Abstract

Background

Laparoscopy has been widely used for surgical repair of large paraesophageal hernias (PEHs). The technique, however, entails substantial technical difficulties, such as repositioning the stomach in the abdominal cavity, sac excision, closure of the hiatal gap, and fundoplication. Knowledge of the long-term outcome (>10 years) is scarce. The aim of this article was to evaluate the long-term results of this approach, primarily the anatomic hernia recurrence rate and the impact of the repair on quality of life.

Methods

We identified all patients who underwent laparoscopic repair for PEH between November 1997 and March 2007 and who had a minimum follow-up of 48 months. In March 2011, all available patients were scheduled for an interview, and a radiologic examination with barium swallow was performed. During the interview the patients were asked about the existence/persistence of symptoms. An objective score test, the gastrointestinal quality of life index (GIQLI), was also administered.

Results

A total of 77 patients were identified: 17 men (22 %) and 60 women (78 %). The mean age at the time of fundoplication was 64 years (range 24–87 years) and at the review time 73 years (range 34–96 years). The amount of stomach contained within the PEH sac was <50 % in 39 patients (50 %), >50 % in 31 (40 %), and 100 % (intrathoracic stomach) in 7 (9.5 %). A 360º PTFe mesh was used to reinforce the repair in six cases and a polyethylene mesh in three. In May 2011, 55 of the 77 patients were available for interview (71 %), and the mean follow-up was 107 months (range 48–160 months). Altogether, 43 patients (66 %) were asymptomatic, and 12 (21 %) reported symptoms that included dysphagia in 7 patients, heartburn in 3, belching in 1, and chest pain in 1. Esophagography in 43 patients (78 %) revealed recurrence in 20 (46 %). All recurrences were small sliding hernias (<3 cm long). In all, 37 patients (67 %) answered the GIQLI questionnaire. The mean GIQLI score was 111 (range 59–137; normal 147). Patients with objective anatomic recurrence had a quality of life index of 110 (range 89–132) versus 122 in the nonrecurrent hernia group (range 77–138, p < 0.01). Mesh was used to buttress the esophageal hiatus in nine patients. One patient died during the follow-up period. Five of the remaining eight patients (62 %) developed dysphagia, a mesh-related symptom. Three patients required reoperation because of mesh-related complications. Esophagography revealed recurrence in four (50 %) of the eight patients. GIQLI scores were similar in patients with recurrence (126, range 134–119) and without it (111, range 133–186) (p > 0.05).

Conclusions

Long-term follow-up (up to 160 months) in our study showed that laparoscopic PEH repair is clinically efficacious but is associated with small anatomic recurrences in ≤50 % of patients. Further studies are needed to identify the anatomic, pathologic, and physiological factors that may impair outcome, allowing the procedure to be tailored to each patient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since Dallemange first described laparoscopic fundoplication for treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in 1988, laparoscopy has become the preferred approach for surgical diseases of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, including achalasia, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and paraesophageal hernia (PEH). Laparoscopic repair of PEHs—which include types II, III, and IV hiatal hernias—was well defined and tailored during the 1990s, but it is associated with substantial technical difficulty [1]. The technique involves repositioning the stomach in the abdominal cavity, sac excision, closure of the hiatal gap, and fundoplication. Additional measures, such as crural reinforcement with mesh and gastropexy, remain controversial [2]. Initial successful experience encouraged the use of laparoscopy as the definitive approach for PEH, but the seminal report from DeMeester’s group in 2002 [3], which showed a 42 % recurrence rate, raised concerns about the risk of poor results. Over the past decade, the endoscopic approach to PEH and a number of additional topics (e.g., recurrence rate, use of mesh, quality of life) have continued to generate controversy [3–12]. Furthermore, the long-term outcome (>10 years) of this approach is not well known. In 2004, we analyzed the short-term outcome in terms of patient’s quality of life (QoL). We found a 20 % recurrence rate and an acceptable QoL index after a mean follow-up of 24 months [4]. The aim of this study was to evaluate the long-term results of laparoscopic PEH repair, primarily the hernia recurrence rate and the impact of the repair on QoL.

