Abstract

Background

Ventral hernia repairs are one of the most common surgeries performed. Symptoms are the most common motivation for repair. Unfortunately, outcomes of repair are typically measured in recurrence and infection rather than patient focused results. We correlated factors associated with decreased patient satisfaction, chronic pain, and diminished functional status following laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (LVHR)

Methods

A retrospective study of 201 patients from two affiliated institutions was performed. Patient satisfaction, chronic abdominal pain, pain scores, and Activities Assessment Scale results were obtained in 122 patients. Results were compared with univariate and multivariate analysis.

Results

Thirty-two (25.4 %) patients were dissatisfied with their LVHR while 21 (17.2 %) patients had chronic abdominal pain and 32 (26.2 %) patients had poor functional status following LVHR. Decreased patient satisfaction was associated with perception of poor cosmetic outcome (OR 17.3), eventration (OR 10.2), and chronic pain (OR 1.4). Chronic abdominal pain following LVHR was associated with incisional hernia (OR 9.0), recurrence (OR 4.3), eventration (OR 6.0), mesh type (OR 1.9), or ethnicity (OR 0.10). Decreased functional status with LVHR was associated with mesh type used (OR 3.7), alcohol abuse (OR 3.4), chronic abdominal pain (OR 1.3), and age (OR 1.1).

Conclusions

One-fourth of patients have poor quality outcome following LVHR. These outcomes are affected by perception of cosmesis, eventration, chronic pain, hernia type, recurrence, mesh type, and patient characteristics/co-morbidities. Closing central defects and judicious mesh selection may improve patient satisfaction and function. Focus on patient-centered outcomes is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ventral hernia repairs are one of the most common procedures performed by general surgeons [1]. The main motivation for hernia repair revolves around symptoms such as pain, discomfort, and decreased ability to function normally [2–5]. While risk of incarceration and strangulation is also a concern, the likelihood of these complications is modest in comparison to physical symptoms [2–5]. For other types of hernias (such as inguinal or hiatal hernias), symptoms are the main reason for repair, and patients with few or no symptoms can consider conservative treatment or watchful waiting [6].

Despite the fact that quality of life is the main motivation for hernia repair, surgeons tend to measure success in terms of clinical outcomes such as surgical site infection, hernia recurrence, and seroma formation [7–22]. Quality of life measures, including patient satisfaction, chronic pain, and functional status, are seldom measured or reported [23–30]. The purposes of the present study were to evaluate patient satisfaction, chronic pain, and functional status following laparoscopic ventral hernia repair and to patient factors that affect quality of life.

Methods

The study was a retrospective cohort study of all patients (consecutive) who underwent a laparoscopic ventral hernia repair at a two affiliated hospitals from 2000 to 2010. All patients who completed a successful laparoscopic ventral hernia repair were included in the study. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at both participating institutions.

Patient demographics, co-morbidities, hernia data, operative data, radiographic data, and outcomes were abstracted from the electronic medical records. The attending surgeon was recorded as a variable for outcomes and was identified by number, Surgeon 1 through Surgeon 7. Our primary outcomes (i.e., patient satisfaction, chronic pain, and functional status) were obtained by clinical follow-up. Starting in 2010, we employed standardized patient follow-up for ventral hernia repairs to assess both standard outcomes and patient quality of life outcomes. For quality control and assessment, we contacted patients for clinical follow-up and examination. Local patients were encouraged to follow-up clinically for examination and assessment. For those who were not local or who were reluctant to return for a clinic visit, a telephone interview was substituted.

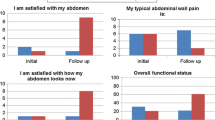

Patient satisfaction with the surgery and with cosmetic results was recorded on a 10-point Likert-type scale (1 = least satisfied, 10 = most satisfied). Chronic abdominal pain was a factor reported by the patient based on subjective experience. Postoperative pain scores were recorded as the level of worst abdominal pain experienced on a 10-point Likert-type scale (1 = least pain, 10 = most pain). Patient functional status was assessed from a series of 13 questions from the Activities Assessment Scale (AAS), where scores were converted to a 100-point scale (1 = worst functional status, 100 = best functional status) [31].

Secondary outcomes evaluated include recurrence, surgical site infection (SSI), seroma, and eventration. Recurrence was determined by radiographic data, clinical examination at follow-up, or reoperation reports. Surgical site infection was defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established guidelines for superficial, deep, and organ/space infections [32]. Seromas were recorded if the patient had radiographic evidence of a fluid collection or clinical evidence of a seroma, as noted by physician notes taken during physical examination on admission or at follow-up. Eventrations were determined if the patient had a clinical bulge noted at follow-up or on a computed tomography (CT) scan, which was considered evidence of mesh protrusion beyond the anterior plane of the abdominal wall.

