Abstract

Background

Fatal trauma is one of the leading causes of death in Western industrialized countries. The aim of the present study was to determine the preventability of traumatic deaths, analyze the medical measures related to preventable deaths, detect management failures, and reveal specific injury patterns in order to avoid traumatic deaths in Berlin.

Materials and methods

In this prospective observational study all autopsied, direct trauma fatalities in Berlin in 2010 were included with systematic data acquisition, including police files, medical records, death certificates, and autopsy records. An interdisciplinary expert board judged the preventability of traumatic death according to the classification of non-preventable (NP), potentially preventable (PP), and definitively preventable (DP) fatalities.

Results

Of the fatalities recorded, 84.9 % (n = 224) were classified as NP, 9.8 % (n = 26) as PP, and 5.3 % (n = 14) as DP. The incidence of severe traumatic brain injury (sTBI) was significantly lower in PP/DP than in NP, and the incidence of fatal exsanguinations was significantly higher. Most PP and NP deaths occurred in the prehospital setting. Notably, no PP or DP was recorded for fatalities treated by a HEMS crew. Causes of DP deaths consisted of tension pneumothorax, unrecognized trauma, exsanguinations, asphyxia, and occult bleeding with a false negative computed tomography scan.

Conclusions

The trauma mortality in Berlin, compared to worldwide published data, is low. Nevertheless, 15.2 % (n = 40) of traumatic deaths were classified as preventable. Compulsory training in trauma management might further reduce trauma-related mortality. The main focus should remain on prevention programs, as the majority of the fatalities occurred as a result of non-survivable injuries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Trauma is still the leading cause of death among people ≤44 years of age, and it represents the third most common cause of death for all ages in the industrialized world [1]. Additionally, trauma is postulated by the World Health Organization to be the leading cause of losing years of life worldwide by 2020. Zollinger et al. stated in 1955 that traffic injuries are major surgical problems, prompting German trauma surgeons to initiate the establishment of trauma systems in which specially trained emergency physicians are deployed at the scene of the injury in an attempt to provide a higher level of emergency care before the patient’s arrival at the hospital [2–6]. Continuous advances and innovations in pre-hospital and in-hospital critical care and surgical trauma management combine with the above-mentioned philosophy to “bring the hospital to the trauma patient.” This has significantly lowered trauma mortality in Germany and has made the German rescue system famous throughout the world [4, 7]. Despite the socioeconomic importance of successful trauma treatment and prevention programs, no systematic analysis of prehospital traumatic deaths had been performed in Germany until 2010.

In that study we investigated primarily all trauma deaths in the German capital of Berlin, examining the prehospital setting and the intensive care unit (ICU) as the two major “hotspots” of trauma management. In our study 59 % of the fatalities occurred before admission to a hospital and 33 % occurred in the ICU [8].

That nearly two-thirds of all traumatic deaths occurred in the prehospital setting, highlights the value of prehospital emergency medicine and trauma prevention programs to reduce traumatic deaths in the future [8, 9]. A Norwegian study in 2011 demonstrated that over 70 % of all trauma victims in rural areas died prior to the arrival of medical personnel, underscoring the need for trauma prevention [10].

A recent study of our working group indicates a change from the “golden hour of trauma” concept to a more injury-adapted prehospital management of trauma patients with the necessity of invasive, time-consuming prehospital measures, e.g., intubation in sTBI and chest decompression in (tension) pneumothorax [4].

We aimed to determine the preventability of traumatic deaths, analyze the medical measures related to preventable deaths, detect management failures, and reveal specific injury patterns to avoid traumatic deaths in Berlin. Furthermore, we compare the Berlin data of traumatic death with already published international data. To our knowledge this is the first German study since the hallmark publication of Wagoner et al. [11] in 1961 dealing with the topic of preventability of traumatic deaths.