Materials and methods

We reviewed the prospective database of patients who underwent laparoscopic PEH repair between November 1997 and March 2007 in the Surgery Department at Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau. Our aim was to obtain a minimum follow-up period of 48 months. Patients reoperated on for recurrence were excluded. PEHs were classified according to the amount of stomach herniated into the thorax and were evaluated intraoperatively <50, >50, or 100 % (intrathoracic stomach).

Patients were diagnosed by means of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy or barium swallow. The 24 hour pH test and manometry were used selectively.

The surgical technique has been described previously [4]. It consists of routine excision of the hernia sac, dissection of the mediastinal esophagus, posterior closure of the esophageal hiatus, and 360º fundoplication. When the hiatal closure was assumed to be weak, it was selectively reinforced with mesh. We used keyhole-shaped PTFE mesh (Gore Dual Mesh; W.L. Gore, Flagstaff, AZ, USA) in the first six cases, but after observing several complications we switched to the use of a small 4 × 4 cm piece of low-weight polypropylene and polyglycolic acid mesh (Vypro; Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA) located posteriorly to the esophagus to buttress the pillars closure. A gastropexy was fashioned when the stomach could not be repositioned in the abdominal cavity. No esophageal lengthening techniques were performed.

In March 2011, an interview was scheduled with each the available patients, and a radiologic examination by barium swallow was performed. During the interview, the patients were questioned about the existence/persistence of symptoms (heartburn, dysphagia, regurgitation, and/or pain). An objective test—Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI), a well-validated QoL score test—was applied to all patients [12, 13]. All of the patients available to follow-up underwent barium esophagography that was evaluated by a single radiologist. Recurrence was defined as any migration of the stomach into the mediastinum. The hernia was then categorized as a sliding hernia or a PEH and was measured in centimeters.

The data were statistically analyzed with descriptive and comparative tests (Student’s t test, χ2 test) according to the requirements.

Results

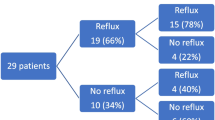

A total of 77 patients were enrolled in the study period, including 16 men (22 %) and 61 women (78 %). Their mean age at the time of PEH repair was 63 years (range 24–87 years), and the mean age at interview was 73 years (range 34–96 years) (Fig. 1).

Surgery was carried out on an elective basis in all patients. The size of the PEH was <50 % in 39 patients (50 % of the group), >50 % in 31 patients (40 %), and 100 % (intrathoracic stomach) in 7 (9.5 %). There was no need to convert to open surgery in this series, and the standard procedure was performed in all 75 patients. Gastropexy was necessary in two cases because of inability to reduce the stomach. The hiatus was reinforced with mesh strips in nine cases: A 360º PTFE mesh (GoreTex; W.L. Gore) was used in six patients (66 %) and a posterior buttressing polyethylene mesh in three (33 %).

Postoperative morbidity was found in three patients (4 %). One patient was reoperated on because of an inadvertent esophageal perforation, and two were reoperated on as a consequence of bleeding (mediastinal bleeding in one patient and short vessel bleeding in the other). The patient with esophageal perforation died because of sepsis (1.2 %).

The follow-up in March 2011 revealed that 7 of the 77 patients had died from causes unrelated to PEH, and 2 had a mental status that precluded them from answering the questionnaire and undergoing the radiologic examination. Another 2 patients refused to answer the questionnaire, and 11 could not be located. The study group was therefore made up of 55 patients (55/77, 72 % of the original group). The mean follow-up was 108 months (range 48–160 months) (Fig. 1).

At the follow-up interview, 43 of 55 patients (78 %) claimed that they were asymptomatic. The other 12 patients (22 %) reported symptoms of digestive origin that included episodes of dysphagia (n = 7), heartburn (n = 3), belching (n = 1), and chest pain (n = 1). Overall, seven patients were still in treatment with proton pump inhibitors (13 %).

Esophagography was performed in 43 of 55 patients (78 %), and recurrence was documented in 20 of the 43 (46 %). All recurrences were small sliding hernias (<3 cm long). No recurrent PEHs were found.

Among the 55 patients, 37 (67 %) answered the GIQLI questionnaire. The mean age at the time of the survey was 69 years (range 34–85 years). The mean GIQLI score was 111 (range 59–137; normal 147). Patients with objectively documented anatomic recurrence had a QoL index of 110 (range 89–132) compared to an index of 122 in the nonrecurrent hernia group (range 77–138, p < 0.01). There were no differences between the clinically, radiologically, or combined clinically and radiologically identified recurrent groups (Fig. 1; Tables 1, 2, 3).