Statistical analysis

Patient-centered outcome data were divided accorded to those patients judged to have good outcomes versus those judged to have poor outcomes. Poor patient satisfaction was defined as any score <7 on the 10-point Likert scale. Chronic pain was rated as a categorical variable. Poor functional status was defined as any AAS score <70 on the 100-point Likert scale.

Patient characteristics were assessed using a Student’s t test, the χ2 test, or Fisher’s exact test depending on whether the variables were continuous or categorical. Ordinal variables such as postoperative pain scores were assessed with the Mann–Whitney U test. Any p value of 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Univariate logistic regression models were built to estimate the odds of patient satisfaction, chronic pain, and functional status when considering the effect of each variable separately.

Multivariate logistic regression models were built to assess the effect of a given predictor on the dependent variable (patient satisfaction, chronic pain, or functional status) while controlling for other predictors in the model. To identify the most significant predictors, a multivariate model was initially created including all variables with a p value <0.20 from the initial assessment of patient characteristics and was then reduced in a stepwise manner to identify the best fit according to the Akaike Information Criterion. Diagnostics of the multivariate logistic regression model were assessed, and validation was performed with a tenfold cross-validation. All statistical analysis was performed on the statistical software R [33–35].

Results

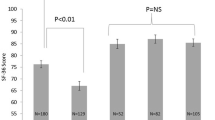

Of 201 patients evaluated, 122 patients had quality of life data on follow-up (Fig. 1). Ninety-one (74.5 %) patients were satisfied with their LVHR (patient satisfaction score ≥ 7), 101 (83.5 %) patients had no chronic abdominal pain following their LVHR, and 90 (73.8 %) patients had good functional status following their LVHR (AAS score ≥ 70).

Patient satisfaction results are shown in Table 1. On univariate analysis, female gender, mesh type, permanent transfascial sutures, and transcutaneous closure of central defects (TCCD) were associated with improved patient satisfaction. Patients with SSI, urinary tract infection, complication, readmission, recurrence, eventration, poor cosmetic satisfaction, chronic pain, or poor functional status had decreased overall satisfaction.

Comparative results of patients with and without chronic pain are shown in Table 2. On univariate analysis, black ethnicity, increased hernia size, incisional hernias, mesh type, recurrence, poor patient satisfaction, poor cosmetic satisfaction, and decreased functional status were associated with chronic pain.

Functional status outcomes are shown in Table 3. Older patients, patients with higher ASA score, mesh type, and failure to close the central defect (TCCD) were all associated with decreased functional status following LVHR. Patients who had any complication, recurrence, eventration, decreased satisfaction, or elevated late pain scores also had poorer function.

On multivariate analysis, low cosmetic satisfaction scores, eventration, and chronic pain were associated with decreased patient satisfaction (Table 4). Incisional hernias, eventration, and hernia recurrence were associated with chronic pain, along with mesh type used and Caucasian race (Table 4). Mesh type, alcohol abuse, chronic pain, and older age were associated with decreased functional status (Table 4).

Conclusions

In this study, we noted one fourth of patients were dissatisfied following their LVHR due to chronic pain and poor functional status, among other factors. These quality of life factors are interrelated. Chronic abdominal pain was associated with decreased patient satisfaction and poor function. In addition, continued bulging following LVHR due to eventration or recurrence was associated with decreased patient satisfaction and chronic pain.

Patient satisfaction with VHR has been reported to range from 75 to 88.4 % (Table 5) [25, 27]. Our study is consistent with these results. Unlike other studies, however, we noted that patient satisfaction with VHR is associated with satisfaction in abdomen appearance following repair, along with chronic pain. Patient dissatisfaction increased tenfold due to continued bulging although the repair was successful when measured by traditional surgical standards. Cosmetic factors had the strongest effect on patient satisfaction.

Surprisingly, factors such as hernia recurrence, SSI, or complications did not contribute to patient satisfaction on the multivariate analysis. This may be because many of the complications were early postoperative events and long-term recall may have attenuated their effect. Bulging or eventration had a greater effect on patient satisfaction than true hernia recurrence.

Prevalence of chronic pain following VHR ranges from 7 to 41 % (Table 5) [23, 25–27, 29]. Prior studies have associated chronic cough, recurrence, patient satisfaction/quality of life, and open repair with chronic pain [23, 25, 28, 29]. In our study we noted that incisional hernias were associated with chronic pain. This is to be expected, as these hernias tend to be larger and more complicated than primary hernias, such as umbilical or epigastric hernias. Consistent with other studies, we noted that recurrence was related to chronic pain [25]; however, we also found that eventration was associated with chronic pain. This may be because larger hernias (i.e., incisional hernias) are more likely to bulge with LVHR.