Materials and methods

We performed a prospective observational study investigating all trauma-related deaths in Berlin from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2010. Because of the epidemiologic and descriptive nature of this study no ethics committee approval was required.

The German capital, Berlin, sustains 3.4 million inhabitants in an urban area of 892 km2 (http://www.berlin.de) and is served by 39 hospitals with emergency departments; five of these can be classified as level I trauma centers. Emergency medical service is provided by the Berlin fire department with 38 fire stations, 40 ambulance stations housing 101 ambulances, 18 emergency physician staffed ambulances [12], and 2 rescue helicopters on call 24 h a day. The central dispatch center is activated by calling 112 (http://www.berliner-feuerwehr.de). Emergency physicians in Germany are physicians with at least 2 years of clinical practice (6 months ICU, 6 months Emergency Department [ED], 1 year ward) in different specializations (internal medicine, surgery, general medicine, anesthesiology), who obtained theoretical and practical training in emergency medicine through special courses. Helicopter emergency medical services emergency physicians are usually more experienced and must have graduated in their specialization. All severely injured patients without certain signs of death were seen or treated by an emergency physician before being transported to the hospital, or, in case of death, to a morgue. German law requires that every death must be classified by a physician as either “natural,” “unnatural,” or “unclear” as soon as possible. “Unnatural” or “unclear” cases of death must be reported to the police and, subsequently, to the public prosecutor, who initiates further police investigation and orders an autopsy, depending on the individual circumstances of each case. Thus, all traumatic deaths listed in terms of an “unnatural manner of death” are recorded by the public prosecutor’s office with subsequent police investigation files, or at least a death certificate.

Inclusion criteria were all deaths following trauma from 1 January to 31 December in 2010 in Berlin with or without subsequent autopsy ordered by the public prosecutor’s office (n = 440). Fatalities from strangulation, burns, drowning, and death following pre-existing illnesses or complications not primarily associated with trauma (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart attack) and trauma casualties without autopsy were excluded.

Data were acquired via the public prosecutor’s office of Berlin where complete police investigation files, including medical records, death certificates, and autopsy protocols were accessible. Medical records, death certificates with date and time of death, and autopsy protocols were evaluated. Medical diagnoses were annotated based on medical records and death certificates, and autopsy diagnoses were annotated based on autopsy reports. Demographic data including age, gender, trauma mechanism (blunt, penetrating, or both), survival time, and cause of death were recorded.

Preventability of traumatic deaths

To determine the preventability of traumatic deaths, only casualties undergoing autopsy (n = 264) were considered for analysis of anonymized data by an interdisciplinary expert board (trauma surgeons, forensic pathologist, and emergency physician). Assessment was made as to the preventability of traumatic death and also to the appropriateness of medical measures with regard to the injury pattern.

Preventability of death was judged based on the following three criteria, according to the recommendations of MacKenzie et al. and Shackford et al. [13, 14]:

Non-preventable (NP)

Anatomical organ/tissue destruction non-survivable under perfect circumstances and perfect resuscitation.

Potentially preventable (PP)

Severe anatomical injuries potentially survivable under perfect circumstances and perfect resuscitation and/or conscious patients with the ability to act at the scene and/or patients with signs of life at the scene and absence of anatomical non-survivable injuries.

Definitely preventable (DP)

Moderate anatomical injuries (pathological classified organ injury according to the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) classification with Abbreviated Injury Severity Score (AIS) ≤3) with revisable live threat (e.g., isolated tension pneumothorax, severe external bleeding, non-fatal sTBI-induced upper airway obstruction).

The criteria of NP, PP, and DP, together with an anonymized case presentation of all 264 casualties, were presented to the expert board via the structured Delphi-method. In the first round every expert had to judge independently the preventability of death for the presented cases. Agreements were achieved in 88 % after the first round. For the remaining 12 % (n = 31) the experts had to explain their decision. In the second round the explanations were sent to all members of the committee and the experts were asked to re-judge the remaining 31 cases based on the explanations. After the second round, agreement for all cases was achieved.