A mesh was placed for buttressing the esophageal hiatus in 9 of 55 patients (18 %)—8 women and 1 man–whose mean age was 65 years (range 47–75 years). Clinical indications for mesh placement were the presence of gastric volvulus in four patients and intrathoracic stomach in two. All of the other patients had large PEHs with >50 % of intrathoracic stomach. One of the nine patients died during the postoperative follow-up, and five of the remaining eight patients (62 %) had mesh-related dysphagia symptoms—all of them after placement of a 360º GoreTex mesh. Three patients required reoperation because of mesh-related complications. In two patients, a fragment of the mesh that was causing fibrosis and dysphagia was removed, and a third patient required formal gastrectomy because the mesh had eroded into the esophagus. Two additional patients who developed stenosis required esophageal dilatation. Esophagography performed in eight cases revealed a radiologic recurrence in four patients (50 %)—all after a 360º GoreTex mesh placement. After a mean follow-up of 91 months (range 55–108 months), the GIQLI survey showed similar scores in patients with (126, range 134–119) and without (111, range 133–186) hernia recurrence (p = NS).

Discussion

The laparoscopic approach continues to be the standard technique for large PEHs. It offers a reasonable short-term outcome and long-term control of symptoms despite a recurrence rate that is higher than expected as compared with fundoplication for GERD or type I sliding hernias (Table 4) [3–12].

In this study we determined the subjective (QoL) and objective (radiologic) results after a mean follow-up of 108 months (range 48–160 months). Our findings confirm the safety of the laparoscopic approach in view of the good clinical outcomes but also emphasize the difficulty of achieving long-term anatomic repair.

Several points should be highlighted. The first is the difficulty of obtaining adequate information and follow-up regarding the outcome of the surgical procedure. This is mainly due to the advanced age of patients with PEH. From the potentially available 77 cases, 11 were unable to answer the questionnaire or had died. PEH is mainly seen in the elderly. The mean age of our patients available for the interview was 71 years, and the mean age of patients who died during follow-up was 84 years.

A second topic of interest is that our study provides valuable information regarding the long-term outcome of this restorative intervention. Such data are scarce to date. The only previously published study is that of Dallemagne et al. [6], who reported the outcome after a mean follow-up of 118 months (range 17–177 months) in a series of 85 patients. Their study also highlights the difficulty of achieving an objective follow-up in these patients, as information was available in only 64 (75 %) of 85 patients.

The main strength of our study is that it confirms two clinical features related to long-term outcome. The first is the fragility of conventional laparoscopic repair, related to an anatomic recurrence rate of up to 50 %. The profile of such a recurrence, however, should be carefully appraised. In our series, all the recurrences were small sliding hernias <3 cm in length, whereas there were no cases of large recurrent PEHs. Another aspect of the recurrence is that it develops over time. In an initial study that included 46 patients, we found a recurrence rate of 21 % at 50 months (mean follow-up 24 months) compared to 50 % at 96 months [4].

The second important aspect is the clinical impact of the repair itself. Only 17 % of the patients reported digestive symptoms. When we measured the long-term QoL after the laparoscopic hernia repair, we observed QoL scores that were similar to those obtained in our initial midterm study. However, patients with radiologic evidence of failure or recurrent symptoms had an small but significant reduction in the QoL scores compared to patients without recurrence.

These two findings emphasize that even though the final anatomic result might not be perfect the clinical impact of recurrence is low. They also indicate that laparoscopic repair is clinically efficacious [14].

The most frequent method for preventing hiatal hernia recurrence is reinforcement with mesh, but the use of mesh continues to be a controversial issue [15]. Several authors have observed advantages with the use of mesh in terms of recurrence prevention [15, 16]. Others, however, have reported potentially severe complications [17]. The long-term outcome after a mean follow-up of 78 months in a prospective randomized trial using biologic mesh (small intestinal submucosa) as a buttress material have shown a similar recurrence rate (54 vs. 59 %) with or without the use of mesh [18]. In our experience, results after selective use of mesh were poorer than those observed by other authors. In our institution, placement of 360º PTFe mesh resulted in a 50 % recurrence rate and, more importantly, in the need to reoperate because of stenosis or mesh migration and subsequent gastric resection. These findings stress the need to consider carefully the use of mesh in each individual case. When it is needed, we recommend a low-weight nonreabsorbable polyglactin/polyvinyl mesh placed over the closure of the crura as a buttress.