Additionally, we noted that mesh type (specifically polypropylene and polytetrafluoroethylene) was associated with increased rates of chronic pain. While many studies have demonstrated that low-density (i.e., misnomer “light weight mesh”) meshes are associated with improved patient satisfaction in groin hernias [36], other studies have also suggested that low-density meshes are associated with increased hernia recurrence, particularly with ventral hernias [24]. The effect and role of low-density meshes remains to be elucidated with ventral hernias, particularly incisional hernias.

Our analysis suggests that Caucasian patients may have an increased incidence of chronic pain. This may be due to the relative homogeneity of our study population. Alternatively, without preoperative chronic pain scores, this ethnic difference may simply be a manifestation of preoperative differences.

Few studies have evaluated functional status, instead focusing on quality of life (Table 5) [24, 25, 27–30]. The SF-36 questionnaire is the most common method of evaluating patient quality of life in VHR studies. In prior research, recurrence, chronic pain, and laparoscopic repair improved patient quality of life.

In our study, we opted to focus on functional status with the Activities Assessment Scale [32]. We noted that baseline characteristics such as older age and alcohol abuse were associated with diminished function. Our model also suggested that chronic pain and mesh type affected patient function. Many recent studies have suggested that low-density meshes are associated with improved patient function [24]. However, similar to chronic pain, low-density meshes resulted in poorer function in our study, possibly because of increased bulging or hernia recurrence that other studies have associated with low-density meshes.

Our study has several limitations. First, its retrospective nature introduces a number of biases into the results. For example, while we corrected for surgeon, several other variables could affect our results: variation in operative technique, postoperative management, and bedside manner. Second, patient-centered outcomes were only recorded for 61 % of our cohort overall. Patients who died or patients who were lost to follow-up may have contributed to non-responder bias. However, compared to other studies, we had robust follow-up. Third, without baseline or preoperative patient-centered outcomes, it can be difficult to gauge whether lower quality of life measures were due to preoperative factors as opposed to operative factors [37]. While we took into account baseline information, none can quite capture preoperative poor functional status or preoperative chronic pain [37]. Finally, as this study included patients from a Veteran’s Affairs Medical Center, the applicability of our results to younger, healthier, or more female populations should be approached with caution.

In conclusion, our study suggests that patient satisfaction, chronic pain, and functional status are all interrelated. Patient satisfaction is affected largely by cosmetic outcomes, though chronic pain does influence perception. Chronic pain is associated with incisional hernias, recurrence, and eventration. Mesh type and ethnicity may also play a role. Functional status is affected by baseline characteristics such as age and alcohol abuse; however, chronic pain and mesh type used may affect function as well. While standard outcomes affect patient-reported outcomes, factors most important to patients may differ from those most important to surgeons. In future studies, patient-reported outcomes should receive equal focus to that on more traditional outcomes.

References

Poulose BK, Shelton J, Phillips S et al (2011) Epidemiology and cost of ventral hernia repair: making the case for hernia research. Hernia 16:179–183

Mudge M, Hughes LE (1985) Incisional hernia: a 10 year prospective study of incidence and attitudes. Br J Surg 72:70–71

Hesselink VJ, Luijendijk RW, de Wilt JH et al (1993) An evaluation of risk factors in incisional hernia recurrence. Surg Gynecol Obstet 176:228–234

Luijendijk RW, Hop WC, van den Tol MP et al (2000) A comparison of suture repair with mesh repair for incisional hernia. N Engl J Med 343:392–398

Burger JW, Luijendijk RW, Hop WC et al (2004) Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of suture versus mesh repair of incisional hernia. Ann Surg 240:578–585

Fitzgibbons RJ Jr, Giobbie-Hurder A, Gibbs JO et al (2006) Watchful waiting vs repair of inguinal hernia in minimally symptomatic men: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 295:285–292

Itani KM, Hur K, Kim LT et al (2010) Comparison of laparoscopic and open repair with mesh for the treatment of ventral incisional hernia: a randomized trial. Arch Surg 145:322–328

Kurmann A, Visth E, Candinas D et al (2011) Long-term follow-up of open and laparoscopic repair of large incisional hernias. World J Surg 35:297–301. doi:10.1007/s00268-010-0874-9

Hawn MT, Snyder CW, Graham LA et al (2010) Long-term follow-up of technical outcomes for incisional hernia repair. J Am Coll Surg 210:648–655