Statistical analysis was performed with PASW 20.0. The median and interquartile range (IQR) for age and number of prehospital measures were calculated. For descriptive statistical evaluation, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test for independent group comparison was used; p values < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of trauma casualties

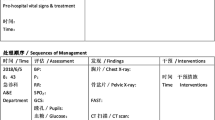

From 1 January to 31 December, 440 trauma casualties were recorded. In 60 % of death cases an autopsy was performed (n = 264). Table 1 presents the characteristics of trauma casualties with and without autopsy.

Fatalities with subsequent autopsy (A+) were significantly younger (p = 0.001) and male (p = 0.003) when compared to victims without autopsy [15]. The incidence of traumatic cardiopulmonary resuscitation (tCPR) (p = 0.03), penetrating trauma (p = 0.001) and fatal exsanguination was significantly higher in A+. More casualties of A+ group died in the prehospital setting when compared to A− (p = 0.001). No statistically significant differences were detected for the cause of traumatic deaths in both groups. The following analysis is exclusively based on trauma fatalities with subsequent autopsy (A+).

Trauma mechanisms

In 30.7 % the trauma mechanism was a fall from a height >3 meters, 19.3 % falls from a standing height, 18.2 % traffic accident, 17.8 % crime-associated injury (shot, stabbed), and 9.1 % struck by a train. Records indicate that 29.9 % (n = 79) of the casualties were transported to the hospital; in 17.7 % (n = 14), by rescue helicopter. Another 13.9 % were able to act at the accident site, with a mean survival time of 18.4 h. Severe traumatic brain injury (sTBI) occurred in 67.8 % of all casualties, whereas isolated sTBI was detected in 29.5 % of cases. Thoracic injuries were seen in 35.2 % of all casualties, with 1.9 % isolated pneumothorax, 12.1 % hemothorax, and 21.2 % combined pneumo-hemothorax. The majority of fatalities suffered from blunt trauma mechanisms (72.7 %). The minority of penetrating trauma predominantly involved the chest (34.7 %; n = 25). In 60 % (n = 15) of penetrating chest injuries, an isolated cardiac injury occurred in 9 cases and was combined in 6 patients with thoracic vascular injuries. Tracheobronchial injury was observed only in 10 % (n = 27) of all fatalities. In 41 % (n = 11) it was associated with penetrating trauma.

Preventability of traumatic deaths

Some 84.9 % (n = 224) of fatalities were judged as non-preventable (NP) and 15.2 % (n = 40) as potentially (PP) or definitely preventable (DP). In 9.8 % (n = 26) PP and 5.3 % (n = 14) DP was observed (Fig. 1).

Localization of the scene of traumatic deaths

The localization of traumatic deaths and their distribution relating to their preventability is shown in Fig. 2. The localization of traumatic death is not automatically equal to the origin of management failures—e.g., patient died in ER with prehospital management failure (trauma management failures).

Some 69.7 % of NP deaths occurred in the prehospital setting, followed by 24.1 % in the intensive care unit (ICU). In addition, 92.4 % of all PP casualties died before admission to a hospital, 3.8 % in the operating room (OR) and in the ICU, respectively. Definitely preventable deaths occurred predominantly in the prehospital setting and ICU (35.7 %), followed by the emergency department (ED, 14.4 %), and 7.1 % in the OR and on the ward.

Potentially preventable deaths

Twenty-six trauma victims fulfilled the criteria of potentially preventable deaths. In 73.1 % of all potentially preventable deaths exsanguination was the cause of death, followed by 11.5 % with thoracic trauma.

In 84.6 % (n = 22) of patients with unwitnessed trauma, delayed resuscitation was the reason for a potentially preventable death. Of these, 57.7 % (n = 15) were suicides with simple external bleeding due to sharp force injury. Four casualties died from simple soft tissue lacerations or open fracture, combined with anticoagulant therapy (phenprocoumon) after a fall from a standing height. In 15.4 % (n = 4) of cases prehospital thoracotomy (2 pericardial tamponade, 2 hemothorax) might have saved their lives.

