study in Karachi, Pakistan. PloS One 8:e56008

Marsh D, Hashim R, Hassany F et al (1996) Front-line management of pulmonary tuberculosis: an analysis of tuberculosis and treatment practices in urban Sindh, Pakistan. Tuber Lung Dis 77:86–92

Grossman J (1990) Health education: the leading edge of primary health care and maternal and child health. In: Wallace HM, Giri K (eds) Health care of women and children in developing countries. Third Party Publishing, Oakdale, pp 56–57

Bellagio Essential Surgery Group (2007) Conference: increasing access to surgical services in resource-constrained settings in Sub-Saharan Africa. New York, Rockefeller Foundation’s Bellagio Conference Center

WHO (2007) WHO meeting on global initiative for emergency and essential surgical care (GIEESC). Health Technology and Pharmaceuticals Cluster. World Health Organization, Dar-es-Salaam

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Sundus Iftikhar, who analyzed the data. The authors are grateful for all of the support provided by Indus Hospital and Interactive Research and Development.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Samad, L., Jawed, F., Sajun, S.Z. et al. Barriers to Accessing Surgical Care: A Cross-Sectional Survey Conducted at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. World J Surg 37, 2313–2321 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2129-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2129-z