Asencio F, Aguiló J, Peiró S et al (2009) Open randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open incisional hernia repair. Surg Endosc 23:1441–1448

Pring CM, Tran V, O’Rourke N et al (2008) Laparoscopic versus open ventral hernia repair: a randomized controlled trial. ANZ J Surg 78:903–906

Olmi S, Scaini A, Cesana GC et al (2007) Laparoscopic versus open incisional hernia repair: an open randomized controlled study. Surg Endosc 21:555–559

Barbaros U, Asoglu O, Seven R et al (2007) The comparison of laparoscopic and open ventral hernia repairs: a prospective randomized study. Hernia 11:51–56

Misra MC, Bansal VK, Kulkarni MP et al (2006) Comparison of laparoscopic and open repair of incisional and primary ventral hernia: results of a prospective randomized study. Surg Endosc 20:1839–1845

Carbajo MA, del Olmo JC, Blanco JI et al (2000) Laparoscopic treatment of ventral abdominal wall hernias: preliminary results in 100 patients. JSLS 4:141–145

Tse GH, Stutchfield BM, Duckworth AD et al (2010) Pseudo-recurrence following laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair. Hernia 14:583–587

Bencini L, Sanchez LJ, Bernini M et al (2009) Predictors of recurrence after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 19:128–132

Franklin ME Jr, Gonzalez JJ Jr, Glass JL et al (2004) Laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair: an 11-year experience. Hernia 8:23–27

Heniford BT, Park A, Ramshaw BJ et al (2003) Laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias: nine years’ experience with 850 consecutive hernias. Ann Surg 238:391–399

Carbajo MA, del Olmo JC, Blanco JI et al (2003) Laparoscopic approach to incisional hernia. Surg Endosc 17:118–122

Rosen M, Brody F, Ponsky J et al (2003) Recurrence after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Surg Endosc 17:123–128

LeBlanc KA, Whitaker JM, Bellanger DE et al (2003) Laparoscopic incisional and ventral hernioplasty: lessons learned from 200 patients. Hernia 7:118–124

Gronnier C, Wattier JM, Favre H et al (2012) Risk factors for chronic pain after open ventral hernia repair by underlay mesh placement. World J Surg 36:1548–1554. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1523-2

Ladurner R, Chiapponi C, Linhuber Q et al (2011) Long-term outcome and quality of life after open incisional hernia repair—light versus heavy weight meshes. BMC Surg 11:25

Snyder CW, Graham LA, Vick CC et al (2011) Patient satisfaction, chronic pain, and quality of life after elective incisional hernia repair: effects of recurrence and repair technique. Hernia 15:123–129

Wassenaar E, Schoenmaeckers E, Raymakers J et al (2010) Mesh-fixation method and pain and quality of life after laparoscopic ventral or incisional hernia repair: a randomized trial of three fixation techniques. Surg Endosc 24:1296–1302

Poelman M, Schellekens JF, Langenhorst BLAM et al (2010) Health-related quality of life in patients treated for incisional hernia with onlay technique. Hernia 14:237–242

Eriksen JR, Poornoroozy P, Jorgensen LN et al (2009) Pain, quality of life, and recovery after laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Hernia 13:13–21

Uranues S, Salehi B, Bergamaschi R (2008) Adverse events, quality of life, and recurrence rates after laparoscopic adhesiolysis and recurrent incisional hernia mesh repair in patients with previous failed repairs. J Am Coll Surg 207:663–669

Hope WW, Lincourt AE, Newcomb WL et al (2007) Comparing quality-of-life outcomes in symptomatic patients undergoing laparoscopic or open ventral hernia repair. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 18:567–571

McCarthy M Jr, Jonasson O, Chang CH et al (2005) Assessment of patient functional status after surgery. J Am Coll Surg 201:171–178

http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/pscManual/9pscSSIcurrent.pdf. Accessed 18 Nov 2011

Agresti A (2002) Categorical data analysis, 2nd edn. John Wiley, Hoboken

Kutner MH, Natchtsheim CJ, Neter J et al (2005) Applied linear statistical models, 5th edn. McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York

R Development Core Team (2012) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0. http://www.R-project.org/

Sajid MS, Leaver C, Baig MK et al (2012) Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of lightweight versus heavyweight mesh in open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 99:29–37

Albright EL, Davenport DL, Roth JS (2012) Preoperative functional health status impacts outcomes after ventral hernia repair. Am Surg 78:230–234

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, M.K., Clapp, M., Li, L.T. et al. Patient Satisfaction, Chronic Pain, and Functional Status following Laparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repair. World J Surg 37, 530–537 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-012-1873-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-012-1873-9