Definitely preventable deaths

Fourteen casualties were judged as definitely preventable traumatic deaths. In total, 57.1 % of DP cases died from exsanguination, followed by polytrauma in 21.4 % of cases (definition [8]).

Trauma management failures

Prehospital trauma management failure

In four fatalities the cause of death was isolated tension pneumothorax due to non- (n = 3) or insufficient (n = 1) chest decompression in the prehospital setting after penetrating chest trauma. In four fatalities underlying trauma as the cause of the emergency call was not recognized by the emergency service personnel, and therefore, no trauma therapy was performed. Three patients had unstable pelvic fractures, and one victim was found unconscious after a fall from a height >3 meters, but was considered to have suffered a myocardial infarction with subsequent cardiac arrest. Thus, no trauma-related therapy was performed. Two patients bled to death from stab wounds to the external femoral artery; no or insufficient external bleeding control measures—e.g., local pressure, tourniquet, or arterial clamp—were carried out. In one case there was insufficient bleeding control, and in the one case the bleeding source went unrecognized. One patient trapped in his car after an accident died from asphyxia because upper airway management was not maintained in the prehospital situation even though there was access to the thorax and skull. An alternative airway tool like a combitube or a laryngeal tube was not inserted, nor was a surgical airway established.

Clinical trauma management failure

Three trauma victims were initially admitted to the ER, and then transferred to hospital wards. In these three cases there was a missed or delayed diagnosis of bleeding. All patients received full-body computed tomography (CT) scans without identification of contrast extravasation. The bleeding sources were unrecognized and included an untreated pelvic fracture (n = 1), rib fractures (n = 1), and abdominal injury (n = 1). In two cases there was a history of anticoagulant therapy. Surgical bleeding control was attempted in only one case.

Preventable deaths and sTBI

Knowing that sTBI is basically influencing survival after trauma, a sub-analysis for the preventability of traumatic deaths with (sTBI+; n = 179) and without sTBI (sTBI−; n = 85) and isolated sTBI (isTBI+; n = 78, is TBI−; n = 186) was performed.

That test showed that 96.1 % (n = 172) of sTBI+ were NP, 2.2 % were PP (n = 4), and 1.7 % were DP (n = 3) compared to 25.9 % PP (n = 22) and 12.9 % (n = 11) DP in the sTBI− group. For the isolated sTBI+ 96.2 % of traumatic deaths were NP with 3.8 % (n = 3) PP deaths and no DP deaths.

The incidence of PP or DP traumatic deaths was significantly lower in the group with sTBI (p = 0.001) and isolated sTBI (p = 0.03; 0.01).

Preventable deaths and penetrating trauma

In this series,174 fatalities suffered from blunt trauma and 72 suffered from penetrating trauma mechanisms. In the penetrating trauma group, there were significantly (p = 0.001) more PP (25 %; n = 18) and DP (5.6 %; n = 4) deaths as compared to blunt trauma (4.2 %; n = 8/5.2 %; n = 10).

Preventable deaths and prehospital measures

In total, any type of advanced prehospital measure (intravenous access, endotracheal intubation, application of chest drains, cardiopulmonary resuscitation) was performed in 41.3 % (n = 109) of all trauma fatalities, with a median of 2 and an IQR of 1 prehospital invasive measure.

In the DP death group significantly more frequent invasive prehospital measures were performed when compared to the NP death group (71.4 versus 42.9 %; p = 0.02). The incidence of specific invasive prehospital measures in the NP, PP, and DP groups are given in Table 2.