Conclusions

Our results from this 13-year follow-up study show that laparoscopic PEH repair is clinically efficacious but is associated with up to 50 % incidence of small anatomic recurrences. Further studies are needed to clarify the anatomic, pathologic, and physiologic, factors that impair adequate outcomes and to tailor the approach to the patient. In the meantime, it seems clear that conventional laparoscopic repair is satisfactory for most patients even though a residual small sliding hernia may remain over time.

References

Schieman C, Grondin SC (2009) Paraesophageal hernia: clinical presentation, evaluation, and management controversies. Thorac Surg Clin 19:473–478

Nason KS, Luketich JD, Witteman BP et al (2012) The laparoscopic approach to paraesophageal hernia repair. J Gastrointest Surg 16:417–426

Hashemi M, Peters JH, DeMeester TR et al (2000) Laparoscopic repair of large type III hiatal hernia: objective followup reveals high recurrence rate. J Am Coll Surg 190:553–560

Targarona EM, Novell J, Vela S et al (2004) Mid term analysis of safety and quality of life after the laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hiatal hernia. Surg Endosc 18:1045–1050

Furnee EJ, Draaisma WA, Simmermacher RK et al (2010) Long-term symptomatic outcome and radiologic assessment of laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair. Am J Surg 199:695–701

Dallemagne B, Kohnen L, Perretta S et al (2011) Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia: long-term follow-up reveals good clinical outcome despite high radiological recurrence rate. Ann Surg 253:291–296

Luketich JD, Nason KS, Christie NA et al (2010) Outcomes after a decade of laparoscopic giant paraesophageal hernia repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 139:395–404

Braghetto I, Korn O, Csendes A et al (2010) Postoperative results after laparoscopic approach for treatment of large hiatal hernias: is mesh always needed? Is the addition of an antireflux procedure necessary? Int Surg 95:80–87

Zaninotto G, Portale G, Costantini M et al (2007) Objective follow-up after laparoscopic repair of large type III hiatal hernia: assessment of safety and durability. World J Surg 31:2177–2183. doi:10.1007/s00268-007-9212-2

Mittal SK, Bikhchandani J, Gurney O et al (2011) Outcomes after repair of the intrathoracic stomach: objective follow-up of up to 5 years. Surg Endosc 25:556–566

Louie BE, Blitz M, Farivar AS et al (2011) Repair of symptomatic giant paraesophageal hernias in elderly (>70 years) patients results in improved quality of life. J Gastrointest Surg 15:389–396

Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S et al (1995) Gastrointestinal quality of life index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg 82:216–222

Quintana JM, Cabriada J, López de Tejada I et al (2001) Translation and validation of the gastrointestinal quality of life index (GIQLI). Rev Esp Enferm Dig 93:693–706

Oelschlager BK, Petersen RP, Brunt LM et al (2012) Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: defining long-term clinical and anatomic outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg 16:453

Targarona EM, Bendahan G, Balague C et al (2004) Mesh in the hiatus: a controversial issue. Arch Surg 139:1286–1296

Herbella FA, Patti MG (2011) Hiatal mesh repair: current status. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 21:61–66

Stadlhuber RJ, Sherif AE, Mittal SK et al (2009) Mesh complications after prosthetic reinforcement of hiatal closure: a 28-case series. Surg Endosc 23:1219–1226

Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA, Hunter JG et al (2011) Biologic prosthesis to prevent recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: long term follow up from a prospective randomized trial. J Am Coll Surg 213:461–468

Conflict of interest

Drs. Eduardo M. Targarona, Samuel Grisales, Ozlem Uyanik, Carmen Balague, Juan Carlos Pernas, and Manuel Trias, have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Targarona, E.M., Grisales, S., Uyanik, O. et al. Long-Term Outcome and Quality of Life After Laparoscopic Treatment of Large Paraesophageal Hernia. World J Surg 37, 1878–1882 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2047-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-2047-0