The highest incidence of traumatic cardiopulmonary resuscitation (tCPR) was seen in the DP group (35.7 %), as compared to the PP group (11.5 %) and the NP group (27.7). In all three groups a high rate of intravenous (i.v.) access and endotracheal intubation in PP and DP group was found. Notably, despite a high rate of CPR after (recognized) traumatic cardiac arrest, no chest drain or other chest decompression measures were performed in the DP group.

Preventable deaths and rescue helicopter

Some 29.9 % (n = 79) of all fatalities reached the hospital alive. In 17.7 % (n = 14) of cases the HEMS crew, consisting of a pilot, an emergency physician, and a paramedic with special qualifications, treated the patients and transported them to a hospital [16]. In 82.3 % of cases, treatment and transport were carried out by NAW (“Notarztwagen”: an ambulance staffed by an emergency physician and a paramedic). The HEMS crew performed significantly more invasive prehospital measures (median 2, IQR 0.25; p = 0.04) than the NAW crew (median 2, IQR 1), especially for the incidence of endotracheal intubation (HEMS 100 % versus NAW 71.9 %; p = 0.03) and chest drain (HEMS 21.4 % versus NAW 3.5 %; p = 0.02). The rate of tCPR was higher in the HEMS group (35.7 %) when compared to NAW group (18.5 %), but without statistical significance (p = 0.1). Furthermore, no PP or NP deaths were recorded for the HEMS crew (Table 3).

Discussion

We present for the first time a systematic analysis of potentially and definitely preventable traumatic deaths in Berlin, Germany. Data analysis evaluating PP and DP deaths are based only on fatalities referred for autopsy (group A+). Notably, there are significant differences between groups A± (Table 1). Based on the results of our epidemiologic study for traumatic deaths in Berlin that revealed the prehospital setting as the “major problem” of trauma management, we focused especially on prehospital PP and DP traumatic deaths [8]. Therefore, group A+, with 70 % of prehospital deaths was appropriate compared to group A− with an incidence of 42 % to analyse especially prehospital traumatic deaths.

Exsanguination as the leading potentially preventable cause of death was nearly threefold higher in group A+. In contrast to prehospital deaths, in only 30 % of clinical traumatic deaths was an autopsy performed, this being considered as a gold standard quality measure. Therefore, the number of potentially or definitely preventable clinical deaths is underrepresented when compared to prehospital deaths, and there might be a high number of unreported DP clinical deaths. Older people are rarely autopsied and specific complications from co-morbidities like anticoagulant therapy, i.e., iatrogenic coagulopathy, and secondary exsanguination might be underrepresented in our study. Therefore, to improve clinical and prehospital trauma management and regularly evaluate it in morbidity-mortality conferences, we recommend the routine use of autopsy in trauma patients, with the simultaneous close cooperation of forensic scientists, trauma surgeons, anesthetists, prehospital personnel, and all other specialties involved in trauma [17]. The autopsy rate of 60 % appears low, but it is outstandingly high when compared to average autopsy rates of 2–5 % of all deaths in Germany. Nevertheless, some differences between our group A+ and a total Berlin-wide collective or even a German population must be considered for the interpretation of our results.

In our study group, we considered 15.2 % (n = 40) of the investigated trauma fatalities as PP or DP. Comparing this number to the literature since 1953 with a mean preventability of 21.7 % regardless of the year of investigation, infrastructural differences, socioeconomic background, or differences in rescue system (emergency physician, paramedic), our results appear quite acceptable [18–27]. Going into detail and focusing on publications of the twenty-first century from the industrialized world, rates of traumatic death preventability from 4.5 to 6.7 % were published, revealing the potential of trauma management in Berlin in the future [28, 29].

Confirming previous studies, victims without sTBI had up to a tenfold higher incidence of DP/PP and consequently a higher potential of preventable death than sTBI-trauma patients [30]. In summary, trauma victims without sTBI have a greater possibility for trauma management improvement, although it is possible that other simple (bleeding control) or invasive measures (chest drain) might be underrepresented when compared to i.v. access or intubation. This hypothesis is proven by the finding that there were no cases of PP or DP traumatic death in casualties treated by rescue helicopter crew in Germany, known to be well equipped and trained [31].

More than 90 % of the PP deaths and one-third of the DP deaths occurred in the prehospital setting. This result stands in contrast to previous publications stating that most of the inappropriate care happens in the emergency department [29, 32, 33]. Our belief is that this discrepancy reflects the different rescue systems. In Germany the emergency medicine philosophy is “to bring the resuscitation room to the patient,” and emergency physicians begin to invasively treat trauma patients at the site of the traumatic incident. Nevertheless, most of the studies dealing with the topic of preventability of traumatic deaths have neglected the prehospital situation, focusing on in-hospital treatment. Additionally, the level of experience and training in trauma management, in our opinion, is crucial for the effective and appropriate management of prehospital trauma patients. For example, in our study no potentially or definitely preventable traumatic deaths occurred in the group treated by HEMS crew. Usually the experience and grade of qualification of HEMS emergency physicians is higher than those on NAW. Despite the fact that trauma emergencies are seldom missions in Germany, the incidence of trauma emergency calls on a rescue helicopter is much higher than on NAW, indicating a higher level of experience and routine in management of trauma patients. Thus it is clear that we need nationwide experienced and well-equipped rescue teams for our trauma patients, e.g., specialized trauma rescue helicopters or trauma NAW.

The effectiveness of the Berlin rescue system and prevention program is accepted and reflected by the very low trauma mortality (13/100,000 inhabitants) for 2010 in Berlin [7, 8, 34]. Nevertheless, 5.3 % of traumatic deaths were definitely preventable. According to our expert board, 14 lives could have been saved. Assuming that our collective is roughly representative for Germany (80 million inhabitants), it might be possible to save more than 297 lives annually.

Furthermore, we detected a statistically significant association between the cause of death “exsanguination” and the preventability of death for PP and DP. Analogous to other publications, hemorrhage was the most frequent cause of DP or PP deaths, supported by the fact that hemorrhage control is known to be the major management error in hospitals [29]. Furthermore, the detailed analysis of our PP deaths highlights the issue of unwitnessed trauma incidents—in our collective, unmated elderly people suffered from minor injuries leading to death from exsanguination. Another known reversible cause of traumatic cardiac arrest is pericardial tamponade; four casualties in Berlin 2010 might have benefitted from comprehensive resuscitation with performance of an emergency thoracotomy even in the prehospital setting [35]. The practicability, economy, and efficiency of introducing emergency thoracotomy in the prehospital situation with an incidence of four cases per year in an urban area seem hard to justify, given the lack of supporting data. In contrast to that, a high potential for saving lives was pointed out by analysis of DP and PP deaths by simple and practical prehospital measures, e.g., sufficient bleeding control by tourniquets, arterial clamps, or insertion of a Foley catheter into a stab wound. Four patients might have been saved by decompression of their tension pneumothorax. A systematic body check to detect unstable thoracic or pelvic injuries and therefore recognize the underlying trauma might also have saved the lives of 4 patients. The lack of absolute basics in trauma management, like clinical examination and disregard of the ABC-rule should be politically changed by making ATLS (Advanced Trauma Life Support), PHTLS (prehospital Trauma Life Support), ITLS (international Trauma Life Support), or Trauma-Management compulsory for all medical personal involved in pre-/clinical trauma management in Germany. Furthermore, mortality-morbidity conferences for prehospital and clinical personnel should be established and should take place on a regular basis, at least four times a year.

Besides the prehospital setting, the major clinical problems were unrecognized/occult bleeding in patients with initial false negative contrast CT scans (no contrast extravasation), and patients with iatrogenic coagulopathy who died from exsanguinations in the ward.

Conclusions

The trauma mortality in Berlin, compared to worldwide published data, is low. Nevertheless, 15.2 % (n = 40) of traumatic deaths were classified as preventable. Most of the management failures occurred in the prehospital setting, with none of these fatalities treated by rescue helicopter teams. Therefore, compulsory training in trauma management might further reduce the trauma mortality. Close cooperation between forensic pathologists and trauma surgeons can be effective in improving trauma management in the future. The main focus should, however, remain on prevention programs, since the majority of fatalities occurred from primarily non-preventable injuries.

Abbreviations

- A+:

-

Autopsy performed

- A−:

-

No autopsy performed

- AAST:

-

American Association for the Surgery of Trauma

- AIS:

-

Abbreviated injury severity score

- CPR:

-

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- CT:

-

Computer tomography

- DP:

-

Definitely preventable death

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- EMT:

-

Emergency medical technician

- HEMS:

-

Helicopter emergency medical service

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- i.v.:

-

Intra-Venous

- NAW:

-

Emergency physician and paramedic staffed ambulance

- NP:

-

Non-Preventable death

- OR:

-

Operation room

- PP:

-

Preventable death

- sTBI:

-

Severe traumatic brain injury

- tCPR:

-

Traumatic cardio-pulmonary resuscitation

References

Pfeifer R, Tarkin IS, Rocos B et al (2009) Patterns of mortality and causes of death in polytrauma patients—has anything changed? Injury 40:907–911

Ottosson A, Krantz P (1984) Traffic fatalities in a system with decentralized trauma care. A study with special reference to potentially salvageable casualties. JAMA 251:2668–2671

Zollinger RW (1955) Traffic injuries; a surgical problem. AMA Arch Surg 70:694–700

Kleber C, Lefering R, Kleber AJ et al (2012) Rettungszeit und Überleben von Schwerverletzten in Deutschland. Unfallchirurg. doi:10.1007/s00113-011-2132-5

Arnold JL (1999) International emergency medicine and the recent development of emergency medicine worldwide. Ann Emerg Med 33:97–103

Dick WF (2003) Anglo-American vs. Franco-German emergency medical services system. Prehosp disaster med 18:29–35 discussion 35–27

Probst C, Pape HC, Hildebrand F et al (2009) 30 years of polytrauma care: an analysis of the change in strategies and results of 4849 cases treated at a single institution. Injury 40:77–83

Kleber C, Giesecke MT, Tsokos M et al (2012) Overall distribution of trauma-related deaths in Berlin 2010: advancement or stagnation of German trauma management? World J Surg 36:2125–2130. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1650-9

Mock C, Quansah R, Krishnan R et al (2004) Strengthening the prevention and care of injuries worldwide. Lancet 363(9427):2172–2179

Bakke HK, Wisborg T (2011) Rural high north: a high rate of fatal injury and prehospital death. World J Surg 35:1615–1620. doi:10.1007/s00268-011-1102-y

Van Wagoner FH (1961) A three year study of deaths following trauma. J Trauma 1:401–408

Chen XP, Losman JA, Cowan S et al (2002) Pim serine/threonine kinases regulate the stability of Socs-1 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:2175–2180

MacKenzie EJ, Steinwachs DM, Bone LR et al (1992) Inter-rater reliability of preventable death judgments. The Preventable Death Study Group. J Trauma 33:292–302 discussion 302–303

Shackford SR, Hollingsworth-Fridlund P, McArdle M et al (1987) Assuring quality in a trauma system—the Medical Audit Committee: composition, cost, and results. J Trauma 27:866–875

Mock CN, Jurkovich GJ, nii-Amon-Kotei D et al (1998) Trauma mortality patterns in three nations at different economic levels: implications for global trauma system development. J Trauma 44(5):804–812 discussion 812–814

Roy MS, Gosselin J, Hanna N et al (2004) Influence of the state of alertness on the pattern visual evoked potentials (PVEP) in very young infant. Brain Dev 26:197–202

Buschmann CT, Gahr P, Tsokos M et al (2010) Clinical diagnosis versus autopsy findings in polytrauma fatalities. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 18:55

Jat AA, Khan MR, Zafar H et al (2004) Peer review audit of trauma deaths in a developing country. Asian J Surg 27:58–64

Limb D, McGowan A, Fairfield JE et al (1996) Prehospital deaths in the Yorkshire Health Region. J Accid Emerg Med 13:248–250

Papadopoulos IN, Bukis D, Karalas E et al (1996) Preventable prehospital trauma deaths in a Hellenic urban health region: an audit of prehospital trauma care. J Trauma 41:864–869

West JG, Trunkey DD, Lim RC (1979) Systems of trauma care. A study of two counties. Arch Surg 114:455–460

Draaisma JM, de Haan AF, Goris RJ (1989) Preventable trauma deaths in The Netherlands—a prospective multicenter study. J Trauma 29:1552–1557

Stocchetti N, Pagliarini G, Gennari M et al (1994) Trauma care in Italy: evidence of in-hospital preventable deaths. J Trauma 36:401–405

Shackford SR, Hollingworth-Fridlund P, Cooper GF et al (1986) The effect of regionalization upon the quality of trauma care as assessed by concurrent audit before and after institution of a trauma system: a preliminary report. J Trauma 26:812–820

McDermott FT, Cooper GJ, Hogan PL et al (2005) Evaluation of the prehospital management of road traffic fatalities in Victoria, Australia. Prehosp Disaster Med 20:219–227

McDermott FT, Cordner SM, Tremayne AB (1996) Evaluation of the medical management and preventability of death in 137 road traffic fatalities in Victoria, Australia: an overview. Consultative Committee on Road Traffic Fatalities in Victoria. J Trauma 40:520–533 discussion 533–525

Davis JW, Hoyt DB, McArdle MS et al (1992) An analysis of errors causing morbidity and mortality in a trauma system: a guide for quality improvement. J Trauma 32:660–665 discussion 665–666

Ashour A, Cameron P, Bernard S et al (2007) Could bystander first-aid prevent trauma deaths at the scene of injury? Emerg Med Australas 19:163–168

Sanddal TL, Esposito TJ, Whitney JR et al (2011) Analysis of preventable trauma deaths and opportunities for trauma care improvement in Utah. J Trauma 70:970–977

Anderson ID, Woodford M, de Dombal FT et al (1988) Retrospective study of 1,000 deaths from injury in England and Wales. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 296(6632):1305–1308

Frink M, Probst C, Hildebrand F et al (2007) The influence of transportation mode on mortality in polytraumatized patients. An analysis based on the German Trauma Registry. Unfallchirurg 110:334–340

Esposito TJ, Sanddal ND, Hansen JD et al (1995) Analysis of preventable trauma deaths and inappropriate trauma care in a rural state. J Trauma 39:955–962

Maio RF, Burney RE, Gregor MA et al (1996) A study of preventable trauma mortality in rural Michigan. J Trauma 41:83–90

Haas NP, Hoffmann RF, Mauch C et al (1995) The management of polytraumatized patients in Germany. Clin Orthop Relat Res 318:25–35

Davies GE, Lockey DJ (2011) Thirteen survivors of prehospital thoracotomy for penetrating trauma: a prehospital physician-performed resuscitation procedure that can yield good results. J Trauma 70:E75–E78

Acknowledgments

Contributions were made possible by DFG funding through the Berlin-Brandenburg School for Regenerative Therapies GSC 203. The authors are grateful to Dr. Paul Bedford for his contribution to the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kleber, C., Giesecke, M.T., Tsokos, M. et al. Trauma-related Preventable Deaths in Berlin 2010: Need to Change Prehospital Management Strategies and Trauma Management Education. World J Surg 37, 1154–1161 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-1964-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-1964-2